February 19, 1942 Japanese American Internment

Japanese Relocation – Government Film (1942)

“Japanese Relocation” is a short film produced by the U.S. Office of War Information and distributed by the War Activities Committee of the Motion Picture Industry. It is a propaganda film, justifying and explaining Japanese American internment on the West Coast during World War II. It is narrated by Milton Eisenhower.

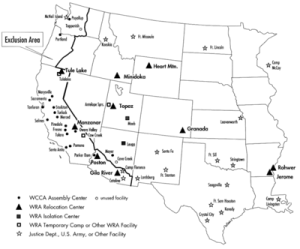

Internment camps and further institutions of the War Relocation Authority in the western United States.

Internment camps and further institutions of the War Relocation Authority in the western United States.

Japanese American internment was the World War IIinternment in “War Relocation Camps” of over 110,000 people of Japanese heritage who lived on the Pacific coast of the United States. The U.S. government ordered the internment in 1942, shortly after Imperial Japan‘s attack on Pearl Harbor. The internment of Japanese Americans was applied unequally as a geographic matter: all who lived on the West Coast were interned, while in Hawaii, where 150,000-plus Japanese Americans comprised over one-third of the population, only 1,200 to 1,800 were interned. Sixty-two percent of the internees were American citizens. President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized the internment with Executive Order 9066, issued February 19, 1942, which allowed local military commanders to designate “military areas” as “exclusion zones,” from which “any or all persons may be excluded.” This power was used to declare that all people of Japanese ancestry were excluded from the entire Pacific coast, including all of California and much of Oregon, Washington and Arizona, except for those in internment camps.

In 1944, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the exclusion orders. The Court limited its decision to the validity of the exclusion orders, adding, “The provisions of other orders requiring persons of Japanese ancestry to report to assembly centers and providing for the detention of such persons in assembly and relocation centers were separate, and their validity is not in issue in this proceeding.” The United States Census Bureau assisted the internment efforts by providing confidential neighborhood information on Japanese Americans. The Bureau’s role was denied for decades, but was finally proven in 2007. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter conducted an investigation to determine whether putting Japanese Americans into internment camps was justified well enough by the government. He appointed the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) to investigate the camps. The commission’s report, named “Personal Justice Denied,” found little evidence of Japanese disloyalty at the time and recommended the government pay reparations to the survivors. They formed a payment of $20,000 to each individual internment camp survivor. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed into law legislation that apologized for the internment on behalf of the U.S. government. The legislation said that government actions were based on “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” The U.S. government eventually disbursed more than $1.6 billion in reparations to Japanese Americans who had been interned and their heirs.

In 1944, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the exclusion orders. The Court limited its decision to the validity of the exclusion orders, adding, “The provisions of other orders requiring persons of Japanese ancestry to report to assembly centers and providing for the detention of such persons in assembly and relocation centers were separate, and their validity is not in issue in this proceeding.” The United States Census Bureau assisted the internment efforts by providing confidential neighborhood information on Japanese Americans. The Bureau’s role was denied for decades, but was finally proven in 2007. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter conducted an investigation to determine whether putting Japanese Americans into internment camps was justified well enough by the government. He appointed the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) to investigate the camps. The commission’s report, named “Personal Justice Denied,” found little evidence of Japanese disloyalty at the time and recommended the government pay reparations to the survivors. They formed a payment of $20,000 to each individual internment camp survivor. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed into law legislation that apologized for the internment on behalf of the U.S. government. The legislation said that government actions were based on “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” The U.S. government eventually disbursed more than $1.6 billion in reparations to Japanese Americans who had been interned and their heirs.

After Pearl Harbor

San Francisco Examiner, February 1942.

San Francisco Examiner, February 1942.

Of 127,000 Japanese Americans living in the continental United States at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack, 112,000 resided on the West Coast. About 80,000 were nisei (literal translation: “second generation”; Japanese people born in the United States and holding American citizenship) and sansei (literal translation: “third generation”; the sons or daughters of nisei). The rest were issei (literal translation: “first generation”; immigrants born in Japan who were ineligible for U.S. citizenship).

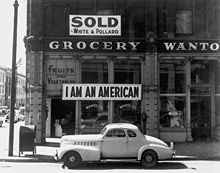

A Japanese American unfurled this banner the day after the Pearl Harbor attack. This Dorothea Lange photograph was taken in March 1942, just prior to the man’s internment.

Children at the Weill public school in San Francisco pledge allegiance to the American flag in April 1942, prior to the internment of Japanese Americans.

The attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 led military and political leaders to suspect that Imperial Japan was preparing a full-scale attack on the West Coast of the United States. Japan’s rapid military conquest of a large portion of Asia and the Pacific between 1936 and 1942 made its military forces seem unstoppable to some Americans. American public opinion initially stood by the large population of Japanese-Americans living on the West Coast, with the Los Angeles Times characterizing them as “good Americans, born and educated as such.” Many Americans believed that their loyalty to the United States was unquestionable. However, six weeks after the attack, public opinion turned against Japanese Americans living in on the West Coast, as the press and other Americans became nervous about the potential for fifth column activity.

Though the administration (including the President Franklin D. Roosevelt and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover) dismissed all rumors of Japanese-American espionage on behalf of the Japanese War effort, pressure mounted upon the Administration as the tide of public opinion turned against Japanese-Americans. Civilian and military officials had serious concerns about the loyalty of the ethnic Japanese after the Niihau Incident which immediately followed the attack on Pearl Harbor, when a civilian Japanese national and two Hawaiian-born ethnic Japanese on the island of Ni’ihau violently freed a downed and captured Japanese naval airman, attacking their fellow Ni’ihau islanders in the process. Several concerns over the loyalty of ethnic Japanese seemed to stem from racial prejudice rather than evidence of actual malfeasance. Major Karl Bendetsen and Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, head of the Western Command, each questioned Japanese American loyalty. DeWitt, who administered the internment program, repeatedly told newspapers that “A Jap’s a Jap” and testified to Congress,

Though the administration (including the President Franklin D. Roosevelt and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover) dismissed all rumors of Japanese-American espionage on behalf of the Japanese War effort, pressure mounted upon the Administration as the tide of public opinion turned against Japanese-Americans. Civilian and military officials had serious concerns about the loyalty of the ethnic Japanese after the Niihau Incident which immediately followed the attack on Pearl Harbor, when a civilian Japanese national and two Hawaiian-born ethnic Japanese on the island of Ni’ihau violently freed a downed and captured Japanese naval airman, attacking their fellow Ni’ihau islanders in the process. Several concerns over the loyalty of ethnic Japanese seemed to stem from racial prejudice rather than evidence of actual malfeasance. Major Karl Bendetsen and Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, head of the Western Command, each questioned Japanese American loyalty. DeWitt, who administered the internment program, repeatedly told newspapers that “A Jap’s a Jap” and testified to Congress,

I don’t want any of them [persons of Japanese ancestry] here. They are a dangerous element. There is no way to determine their loyalty… It makes no difference whether he is an American citizen, he is still a Japanese. American citizenship does not necessarily determine loyalty… But we must worry about the Japanese all the time until he is wiped off the map.

DeWitt also sought approval to conduct search and seizure operations aimed at preventing alien Japanese from making radio transmissions to Japanese ships. The Justice Department declined, stating that there was no probable cause to support DeWitt’s assertion, as the FBI concluded that there was no security threat. On January 2, the Joint Immigration Committee of the California Legislature sent a manifesto to California newspapers which attacked “the ethnic Japanese,” who it alleged were “totally unassimilable.” This manifesto further argued that all people of Japanese heritage were loyal subjects of the Emperor of Japan; Japanese language schools, furthermore, according to the manifesto, were bastions of racism which advanced doctrines of Japanese racial superiority. The manifesto was backed by the Native Sons and Daughters of the Golden West and the California Department of the American Legion, which in January demanded that all Japanese with dual citizenship be placed in concentration camps. Internment was not limited to those who had been to Japan, but included a small number of German and Italian enemy aliens. By February, Earl Warren, the Attorney General of California, had begun his efforts to persuade the federal government to remove all people of Japanese heritage from the West Coast.

DeWitt also sought approval to conduct search and seizure operations aimed at preventing alien Japanese from making radio transmissions to Japanese ships. The Justice Department declined, stating that there was no probable cause to support DeWitt’s assertion, as the FBI concluded that there was no security threat. On January 2, the Joint Immigration Committee of the California Legislature sent a manifesto to California newspapers which attacked “the ethnic Japanese,” who it alleged were “totally unassimilable.” This manifesto further argued that all people of Japanese heritage were loyal subjects of the Emperor of Japan; Japanese language schools, furthermore, according to the manifesto, were bastions of racism which advanced doctrines of Japanese racial superiority. The manifesto was backed by the Native Sons and Daughters of the Golden West and the California Department of the American Legion, which in January demanded that all Japanese with dual citizenship be placed in concentration camps. Internment was not limited to those who had been to Japan, but included a small number of German and Italian enemy aliens. By February, Earl Warren, the Attorney General of California, had begun his efforts to persuade the federal government to remove all people of Japanese heritage from the West Coast.

Taken by Russell Lee, this photograph is labeled “Tagged for evacuation, Salinas, California, May 1942.”

Those that were as little as 1/16 Japanese could be placed in internment camps. There is evidence supporting the argument that the measures were racially motivated, rather than a military necessity. Bendetsen, promoted to colonel, said in 1942 “I am determined that if they have one drop of Japanese blood in them, they must go to camp.” Upon the bombing of Pearl Harbor and pursuant to the Alien Enemies Act, Presidential Proclamations 2525, 2526 and 2527 were issued designating Japanese, German and Italian nationals as enemy aliens. Information from the CDI was used to locate and incarcerate foreign nationals from Japan, Germany and Italy (although Germany and Italy did not declare war on the U.S. until December 11). Presidential Proclamation 2537 was issued on January 14, 1942, requiring aliens to report any change of address, employment or name to the FBI. Enemy aliens were not allowed to enter restricted areas. Violators of these regulations were subject to “arrest, detention and internment for the duration of the war.”