#47. Monticello

Monticello: Thomas Jefferson’s World

Thomas Jefferson’s World illustrates how Jefferson’s vision for America and his optimism about the future were driven by his fundamental beliefs in human rights, personal freedom, and democratic values. Jefferson’s crucial role in America’s revolutionary struggle for independence, his political career, his varied interests, and the conflict in his championing liberty while owning slaves all are explored.

Monticello, Location: Charlottesville, Virginia, Architect: Thomas Jefferson Year: 1772

Monticello, Location: Charlottesville, Virginia, Architect: Thomas Jefferson Year: 1772

It is easy to forget that Thomas Jefferson, chief architect of the United States Constitution, is also responsible for the pinnacle of Neoclassical architecture in America. His own home, Monticello, was built on the principals of Italian renaissance architect Andrea Palladio and named a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1987.

Albemarle County, near Charlottesville, Virginia, USA

Albemarle County, near Charlottesville, Virginia, USA

Monticello was the primary plantation of Thomas Jefferson, the third President of the United States, who, after inheriting quite a large amount of land from his father, started building Monticello when he was twenty-six years old. Located just outside Charlottesville, Virginia, in the Piedmont region, the plantation was originally 5,000 acres (2,000 ha), with extensive cultivation of tobacco and mixed crops, with labor by slaves. What started as a mainly tobacco plantation switched over to a wheat plantation later in Jefferson’s life.

The house, which Jefferson designed, was based on the neoclassical principles described in the books of the Italian Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio. He reworked it through much of his presidency to include design elements popular in late eighteenth-century Europe. It contains many of his own design solutions. The house is situated on the summit of an 850-foot (260 m)-high peak in the Southwest Mountains south of the Rivanna Gap. Its name comes from the Italian “little mount.” The plantation at full operations included numerous outbuildings for specialized functions, a nailery, and quarters for domestic slaves along Mulberry Row near the house; gardens for flowers, produce, and Jefferson’s experiments in plant breeding; plus tobacco fields and mixed crops. Cabins for field slaves were located further from the mansion.

At Jefferson’s direction, he was buried on the grounds, an area now designated as the Monticello Cemetery, which is owned by the Monticello Association, a lineage society of his descendants through Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson. After Jefferson’s death, his daughter Martha Jefferson Randolph sold the property. After other owners, in 1834 it was bought by Uriah P. Levy, a commodore in the U.S. Navy, who admired Jefferson and spent his own money to preserve the property. His nephew Jefferson Monroe Levy took over the property in 1879; he also invested considerable money to restore and preserve it. He held it until 1923, when he sold it to the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, which operates it as a house museum and educational institution. It has been designated a National Historic Landmark. In 1987 Monticello and the nearby University of Virginia, also designed by Jefferson, were together designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Design and building

Jefferson’s home was built to serve as a plantation house, which ultimately took on the architectural form of a villa. It has many architectural antecedents but Jefferson went beyond them to create something very much his own. He consciously sought to create a new architecture for a new nation.

Work began on what historians would subsequently refer to as “the first Monticello” in 1768, on a plantation of 5,000 acres (2,000 hectares). Jefferson moved into the South Pavilion (an outbuilding) in 1770, where his new wife Martha Wayles Skelton joined him in 1772. Jefferson continued work on his original design, but how much was completed is of some dispute.

After his wife’s death in 1782, Jefferson left Monticello in 1784 to serve as Minister of the United States to France. During his several years’ in Europe, he had an opportunity to see some of the classical buildings with which he had become acquainted from his reading, as well as to discover the “modern” trends in French architecture that were then fashionable in Paris. His decision to remodel his own home may date from this period. In 1794, following his service as the first U.S. Secretary of State (1790–93), Jefferson began rebuilding his house based on the ideas he had acquired in Europe. The remodeling continued throughout most of his presidency (1801–09). Although generally completed by 1809, Jefferson continued work on the present structure until his death in 1826.

Some of the gardens on the property

Some of the gardens on the property

Jefferson added a center hallway and a parallel set of rooms to the structure, more than doubling its area. He removed the second full-height story from the original house and replaced it with a mezzanine bedroom floor. The interior is centered on two large rooms, which served as an entrance-hall-museum, where Jefferson displayed his scientific interests, and a music-sitting room. The most dramatic element of the new design was an octagonal dome, which he placed above the west front of the building in place of a second-story portico. The room inside the dome was described by a visitor as “a noble and beautiful apartment,” but it was rarely used—perhaps because it was hot in summer and cold in winter, or because it could only be reached by climbing a steep and very narrow flight of stairs. The dome room has now been restored to its appearance during Jefferson’s lifetime, with “Mars yellow” walls and a painted green floor.

History

After Jefferson died on July 4, 1826, his only surviving daughter Martha Jefferson Randolph inherited Monticello. The estate was encumbered with debt and Martha Randolph had financial problems in her own family because of her husband’s mental illness. In 1831 she sold Monticello to James Turner Barclay, a local apothecary. Barclay sold it in 1834 to Uriah P. Levy, the first Jewish Commodore (equivalent to today’s admiral) in the United States Navy. A fifth-generation American whose family first settled inSavannah, Georgia, Levy greatly admired Jefferson. He used his private funds to repair, restore and preserve the house. During the American Civil War, the house was seized by the Confederate government because it was owned by a Northern officer and sold. Uriah Levy’s estate recovered the property after the war.

Levy’s heirs argued over his estate, but their lawsuits were settled in 1879, when Uriah Levy’s nephew, Jefferson Monroe Levy, a prominent New York lawyer, real estate and stock speculator and member of Congress, bought out the other heirs for $10,050, and took control of the property. Like his uncle, Jefferson Levy commissioned repairs, restoration and preservation at Monticello, which had been deteriorating seriously while the lawsuits wound their way through the courts in New York and Virginia. Together, the Levys preserved Monticello for the American people for nearly 100 years.

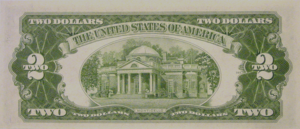

Monticello depicted on the reverse of the 1953 $2 bill. Note the two “Levy lions” on either side of the entrance. The lions, placed there by Jefferson Levy, were removed in 1923 when the Thomas Jefferson Foundation purchased the house.

Monticello depicted on the reverse of the 1953 $2 bill. Note the two “Levy lions” on either side of the entrance. The lions, placed there by Jefferson Levy, were removed in 1923 when the Thomas Jefferson Foundation purchased the house.

In 1923, a private non-profit organization, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, purchased the house from Jefferson Levy with funds raised by Theodore Fred Kuper and others. They managed additional restoration under architects including Fiske Kimball and Milton L. Grigg. Since that time, other restoration has been done at Monticello.

The Foundation operates Monticello and its grounds as a house museum and educational institution. Visitors can view rooms in the cellar and ground floor, but the second and third floors are not open to the general public due to fire code restrictions. Visitors can tour the third floor (Dome), while on a Signature Tour.

Monticello is a National Historic Landmark. It is the only private home in the United States to be designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Included in that designation are the original grounds and buildings of Jefferson’s University of Virginia. From 1989 to 1992, a team of architects from the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) of the United States created a collection of measured drawings of Monticello. These drawings are held by the Library of Congress.

Among Jefferson’s other designs are Poplar Forest, his private retreat near Lynchburg, which he intended for his daughter Maria, who died at age 25; the University of Virginia, and the Virginia State Capitol in Richmond.