History of the YMCA

A Brief History of the YMCA Movement

Beginnings in London

In 1844, industrialized London was a place of great turmoil and despair. For the young men who migrated to the city from rural areas to find jobs, London offered a bleak landscape of tenement housing and dangerous influences.

Twenty-two-year-old George Williams, a farmer-turned-department store worker, was troubled by what he saw. He joined 11 friends to organize the first Young Mens Christian Association (YMCA), a refuge of Bible study and prayer for young men seeking escape from the hazards of life on the streets.

Although an association of young men meeting around a common purpose was nothing new, the Y offered something unique for its time. The organization drive to meet social need in the community was compelling, and its openness to members crossed the rigid lines separating English social classes.

Years later, retired Boston sea captain Thomas Valentine Sullivan, working as a marine missionary, noticed a similar need to create a safe home away from home for sailors and merchants. Inspired by the stories of the Y in England, he led the formation of the first U.S. YMCA at the Old South Church in Boston on December 29, 1851.

The Young Men Christian Association was founded in London, England, on June 6, 1844, in response to unhealthy social conditions arising in the big cities at the end of the Industrial Revolution (roughly 1750 to 1850). Growth of the railroads and centralization of commerce and industry brought many rural young men who needed jobs into cities like London. They worked 10 to 12 hours a day, six days a week.

Far from home and family, these young men often lived at the workplace. They slept crowded into rooms over the company shop, a location thought to be safer than Londons tenements and streets. Outside the shop things were bad open sewers, pickpockets, thugs, beggars, drunks, lovers for hire and abandoned children running wild by the thousands.

George Williams, born on a farm in 1821, came to London 20 years later as a sales assistant in a draper shop, a forerunner of today department store. He and a group of fellow drapers organized the first YMCA to substitute Bible study and prayer for life on the streets. By 1851 there were 24 YMCA’s in Great Britain, with a combined membership of 2,700. That same year the Y arrived in North America, first in Montreal and then Boston.

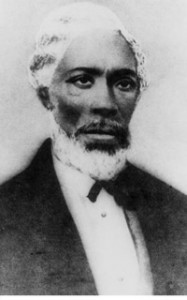

Anthony Bowen founded the first African American YMCA in 1853. The idea proved popular everywhere. In 1853, the first YMCA for African Americans was founded in Washington, D.C., by Anthony Bowen, a freed slave. The next year the first international convention was held in Paris. At the time there were 397 separate YMCA’s in seven nations, with 30,369 members total.

Anthony Bowen founded the first African American YMCA in 1853. The idea proved popular everywhere. In 1853, the first YMCA for African Americans was founded in Washington, D.C., by Anthony Bowen, a freed slave. The next year the first international convention was held in Paris. At the time there were 397 separate YMCA’s in seven nations, with 30,369 members total.

The YMCA idea, which began among evangelicals, was unusual because it crossed the rigid lines that separated all the different churches and social classes in England in those days. This openness was a trait that would lead eventually to including in YMCA’s all men, women and children, regardless of race, religion or nationality. Also, its target of meeting social need in the community was dear from the start.

George Williams was knighted by Queen Victoria in 1894 for his YMCA work and buried in 1905 under the floor of St. Paul Cathedral among that nation heroes and statesmen. A large stained glass window in Westminster Abbey, complete with a red triangle, is dedicated to YMCAs, to Sir George and to Y work during the first World War.

Civil War times

In the United States during the Civil War, Y membership shrunk to one-third its size as members marched off to battle. Fifteen of the remaining Northern YMCA’s formed the U.S. Christian Commission to assist the troops and prisoners of war. It was endorsed by President Abraham Lincoln, and its 4,859 volunteers included the American poet Walt Whitman. Among other accomplishments, it gave more than 1 million Bibles to fighting men. It was the beginning of a commitment to working with soldiers and sailors that continues to this day through the Armed Services YMCA’s.

Only 59 YMCA’s were left by war end, but a rapid rebuilding followed, and four years later there were 600 more. The focus was on saving souls, with saloon and street corner preaching, lists of Christian boarding houses, lectures, libraries and meeting halls, most of them in rented quarters.

But seeds of future change were there. In 1866, the influential New York YMCA adopted a fourfold purpose: The improvement of the spiritual, mental, social and physical condition of young men.

Camp leaders at the first YMCA camp in the United States in 1887.

Camp leaders at the first YMCA camp in the United States in 1887.

In those early days, YMCA’s were run almost entirely by volunteers. There were a handful of paid staff members before the Civil War who kept the place clean, ran the library and served as corresponding secretaries. But it was until the 1880s, when YMCA’s began putting up buildings in large numbers, that most associations thought they needed someone there full time.

Gyms and swimming pools came in at that time, too, along with big auditoriums and bowling alleys. Hotel-like rooms with bathrooms down the hall, called dormitories or residences, were designed into every new YMCA building, and would continue to be until the late 1950’s. Income from rented rooms was a great source of funds for YMCA activities of all kinds. Residences would make a major financial contribution to the movement for the next century.

YMCAs took up boys work and organized summer camps. They set up exercise drills in classes forerunners of today aerobics using wooden dumbbells, heavy medicine balls and so-called Indian clubs, which resembled graceful, long-necked bowling pins. YMCA’s organized college students for social action, literally invented the games of basketball and volleyball and served the special needs of railroad men who had no place to stay when the train reached the end of the line. By the 1890s, the fourfold purpose was transformed into the triangle of spirit, mind and body.

Moody and Mott

Through the influence of nationally known lay evangelists Dwight L. Moody (1837- 1899) and John Mott (1865-1955), who dominated the movement in the last half of the 19th and first half of the 20th centuries respectively, the American YMCA’s sent workers by the thousands overseas, both as missionary-like YMCA secretaries and as war workers.

The first foreign work secretaries, as they were called, reflected the huge missionary outreach by Christian churches near the turn of the century. But instead of churches, they organized YMCA’s that eventually were placed under local control. Both Moody and Mott served for lengthy periods as paid professional staff members of the YMCA movement. Both maintained lifelong connections with it.

YMCA swimming, 1910-1914 (circa).

YMCA swimming, 1910-1914 (circa).

The United States entered World War I in April 1917. Mott, on his own, involved the YMCA movement in running the military canteens, called post exchanges today, in the United States and France. YMCA’s led fundraising campaigns that raised $235 million for those YMCA operations and other wartime causes, and hired 25,926 Y workers5,145 of them women to run the canteens.

It also took on war relief for both refugees and prisoners of war on both sides, and worked to ease the path of African American soldiers returning to the segregated South. Y secretaries from China supervised the Chinese laborers brought to Europe to unload ships, dig trenches and clear the battlefields after the war. Y.C. James Yen, a Yale graduate working with YMCAs in France, developed a simple Chinese alphabet of 100 characters that became a major weapon in wiping out illiteracy in China. Funds left over from war work helped in the 1920’s to spur a Y building boom, outreach to small towns and counties, work with returning black troops and blossoming of YMCA trade schools and colleges.

Buddy, can you spare a dime?

The Great Depression brought dramatic drops in Y income, some as high as 50 percent. A number of associations had taken up direct relief of the poor beginning in 1928, as employment mounted before the stock market crash of 1929. When direct relief was taken over by the federal government in 1933, it released YMCA’s and other nonprofits from their welfare tasks.

Forced to re-evaluate themselves by hard times and by pressure from militant student YMCA’s, community YMCA’s became aware of social problems as never before and accelerated their partnerships with other social welfare agencies. Programs and mission were reviewed as well. Some results were joint community projects, renewed emphasis on group work and more work through organized classes and lectures. YMCA’s were forced to prove to their communities that both character-building agencies and welfare agencies were needed, especially in times of stress.

Between 1929 and 1933, Bible class enrollment fell by 60 percent and residence use was down, but exercise and educational classes were both up, along with vocational training and camping.

A typical Y program of the day was the Leisure Time League in Minneapolis. It drew thousands to that YMCA in 1932 to unite unemployed young men who desire to maintain their physical and mental vigor and wish to train themselves for greater usefulness and service to themselves and the community, reported the association. The program offered a wide range of free services such as medical assistance, physical programs, school classes on a dozen subjects and recreation. As conditions improved even slightly, they went back to work. A few were left behind in most cases, those considered unemployable. The YMCA offered them vocational training.

The idea spread widely and YMCA’s discovered they could survive handily if they served a large number of people and had low building payments. In fact, the Chicago Y was able to organize a new South Shore branch in the depths of the Depression.

Wartime challenges

During World War II, the National Council of YMCA’s (now the YMCA of the USA) joined with YMCA’s around the world to assist prisoners of war in 36 nations. It also helped form the United Service Organization (USO), which ran drop-in centers for servicepeople and sent performers abroad to entertain the troops. YMCA’s worked with displaced persons and refugees as well, and sent both workers and money abroad after the war to help rebuild damaged YMCA buildings.

After more than two decades of study and trial YMCA youth secretaries in 1944 agreed to put a national seal of approval on what was already widespread in the movement to focus their energies on four programs that involved work in small groups. They became known as the four fronts or four platforms of Youth Work: a father-son program called Y-Indian Guides, and three boy clubs Gra-Y for those in grade school, Junior Hi-Y and Hi-Y. (There would eventually be all-female and coed models as well.)

Times of change

At the close of the war, YMCA’s had changed. Sixty-two percent were admitting women, and other barriers began to fall one after the other, with families the new emphasis, and all races and religions included at all levels of the organization. The rapidly expanding suburbs drew the YMCA’s with them, sometimes abandoning the old residences and downtown buildings that no longer were efficient or necessary.

In 1958, the U.S. and Canadian YMCA’s launched Buildings for Brotherhood in which the two nations raised $55 million which was matched by $6 million overseas. The result was 98 Y buildings renovated, improved or built new in 32 countries.

In what could be called the Great Disillusion of 1965-1975, the nation was rocked by turmoil that included the Vietnam War, the forced resignation of a U.S. president, the outbreak of widespread drug abuse among the middle class, assassination of major political leaders, and a loss of confidence in institutions.

The YMCAs, in response, were challenged by National General Secretary James Bunting to change their ways. He said the choice was either to keep learning or to become 20th- century Pharisees clinging to forms and theories that were once valid expressions of the best that was known, but that today are outdated and irrelevant.

With national YMCA support and federal aid, new outreach efforts were taken up by community YMCA’s in 150 cities. The Ys poured their own money and talent into outreach as well. Outreach programs were not new to the organization, but the size and scope involved were new.

The four-fronts youth programs withered for lack of attention, dying out entirely in many major centers, but holding fast in YMCA camping and in parts of the Midwest and much of the South. When federal aid dried up, money troubles began to reappear, as Y’s struggled to keep faith with those they were helping.

An even more insidious problem was in the mix. Long schooled in conciliation, Y people found themselves being confronted aggressively both at home and abroad. It was particularly hard to deal with and discouraging. Beginning in 1970 the fraternal secretaries serving YMCA’s overseas were being called home. Some buildings in U.S. cities were shuttered and residences dosed for lack of clientele and insufficient funds for proper maintenance. Y leaders were urged to become more businesslike in both their appearance and their operations, a topic raised by Y boards since the 1920’s.

Trends

After 1975, the old physical programming featured by YMCA’s for a century began to perk up as interest in healthy lifestyles increased nationwide. By 1980, pressure for up-to- date buildings and equipment brought on a boom in construction that lasted through the decade.

Child care for working parents, an extension of what YMCA’s had done informally for years, came with a rush in 1983 and quickly joined health and fitness, camping and residences as a major source of YMCA income.

Character Development and Asset-Based Approach

During the 1980’s and 90’s, the ideas of values clarification were slowly replaced by ideas of character. The moral upbringing of children had been considered the sole domain of the family, and enabling the child to discover his or her own ethical system was the goal. But by the mid to late 80’s, this was seen as contributing to a morally bankrupt society, in which there is no notion of virtue (or of vice), just different points of view. The ideas of character development and civic virtues became central, with Bennet The Book of Virtues hitting the best-seller lists and organizations such as Character Counts! being born. Preach what you practice became as much a part of the ideal of youth development as practice what you preach, and it takes a village replaced the family job to develop morals.

The YMCA movement had been involved in character development from the beginning, but in an implicit and practical focus rather than an explicit one. (George Williams stated this perfectly in his response to how he would respond to a young man who said that he had lost his belief in Jesus, by saying that his first act would be to see that the young man had dinner.) The YMCA movement studied the issue and emerged with four core values caring, honesty, respect and responsibility and promptly began to incorporate these in all programming in an explicit and conscious way.

The first Healthy Kids Day was conducted in 1992.

The first Healthy Kids Day was conducted in 1992.

During the 90’s, a tremendous change occurred in the field of youth development. Previously, the focus had been on the deficit model, in other words, what went wrong with the youth who got into trouble, and how could they be corrected. But the same way that prevention and development of health, rather than just the cure of disease pervaded the medical world, youth workers and academics started to look at what contributes to healthy development and prevents problem an assets model. YMCA of the USA collaborated with Search Institute on studying this issue in depth and coming up with practical results.

The research showed 30 (later increased to 40) developmental assets that positively correlated with pro-social and healthy behaviors in youth, and negatively correlated with anti-social and unhealthy behaviors. The more assets a youth has, the more likely he or she is to behave well, the less likely to engage in risky behaviors. This not only provided a road map for YMCA’s to follow in creating healthy kids, families and communities, but also was an inherent proof of the effectiveness of youth programs.

It also showed a wider focus than had been thought possible. It doesnt matter if a program consists of sports, music, a teen center, mentoring or aerobics, or if it aimed at reducing teen pregnancy, smoking or crime. If it provides one or more of the developmental assets, it will reduce the overall risk of any kind of negative behavior, and raise the likelihood of positive behavior (the material above comes from the YMCA).