African Americans in the Military

Blacks in the Military

Blacks in the Military (3:12) TV-PG, Learn how blacks serving in WWII helped forward the Civil Rights Movement and more.

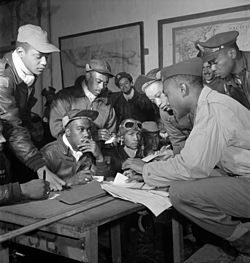

The 332nd Fighter Group attends a briefing in Italy in 1945.

The 332nd Fighter Group attends a briefing in Italy in 1945.

The Military history of African Americans spans from the arrival of the first black slaves during the colonial history of the United States to the present day. There has been no war fought by or within the United States in which African Americans did not participate, including the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War, the Civil War, the Spanish American War, the World Wars, theKorean War, the Vietnam War, the Gulf War, and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as other minor conflicts.

Revolutionary War

African-Americans as slaves and free blacks, served on both sides during the war. Black soldiers served in northern militias from the outset, but this was forbidden in the South, where slave-owners feared arming slaves. Lord Dunmore, the Royal Governor of Virginia, issued an emancipation proclamation in November 1775, promising freedom to runaway slaves who fought for the British; Sir Henry Clinton issued a similar edict in New York in 1779. Over 100,000 slaves escaped to the British lines, although possibly as few as 1,000 served under arms. Many of the rest served as orderlies, mechanics, laborers, servants, scouts and guides, although more than half died in smallpox epidemics that swept the British forces, and many were driven out of the British lines when food ran low. Despite Dunmore’s promises, the majority were not given their freedom. Many Black Loyalists‘ descendants now live in Canada.

Crispus Attucks is seen by some as a patriot of the pre-Revolutionary War era. As part of a rioting mob, he was killed in 1770 during an attack on British soldiers guarding the custom house which came to be known as the Boston Massacre.

Crispus Attucks is seen by some as a patriot of the pre-Revolutionary War era. As part of a rioting mob, he was killed in 1770 during an attack on British soldiers guarding the custom house which came to be known as the Boston Massacre.

In response, and because of manpower shortages, Washington lifted the ban on black enlistment in the Continental Army in January 1776. All-black units were formed in Rhode Island and Massachusetts; many were slaves promised freedom for serving in lieu of their masters; another all-African-American unit came from Haiti with French forces. At least 5,000 African-American soldiers fought as Revolutionaries, and at least 20,000 served with the British.

Peter Salem and Salem Poor are the most noted of the African American Patriots during this era, while Black Loyalist Colonel Tye became one of the most successful commanders of the war.

Black volunteers also served with various of the South Carolina guerrilla units, including that of the “Swamp Fox”, Francis Marion, half of whose force sometimes consisted of free Blacks. These Black troops made a critical difference in the fighting in the swamps, and kept Marion’s guerrillas effective even when many of his White troops were down with malaria or yellow fever.

The first black American to fight in the Marines was John Martin, also known as Keto, the slave of a Delaware man, recruited in April 1776 without his owner’s permission by Captain of the Marines Miles Pennington of the Continental brig USS Reprisal. Martin served with the Marine platoon on the Reprisal for a year and a half and took part in many ship-to-ship battles including boardings with hand-to-hand combat, but he was lost with the rest of his unit when the brig sank in October 1777. At least 12 other black men served with various American Marine units in 1776–1777; more may have been in service but not identified as blacks in the records. However, in 1798 when the United States Marine Corps (USMC) was officially re-instituted, Secretary of War James McHenry specified in its rules: “No Negro, Mulatto or Indian to be enlisted.” Marine Commandant William Ward Burrows instructed his recruiters regarding USMC racial policy, “You can make use of Blacks and Mulattoes while you recruit, but you cannot enlist them.” This policy was in line with long-standing British naval practice which set a higher standard of unit cohesion for Marines, the unit to be made up of only one race, so that the members would remain loyal, maintain shipboard discipline and help put down mutinies. The USMC maintained this policy until 1942.

War of 1812

Painting of Battle of Lake Erie depicting one of Perry’s African American oarsmen in the boat and another African American sailor in the water.

Painting of Battle of Lake Erie depicting one of Perry’s African American oarsmen in the boat and another African American sailor in the water.

During the War of 1812, about one-quarter of the personnel in the American naval squadrons of the Battle of Lake Erie were black, and portrait renderings of the battle on the wall of the Nation’s Capitol and the rotunda of Ohio’s Capitol show that blacks played a significant role in it. Hannibal Collins, a freed slave and Oliver Hazard Perry‘s personal servant, is thought to be the oarsman in William Henry Powell‘s Battle of Lake Erie. Collins earned his freedom as a veteran of the Revolutionary War, having fought in the Battle of Rhode Island. He accompanied Perry for the rest of Perry’s naval career, and was with him at Perry’s death in Trinidad in 1819.

No legal restrictions regarding the enlistment of blacks were placed on the Navy because of its chronic shortage of manpower. The law of 1792, which generally prohibited enlistment of blacks in the Army became the United States Army’s official policy until 1862. The only exception to this Army policy was Louisiana, which gained an exemption at the time of its purchase through a treaty provision, which allowed it to opt out of the operation of any law, which ran counter to its traditions and customs. Louisiana permitted the existence of separate black militia units which drew its enlistees from freed blacks.

A militia unit, The Louisiana Battalion of Free Men of Color, and a unit of black soldiers from Santo Domingo offered their services and were accepted by General Andrew Jackson in the Battle of New Orleans, a victory that was achieved after the war was officially over.

Mexican War

A number of blacks in the Army during the Mexican War were servants of the officers who received government compensation for the services of their servants or slaves. Also, soldiers from the Louisiana Battalion of Free Men of Color participated in this war. Blacks also served on a number of naval vessels during the Mexican War, including the U.S.S. Treasure, and the U.S.S. Columbus.

Military history of African Americans in the American Civil War

The history of African Americans in the U.S. Civil War is marked by 186,097 (7,122 officers, 178,975 enlisted) African American men, comprising 163 units, who served in the Union Army during the Civil War, and many more African Americans served in the Union Navy. Both free African Americans and runaway slaves joined the fight. On the Confederate side, blacks, both free and slave, were used for labor, but the issue of whether to arm them, and under what terms, became a major source of debate amongst those in the South. At the start of the war, a Louisiana Confederate militia unit composed of free blacks was raised, but never accepted into Confederate service. On March 13, 1865 the Confederate Congress enacted a statute to allow the enlistment of African Americans but fewer than fifty were ever recruited.

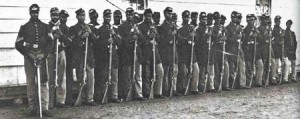

A company of 4th USCT

A company of 4th USCT

Indian Wars

From the 1870’s to the early 20th century, African American units were utilized by the United States Government to combat the Native Americans during the Indian Wars. Perhaps the most noted among this group were the Buffalo

Soldiers: Buffalo Soldiers of the 25th Infantry Regiment, 1890

Soldiers: Buffalo Soldiers of the 25th Infantry Regiment, 1890

- 9th Cavalry Regiment

- 10th Cavalry Regiment

- 24th Infantry Regiment

- 25th Infantry Regiment

- 27th Cavalry Regiment

- 28th Cavalry Regiment

At the end of the U.S. Civil War the army reorganized and authorized the formation of two regiments of black cavalry with the designations 9th and 10th U. S. Cavalry. Two regiments of infantry were formed at the same time. These units were composed of black enlisted men commanded by white officers such as Benjamin Grierson, and, occasionally, an African-American officer such as Henry O. Flipper.

From 1866 to the early-1890s these regiments served at a variety of posts in the southwest United States and Great Plains regions. During this period they participated in most of the military campaigns in these areas and earned a distinguished record. Thirteen enlisted men and six officers from these four regiments earned the Medal of Honor during the Indian Wars. In addition to the military campaigns, the “Buffalo Soldiers” served a variety of roles along the frontier from building roads to escorting the U.S. mail.

Spanish American War

Segregated company during the Spanish-American War Camp Wikoff 1898

Segregated company during the Spanish-American War Camp Wikoff 1898

After the Indian Wars ended in the 1890’s, the regiments continued to serve and participated in the Spanish-American War (including the Battle of San Juan Hill), where five more Medals of Honor were earned. They took part in the 1916 Punitive Expedition into Mexico and in the Philippine-American War. The Spanish-American War’s General Shafter preferred his “Buffalo Soldiers” to their white counterparts.

Units

In addition to the African Americans who served in Regular Army units during the Spanish American War, five African American Volunteer Army units and seven African American National Guard units also served.

Volunteer Army:

- 7th United States Volunteer Infantry (Colored Troops)

- 8th United States Volunteer Infantry (Colored Troops)

- 9th United States Volunteer Infantry (Colored Troops)

- 10th United States Volunteer Infantry (Colored Troops)

- 11th United States Volunteer Infantry (Colored Troops)

National Guard:

- 3rd Alabama Volunteer Infantry (Colored Troops)

- 8th Illinois Volunteer Infantry (Colored Troops)

- Companies A and B, 1st Indiana Volunteer Infantry (Colored Troops)

- 23rd Kansas Volunteer Infantry (Colored Troops)

- 3rd North Carolina Volunteer Infantry (Colored Troops)

- 9th Ohio Volunteer Infantry (Colored Troops)

- 6th Virginia Volunteer Infantry (Colored Troops)

Of these units, only the 9th U.S., 8th Illinois, and 23rd Kansas served outside the United States during the war. All three units served in Cuba and suffered no losses to combat.

World War I

Officers of the 366th Infantry Regiment returning home from World War I service.

Officers of the 366th Infantry Regiment returning home from World War I service.

Soldiers of the 369th (15th N.Y.) who won the Croix de Guerre for gallantry in action, 1919

Soldiers of the 369th (15th N.Y.) who won the Croix de Guerre for gallantry in action, 1919

The U.S. armed forces remained segregated through World War I. Still, many African Americans eagerly volunteered to join the Allied cause following America’s entry into the war. By the time of the armistice with Germany on November 1918, over 350,000 African Americans had served with the American Expeditionary Force on the Western Front.

Most African American units were largely relegated to support roles and did not see combat. Still, African Americans played a notable role in America’s war effort. One of the most distinguished units was the 369th Infantry Regiment, known as the “Harlem Hellfighters”, which was on the front lines for six months, longer than any other American unit in the war. 171 members of the 369th were awarded the Legion of Merit.

Corporal Freddie Stowers of the 371st Infantry Regiment that was seconded to the 157th French Army division called the Red Hand Division in need of reinforcement under the command of the General Mariano Goybet was posthumously awarded a Medal of Honor — the only African American to be so honored for actions in World War I. During action in France, Stowers had led an assault on German trenches, continuing to lead and encourage his men even after being twice wounded. Stowers died from his wounds, but his men continued the fight and eventually defeated the German troops. Stowers was recommended for the Medal of Honor shortly after his death, but the nomination was, according to the Army, misplaced. Many believed that the recommendation was intentionally ignored due to institutional racism in the Armed Forces. In 1990, under pressure from Congress, the Department of the Army launched an investigation. Based on findings from this investigation, the Army Decorations Board approved the award of the Medal of Honor to Stowers. On April 24, 1991–73 years after he was killed in action—Stowers’ two surviving sisters received the Medal of Honor from President George H.W. Bush at the White House. The success of the investigation leading to Stowers’ Medal of Honor later sparked a similar review that resulted in six African Americans being posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for actions in World War II. Vernon Baker was the only recipient who was still alive to receive his award.

Units – Some of the most notable African American units which served in World War I were: 351st Field Artillery troops on the deck of the Louisville

- 92nd Infantry Division

- 93rd Infantry Division

- 369th Infantry Regiment (“Harlem Hellfighters”; formerly the 15th New York National Guard)

- 370th Infantry Regiment (formerly the 8th Illinois)

- 371st Infantry Regiment

- 372nd Infantry Regiment

A complete list of African-American units that served in the war is published in the book Willing Patriots: Men of Color in World War One. The book is cited in the “Further Reading” section of this article.

Period between the world wars

Even though the U.S. government was nominally neutral in the wars waged by Fascists against Ethiopia and Fascists and Nazis against the Spanish Republic in the mid-1930’s, African Americans found it hard to be neutral and many became Antifascist.

Second Italo-Abyssinian War

On October 4, 1935, Fascist Italy invaded Ethiopia. Being the only non-colonized African country besides Liberia, the invasion of Ethiopia caused a profound response amongst African Americans. African Americans organized to raise money for medical supplies, and many volunteered to fight for the African kingdom. Within eight months, however, Ethiopia was overpowered by the advanced weaponry and mustard gas of the Italian forces.

Many years later Haile Selassie I would comment on the efforts: “We can never forget the help Ethiopia received from Negro Americans during the crisis…It moved me to know that Americans of African descent did not abandon their embattled brothers, but stood by us.”

Spanish Civil War

When General Franco rebelled against the newly established secular Spanish Republic, a number of African Americans volunteered to fight for Republican Spain. Many African Americans who were in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade had Communist ideals. Among these, there was Vaughn Love who went to fight for the Spanish loyalist cause because he considered Fascism to be the “enemy of all black aspirations.”

African-American activist and World War I veteran Oliver Law, fighting in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade during the Spanish Civil War, is believed to have been the first African-American officer to command an integrated unit of soldiers.

James Peck was an African American man from Pennsylvania who was turned down when he applied to become a military pilot in the US. He then went on to serve in the Spanish Republican Air Force until 1938. Peck was credited with shooting down 5 Aviación Nacional planes, 2 Heinkel He-51s from the Legion Condor and 3 Fiat CR.32 Fascist Italian fighters.

Salaria Kee was a young African American nurse from Harlem Hospital who served as a military nurse with the American Medical Bureau in the Spanish Civil War. She was one of the two only African American female volunteers in the midst of the war-torn Spanish Republican areas. When Salaria came back from Spain she wrote the pamphlet ‘A Negro Nurse in Spain’ and tried to raise funds for the beleaguered Spanish Republic.

World War II

Despite a high enlistment rate in the U.S. Army, African Americans were not treated equally. Racial tensions existed. At parades, church services, in transportation and canteens the races were kept separate.

Many soldiers of color served their country with distinction during World War II. There were 125,000 African Americans who were overseas in World War II. Famous segregated units, such as the Tuskegee Airmen and 761st Tank Battalion and the lesser-known but equally distinguished 452nd Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalion proved their value in combat, leading to desegregation of all U.S. Armed Forces by order of President Harry S. Truman in July 1948 via Executive Order 9981.

Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. served as commander of the famed Tuskegee Airmen during the War. He later went on to become the first African American general in the United States Air Force. His father, Benjamin O. Davis, Sr., had been the first African American Brigadier General in the Army (1940).

Doris Miller, a Navy mess attendant, was the first African American recipient of the Navy Cross, awarded for his actions during the attack on Pearl Harbor. Miller had voluntarily manned an anti-aircraft gun and fired at the Japanese aircraft, despite having no prior training in the weapon’s use.

In 1944, the Golden Thirteen became the Navy’s first African American commissioned officers. Samuel L. Gravely, Jr. became a commissioned officer the same year; he would later be the first African American to command a US warship, and the first to be an admiral.

The Port Chicago disaster on July 17, 1944, was an explosion of about 2,000 tons of ammunition as it was being loaded onto ships by black Navy soldiers under pressure from their white officers to hurry. The explosion in Northern California killed 320 military and civilian workers, most of them black. The aftermath led to the Port Chicago Mutiny, the only case of a full military trial for mutiny in the history of the U.S. Navy against 50 Afro-American sailors who refused to continue loading ammunition under the same dangerous conditions. The trial was observed by the then young lawyer Thurgood Marshall and ended in conviction of all of the defendants. The trial was immediately and later criticized for not abiding by the applicable laws on mutiny, and it became influential in the discussion of desegregation.

During World War II, most African American soldiers still served only as truck drivers and as stevedores (except for some separate tank battalions and Army Air Forces escort fighters). In the midst of the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944, General Eisenhower was severely short of replacement troops for existing military units which were totally white in composition. Consequently, he made the decision to allow African American soldiers to pick up a weapon and join the white military units to fight in combat for the first time. More than 2,000 black soldiers had volunteered to go to the front. This was an important step toward a desegregated United States military. A total of 708 African Americans were killed in combat during World War II.

In 1945, Frederick C. Branch became the first African-American United States Marine Corps officer.

Units

The Tuskegee Airmen were the first African-American pilots in United States military history; they flew with distinction during World War II. Portrait of Tuskegee airman Edward M. Thomas by photographer Toni Frissell, March 1945.

The Tuskegee Airmen were the first African-American pilots in United States military history; they flew with distinction during World War II. Portrait of Tuskegee airman Edward M. Thomas by photographer Toni Frissell, March 1945.

Several Tuskegee airmen at Ramitelli, Italy, March 1945.

Several Tuskegee airmen at Ramitelli, Italy, March 1945.

12th AD soldier with German prisoners of war, April 1945.

12th AD soldier with German prisoners of war, April 1945.

Americans captured during the Battle of the Bulge, December 1944

Americans captured during the Battle of the Bulge, December 1944

Battery A of the 452nd AAA Battalion, November 9, 1944

Battery A of the 452nd AAA Battalion, November 9, 1944

African American soldiers in Burma stop work briefly to read President Truman’s Proclamation of Victory in Europe, May 9, 1945

Some of the most notable African American Army units which served in World War II were:

- 92nd Infantry Division

- 93rd Infantry Division

- 2nd Cavalry Division

- Air Corps Units

- Non Divisional Units

- Anti-Aircraft Artillery Unit

- Infantry Units

- Cavalry/Armor Units

- Field Artillery Units

-

-

- 333rd Field Artillery Battalion

- 349th Field Artillery Battalion

- 350th Field Artillery Battalion

- 351st Field Artillery Battalion

- 353rd Field Artillery Battalion

- 578th Field Artillery Battalion

- 593rd Field Artillery Battalion

- 594th Field Artillery Battalion

- 595th Field Artillery Battalion

- 596th Field Artillery Battalion

- 597th Field Artillery Battalion

- 598th Field Artillery Battalion

- 599th Field Artillery Battalion

- 600th Field Artillery Battalion

- 686th Field Artillery Battalion

- 777th Field Artillery Battalion

- 795th Field Artillery Battalion

- 930th Field Artillery Battalion, Illinois National Guard

- 931st Field Artillery Battalion, Illinois National Guard

- 969th Field Artillery Battalion

- 971st Field Artillery Battalion

- 973rd Field Artillery Battalion

- 993rd Field Artillery Battalion

- 999th Field Artillery Battlaion

-

-

- Tank Destroyer Units

- 614th Tank Destroyer Battalion

- 646th Tank Destroyer Battalion

- 649th Tank Destroyer Battalion

- 659th Tank Destroyer Battalion

- 669th Tank Destroyer Battalion

- 679th Tank Destroyer Battalion

- 795th Tank Destroyer Battalion

- 827th Tank Destroyer Battalion

- 828th Tank Destroyer Battalion

- 829th Tank Destroyer Battalion

- 846th Tank Destroyer Battalion

- Tank Destroyer Units

Two segregated units were organized by the United States Marine Corps:

http://www.defense.gov/home/features/2007/blackhistorymonth/timeline.html