Maine

Through Their Eyes

Bath Maine historical documentary produced by the Times Record in 1997.

Timeline of Maine: 1400’s – 1500’s

Timeline of Maine: 1400’s – 1500’s

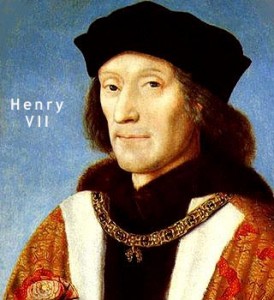

- (1497) Explorer John Cabot claimed land near Cape Breton for King Henry VII

- (1524) Explorer, Giovanni de Verranzano, first European to explore coast of Maine

- (1597) Portuguese navigator, Simon Ferdinando, sought treasure on coast of Maine

1600’s

- (1604) First European colony in Maine established at mouth of St. Croix River by French

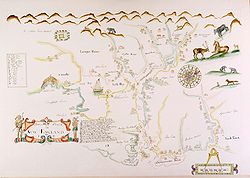

(1604 – 1605) Maine coastline and Penobscot River explored and mapped by French cartographer, Samuel del Champlain

(1604 – 1605) Maine coastline and Penobscot River explored and mapped by French cartographer, Samuel del Champlain- (1622) Sir Ferdinando Gorges, John Mason granted rights to lands of present day Maine, New Hampshire; Gorges named territory “Maine”

- (1623) First sawmill in America established near York

- (1652) Maine annexed as frontier territory by Massachusetts

- (1675) King Philip’s War began between English, French and Indians

- (1675 – 1763) Continuous conflict between North American forces

- (1761) First pile bridge built at York

- (1765) Mob seized quantity of tax stamps at Falmouth; attacked customs agents

- (1774) Group of men burned tea shipment at York

- (1775) First naval battle of Revolutionary War fought off coast of Machias; British warships shelled, bombed Falmouth; Benedict Arnold, band of revolutionaries marched through Maine, failed in attempt to capture British strongholds in Canada

- (1785) Falmouth Gazette established – Maine’s first newspaper

1800’s

- (1812) Bangor, other parts of Maine seized by British

- (1820) Maine became 23rd state; first state to give suffrage, school privileges to all

- (1832) State capital established in Augusta

- (1839) Governor Fairfield declared war on England due to boundary dispute between New Brunswick, northern Maine

- (1842) Webster-Ashburton Treaty settled Maine/New Brunswick border dispute

- (1851) Maine first state to outlaw sale of alcoholic beverages

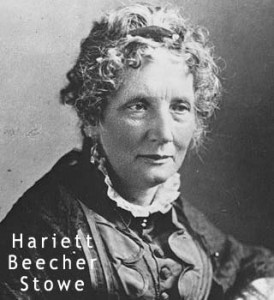

(1852) Harriet Beecher Stowe of Brunswick, wrote “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”

(1852) Harriet Beecher Stowe of Brunswick, wrote “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”- (1860) Maine native, Hannibal Hamlin, named Abraham Lincoln’s vice president

- (1863) Joshua Chamberlain, Maine native, defended Little Round Top against confederates at Battle of Gettysburg during Civil War

- (1866) Fire destroyed most of downtown Portland

- (1876) July 4 freak snowstorm struck Portland

- (1888) Maine native, Melville W. Fuller, became U. S. Supreme Court Chief Justice

The history of the area comprising the U.S. state of Maine spans thousands of years, measured from the earliest human settlement, or less than two hundred, measured from the advent of U.S. statehood in 1820. The present article will concentrate on the period of European contact and after.

The history of the area comprising the U.S. state of Maine spans thousands of years, measured from the earliest human settlement, or less than two hundred, measured from the advent of U.S. statehood in 1820. The present article will concentrate on the period of European contact and after.

The origin of the name Maine is unclear. One theory is it was named after the French province of Maine. Another is that it derives from a practical nautical term, “the main” or “Main Land”, “Meyne” or “Mainland”, which served to distinguish the bulk of the state from its numerous islands.

Pre-European history

The earliest culture known to have inhabited Maine, from roughly 3000 B.C. to 1000 B.C., were the Red Paint People, a maritime group known for elaborate burials using red ochre. They were followed by the Susquehanna culture, the first to use pottery.

By the time of European arrival, the inhabitants of Maine were Algonquian-speaking Wabanaki peoples, including the Abenaki,Passamaquoddy, and Penobscots.

Colonial period

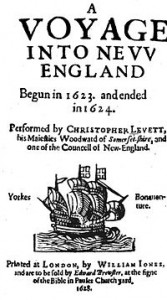

A Voyage into New England, written by Capt. Christopher Levett to spur interest in his Maine colony

A Voyage into New England, written by Capt. Christopher Levett to spur interest in his Maine colony

The first Europeans to explore the coast of Maine sailed under the command of the Portuguese explorer Estêvão Gomes, in service of the Spanish Empire, in 1525. They mapped the coastline (including the Penobscot River) but did not settle. The first European settlement in the area was made on St. Croix Island in 1604 by a French party that includedSamuel de Champlain. The French named the area Acadia. French and English settlers would contest central Maine until the 1750s (when the French were defeated in the French and Indian War). The French developed and maintained strong relations with the area’s Native American tribes through the medium of Catholic missionaries.

English colonists sponsored by the Plymouth Company attempted a settlement in Maine in 1607 (the Popham Colony at Phippsburg), but it was abandoned the following year. A French trading post was established at present-day Castine in 1613 by Claude de Saint-Étienne de la Tour, and may represent the first permanent European settlement in New England. The Plymouth Colony, established on the shores of Cape Cod Bay in 1620, set up a competing trading post at Penobscot Bay in the 1620s.

The territory between the Merrimack and Kennebec rivers was first called the Province of Maine in a 1622 land patent granted to Sir Ferdinando Gorges and John Mason. The two split the territory along the Piscataqua River in a 1629 pact that resulted in the Province of New Hampshire being formed by Mason in the south and New Somersetshire being created by Gorges to the north, in what is now southwestern Maine. The present Somerset County in Maine preserves this early nomenclature.

One of the first English attempts to settle the Maine coast was by Christopher Levett, an agent for Gorges and a member of the Plymouth Council for New England. After securing a royal grant for 6,000 acres (24 km2) of land on the site of present-day Portland, Maine, Levett built a stone house and left a group of men behind when he returned to England in 1623 to drum up support for his settlement, which he called “York” after the city of his birth in England. Originally called Machigonne by the local Abenaki, later settlers named it Falmouth and it is known today as Portland. Levett’s settlement, like the Popham Colony also failed, and the men Levett left behind were never heard from again. Levett did sail back across the Atlantic to meet with Massachusetts Bay Colony Governor John Winthrop at Salem in 1630, but died on the return voyage without ever returning to his settlement.

The New Somersetshire colony was small, and in 1639 Gorges received a second patent, from Charles I, covering the same territory as Gorges’ 1629 settlement with Mason. Gorges’ second effort resulted in the establishment of more settlements along the coast of southern Maine, and along the Piscataqua River, with a formal government under his distant relation, Thomas Gorges. A dispute about the bounds of another land grant led to the short-lived formation of Lygonia on territory that encompassed a large area of the Gorges grant. Both Gorges’ Province of Maine and Lygonia had been absorbed into the Massachusetts Bay Colony by 1658. The Massachusetts claim would be overturned in 1676, but Massachusetts again asserted control by purchasing the territorial claims of the Gorges heirs.

In 1669, the territory between the Kennebec and St. Croix rivers was granted by Charles II to his brother James, Duke of York. Under the terms of this grant, all the territory from the Saint Lawrence River to the Atlantic Ocean was constituted as Cornwall County, and was governed as part of the duke’s proprietary Province of New York. This grant, when combined with the territories claimed by Massachusetts (which it called York County), encompassed all of present-day Maine.

Copy of English map of Maine, c. 1670

Copy of English map of Maine, c. 1670

In 1686 James, now king, established the Dominion of New England. This political entity eventually combined all of the English-held territories from Delaware Bay to the St. Croix River. The dominion collapsed in 1689, and in 1692 the territory between the Piscataqua and the St. Croix became part of the new Province of Massachusetts Bay as Yorkshire, a name which survives in present day York County.

Colonial Wars

For the English, east of the Kennebec River was known in the 17th century as the Territory of Sagadahock, however, the French included this area as part of Acadia. It was dominated by tribes of the Wabanaki Confederacy, which supported Acadia. The only significant European presence was at Fort Pentagouet, the French trading post first established in 1613 as well as missionaries on Kennebec River and the Penobscot River. Fort Pentagouet was briefly the capital of Acadia (1670-1674) in an effort to protect the French claim to the territory. There were four wars before the region was finally taken by the English in Father Rale’s War.

In the first war, King Philips War, some of the tribes of the Wabanaki Confederacy participated and successfully prevented English settlements in their territory. During the next war, King William’s War, Baron St. Castin at Fort Pentagouet and French Jesuit missionary Sébastien Rale were notably active. Again, the Wabanaki Confederacy executed a successful campaign against the English settlers west of the Kennebec River. In 1696, the major defensive establishment in the territory, Fort William Henry at Pemaquid (present-day Bristol), was besieged by a French force. The territory was again on the front lines in Queen Anne’s War(1702–1713), with the Northeast Coast Campaign.

The next and final conflict over the New England/ Acadia border was Father Rale’s War. During the war, the Confederacy launched two campaigns against the British settlers west of the Kennebec (1723, 1724). Rale and numerous chiefs were killed by a New England force in 1724 at Norridgewock, which led to the collapse of French claims to Maine.

During King George’s War, members of the Wabanaki Confederacy led three campaigns against the British settlers in Maine (1745, 1746, 1747). During the final colonial war, the French and Indian War, members of the Confederacy again executed numerous raids into Maine from Acadia/ Nova Scotia. Acadian militia raided the British settlements of present-day Friendship, Maine and Thomaston, Maine.

After the defeat of the French colony of Acadia, the territory from the Penobscot River east fell under the nominal authority of the Province of Nova Scotia, and together with present day New Brunswick formed the Nova Scotia County of Sunbury, with its court of general sessions at Campobello Island.

In the late 18th century, several tracts of land in Maine, then part of Massachusetts, were sold off by lottery. Two tracts of 1,000,000 acres (4,000 km²), one in south-east Maine and another in the west, were bought by a wealthy Philadelphia banker, William Bingham. This land became known as the Bingham Purchase.

American Revolution

Maine was a center of Patriotism during the American Revolution, with less Loyalist activity than most colonies. Merchants operated 52 ships that served as privateers attacking British supply ships. Machias in particular was a center for privateering and Patriot activity. It was the site of an early naval engagement that resulted in the capture of a small Royal Navy vessel. Jonathan Eddy led a failed attempt to capture Fort Cumberland in Nova Scotia in 1776. In 1777 Eddy led the defense of Machias against a Royal Navy raid.

Captain Henry Mowat of the Royal Navy had charge of operations off the Maine coast during much the war. He dismantled Fort Pownall at the mouth of the Penobscot River and burned Falmouth in 1775. (present-day Portland). His reputation in Maine traditions is heartless and brutal, but historians note that he performed his duty well and in accordance with the ethics of the era.

New Ireland

In 1779 the British adopted a strategy to seize parts of Maine, especially around Penobscot Bay, and make it a new colony to be called “New Ireland”. The scheme was promoted by exiled Loyalists Dr. John Calef (1725–1812) and John Nutting (fl. 1775-85) and Englishman William Knox (1732–1810). It was intended to be a permanent colony for Loyalists and a base for military action during the war. The plan ultimately failed because of a lack of interest by the British government and the determination of the Americans to keep all of Maine.

In July 1779 British general Francis McLean captured Castine and built Fort George on the Bagaduce Peninsula on the eastern side of Penobscot Bay. The state of Massachusetts sent the Penobscot Expedition led by Massachusetts general Solomon Lovell and Continental Navy captain Dudley Saltonstall. The Americans failed to dislodge the British during a 21-day siege and were routed by the arrival of British reinforcements. The Royal Navy blocked an escape by sea so the Patriots burned their ships near present-day Bangor and walked home. Maine was unable to repel the British threat despite a reorganized defense and the imposition of martial law in selected areas. Some of the most easterly towns tried to become neutral.

After the peace was signed in 1783, the New Ireland proposal was abandoned. In 1784 the British split New Brunswick off from Nova Scotia and made it into the desired Loyalist colony, with deference to King and Church, and with republicanism suppressed. It was almost named “New Ireland”.

The Treaty of Paris that ended the war was ambiguous about the boundary between Maine and the neighboring British provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec. This would set the stage for further fighting in the nineteenth century.

War of 1812

During the War of 1812, Maine suffered from the effects of warfare more than most sections of New England. Early in the war there was some Canadian privateering action and Royal Navy harassment along the coast. In September 1813, the memorable combat off Pemaquid between HMS Boxer and USS Enterprise gained international attention. A noteable sidelight, both commanders – British Captain Samuel Blyth and American Lieutenant William Burrows were killed in the action. Authorities conducted an impressive joint funeral in Portland and the two officers were buried side-by-side in the Eastern Cememtery. But it wasn’t until 1814 that the district was invaded. The U.S.Army and the small U.S. Navy did little to defend Maine. The national administration assigned nominal resources to the region, concentrating its efforts in the west. The local militia generally proved inadequate to the task. However, in the last months of the war, large militia mobilizations discouraged enemy interventions at Wiscasset, Bath, and Portland. British army and naval forces from nearby Nova Scotia captured and occupied the eastern coast from Eastport to Castine, and plundered the Penobscot River towns of Hampden and Bangor (see Battle of Hampden). Legitimate commerce all along the Maine coast was largely stopped—a critical situation for a place so dependent on shipping. In its place an illicit smuggling trade with the British developed, especially at Castine and Eastport. Claims to “New Ireland” were finally dropped in the Treaty of Ghent, and Castine was evacuated, although Eastport remained under occupation until 1818. But Maine’s vulnerability to foreign invasion, and its lack of protection by Massachusetts, were important factors in the post-war momentum for statehood.

Maine Constitutional Convention and statehood

The Maine Constitution was unanimously approved by the 210 delegates to the Maine Constitutional Convention in October 1819. It was then ratified by Congress on March 4, 1820, as part of the Missouri Compromise, in which free northern states approved the statehood of Missouri as a slave state in exchange for the statehood of Maine as a free one. In this manner, northern representation remained in balance with southern pro-slavery influence in the Senate.

Maine gained its statehood from Massachusetts on March 15, 1820, with William King as the state’s first Governor. William D. Williamson became the first President of the Maine State Senate. When King resigned as governor in 1821, Williamson automatically succeeded him to become Maine’s second governor. That same year, however, he ran for and won a seat in the 17th United States Congress. Upon Williamson’s resignation, Speaker of the Maine House of Representatives Benjamin Ames became Maine’s third governor for approximately a month until Daniel Rose took office. Rose served only from January 2 to January 5, 1822, filling the unexpired term between the administrations of Ames and Albion K. Parris. Parris served as governor until January 3, 1827. Thus in less than two years after gaining statehood, Maine had five different governors.

The Aroostook War – Main article: Aroostook War

The still-lingering border dispute with British North America came to a head in 1839 when Maine Governor John Fairfield declared virtual war on lumbermen from New Brunswick cutting timber in lands claimed by Maine. Four regiments of the Maine militia were mustered in Bangor and marched to the border, but there was no fighting. The Aroostook War was an undeclared and bloodless conflict that was settled by diplomacy.

U.S. Secretary of State Daniel Webster secretly funded a propaganda campaign that convinced Maine leaders that a compromise was wise; Webster used an old map that showed British claims were legitimate. The British had a different old map that showed the American claims were legitimate, so both sides thought the other had the better case. The final border between the two countries was established with the Webster–Ashburton Treaty of 1842, which gave Maine most of the disputed area, and gave the British a militarily vital connection between its provinces of Canada (present-day Quebec and Ontario) and New Brunswick.

The passion of the Aroostook War signaled the increasing role lumbering and logging were playing in the Maine economy, particularly in the central and eastern sections of the state. Bangor arose as a lumbering boom-town in the 1830s, and a potential demographic and political rival to Portland. Bangor became for a time the largest lumber port in the world, and the site of furious land speculation that extended up the Penobscot River valley and beyond.

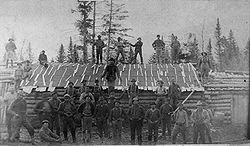

Loggers at Russell Camp, Aroostook County, ca. 1900

Loggers at Russell Camp, Aroostook County, ca. 1900

Industrialization in 19th century Maine took a number of forms, depending on the region and period. The river valleys, particularly the Kennebec and Penobscot, became virtual conveyor belts for the making of lumber beginning in the 1820’s-30’s. Logging crews penetrated deep into the Maine woods in search of pine (and later spruce) and floated it down to sawmills gathered at waterfalls. The lumber was then shipped from ports such as Bangor, Ellsworth and Cherryfield all over the world.

Partly because of the lumber industry’s need for transportation, and partly due to the prevalence of wood and carpenters along a very long coastline, shipbuilding became an important industry in Maine’s coastal towns. The Maine merchant marine was huge in proportion to the state’s population, and ships and crews from communities such as Bath, Brewer, and Belfast could be found all over the world. The building of very large wooden sailing ships continued in some places into the early 20th century.

Cotton textile mills migrated to Maine from Massachusetts beginning in the 1820s. The major site for cotton textile manufacturing was Lewiston on the Androscoggin River, the most northerly of the Waltham-Lowell system towns (factory towns modeled on Lowell, Massachusetts). The twin cities of Biddeford and Saco, as well as Augusta, Waterville, and Brunswick also became important textile manufacturing communities. These mills were established on waterfalls and amidst farming communities as they initially relied on the labor of farm-girls engaged on short-term contracts. In the years after the Civil War, they would become magnets for immigrant labor.

In addition to fishing, important 19th century industries included granite and slate quarrying, brick-making, and shoe-making.

Starting in the early 20th century, the pulp and paper industry spread into the Maine woods and most of the river valleys from the lumbermen, so completely that Ralph Nader would famously describe Maine in the 1960s as a “paper plantation”. Entirely new cities, such as Millinocket and Rumford were established on the upper-most reaches of the large rivers.

For all this industrial development, however, Maine remained a largely agricultural state well into the 20th century, with most of its population living in small and widely-separated villages. With short growing seasons,rocky soil, and relative remoteness from markets, Maine agriculture was never as prosperous as in other states; the populations of most farming communities peaked in the 1850s, declining steadily thereafter.