National Museum of the American Indian

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Museum_of_the_American_Indian

500 Nations The Story of Indian Americans

All rights reserved to their respective owners. Upload made for educative purposes only.

The National Museum of the American Indian

The National Museum of the American Indian

Is part of the Smithsonian Institution and is dedicated to the life, languages, literature, history, and arts of the Native Americans of the Western Hemisphere. It has three facilities: the National Museum of the American Indian on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., which opened on September 21, 2004, on Fourth Street and Independence Avenue, Southwest; the George Gustav Heye Center, a permanent museum in New York City; and the Cultural Resources Center, a research and collections facility in Suitland, Maryland. The foundations for the present collections were first assembled in the former Museum of the American Indian in New York City, which was established in 1916.

History

Following controversy over Native leaders’ discovery that the Smithsonian Institution held more than 12,000-18,000 Indian remains, mostly in storage, the museum was established by an act of Congress in 1989, Public Law 101-185 – the National Museum of the American Indian Act, as “a living memorial to Native Americans and their traditions.” The creation of the museum brought together the collections of the Museum of the American Indian in New York City, founded in 1922, and the Smithsonian Institution. The National Museum of the American Indian Act also required that human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony be considered for repatriation to tribal communities, as well as objects acquired illegally. Since 1989 the Smithsonian has repatriated over 5,000 individual remains – about 1/3 of the total estimated human remains in its collection.

The Heye Foundation’s Museum of the American Indian opened to the public on Audubon Terrace in New York City in 1922. George Gustav Heye (1874–1957) traveled throughout North and South America collecting native objects. His collection was assembled over 54 years, beginning in 1903. He started the Museum of the American Indian and his Heye Foundation in 1916. The Heye collection became part of the Smithsonian in June 1990, and represents approximately 85% of the holdings of the NMAI. The Heye Collection was formerly displayed in the Audubon Terrace location, but had long been seeking a new building. The Museum of the American Indian considered options of merging with the Museum of Natural History, accepting an large donation from Ross Perot to be housed in a new museum building to be built in Dallas, or moving to the U.S. Customs House. The Heye Trust included a restriction requiring the collection to be displayed in New York City, and moving the collection to a Museum outside of New York aroused substantial opposition from New York politicians. The current arrangement represented a political compromise between those who wished to keep the Heye Collection in New York, and those who wanted it to be part of the new NMAI in Washington, DC. The NMAI was initially housed in lower Manhattan at the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House, which was refurbished for this purpose and remains an exhibition site; its building on the Mall in Washington, DC opened in 2005 .

Locations

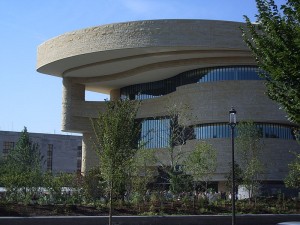

National Museum of the American Indian seen from the north

National Museum of the American Indian seen from the north

Interior view looking down toward the entrance

Interior view looking down toward the entrance

National Mall (Washington, D.C.)

The site on the National Mall opened in September 2004. Fifteen years in the making, it is the first national museum in the country dedicated exclusively to Native Americans. The five-story, 250,000-square-foot (23,000 m2), curvilinear building is clad in a golden-colored Kasota limestone designed to evoke natural rock formations shaped by wind and water over thousands of years. The museum is set in a 4.25 acres (17,200 m2)-site and is surrounded by simulated wetlands. The museum’s east-facing entrance, its prism window and its 120-foot (37 m) high space for contemporary Native performances are direct results of extensive consultations with Native peoples. Similar to the Heye Center in Lower Manhattan, the museum offers a range of exhibitions, film and video screenings, school group programs, public programs and living culture presentations throughout the year.

The museum’s architect and project designer is the Canadian Douglas Cardinal(Blackfoot); its design architects are GBQC Architects of Philadelphia and architect Johnpaul Jones (Cherokee/Choctaw). Disagreements during construction led to Cardinal’s being removed from the project, but the building retains his original design intent. His continued input enabled its completion.

The museum’s project architects are Jones & Jones Architects and Landscape Architects Ltd. of Seattle and SmithGroup of Washington, D.C., in association with Lou Weller (Caddo), the Native American Design Collaborative, and Polshek Partnership Architects of New York City; Ramona Sakiestewa (Hopi) and Donna House (Navajo/Oneida) also served as design consultants. The landscape architects are Jones & Jones Architects and Landscape Architects Ltd. of Seattle and EDAW, Inc., of Alexandria, Virginia.

In general, Native Americans have filled the leadership roles in the design and operation of the museum and have aimed at creating a different atmosphere and experience from museums of European and Euro-American culture. Donna E. House, the Navajo and Oneida botanist who supervised the landscaping, has said, “The landscape flows into the building, and the environment is who we are. We are the trees, we are the rocks, we are the water. And that had to be part of the museum.” This theme of organic flow is reflected by the interior of the museum, whose walls are mostly curving surfaces, with almost no sharp corners.

The Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House, site of the George Gustav Heye Center

The Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House, site of the George Gustav Heye Center

The Mitsitam Native Foods Cafe is divided into Native regional sections such as the Northern Woodlands, South America, the Northwest Coast, Meso-America, and the Great Plains. The only Native American groups not represented in the café are the south eastern tribes such as the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Cherokee and Seminole, many of which supported the United States throughout the tribes’ histories.

George Gustav Heye Center (New York City)

The Museum’s George Gustav Heye Center occupies two floors of the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House in Lower Manhattan. The Beaux Arts-style building, designed by architect Cass Gilbert, was completed in 1907. It is a designated National Historic Landmark and a New York City landmark. The center’s exhibition and public access areas total about 20,000 square feet (2,000 m2). The Heye Center offers a range of exhibitions, film and video screenings, school group programs and living culture presentations throughout the year.

Cultural Resources Center (Maryland)

In Suitland, Maryland, the National Museum of the American Indian operates the Cultural Resources Center, an enormous, nautilus-shaped building which houses the collection, a library, and the photo archives.

Collection

The National Museum of the American Indian is home to the collection of the former Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation. The collection includes more than 800,000 objects, as well as a photographic archive of 125,000 images. It is divided into the following areas: Amazon; Andes; Arctic/Subarctic; California/Great Basin; Contemporary Art; Mesoamerican/Caribbean;Northwest Coast; Patagonia; Plains/Plateau; Woodlands.

Representation of Crow horse regalia, ca. 1880’s with cradleboard on exhibit at NMAI

Representation of Crow horse regalia, ca. 1880’s with cradleboard on exhibit at NMAI

The collection, which became part of the Smithsonian in June 1990, was assembled by George Gustav Heye (1874–1957) during a 54-year period, beginning in 1903. He traveled throughout North and South America collecting Native objects. Heye used his collection to found New York’s Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation and directed it until his death in 1957. The Heye Foundation’s Museum of the American Indian opened to the public in New York City in 1922.

The collection is not subject to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. When the National Museum was created in 1989, a law governing repatriation was drafted specifically for the museum, the National Museum of the American Indian Act, upon which NAGPRA was modeled. In addition to repatriation, the museum dialogues with tribal communities regarding the appropriate curation of cultural heritage items. For example, the human remains vault is smudged once a week with tobacco, sage, sweetgrass, and cedar, and sacred Crow objects in the Plains vault are smudged with sage during the full moon. If the appropriate cultural tradition for curating an object is unknown, the Native staff uses their own cultural knowledge and customs to treat materials as respectfully as possible.

The museum has programs in which Native American scholars and artists can view NMAI’s collections to enhance their own research and artwork.

Reception

The National Museum of the American Indian has been criticized for various reasons due to its display of its exhibits. Two Washington Post reviews on the museum were hostile at the representation of the American Indian. Two writers, Fisher and Richard, expressed “irritation and frustration at the cognitive dissonance they experienced once inside the museum.” Fisher expected the displays that depicted the clash between foreign colonists and the native people. The exhibit lacked a trace of Indians’ evolution from centuries of life on this land, and gave little information as to the history of their survival. He concludes, “The museum feels like a trade show in which each group of Indians gets space to sell its founding myth and favorite anecdotes of survival. Each room is a sales booth of its own, separate, out of context, gathered in a museum that adds to the balkanization of a society that seems ever more ashamed of the unity and purpose that sustained it over two centuries.” Richards, who also had a similar assessment of the NMAI, begins his criticism by observing that he found the exhibits to be confusing and unclearly marked. To him, the exhibits were full with a mixture of “totem poles and T-shirts, headdresses and masks, toys and woven baskets, projectile points and gym shoes.” According to him, the items were presented in a hodgepodge that displayed history in an incoherent demonstration.

Edward Rothstein described the NMAI as an “identity museum” that “jettisons Western scholarship and tells its own story, leading one tribe to solemnly describe its earliest historical milestone: “Birds teach people to call for rain”; similarly, Diana Muir accused the curators of going “with verve and confidence to a place where subjective personal narrative is privileged above factual evidence, and the deliberate myth-making of an active national revival trumps scholarship.”

However, some other reviewers were pleased to see a focus on the living Native Americans as opposed to documenting their history. This reaction is in keeping with the museum’s main intentions, which are not to present a linear history of Native Americans. The council of the NMAI knows that the stories of Native American Indians are unfamiliar to most Americans; therefore, the intentions of using these artifacts were to allow their stories to teach the public about American Indians within the world today. By leaving these artifacts with no detailed labels, interpretation is open, giving the viewer the ability to construct a meaning for that artifact during that time. Many viewers saw that The National Museum of the American Indian explores self-identity of Native American Indians through how they dress, what they think, and how they see themselves within the world today.