#46. The Queen’s House

The Queen’s Palaces – Buckingham Palace

The Queen has three official residences – the best known, Buckingham Palace; the oldest, Windsor Castle; and the most romantic, Palace of Holyroodhouse. Among the few working royal palaces in the world today, they serve as both family homes and as the setting for the business of Monarchy. Each has its own distinctive story – long histories that reflect good and bad times, triumph and tragedy and, of course, the lives of some of our most memorable kings and queens. But they all share certain features – incredible collections of treasures that reflect both the tastes of their occupants and the artistic development of the nation, and architecture that has evolved across the centuries to meet the needs of different ages, reflecting the story of Britain and its people like no other buildings. Buckingham Palace may be just about the most famous building in the world, but its story is much less familiar. Fiona Bruce reveals how England’s most spectacular palace emerged from a swampy backwater in just 300 years. The journey of discovery takes her from the sewers of London to the magnificent State Rooms; from a home for camels and elephants to the artistic brilliance of C18th-century Venice; and from a prince’s Chinese fantasy to the secret of how the Palace’s glittering chandeliers are cleaned today.

The Queen’s House, Location: Greenwich, London, Architect: Inigo Jones Year: 1632

The Queen’s House, Location: Greenwich, London, Architect: Inigo Jones Year: 1632

Inigo Jones, the first significant English architect of the modern era, is not surprisingly responsible for the first consciously classical building in Britain. That building is, as you’d guess, the Queen’s House, and it came early in Jones’ career and for a rather important client – Anne of Denmark, the Queen of King James I. To his credit, Jones used the building to introduce Palladianism to the English, his building appearing in their eyes “radical.” Since completion in 1632, the building has housed a series of important people and objects (it stands now as part of the Royal Maritime Museum). If your are very important you may find yourself in the Queen’s House during the 2012 London Olympics – the building has been designated the VIP center.

The Queen’s House, viewed from the main gate

The Queen’s House, viewed from the main gate

The Queen’s House, Greenwich, is a former royal residence built between 1616–1619 in Greenwich, then a few miles downriver from London, and now a district of the city. Its architect was Inigo Jones, for whom it was a crucial early commission, for Anne of Denmark, the queen of King James I of England. It was altered and completed by Jones, in a second campaign about 1635 for Henrietta Maria, queen of King Charles I. The Queen’s House is one of the most important buildings in British architectural history, being the first consciously classical building to have been constructed in Britain. It was Jones’s first major commission after returning from his 1613–1615 grand tour of Roman, Renaissance and Palladian architecture in Italy.

Some earlier English buildings, such as Longleat, had made borrowings from the classical style; but these were restricted to small details and were not applied in a systematic way. Nor was the form of these buildings informed by an understanding of classical precedents. The Queen’s House would have appeared revolutionary to English eyes in its day. Jones is credited with the introduction of Palladianism with the construction of the Queen’s House, although it diverges from the mathematical constraints of Palladio and it is likely that the immediate precedent for the H shaped plan straddling a road is the Villa Medici at Poggio a Caianoby Giuliano da Sangallo. Today it is both a grade I listed building and a Scheduled ancient monument, a status which includes the 115-foot-wide (35 m), axial vista to the River Thames. The house now forms part of the National Maritime Museum and is used to display parts of their substantial collection of maritime paintings and portraits. It was used as a VIP centre in the 2012 Olympic games.

Early History

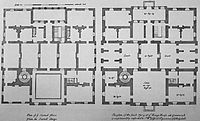

Plans of the Queen’s House. The salon is a 40-foot (12.2 m) cube.

Plans of the Queen’s House. The salon is a 40-foot (12.2 m) cube.

The Queen’s House is located in Greenwich, London, England. It was built as an adjunct to the Tudor Palace of Greenwich, previously known, before its redevelopment by Henry VII as the Palace of Placentia, which was a rambling, mainly red-brick building in a more vernacular style. This would have presented a dramatic contrast of appearance to the newer, white-painted House, although the latter was much smaller and really a modern version of an older tradition of private ‘garden houses’, not a public building, and one used only by the queen’s privileged inner circle. However, the House’s original use was short – no more than seven years – before the English Civil War began in 1642 and swept away the court culture from which it sprang. Of its interiors, three ceilings and some wall decorations survive in part, but no interior remains in its original state. This process began as early as 1662, when masons removed a niche and term figures and a chimneypiece.

Paintings commissioned by Charles I for the house from Orazio Gentileschi, but now elsewhere, include a ceiling Allegory of Peace and the Arts, now installed at Marlborough House, London, a large Finding of Moses, now on loan from a private collection to the National Gallery, London, and a matching Joseph and Potiphar‘s Wife still in the Royal Collection.

The Queen’s House, though it was scarcely being used, provided the distant focal centre for Sir Christopher Wren‘s Greenwich Hospital, with a logic and grandeur that has seemed inevitable to architectural historians but in fact depended on Mary II‘s insistence that the vista to the water from the Queen’s House not be impaired.

Construction of the Greenwich Hospital

Although the House survived as an official building—being used for the lying-in-state of Commonwealth Generals-at-Sea Richard Dean (1653) and Robert Blake (1657)—the main palace was progressively demolished from the 1660s to 1690s and replaced by the Royal Hospital for Seamen, built 1696–1751 to the master-plan of Sir Christopher Wren. This is now called the Old Royal Naval College, after its later use from 1873 to 1998. The position of the House, and Queen Mary II‘s order that it retain its view to the river (only gained on demolition of the older Palace), dictated Wren’s Hospital design of two matching pairs of ‘courts’ separated by a grand ‘visto’ exactly the width of the House (115 ft). The whole forms an impressive architectural ensemble that stretches from the Thames to Greenwich Park and is one of the principal features that in 1997 led UNESCO to inscribe ‘Maritime Greenwich’ as a World Heritage Site.

The Queen’s House viewed from the foot of Observatory Hill, showing the original house (1635) and the additional wings linked by colonnades (1807)

The Queen’s House viewed from the foot of Observatory Hill, showing the original house (1635) and the additional wings linked by colonnades (1807)

19th Century additions

From 1806 the House itself was the centre of what, from 1892, became the Royal Hospital School for the sons of seamen. This necessitated new accommodation wings, and a flanking pair to east and west were added and connected to the House by colonnades from 1807 (designed by London Docks architect Daniel Asher Alexander), with further surviving extensions up to 1876. In 1933 the school moved to Holbrook, Suffolk. Its Greenwich buildings, including the House, were converted and restored to become the new National Maritime Museum (NMM), created by Act of Parliament in 1934 and opened in 1937.

The grounds immediately to the north of the House were reinstated in the late 1870s following construction of the cut-and-cover tunnel between Greenwich and Maze Hill stations. The tunnel comprised the continuation of the London and Greenwich Railway and opened in 1878.

The Tulip Stairs and lantern from below; the first centrally unsupported helical stairs constructed in England. The stairs are supported by a combination of support by cantilever from the walls and each tread resting on the one below.

The Tulip Stairs and lantern from below; the first centrally unsupported helical stairs constructed in England. The stairs are supported by a combination of support by cantilever from the walls and each tread resting on the one below.

Recent years

The House was further restored between 1986 and 1999, not always sympathetically: an editorial in The Burlington Magazine, November 1995, alluded to “the recent transformation of the Queen’s House into a theme-park interior of fake furniture and fireplaces, tatty modern plaster casts and clip-on chandeliers.” It is now largely used to display the Museum’s substantial collection of marine paintings and portraits of the 17th to 20th centuries, and for other public and private events. It is normally open to the public daily, free of charge, along with the other museum galleries and the 17th-century Royal Observatory, Greenwich, which is also part of the National Maritime Museum.

The “Queen’s House” was also the name used for Buckingham House, later to be rebuilt asBuckingham Palace, when it was Queen Charlotte‘s residence during the reign of George III.

London Olympic Games, 2012

The grounds behind the Queen’s House were used to house a stadium for the equestrian events of the Olympic Games in 2012. The modern pentathlon was also staged in the grounds of Greenwich Park. The Queen’s House itself was used as a VIP centre for the games. Work to prepare the Queen’s House involved some internal re-modelling and work on the lead roof to prepare it for security and camera installations.