Maryland

Maryland History

Timeline of Maryland: 1400’s – 1500’s

- (1498) John Cabot sailed eastern shore near (present day) Worcester County

- (1524) Giovanni da Verrazano passed mouth of Chesapeake Bay

- (1572) Chesapeake Bay explored by Pedro Menendez de Aviles, Spanish governor Florida

1600’s

- (1608) Capt. John Smith explored Chesapeake Bay

- (1631) William Claiborne established Kent Island trading post, farm settlement

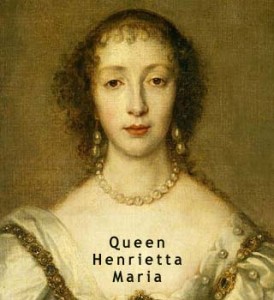

(1632) King Charles I of Great Britain granted Maryland Charter to Cecilius Calvert; colony named Maryland for Queen Henrietta Maria

(1632) King Charles I of Great Britain granted Maryland Charter to Cecilius Calvert; colony named Maryland for Queen Henrietta Maria- (1634) English settlers land at St. Clement’s Island, city of St. Mary founded

- (1634 – 1635) Meeting of First General Assembly held at St. Mary’s City

- (1645) Richard Ingle led rebellion against proprietary government (Ingle’s Rebellion)

- (1649) Virginia Puritans invited by Governor Stone to settle in Maryland; all Maryland Christians granted religious freedom by Act of Religious Toleration

- (1664) Law passed allowing slavery for life

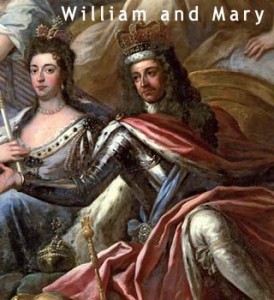

(1692) William and Mary declared Maryland to be royal colony; Sir Lionel Copley appointed governor

(1692) William and Mary declared Maryland to be royal colony; Sir Lionel Copley appointed governor- (1695) Annapolis became capital of Maryland

1700’s

- (1729) Baltimore founded

- (1744) Six Nations Chiefs relinquished all claims to Indian land in colony; Assembly purchased final Indian land claims

- (1750) First export trade of flour shipped to Irelandfrom Baltimore

- (1763 – 1767) Charles Mason, Jeremiah Dixon surveyed boundary line with Pennsylvania; Mason-Dixon line established as Maryland’s northern boundary

- (1765) Opposition to Stamp Act occurred at Frederick

- (1766) Sons of Liberty organized

- (1769) Non-importation policy of British goods established by Maryland merchants

- (1774) Mob burned Peggy Stewart ship loaded with tea in Annapolis harbor; Maryland chose delegates to Continental Congress

- (1776) Declaration of Independence adopted, four Marylanders signed; Maryland Convention declared independence from Great Britain; Maryland soldiers fought at Battle of Long Island; Maryland’s Declaration of Rights adopted; First State Constitution adopted

- (1777) State Consitution’s First General Assembly met at Annapolis; Thomas Johnson first governor

- (1783) Annapolis named nation’s capital

- (1784) Congress in Annapolis ratified Treaty of Paris, ended Revolutionary War

- (1788) Maryland became seventh U. S. state

- (1791) Maryland donated land for new capital in Washington, D.C.

- (1796) Law passed forbidding import of slaves for sale; permitted voluntary emancipation

- (1813) First steamboat, the Chesapeake, appeared in Chesapeake Bay; British raided Havre de Grace

- (1814) Francis Scott Key wrote “Star Spangled Banner” during British attack of Fort McHenry

- (1828) Construction began on nation’s first railroad – the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

- (1829) Chesapeake and Delaware Canal opened, linked Chesapeake Bay with Delaware River

- (1844) Samuel F. B. Morse demonstrated world’s first telegraph line, from Washington, D.C. to Baltimore

- (1845) U. S. Naval Academy founded at Annapolis

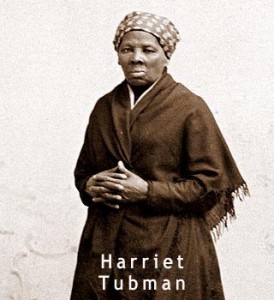

(1849) Harriet Tubman escaped slavery; began rescuing other slaves

(1849) Harriet Tubman escaped slavery; began rescuing other slaves- (1861) First bloodshed of Civil War occurred in Baltimore; federal troops occupied Annapolis; Union forces occupied Baltimore

- (1862) Confederate cavalry entered Cumberland; Battle of South Mountain – Union troops forced Confederates from Crampton’s and Turner’s Gaps; Confederates defeated at Antietam – most deadly battle of Civil War, 4,800 dead, 18,000 wounded

- (1863) Lee’s army passed through Maryland enroute to Gettysburg

- (1864) Hagerstown and Frederick held for ransom by Confederates; Maryland abolished slavery

- (1865) Marylander, John Wilkes Booth, assassinated President Abraham Lincoln

- (1876) Johns Hopkins University founded

- (1877) Baltimore and Ohil Railroad workers struck, demonstrated in Cumberland, rioted in Baltimore

- (1894) Baltimore Orioles won first baseball championship

The history of Maryland included only Native Americans until Europeans, starting with John Cabot in 1498, began exploring the area. The first settlements came in 1634 when the English arrived in significant numbers and created a permanent colony. In 1776, during the American Revolution, Maryland became a state in the United States. Although it was a slave state where many planters had Confederatesympathies, by 1860 nearly half the black population was already free, due mostly to manumissions after the American Revolution. Maryland remained in the Union during the American Civil War. Although small in size, the state has distinct socio-political-economic regions, including the city of Baltimore, Baltimore’s suburbs, the Washington suburbs, Western Maryland, and the Eastern Shore. Maryland has a democratic-type of state government.

The history of Maryland included only Native Americans until Europeans, starting with John Cabot in 1498, began exploring the area. The first settlements came in 1634 when the English arrived in significant numbers and created a permanent colony. In 1776, during the American Revolution, Maryland became a state in the United States. Although it was a slave state where many planters had Confederatesympathies, by 1860 nearly half the black population was already free, due mostly to manumissions after the American Revolution. Maryland remained in the Union during the American Civil War. Although small in size, the state has distinct socio-political-economic regions, including the city of Baltimore, Baltimore’s suburbs, the Washington suburbs, Western Maryland, and the Eastern Shore. Maryland has a democratic-type of state government.

Pre-colonial history

It appears that the first humans to arrive in the area that would become Maryland appeared around the 10th millennium BCE, about the time that the last ice age ended. They were hunter-gatherers organized into semi-nomadic bands. They adapted as the region’s environment changed, developing the spear for hunting as smaller animals, like deer, became more prevalent, and by about 1500 BCE oysters had become an important food resource in the region. With the increased variety of food sources, Native Americanvillages and settlements started appearing and their social structures increased in complexity. By about 1000 BCE pottery was being produced. With the eventual rise of agriculture more permanent Native-American villages were built. But even with the advent of farming, hunting and fishing were still important means of obtaining food. The bow and arrow were first used for hunting in the area around the year 800. They ate what they could kill, grow or catch in the rivers and other waterways. By 1000 BCE, there were about 8,000 Native Americans, all Algonquian-speaking, living in what is now the state, in 40 different villages. The following Piscataway tribes lived on the eastern bank of the Potomac, from south to north: Yaocomicoes, Chopticans,Nanjemoys, Potopacs, Mattawomans, Piscataways, Patuxents, and Nacotchtanks. The area the Nacotchtank lived in is now the District of Columbia. On the west bank of the Potomac river in what is now Virginia were the related tribes of the Patawomeck and the Doeg. Further west in the Appalachian Mountains, the Shawnee lived near Oldtown at a site abandoned around 1731. On the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake, from south to north, there were the Nanticoke tribes: Annemessex, Assateagues, Wicomicoes,Nanticokes, Chicacone, and, on the north bank of the Choptank River, the Choptanks. The Tockwogh tribe lived near the headwaters of the Chesapeake near what is now Delaware. When Europeans began to settle in Maryland in the early 17th century, the main tribes included the Nanticoke on the Eastern Shore. Early exposure to new European diseases brought widespread fatalities to the Native Americans, as they had no immunity to them. Communities were disrupted by such losses.

Early European exploration

In 1498 the first European explorers sailed along the Eastern Shore, off present-day Worcester Coun In 1524 Giovanni da Verrazzano, sailing under the French flag, passed the mouth of Chesapeake Bay. In 1608 John Smith entered the bay.

Colonial Maryland – See also: Province of Maryland

George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore, applied to Charles I for a royal charterfor what was to become the Province of Maryland. After Calvert died in April 1632, the charter for “Maryland Colony” (in Latin Terra Mariae) was granted to his son, Cecilius Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore, on June 20, 1632. Some historians viewed this as compensation for his father’s having been stripped of his title of Secretary of State in 1625 after announcing his Roman Catholicism. The colony was named in honor of Queen Henrietta Maria, the wife of KingCharles I. The specific name given in the charter was phrased Terra Mariae, anglice, Maryland. The English name was preferred due to undesired associations of Mariae with the Spanish Jesuit Juan de Mariana, linked to the Inquisition. As did other colonies, Maryland used the headright system to encourage people to bring in new settlers. Led by Leonard Calvert, Cecil Calvert’s younger brother, the first settlers departed from Cowes, on the Isle of Wight, on November 22, 1633 aboard two small ships, the Ark and the Dove. Their landing on March 25, 1634 at St. Clement’s Island in southern Maryland is commemorated by the state each year on that date as Maryland Day. This was the site of the first Catholic mass in the Colonies, with Father Andrew White leading the service. The first group of colonists consisted of 17 gentlemen and their wives, and about two hundred others, mostly indentured servants who could work off their passage. After purchasing land from the Yaocomico Indians and establishing the town of St. Mary’s, Leonard, per his brother’s instructions, attempted to govern the country under feudalistic precepts. Meeting resistance, in February 1635, he summoned a colonialassembly. In 1638, the Assembly forced him to govern according to the laws of England. The right to initiate legislation passed to the assembly. In 1638, Calvert seized a trading post in Kent Island established by the Virginian William Claiborne. In 1644, Claiborne led an uprising of Maryland Protestants. Calvert was forced to flee to Virginia, but he returned at the head of an armed force in 1646 and reasserted proprietarial rule.

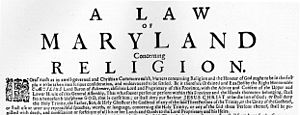

A large broadside of the Maryland Toleration Act Maryland soon became one of the few predominantly Catholic regions among the English colonies in North America. Maryland was also one of the key destinations where the government sent tens of thousands of English convicts punished by sentences of transportation. Such punishment persisted until the Revolutionary War. The Maryland Toleration Act, issued in 1649, was one of the first laws that explicitly defined tolerance of varieties of Christianity. It has been considered a precursor to the First Amendment. The founders designed the city plan of the colonial capital, St. Mary’s City, to reflect their world view. At the center of the city was the home of the mayor of St. Mary’s City. From that point, streets were laid out that created two triangles. Located at two points of the triangle extending to the west were the first Maryland state house and a jail. Extending to the north of the mayor’s home, the remaining two points of the second triangle were defined by a Catholic church and a school. The design of the city was a literal separation of church and state that reinforced the importance of religious freedom. The largest site of the original Maryland colony, St. Mary’s City was the seat of colonial government until 1708. Because Anglicanismhad become the official religion in Virginia, a band of Puritans in 1642 left for Maryland; they founded Providence (now called Annapolis). In 1650, the Puritans revolted against the proprietary government. They set up a new government prohibiting both Catholicism and Anglicanism. In March 1655, the 2nd Lord Baltimore sent an army under Governor William Stone to put down this revolt. Near Annapolis, his Roman Catholic army was decisively defeated by a Puritan army in the Battle of the Severn. The Puritan revolt lasted until 1658, when the Calvert family regained control and re-enacted the Toleration Act. The Puritan revolutionary government persecuted Maryland Catholics during its reign. Mobs burned down all the original Catholic churches of southern Maryland. In 1708, the seat of government was moved to Providence, renamed Annapolis in honor of Queen Anne. St. Mary’s City is now an archaeological site, with a small tourist center. Just as the city plan for St. Mary’s City reflected the ideals of the founders, the city plan of Annapolis reflected those in power at the turn of the 18th century. The plan of Annapolis extends from two circles at the center of the city – one including the State House and the other the Anglican St. Anne’s Church (now Episcopal). The plan reflected a stronger relationship between church and state, and a colonial government more closely aligned with the Protestant church. Based on an incorrect map, the original royal charter granted Maryland the Potomac River and territory northward to the fortieth parallel. This was found to be a problem, as the northern boundary would have put Philadelphia, the major city in Pennsylvania, within Maryland. The Calvert family, which controlled Maryland, and the Penn family, which controlled Pennsylvania, decided in 1750 to engage two surveyors, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon, to establish a boundary. They surveyed what became known as the Mason–Dixon Line, which became the boundary between the two colonies. The crests of the Penn family and of the Calvert family were put at the Mason–Dixon line to mark it. Later the Mason–Dixon line was used as a boundary between free and slave states under the Missouri Compromise of 1820.

A large broadside of the Maryland Toleration Act Maryland soon became one of the few predominantly Catholic regions among the English colonies in North America. Maryland was also one of the key destinations where the government sent tens of thousands of English convicts punished by sentences of transportation. Such punishment persisted until the Revolutionary War. The Maryland Toleration Act, issued in 1649, was one of the first laws that explicitly defined tolerance of varieties of Christianity. It has been considered a precursor to the First Amendment. The founders designed the city plan of the colonial capital, St. Mary’s City, to reflect their world view. At the center of the city was the home of the mayor of St. Mary’s City. From that point, streets were laid out that created two triangles. Located at two points of the triangle extending to the west were the first Maryland state house and a jail. Extending to the north of the mayor’s home, the remaining two points of the second triangle were defined by a Catholic church and a school. The design of the city was a literal separation of church and state that reinforced the importance of religious freedom. The largest site of the original Maryland colony, St. Mary’s City was the seat of colonial government until 1708. Because Anglicanismhad become the official religion in Virginia, a band of Puritans in 1642 left for Maryland; they founded Providence (now called Annapolis). In 1650, the Puritans revolted against the proprietary government. They set up a new government prohibiting both Catholicism and Anglicanism. In March 1655, the 2nd Lord Baltimore sent an army under Governor William Stone to put down this revolt. Near Annapolis, his Roman Catholic army was decisively defeated by a Puritan army in the Battle of the Severn. The Puritan revolt lasted until 1658, when the Calvert family regained control and re-enacted the Toleration Act. The Puritan revolutionary government persecuted Maryland Catholics during its reign. Mobs burned down all the original Catholic churches of southern Maryland. In 1708, the seat of government was moved to Providence, renamed Annapolis in honor of Queen Anne. St. Mary’s City is now an archaeological site, with a small tourist center. Just as the city plan for St. Mary’s City reflected the ideals of the founders, the city plan of Annapolis reflected those in power at the turn of the 18th century. The plan of Annapolis extends from two circles at the center of the city – one including the State House and the other the Anglican St. Anne’s Church (now Episcopal). The plan reflected a stronger relationship between church and state, and a colonial government more closely aligned with the Protestant church. Based on an incorrect map, the original royal charter granted Maryland the Potomac River and territory northward to the fortieth parallel. This was found to be a problem, as the northern boundary would have put Philadelphia, the major city in Pennsylvania, within Maryland. The Calvert family, which controlled Maryland, and the Penn family, which controlled Pennsylvania, decided in 1750 to engage two surveyors, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon, to establish a boundary. They surveyed what became known as the Mason–Dixon Line, which became the boundary between the two colonies. The crests of the Penn family and of the Calvert family were put at the Mason–Dixon line to mark it. Later the Mason–Dixon line was used as a boundary between free and slave states under the Missouri Compromise of 1820.

The Revolutionary period – Further information: History of the United States (1776-1789) Main article: History of Maryland in the American Revolution

Maryland did not at first favor independence from Great Britain and gave instructions to that effect to its delegates to the Continental Congress. During this initial phase of the Revolutionary period, Maryland was governed by the Assembly of Freemen, an assembly of the state’s counties. The first convention lasted four days, from June 22 to June 25, 1774. All sixteen counties then existing were represented by a total of 92 members; Matthew Tilghman was elected chairman.

Thomas Johnson, Maryland’s first elected governor under its 1776 Constitution The eighth session decided that the continuation of an ad-hoc government by the convention was not a good mechanism for all the concerns of the province. A more permanent and structured government was needed. So, on July 3, 1776, they resolved that a new convention be elected that would be responsible for drawing up their first state constitution, one that did not refer to parliament or the king, but would be a government “…of the people only.” After they set dates and prepared notices to the counties they adjourned. On August 1, all freemen with property elected delegates for the last convention. The ninth and last convention was also known as the Constitutional Convention of 1776. They drafted a constitution, and when they adjourned on November 11, they would not meet again. The conventions were replaced by the new state government which the Maryland Constitution of 1776 had established. Thomas Johnsonbecame the state’s first elected governor. On March 1, 1781, the Articles of Confederation took effect with Maryland’s ratification. The articles had initially been submitted to the states on November 17, 1777, but the ratification process dragged on for several years, stalled by an interstate quarrel over claims to uncolonized land in the west. Maryland was the last hold-out; it refused to ratify until Virginia and New York agreed to rescind their claims to lands in what became the Northwest Territory.

Thomas Johnson, Maryland’s first elected governor under its 1776 Constitution The eighth session decided that the continuation of an ad-hoc government by the convention was not a good mechanism for all the concerns of the province. A more permanent and structured government was needed. So, on July 3, 1776, they resolved that a new convention be elected that would be responsible for drawing up their first state constitution, one that did not refer to parliament or the king, but would be a government “…of the people only.” After they set dates and prepared notices to the counties they adjourned. On August 1, all freemen with property elected delegates for the last convention. The ninth and last convention was also known as the Constitutional Convention of 1776. They drafted a constitution, and when they adjourned on November 11, they would not meet again. The conventions were replaced by the new state government which the Maryland Constitution of 1776 had established. Thomas Johnsonbecame the state’s first elected governor. On March 1, 1781, the Articles of Confederation took effect with Maryland’s ratification. The articles had initially been submitted to the states on November 17, 1777, but the ratification process dragged on for several years, stalled by an interstate quarrel over claims to uncolonized land in the west. Maryland was the last hold-out; it refused to ratify until Virginia and New York agreed to rescind their claims to lands in what became the Northwest Territory.

Marylander John Hanson (circa 1765 to 1770) was the first person to serve a full term as President of the Continental Congress under the Articles of Confederation.

Marylander John Hanson (circa 1765 to 1770) was the first person to serve a full term as President of the Continental Congress under the Articles of Confederation.

No significant battles of the American Revolutionary War occurred in Maryland. However, this did not prevent the state’s soldiers from distinguishing themselves through their service. General George Washington was impressed with the Maryland regulars (the “Maryland Line“) who fought in the Continental Army and, according to one tradition, this led him to bestow the name “Old Line State” on Maryland. Today, the Old Line Stateis one of Maryland’s two official nicknames. The state also filled other roles during the war. For instance, the Continental Congress met briefly in Baltimore from December 20, 1776, through March 4, 1777. Furthermore, a Marylander, John Hanson, served as President of the Continental Congress from 1781 to 1782. Hanson was the first person to serve a full term as President of the Congress under the Articles of Confederation. From November 26, 1783, to June 3, 1784, Annapolis served as the United States capital, and the Confederation Congress met in the Maryland State House. (Annapolis was a candidate to become the new nation’s permanent capital before Washington, D.C. was built). It was in the old senate chamber that George Washington famously resigned his commission as commander in chief of the Continental Army on December 23, 1783. It was also there that the Treaty of Paris, which ended the Revolutionary War, was ratified by Congress on January 14, 1784.

Maryland, 1789–1849 – Further information: History of the United States (1789-1849)

Quasi-war with France

After the Revolution, the US Congress approved construction of six frigates to form a nucleus of what became the United States Navy. Of the first three commissioned, one was designated for construction in Baltimore’s shipyards and was named USS Constellation. Constellation became the first official US Navy ship put to sea. Almost immediately after getting underway, Constellation was ordered to the Caribbean to protect US interests against the French. Tensions had increased following the Haitian Revolution and independence in 1804, as European powers attempted to maintain control. During the Quasi-War, Constellation, under the command of Captain Thomas Truxtun, was forced into two major ship-to-ship naval battles involving the French ship L’Insurgente and the heavier frigate Vengeance. With its victories in both encounters, Constellation also achieved the first capture by an American vessel of an enemy ship (L’Insurgente). Its return to Baltimore was accompanied by joyous celebration and nationwide fame. TheConstellation’s incredible speed and power inspired the French to nickname her the “Yankee Racehorse”.

The War of 1812

During the War of 1812 the British conducted raids against cities along Chesapeake Bay, up to and including Havre de Grace. There were also two notable battles that occurred in the state. The first was the Battle of Bladensburg, which occurred on August 24, 1814 just outside the national capital, Washington, D.C. The militiamen defending the city were routed and retreated in confusion through the streets of the city. After overrunning the confused American defenders at Bladensburg, the British took Washington, D.C. They burned and looted major public buildings (see Burning of Washington), forcing President James Madison to flee to Brookeville, Maryland.

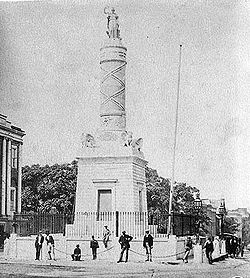

Battle of North Point Monument (dedicated 1815), ca. 1870–1875, which appears on both the flag and the seal of Baltimore, Maryland

Battle of North Point Monument (dedicated 1815), ca. 1870–1875, which appears on both the flag and the seal of Baltimore, Maryland

The British marched next to Baltimore, where they hoped to strike a knockout blow against the demoralized Americans. Baltimore was not only a busy port, but the British thought it harbored many of the privateers who were despoiling British ships. The city’s defenses were under the command of Major General Samuel Smith, an officer of Maryland militia and a United States senator. Baltimore had been well fortified with excellent supplies and some 15,000 troops. Maryland militia fought a determined delaying action at the Battle of North Point, during which a Maryland militia marksman shot and killed the British commander, general Robert Ross. The battle bought enough time for Baltimore’s defenses to be strengthened. After advancing to the edge of American defenses, the British halted their advance and withdrew. With the failure of the land advance, the sea battle became irrelevant and the British retreated. At Fort McHenry, some 1000 soldiers under the command of Major George Armistead awaited the British naval bombardment. Their defense was augmented by the sinking of a line of American merchant ships at the adjacent entrance to Baltimore Harbor in order to thwart passage of British ships. The attack began on the morning of September 13, as the British fleet of some nineteen ships began pounding the fort with rockets and mortar shells. After an initial exchange of fire, the British fleet withdrew just beyond the 1.5 miles (2.4 km) range of Fort McHenry’s cannons. For the next 25 hours, they bombarded the outmanned Americans. On the morning of September 14, an oversized American flag, which had been hastily sewn for this event, still flew over Fort McHenry. The British knew that victory had eluded them. The bombardment of the fort inspired Francis Scott Key, a native of Frederick, Maryland, to write “The Star-Spangled Banner” as witness to the assault. It later became the country’s national anthem.