Saint Pierre and Miquelon

Saint Pierre And Miquelon Tourism Promotion

Saint Pierre and Miquelon (French: Collectivité territoriale de Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, French pronunciation: [sɛ̃.pjɛʁ.e.mi.klɔ̃]) is a self-governing territorial overseas collectivity of France, situated in the northwestern Atlantic Ocean near Canada. It is the only remnant of the former colonial empire of New France that remains under French control.

The islands are situated at the entrance of Fortune Bay, which extends into the southern coast of Newfoundland, near the Grand Banks. They are 3,819 kilometres (2,373 mi) from Brest, the nearest point in Metropolitan France, but just 20 kilometres (12 mi) off the Burin Peninsula of Newfoundland, Canada.

Etymology

Motto: “A Mare Labor” “From the Sea, Work”

Motto: “A Mare Labor” “From the Sea, Work”

Saint-Pierre is French for Saint Peter, who is a patron saint of fishermen.

The present name of Miquelon was first noted in the form of “Micquelle” in the Spanish sailor Martin de Hoyarçabal‘s navigational pilot for Newfoundland. It has been claimed that the name “Miquelon” is a Basque form of Michael, Mikel and Mikels are usually named Mikelon in the Basque Country. Therefore from Mikelon it may have been written in the French way with a “q” instead of a “k” It appears that this is a very common form in that language. Though the Basque Country is divided between Spain and France, most Basques live on the southern side of the border and speak Spanish, and Miquelon may have been influenced by the Spanish name Miguelón, an augmentative form of Miguel meaning “big Michael”. The adjoining island’s name of “Langlade” is said to be an adaptation of “l’île à l’Anglais” (Englishman’s Island).

History of Saint Pierre and Miquelon

Saint-Pierre aerial photo, 2013. Saint-Pierre Airport is at lower right. Original photo has extensive annotations.

Saint-Pierre aerial photo, 2013. Saint-Pierre Airport is at lower right. Original photo has extensive annotations.

Artifacts belonging to indigenous peoples have been found on Saint-Pierre. However, there was no aboriginal population on the island when the first European arrived.

The first European discovery of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon was on 21 October 1520, by the Portuguese João Álvares Fagundes, who bestowed on them their original name of “Islands of the 11,000 Virgins”, as the day marked the feast day of St. Ursula and her virgin companions. They were made a French possession in 1536 by Jacques Cartier on behalf of the King of France. Though already frequented by Mi’kmaq people and Basque and Breton fishermen, the islands were not permanently settled until the end of the 17th century: four permanent inhabitants were counted in 1670, and 22 in 1691.

In 1670, during Jean Talon‘s tenure as Intendant of New France, a French officer annexed the islands when he found a dozen French fishermen camped there. English ships soon began to harass the French, pillaging their camps and ships. By the early 1700’s, the islands were again uninhabited, and were ceded to the British by the Treaty of Utrecht which ended the War of the Spanish Succession in 1713.

French fishermen occasionally still visited the region, although they preferred the French Shore of Newfoundland, richer in fish and with greater possibilities for provisioning and repairs compared to these smaller islands. Under the terms of the 1763 Treaty of Paris, which put an end to the Seven Years’ War, France ceded all its North American possessions, but Saint-Pierre and Miquelon were returned to France. France also maintained fishing rights on the coasts of Newfoundland. After the long interlude of British occupation from 1714 to 1763, the islands knew little peace, but witnessed a significant rise in business and population, as they were now the last French territory in North America.

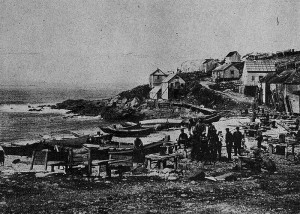

St Pierre, Le Quai La Roncière, 1887

St Pierre, Le Quai La Roncière, 1887

Britain invaded and razed the colony in 1778, during the American revolutionary war, and the entire population of 2,000 was sent back to France. By the 1780’s, about 1,000 or 1,500 people lived on the islands, their numbers doubling during the fishing season. The French Revolutionary Wars affected the archipelago dramatically: in 1793, the British landed in Saint-Pierre and, the following year, expelled the French population, and tried to install British settlers. The British colony was in turn sacked by French troops in 1796. The Treaty of Amiens of 1802 returned the islands to France, but Britain reoccupied them when hostilities recommenced the next year.

The 1814 Treaty of Paris gave them back to France, though Britain occupied them yet again during the Hundred Days War. France then reclaimed the by then uninhabited islands in which all structures and buildings had been destroyed or fallen into disrepair. The islands were resettled in 1816. The settlers were mostly Basques, Bretons and Normans, who were joined by various other elements, particularly from the nearby island of Newfoundland. Only around the middle of the century did increased fishing bring a certain prosperity to the little colony.

Modern History

During the early 1910s, the colony suffered severely as a result of unprofitable fisheries, and large numbers of its people emigrated to Nova Scotia and Quebec. The draft imposed on all male inhabitants of conscript age after the beginning of World War I crippled the fisheries, which could not be processed by the older people and the women and children. About 400 men from the colony served in the French military during World War I, 25% of whom died. The increase in the adoption of steam trawlers in the fisheries also contributed to the reduction in employment opportunities.

Smuggling had always been an important economic activity in the islands, but it became especially prominent in the 1920s with the institution of prohibition in the United States. In 1931, the archipelago was reported to have imported 1,815,271 U.S. gallons (1,511,529 imperial gallons; 6,871,550 litres) of whisky from Canada in 12 months, most of it to be smuggled into the United States. The end of prohibition in 1933 plunged the islands into economic depression.

After the fall of France during World War II, most of the war veterans and sailors in the colony supported the Free French of General Charles de Gaulle. The administrator of the colony, Gilbert de Bournat, sided with the Vichy regime. De Gaulle decided to seize the archipelago, over the opposition of the United States. The general covertly gave Admiral Émile Muselier the order to proceed, resulting in the successful Free French coup de main on Christmas Day 1941. The United States Department of State and Cordell Hull in particular were infuriated by the result. The incident ultimately served to focus the American public opinion on the ambivalence of the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt in its dealings with Vichy, and also led to a lasting distrust between De Gaulle and Roosevelt.

In a quick plebiscite the next day, the population endorsed the takeover, and the resounding vote in favour of Free France led Muselier to appoint Lieutenant Alain Savary as governor. After the approval of the 1958 French constitutional referendum, the islands were given the options of becoming fully integrated with France, becoming a self-governing state within the French Community, or preserving the status of overseas territory; it decided to remain a territory.