History of Newark, New Jersey

Newark Walking Tour 1: History

Built to handle herds of livestock on their way to market, Broad Street has proved wide enough to sustain three centuries of growth. The city’s Puritan founders shoved other religions to the periphery for decades, dictating who could worship on Broad Street. Yet they also were foresighted enough to anchor the town at either end with parkland. (Slideshow by Scott Lituchy).

History of Newark, New Jersey

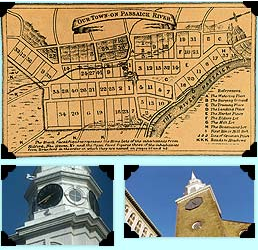

1874 bird’s-eye view of Newark

1874 bird’s-eye view of Newark

Founded by a group of disciplined Puritans, Newark is often called the City of Churches for the plethora of churches found in the area.

The New Haven Colony founders, Puritans who had fled England to establish a strict theocracy, were displeased by the imposed merger with their liberal neighbors. The New Haven colonists believed that only members of the Puritan church should be allowed to vote, and that only the children of church members could be baptized, strictures that did not appear in the new colony’s constitution.

Determined to pursue their theocracy elsewhere, the New Haven Puritans sent Robert Treat and John Gregory to meet with Philip Carteret, the new Royal Governor of New Jersey. They chose a site to settle near Elizabethtown, up the bay and along the Passaic River. In May of 1666, Puritan settlers led by Treat purchased the land directly from the Hackensack Indians for goods — including gunpowder, one hundred bars of lead, twenty axes, twenty coats, guns, pistols, swords, kettles, blankets, knives, beer, and ten pairs of breeches — valued at $750, a percentage of which was assessed upon every family that arrived in the new colony within the first year of its settlement.

Bark from the locally abundant tamarack trees provided tannin for leather tanning, and with the completion of the Morris Canal in the 1830’s, the development of the Essex Railroad, the turnpikes between Newark and Elizabeth, Belleville, New Brunswick, Springfield and Pompton, and Newark Bay, Newark was situated in the middle of a burgeoning modern transportation network.

Bark from the locally abundant tamarack trees provided tannin for leather tanning, and with the completion of the Morris Canal in the 1830’s, the development of the Essex Railroad, the turnpikes between Newark and Elizabeth, Belleville, New Brunswick, Springfield and Pompton, and Newark Bay, Newark was situated in the middle of a burgeoning modern transportation network.

Officially achieving city status in 1836, Newark was suddenly the epicenter of one of the nation’s major industrial hubs. In 1770, there was one leather tannery in Newark. In 1792, there were three. By 1837, there were 155 patent leather manufacturers in the city, producing an amount of leather then-valued at $899,200. Besides the production of leather for shoes, Newark manufactured carriages, coaches, lace, and hats. Founded in Newark in 1840, the Ballantine Brewing plants covered 12 acres in the1880’s, making it the sixth largest brewer in the nation. The city was also known for its cider and quarries.

In the 1800’s, the city’s industrial boom was made possible by the first wave of immigrants moving to Newark. Specifically, the Irish came to the area in the 1820’s to work on the construction of the Morris Canal, which at its peak carried 899,220 tons of freight through a system of 23 water-powered inclined planes and 34 locks that climbed 914 feet above sea level across New Jersey. German immigrants began arriving in the 1840’s and ’50’s as refugees of the failed revolution of 1848. By 1865, a third of Newark’s population was of German descent, and between 1840 and 1870, Newark’s population increased from 17,290 to 105,000.

African Americans began moving to Newark in the late 1800’s, and especially during the World War I factory boom. Almost 22,000 blacks arrived between 1920 and 1930. War-related industry prompted another boom in the African American community, which tripled in size between 1940 and 1960, at that point 34 percent of Newark’s population. As many former Newarkers moved to the suburbs, African Americans composed 54 percent of the city’s population by 1970.

African Americans began moving to Newark in the late 1800’s, and especially during the World War I factory boom. Almost 22,000 blacks arrived between 1920 and 1930. War-related industry prompted another boom in the African American community, which tripled in size between 1940 and 1960, at that point 34 percent of Newark’s population. As many former Newarkers moved to the suburbs, African Americans composed 54 percent of the city’s population by 1970.

Newark’s industrial boom attracted enterprising inventors like Thomas Edison, who created the ticker tape machine while in Newark. Seth Boyden invented the process for making patent leather and malleable iron, in addition to developing a hat-forming machine and an inexpensive process for manufacturing sheet iron. John W. Hyatt developed celluloid (for camera film), which he went into the business of selling with his brothers in 1872. D. Edward Weston’s Weston Electrical Instrument Company created the

Weston standard cell, the first accurate portable voltmeters and ammeters, the first portable lightmeter, and many other electrical developments. Such developments helped the city enter early into the manufacture of plastics, electrical goods, and chemicals.

Some attribute Newark’s downfall to its propensity for building large housing projects. Newark’s housing had long been a matter of concern, as much of it was older. A 1944 city-commissioned study showed that 31 percent of all Newark dwelling units were below standards of health, and only 17 percent of Newark’s units were owner-occupied. Vast sections of Newark consisted of wooden tenements, and at least 5,000 units failed to meet thresholds of being a decent place to live. Bad housing was the cause of demands that government intervene in the housing market to improve conditions.

Historian Kenneth T. Jackson and others theorized that Newark, with a poor center surrounded by middle-class outlying areas, only did well when it was able to annex middle-class suburbs. When municipal annexation broke down, urban problems were exacerbated as the middle-class ring became divorced from the poor center. In 1900, Newark’s mayor had confidently speculated, “East Orange,Vailsburg, Harrison, Kearny, and Belleville would be desirable acquisitions. By an exercise of discretion we can enlarge the city from decade to decade without unnecessarily taxing the property within our limits, which has already paid the cost of public improvements.” Only Vailsburg would ever be added.

Although numerous problems predated World War II, Newark was more hamstrung by a number of trends in the post-WWII era. The Federal Housing Administration redlined virtually all of Newark, preferring to back up mortgages in the white suburbs. This made it impossible for people to get mortgages for purchase or loans for improvements. Manufacturers set up in lower wage environments outside the city and received larger tax deductions for building new factories in outlying areas than for rehabilitating old factories in the city. The federal tax structure essentially subsidized such inequities.

Billed as transportation improvements, construction of new highways: Interstate 280, the New Jersey Turnpike, and Interstate 78 harmed Newark. They directly hurt the city by dividing the fabric of neighborhoods and displacing many residents. The highways indirectly hurt the city because the new infrastructure made it easier for middle-class workers to live in the suburbs and commute into the city.

Despite its problems, Newark tried to remain vital in the postwar era. The city successfully persuaded Prudential and Mutual Benefit to stay and build new offices. Rutgers University-Newark, New Jersey Institute of Technology, and Seton Hall University expanded their Newark presences, with the former building a brand-new campus on a 23 acre (9 hectare) urban renewal site. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey made Port Newark the first container port in the nation. South of the city, during the postwar era, it took over operations at Newark Liberty International Airport, now the thirteenth busiest airport in the United States.

The tallest buildings in downtown Newark: 1180 Raymond, 740 Broad St., and Prudential Insurance Headquarters.

The tallest buildings in downtown Newark: 1180 Raymond, 740 Broad St., and Prudential Insurance Headquarters.

The city made serious mistakes with public housing and urban renewal, although these were not the sole causes of Newark’s tragedy. Across several administrations, the city leaders of Newark considered the federal government’s offer to pay for 100% of the costs of housing projects as a blessing. The decline in industrial jobs meant that more poor people needed housing, whereas in prewar years, public housing was for working-class families. While other cities were skeptical about putting so many poor families together and were cautious in building housing projects, Newark pursued federal funds. Eventually, Newark had a higher percentage of its residents in public housing than any other American city.

The largely Italian-American First Ward was one of the hardest hit by urban renewal. A 46 acre (19 hectare) housing tract, labeled a slum because it had dense older housing, was torn down for multi-story, multi-racial Le Corbusier-style high rises, named the Christopher Columbus Homes. The tract had contained 8th Avenue, the commercial heart of the neighborhood. Fifteen small-scale blocks were combined into three “superblocks.” The Columbus Homes, never in harmony with the rest of the neighborhood, were vacated in the 1980’s. They were finally torn down in 1994. For more information go to the link at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Newark,_New_Jersey.

The 1976 Riots:

Two years after the infamous 1965 riots in Watts, Los Angeles, racial tension erupted in violence in Cincinnati, Cleveland, Washington D.C. – over all, 125 cities experienced riots in 1967. The two most well-known and destructive uprisings occurred in Detroit and Newark.

Two years after the infamous 1965 riots in Watts, Los Angeles, racial tension erupted in violence in Cincinnati, Cleveland, Washington D.C. – over all, 125 cities experienced riots in 1967. The two most well-known and destructive uprisings occurred in Detroit and Newark.

Naturally, this violence can’t be blamed on a heat wave, but the uncomfortable weather that summer undoubtedly played a part in amplifying the community’s already high-pitched tensions. Housing segregation, which had begun when African Americans started moving to Newark in 1870, had concentrated Newark’s African American community into one of the country’s poorest ghettos. In 1967, Newark had the nation’s highest percentage of substandard housing, and the second highest rates of crime and infant mortality. That July, purported police brutality involving the arrest of an African American cab driver charged with assaulting a police officer plunged the city into four days of violence and destruction.

Although deteriorated housing, high unemployment, inferior schools, a corrupt municipal government, and a lack of political power set the scene for the violence of ’67, two issues that summer had particularly elevated Newark’s racial tension. One involved the mayor’s selection for the position of secretary of the school board, a matter that nearly caused a fight between blacks and whites at a June meeting. The other regarded the city’s plans to construct the New Jersey College of Medicine and Dentistry on a 50-acre plot in the Central Ward that the African American community felt should be used for housing.

The riots began as a crowd of around 200 assembled outside the Fourth Precinct station house to protest the arrest of the cab driver with chants of “police brutality.” Rocks and bottles were thrown, and the crowd was eventually dispersed. Yet, that night bands of angry looters caroused through the city, smashing windows (mostly of liquor stores), strewing merchandise in the streets, and pulling fire alarms.

The following day the violence moved into Newark’s business district, and the mayor called for support from the National Guard and state troopers. Fires sprang up all over the city. On the third day, National Guardsmen and state troopers opened fire on rioters. African American business owners started writing “soul bro” on their storefronts in the hope of preventing looting.

The four-day riot left 26 people dead – including 10-year-old Edward Moss. Over 1,000 were injured, and the city incurred more than $10 million in property damaged.

Written by: David Hartman and Historian Barry Lewis & Educational Broadcasting Corporation, 2002