Pennsylvania Station & Grand Central (New York City)

History of the original Penn Station in New York City

The original Pennsylvania Station in New York City, built in 1910, was

an American classic that defined the city. Sadly, it was torn down in 1963.

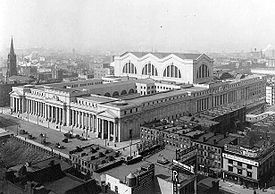

View from the northeast, c. 1911. The structure stood out among the other buildings in the area. Most of the buildings in the scene are no longer standing.

View from the northeast, c. 1911. The structure stood out among the other buildings in the area. Most of the buildings in the scene are no longer standing.

Pennsylvania Station is named for the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR), its builder and original tenant, and shares its name with several stations in other cities. The current facility is the substantially remodeled underground remnant of a much grander structure designed by McKim, Mead, and White and completed in 1910. The original Pennsylvania Station was considered a masterpiece of the Beaux-Arts style and one of the architectural jewels of New York City. Demolition of the original head house and train shed began in 1963. The Pennsylvania Plaza complex, including the fourth and current Madison Square Garden, was completed in 1968.

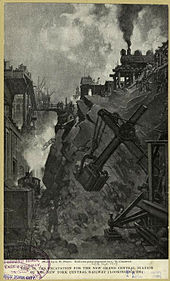

Planning and construction – Main article: New York Tunnel Extension

Until the early 20th century, the PRR’s rail network terminated on the western side of theHudson River (once known locally as the North River) at Exchange Place in Jersey City, New Jersey. Manhattan-bound passengers boarded ferries to cross the Hudson River for the final stretch of their journey. The rival New York Central Railroad‘s line ran down Manhattan from the north under Park Avenue and terminated at Grand Central Terminal at 42nd St.

Until the early 20th century, the PRR’s rail network terminated on the western side of theHudson River (once known locally as the North River) at Exchange Place in Jersey City, New Jersey. Manhattan-bound passengers boarded ferries to cross the Hudson River for the final stretch of their journey. The rival New York Central Railroad‘s line ran down Manhattan from the north under Park Avenue and terminated at Grand Central Terminal at 42nd St.

The Pennsylvania Railroad considered building a rail bridge across the Hudson, but the state required such a bridge to be a joint project with other New Jersey railroads, who were not interested. The alternative was to tunnel under the river, but steam locomotives could not use such a tunnel and in any case the New York State Legislaturehad prohibited steam locomotives in Manhattan after July 1, 1908. The development of the electric locomotive at the turn of the 20th century made a tunnel feasible. On December 12, 1901 PRR president Alexander Cassatt announced the railroad’s plan to enter New York City by tunneling under the Hudson and building a grand station on the West Side of Manhattan south of 34th Street.

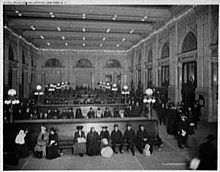

The concourse and steps down to the tracks

Beginning in June 1903 the North River Tunnels, two single-track tunnels, were bored from the west under the Hudson River and four single-track tunnels were bored from the east under the East River. This second set of tunnels linked the new station to Queens and the Long Island Rail Road, which came under PRR control (see East River Tunnels), and Sunnyside Yard in Queens, where trains would be maintained and assembled. Electrification was initially 600 volts DC–third rail, later changed to 11,000 volts AC–overheadcatenary, when electrification of PRR’s mainline was eventually extended to Washington, D. C. in the early 1930’s.

The tunnel technology was so innovative that in 1907 the PRR shipped an actual 23-foot (7.0 m) diameter section of the new East River Tunnels to the Jamestown Exposition in Norfolk, Virginia, to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the nearby founding of the colony at Jamestown. The same tube, with an inscription indicating that it had been displayed at the Exposition, was later installed under water and remains in use today. Construction was completed on the Hudson River tunnels on October 9, 1906, and on the East River tunnels March 18, 1908. Meanwhile, ground was broken for Pennsylvania Station on May 1, 1904. By the time of its completion and the inauguration of regular through train service on Sunday, November 27, 1910, the total project cost to the Pennsylvania Railroad for the station and associated tunnels was $114 million (approximately $2.7 billion in 2011 dollars), according to an Interstate Commerce Commission report.

The tunnel technology was so innovative that in 1907 the PRR shipped an actual 23-foot (7.0 m) diameter section of the new East River Tunnels to the Jamestown Exposition in Norfolk, Virginia, to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the nearby founding of the colony at Jamestown. The same tube, with an inscription indicating that it had been displayed at the Exposition, was later installed under water and remains in use today. Construction was completed on the Hudson River tunnels on October 9, 1906, and on the East River tunnels March 18, 1908. Meanwhile, ground was broken for Pennsylvania Station on May 1, 1904. By the time of its completion and the inauguration of regular through train service on Sunday, November 27, 1910, the total project cost to the Pennsylvania Railroad for the station and associated tunnels was $114 million (approximately $2.7 billion in 2011 dollars), according to an Interstate Commerce Commission report.

Occupying two city blocks from Seventh Avenue to Eighth Avenue and from 31st to 33rd Streets, the Pennsylvania Station building was 784 by 430 feet, covering an area of 8 acres (3.2 ha). It was one of the first rail terminals to separate arriving from departing passengers on two concourses.

The original structure was made of pink granite and marked by an imposing, sober colonnade of Roman unfluted version of classical Greek Doric columns. The colonnades embodied the sophisticated integration of multiple functions and circulation of people and goods. McKim, Mead & White‘s Pennsylvania Station combined glass-and-steel train sheds and a magnificently proportioned concourse with a breathtaking monumental entrance to New York City. From the street twin carriageways, modelled after Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate, led to the two railroads that the building served, the Pennsylvania and the Long Island Rail Road. The main waiting room, inspired by the Roman Baths of Caracalla, approximated the scale of St. Peter’s nave in Rome, expressed here in a steel framework clad in plaster that imitated the lower wall portions of travertine. 150 feet high, it was the largest indoor space in New York City and one of the largest public spaces in the world. The Baltimore Sun said in April, 2007 the station was “as grand a corporate statement in stone, glass and sculpture as one could imagine.” Historian Jill Jonnes called the original edifice a “great Doric temple to transportation.”

During half a century of operation under Pennsylvania Railroad (1910–1963) scores of intercity passenger trains arrived and departed daily to Chicago and St. Louis on “Pennsy” rails and beyond on connecting railroads to Miami and the west. Along with Long Island Rail Road trains Penn Station saw trains of the New Haven and the Lehigh Valley Railroads. During World War I and the early 1920’s rival Baltimore and Ohio Railroad passenger trains to Washington, Chicago, and St. Louis also used Penn Station, initially by order of the United States Railroad Administration, until the Pennsylvania Railroad terminated the B&O’s access in 1926. The station saw its heaviest use during World War II but by the late-1950’s intercity rail passenger volumes had declined dramatically with the coming of the Jet Age and the Interstate Highway System.

The Pennsylvania Railroad optioned the air rights of Penn Station in the 1950’s. The option called for the demolition of the head-house and train shed, to be replaced by an office complex and a new sports complex. The tracks of the station, perhaps fifty feet below street level, would remain untouched. Demolition began in October 1963. Plans for the new Penn Plaza and Madison Square Garden were announced in 1962. In exchange for the air-rights to Penn Station, the Pennsylvania Railroad would get a brand-new, air-conditioned, smaller station completely below street level at no cost, and a 25% stake in the new Madison Square Garden Complex.

The demolition of the head house—although considered by some to be justified as progressive at a time of declining rail passenger service—created international outrage. As dismantling of the structure began, The New York Times editorially lamented, “Until the first blow fell, no one was convinced that Penn Station really would be demolished, or that New York would permit this monumental act of vandalism against one of the largest and finest landmarks of its age of Roman elegance.”

Its destruction left a lasting wound in the architectural consciousness of the city. A famous photograph by Eddie Hausner of the ruined sculpture “Day” by Adolph Alexander Weinman in a landfill of the New Jersey Meadowlands struck a guilty chord. Pennsylvania Station’s demolition is considered the catalyst for the enactment of the city’s first architectural preservation statutes. The sculpture on the building, including the angel in the landfill, was created by Adolph Alexander Weinman. One of the sculpted clock surrounds, whose figures were modeled using model Audrey Munson, still survives as the Eagle Scout Memorial Fountain in Kansas City, Missouri. Another clock sculpture, “Night”, is install in the sculpture garden at the Brooklyn Museum, and 14 of the 22 original eagle ornaments still exist. Ottawa’s Union Station, built a year after Penn Station (in 1912), is another replica of the Baths of Caracalla. This train station’s departures hall now provides an idea of what the interior of Penn Station looked like (at half the scale). Chicago’s Union Station is similar as well.

Grand Central Turns 100: The Train Station that Transformed America

Grand Central Station turned 100 Years old on February 1st, 2013. The history of the largest transit station in the country has many secrets and discoveries that Sam Roberts, author of “Grand Central: How a Train Station Transformed America”, shares with Andrew Whitman on “Richard French Live.”

Grand Central Terminal – History

Looking out the north end of the Murray Hill Tunnel towards the station in 1880. Note the labels for the New York and Harlem andNew York and New Haven Railroads; theNew York Central and Hudson River was off to the left. The two larger portals on the right allowed some horse-drawn trains to continue further downtown.

Looking out the north end of the Murray Hill Tunnel towards the station in 1880. Note the labels for the New York and Harlem andNew York and New Haven Railroads; theNew York Central and Hudson River was off to the left. The two larger portals on the right allowed some horse-drawn trains to continue further downtown.

View of Grand Central around 1918.

View of Grand Central around 1918.

Three buildings serving essentially the same function have stood on this site. The original large and imposing scale was intended by the New York Central Railroad to enhance competition and compare favorably in the public eye with the archrival Pennsylvania Railroad and smaller lines.

Grand Central Terminal, New York

Grand Central Terminal, New York

Grand Central Depot brought the trains of the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad, the New York and Harlem Railroad, and the New York and New Haven Railroad together in one large station. The station was designed by John B. Snook and opened in October 1871. The original plan was for the Harlem Railroad to start using it on October 9, 1871 (moving from their 27th Street depot), the New Haven Railroad on October 16, and the Hudson River Railroad on October 23, with the staggering done to minimize confusion. However, the Hudson River Railroad did not move to it until November 1, which puts the other two dates in doubt.

The headhouse building containing passenger service areas and railroad offices was an “L” shape with a short leg running east-west on 42nd Street and a long leg running north-south on Vanderbilt Avenue. The train shed, north and east of the head house, had three innovations in U.S. practice: the platforms were elevated to the height of the cars, the roof was a balloon shed with a clear span over all of the tracks, and only passengers with tickets were allowed on the platforms (a rule enforced by ticket examiners). The Harlem, Hudson and New Haven trains were initially in side by side different stations, which created chaos in baggage transfer. The combined Grand Central Depot serviced all three railroads.

Grand Central Station

Between 1899 and 1900, the head house was essentially demolished. It was expanded from three to six stories with an entirely new facade, on plans by railroad architect Bradford Gilbert. The train shed was kept. The tracks that previously continued south of 42nd Street were removed and the train yard reconfigured in an effort to reduce congestion and turn-around time for trains. The reconstructed building was renamed Grand Central Station.

Grand Central Terminal

Between 1903 and 1913, the entire building was torn down in phases and replaced by the current Grand Central Terminal, which was designed by the architectural firms of Reed and Stem and Warren and Wetmore, who entered an agreement to act as the associated architects of Grand Central Terminal in February 1904. Reed & Stem were responsible for the overall design of the station, Warren and Wetmore added architectural details and the Beaux-Arts style. Charles Reed was appointed the chief executive for the collaboration between the two firms, and promptly appointed Alfred T. Fellheimer as head of the combined design team. This work was accompanied by the electrification of the three railroads using the station and the burial of the approach in the Park Avenue tunnel. The result of this was the creation of several blocks worth of prime real estate in Manhattan, which were then sold for a large sum of money. The new terminal opened on February 2, 1913.

Covering Park Avenue

To accommodate ever-growing rail traffic into the restricted Midtown area, William J. Wilgus, chief engineer of the New York Central Railroad took advantage of the recent electrification technology to propose a novel scheme: a bi-level station below ground.

Arriving trains would go underground under Park Avenue, and proceed to an upper-level incoming station if they were mainline trains, or to a lower-level platform if they were suburban trains. In addition, turning loops within the station itself obviated complicated switching moves to bring back the trains to the coach yards for servicing. Departing mainline trains reversed into upper-level platforms in the conventional way.

Burying electric trains underground brought an additional advantage to the railroads: the ability to sell above-ground air rights over the tracks and platforms for real-estate development. With time, prestigious apartment and office buildings were erected around Grand Central, which turned the area into the most desirable commercial office district in Manhattan.

The terminal also did away with bifurcating Park Avenue by introducing a “circumferential elevated driveway” that allowed Park Avenue traffic to traverse around the building and over 42nd Street without encumbering nearby streets. The building was also designed to eventually reconnect both segments of 43rd Street by going through the concourse if the City of New York demanded it.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pennsylvania_Station_(New_York_City)#History