50th Anniversary of the 1964 New York World’s Fair

Defunctland: The History of the 1964 New York World’s Fair

Extinct Attractions 1964 Worlds Fair part 1 by David Oneal.

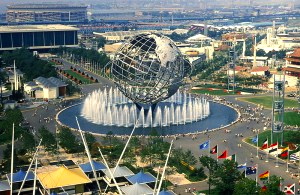

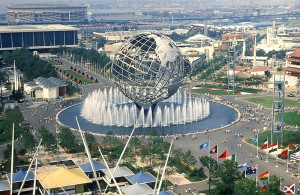

View from the observation towers of the New York State Pavilion; the Unisphere is in the center, Shea Stadium at far background left.

View from the observation towers of the New York State Pavilion; the Unisphere is in the center, Shea Stadium at far background left.

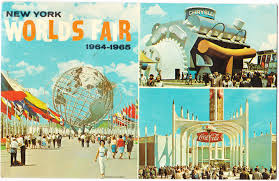

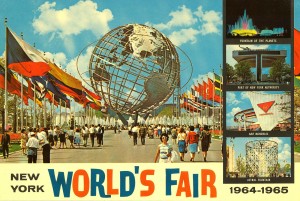

The 1964/1965 New York World’s Fair was the third major world’s fair to be held in New York City. Hailing itself as a “universal and international” exposition, the fair’s theme was “Peace Through Understanding”, dedicated to “Man’s Achievement on a Shrinking Globe in an Expanding Universe”; American companies dominated the exposition as exhibitors. The theme was symbolized by a 12-story high, stainless-steel model of the earth called the Unisphere. The fair ran for two six-month seasons, April 22 – October 18, 1964 and April 21 – October 17, 1965. Admission price for adults (13 and older) was $2 in 1964 (about $15 in 2013 dollars) but $2.50 in 1965, and $1 for children (2–12) both years (about $7 in 2013 dollars).

The fair is best remembered as a showcase of mid-20th-century American culture and technology. The nascent Space Age, with its vista of promise, was well represented. More than 51 million people attended the fair, though less than the hoped-for 70 million. It remains a touchstone for New York–area Baby Boomers, who visited the optimistic fair as children before the turbulent years of the Vietnam War, cultural changes, and increasing struggles for civil rights.

In many ways the fair symbolized a grand consumer show covering many products produced in America at the time for transportation, living, and consumer electronic needs in a way that would never be repeated at future world’s fairs in North America. Most American companies from pen manufacturers to auto companies had a major presence. While this fair did not receive official sanctioning from the Bureau of International Expositions (BIE), it did give many attendees their first interaction with computer equipment. Many corporations demonstrated the use of mainframe computers, computer terminals with keyboards and CRT displays, Teletype machines, punch cards, and telephone modems in an era when computer equipment was kept in back offices away from the public, decades before the Internet and home computers were at everyone’s disposal.

Historical Antecedents

The site, Flushing Meadows Corona Park in the borough of Queens, had also held the 1939/1940 New York World’s Fair. It was one of the largest world’s fairs to be held in the United States, occupying nearly a square mile (2.6 km2) of land. The only larger fair was the 1939 fair, which occupied space that was filled in for the 1964/1965 exposition. Preceding these fairs was the 1853–54 New York’s World’s Fair, called the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations, located in the New York Crystal Palace on what is now Bryant Park in the borough of Manhattan, New York City (All three of New York’s world’s fairs were the only international expositions to run for two years, rather than one).

The site, Flushing Meadows Corona Park in the borough of Queens, had also held the 1939/1940 New York World’s Fair. It was one of the largest world’s fairs to be held in the United States, occupying nearly a square mile (2.6 km2) of land. The only larger fair was the 1939 fair, which occupied space that was filled in for the 1964/1965 exposition. Preceding these fairs was the 1853–54 New York’s World’s Fair, called the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations, located in the New York Crystal Palace on what is now Bryant Park in the borough of Manhattan, New York City (All three of New York’s world’s fairs were the only international expositions to run for two years, rather than one).

Controversial Beginnings

The 1964/1965 Fair was conceived by a group of New York businessmen who fondly remembered their childhood experiences at the 1939 New York World’s Fair and wanted to provide that same experience for their children and grandchildren. Thoughts of an economic boom to the city as the result of increased tourism was also a major reason for holding another fair 25 years after the 1939/1940 extravaganza. Then-New York City mayor, Robert F. Wagner, Jr., commissioned Frederick Pittera, a producer of international fairs and exhibitions, and author of the history of International Fairs & Exhibitions for the Encyclopaedia Britannica and Compton’s Encyclopedia, to prepare the first feasibility studies for the 1964/1965 New York World’s Fair. He was joined by Austrian architect Victor Gruen (creator of the shopping mall) in studies that eventually led the Eisenhower Commission to award the world’s fair to New York City in competition with a number of American cities.

Organizers turned to private financing and the sale of bonds to pay the huge costs to stage them. The organizers hired New York’s “Master Builder” Robert Moses, to head the corporation established to run the fair because he was experienced in raising money for vast public projects. Moses had been a formidable figure in the city since coming to power in the 1930’s. He was responsible for the construction of much of the city’s highway infrastructure and, as parks commissioner for decades, the creation of much of the city’s park system.

Organizers turned to private financing and the sale of bonds to pay the huge costs to stage them. The organizers hired New York’s “Master Builder” Robert Moses, to head the corporation established to run the fair because he was experienced in raising money for vast public projects. Moses had been a formidable figure in the city since coming to power in the 1930’s. He was responsible for the construction of much of the city’s highway infrastructure and, as parks commissioner for decades, the creation of much of the city’s park system.

In the mid-1930’s, Moses oversaw the conversion of a vast Queens tidal marsh/garbage dump into the fairgrounds that hosted the 1939/1940 World’s Fair. Called Flushing Meadows Park, it was Moses’ grandest park scheme. He envisioned this vast park, comprising some 1,300 acres (5 km2) of land, easily accessible from Manhattan, as a major recreational playground for New Yorkers. When the 1939/1940 World’s Fair ended in financial failure, Moses did not have the available funds to complete work on his project. He saw the 1964/1965 Fair as a means to finish what the earlier fair had begun.

To ensure profits to complete the park, fair organizers knew they would have to maximize receipts. An attendance of 70 million people would be needed to turn a profit and, for attendance that large, the fair would need to be held for two years. The World’s Fair Corporation also decided to charge site rental fees to all exhibitors who wished to construct pavilions on the grounds. This decision caused the fair to come into conflict with the Bureau of International Expositions (BIE), the international body headquartered in Paris that sanctions world’s fairs: BIE rules stated that an international exposition could run for one six-month period only, and no rent could be charged to exhibitors. In addition, the rules allowed only one exposition in any given country within a 10-year period, and the Seattle World’s Fair had already been sanctioned for 1962.

The United States was not a member of the BIE at the time, but fair organizers understood that a sanction by the BIE would assure that its nearly 40 member nations would participate in the fair. Moses, undaunted by the rules, journeyed to Paris to seek official approval for the New York fair. When the BIE balked at New York’s bid, Moses, used to having his way in New York, angered the BIE delegates by taking his case to the press, publicly stating his disdain for the BIE and its rules. The BIE retaliated by formally requesting its member nations not to participate in the New York fair. The 1939/1940 and 1964/1965 New York World’s Fairs were the only significant world’s fairs since the formation of the BIE to be held without its endorsement.

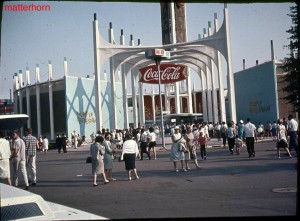

Architecture

Many of the pavilions were built in a Mid-Century modern style that was heavily influenced by “Googie architecture“. This was a futurist architectural style influenced by car culture, jet aircraft, the Space Age, and the Atomic Age, which were all on display at the fair. Some pavilions were explicitly shaped like the product they were promoting, such as the US Royaltire-shaped Ferris wheel, or even the corporate logo, such as the Johnson Wax pavilion. Other pavilions were more abstract representations, such as the prolate spheroid shaped IBM pavilion, or the General Electric circular dome shaped “Carousel of Progress.”

Many of the pavilions were built in a Mid-Century modern style that was heavily influenced by “Googie architecture“. This was a futurist architectural style influenced by car culture, jet aircraft, the Space Age, and the Atomic Age, which were all on display at the fair. Some pavilions were explicitly shaped like the product they were promoting, such as the US Royaltire-shaped Ferris wheel, or even the corporate logo, such as the Johnson Wax pavilion. Other pavilions were more abstract representations, such as the prolate spheroid shaped IBM pavilion, or the General Electric circular dome shaped “Carousel of Progress.”

The pavilion architectures often expressed a new-found freedom of form enabled by modern building materials, such as reinforced concrete, fiberglass, plastic, tempered glass, and stainless steel. The facade or the entire structure of a pavilion served as a giant billboard advertising the country or organization housed inside, flamboyantly competing for the attention of busy and distracted fairgoers.

By contrast, some of the smaller international, US state, and organizational pavilions were built in more traditional styles, such as a Swiss chalet or a Chinese temple. After the fair’s final closing in 1965, some pavilions crafted of wood were carefully disassembled and transported elsewhere for re-use.

Other pavilions were “decorated sheds”, a building method described by Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, using plain structural shells embellished with applied decorations. This allowed designers to simulate a traditional style while bypassing expensive and time-consuming methods of traditional construction. The expedient was considered acceptable for temporary buildings planned to be used for only two years, and then to be demolished.

International Participation

View of the Unisphere with world flags

View of the Unisphere with world flags

The BIE rejection was nearly a disaster for the fair. The absence of Canada, Australia, most of the major European nations and the Soviet Union, all members of the BIE, tarnished the image of the fair. Additionally, New York was forced to compete with both Seattle and Montreal for international participants, with many nations choosing the officially sanctioned world’s fairs of those cities over the New York Fair. The fair turned to trade and tourism organizations within many countries to sponsor national exhibits in lieu of official government sponsorship of pavilions.

New York City, in the middle of the 20th century, was at a zenith of economic power and world prestige. Unconcerned by BIE rules, nations with smaller economies (as well as private groups in (or relevant to) some BIE members) saw it as an honor to host an exhibit at the Fair. Therefore smaller nations made up the majority of the international participation. Spain, Vatican City, Japan, Mexico, Sweden, Austria, Denmark, Thailand, Philippines, Greece, and Pakistan, and Ireland to name some, hosted national presences at the Fair. Indonesia sponsored a pavilion, but relations deteriorated rapidly between that nation and the USA during 1964, fueled by anti-Western and anti-American rhetoric and policies by Indonesian president Sukarno, which angered US President Lyndon Baines Johnson. Indonesia withdrew from the United Nations in January 1965, and officially from the Fair in March. The Fair Corporation then seized and shut down the Indonesian pavilion, and it remained closed and barricaded for the 1965 season.

One of the fair’s most popular exhibits was the Vatican Pavilion, where Michelangelo‘s Pietà was displayed; a small plaza marking the spot (and Pope Paul VI‘s visit in October 1965) remains there today. A modern copy had been transported beforehand to ensure that the statue could be conveyed without being damaged. This copy is now on view at St. Joseph’s Seminary, Dunwoodie, in Yonkers.

A recreation of a medieval Belgian village proved very popular. Fairgoers were treated to the “Bel-Gem Brussels Waffle”—a combination of waffle, strawberries and whipped cream, sold by a Brussels couple, Maurice Vermersch and his wife.

Fairgoers could also enjoy sampling sandwiches from around the world at the popular Seven Up International Gardens Pavilion which featured the innovative fiberglass Seven Up Tower. While dining, visitors were treated to live performances of international music by the 7-Up Continental Band as well as musical selections from the Broadway stage.

Emerging African nations displayed their wares in the Africa Pavilion. Controversy broke out when the Jordanian pavilion displayed a mural emphasizing the plight of the Palestinian people. The Jordanians also donated an ancient column which remains at their former site. The city of West Berlin, a Cold War hot-spot, hosted a popular display.

Federal and State Exhibits – US Pavilion

The US Pavilion was titled “Challenge to Greatness” and focused on President Lyndon B. Johnson‘s “Great Society” proposals. The main show in the multi-million dollar pavilion was a 15-minute ride through a filmed presentation of American history. Visitors seated in moving grandstands rode past movie screens that slid in, out and over the path of the traveling audience. Elsewhere, there were tributes to President John F. Kennedy, who had broken ground for the pavilion in December 1962 but had been assassinated in November 1963 before the fair opened.

The US Pavilion was titled “Challenge to Greatness” and focused on President Lyndon B. Johnson‘s “Great Society” proposals. The main show in the multi-million dollar pavilion was a 15-minute ride through a filmed presentation of American history. Visitors seated in moving grandstands rode past movie screens that slid in, out and over the path of the traveling audience. Elsewhere, there were tributes to President John F. Kennedy, who had broken ground for the pavilion in December 1962 but had been assassinated in November 1963 before the fair opened.

United States Space Park

A 2-acre (8,100 m2) United States Space Park was sponsored by NASA, the Department of Defense and the fair. Exhibits included a full-scale model of the aft skirt and five F-1 engines of the first stage of a Saturn V, a Titan II booster with a Gemini capsule, an Atlas with a Mercury capsule and a Thor-Delta rocket. On display at ground level were Aurora 7, the Mercury capsule flown on the second US manned orbital flight; full-scale models of an X-15 aircraft, an Agena upper stage; a Gemini spacecraft; an Apollo command/service module, and a Lunar Excursion Module. Replicas of unmanned spacecraft included lunar probe Ranger VII; Mariner II and Mariner IV; Syncom, Telstar I, and Echo II communications satellites; Explorer I and Explorer XVI; and Tiros and Nimbus weather satellites.

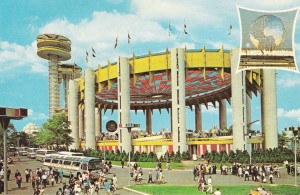

New York State Pavilion

New York State played host to the fair at its six-million-dollar open-air pavilion called the “Tent of Tomorrow.” Designed by famed modernist architect Philip Johnson, the 350-foot-by-250-foot pavilion was supported by sixteen 100-foot-high concrete columns, from which a 50,000-square-foot roof of polychrome tiles was suspended. Complementing the pavilion were the fair’s three high-spot observation towers, two of which had cafeterias in their in-the-round observation-deck crowns. The pavilion’s main floor, used for local art and industry displays including a 26-foot scale reproduction of the New York State Power Authority‘s St. Lawrence hydroelectric plant, comprised a 9,000-square-foot terrazzo replica of the official Texaco highway map of New York State, displaying the map’s cities, towns, routes and Texaco gas stations in 567 mosaic panels. An idea floated after the fair to use the floor for the World Trade Center did not materialize.

Wisconsin exhibited the “World’s Largest Cheese.” Florida brought a dolphin show, flamingos, a talented cockatoo from Miami‘s Parrot Jungle, and water skiers to New York. Oklahoma gave weary fairgoers a restful park to relax in. Missouri displayed the state’s space-related industries. Visitors could dine at Hawaii‘s “Five Volcanoes” restaurant.

New York City Pavilion

At the New York City pavilion, the “Panorama of the City of New York“, a huge scale model of the City was on display, complete with a simulated helicopter ride around the metropolis for easy viewing. Left over from the 1939 Fair, this building had also hosted the United Nations from 1947 to 1952.

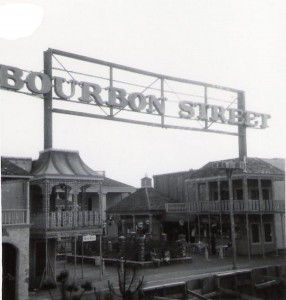

Louisiana had a pavilion called “Louisiana’s Bourbon Street” (later renamed to just “Bourbon Street”), which was inspired by New Orleans’ French Quarter. It started off with financial trouble, not being able to complete its construction and subsequently filing for bankruptcy. A private company, called Pavilion Property, bought up the assets and assumed its debts. This prompted Louisiana GovernorJohn McKeithen to sever all ties and withdraw state’s sanction, leaving the pavilion completely to private enterprise.

Special media attention was given to a racially integrated minstrel show, that was intended to be satirical anti-bigotry, called “America, Be Seated”, produced by Mike Todd Jr. During the opening of the fair, several civil rights protests were staged by members of the NAACP, who believed that the “minstrel-style” show was demeaning to African Americans.

The pavilion included ten theater restaurants, which served a variety of Creole food, a Jazz club called “Jazzland” which hosted live jazz artists, miniature Mardi Gras parades, a teenage dancing venue, a voodoo shop, and a doll museum. Due to the presence of the various bars, the pavilion was especially popular at night. Notable go-go dancer Candy Johnson headlined a show at a venue called “Gay New Orleans Nightclub”. Near the closure of the fair, the pavilion was reported to have achieved the highest gross income of any single commercial pavilion at the fair. The 26-year-old director of operations, Gordon Novel, was called an “Entrepreneurial Prodigy & Boy Wonder” in Variety for his accomplishments.

American industry in the spotlight

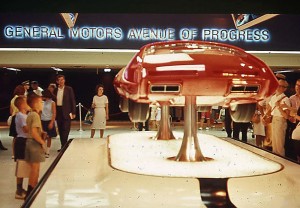

Concept car inside the General Motors Pavilion

Concept car inside the General Motors Pavilion

At the New York World’s Fair of 1939/1940, industrial exhibitors played a major role by hosting huge, elaborate exhibits. Many of them returned to the New York World’s Fair of 1964/1965 with even more elaborate versions of the shows they had presented 25 years earlier. The most notable of these was General Motors Corporation whose Futurama, a show in which visitors seated in moving chairs glided past elaborately detailed miniature 3D model scenery showing what life might be like in the “near-future”, proved to be the fair’s most popular exhibit. Nearly 26 million people took the journey into the future during the fair’s two-year run.

IBM Pavilion

The IBM Corporation had a popular pavilion, where a giant 500-seat grandstand called the “People Wall” was pushed by hydraulic rams high up into an ellipsoidal theater designed by Eero Saarinen. There, a film by Charles and Ray Eamestitled Think was shown on fourteen large and eight small screens, illuminating the workings of computer logic. At ground level beneath the theater, visitors could explore Mathematica: A World of Numbers… and Beyond (an exhibit of mathematical models and curiosities) and view the Mathematics Peep Show (a series of short films illustrating basic mathematical concepts). IBM also demonstrated handwriting recognition on a mainframe computer that would look up what happened on a particular date that a person wrote down—for many visitors, this was their first hands-on interaction with a computer.

Bell System Pavilion

The Bell System (prior to its break up into regional companies) hosted a 15-minute ride in moving armchairs depicting the history of communications in dioramas and film. Other Bell exhibits included the Picturephone as well as a demonstration of the computer modem. DuPont presented a musical review by composer Michael Brown called “The Wonderful World of Chemistry”. At Parker Pen‘s exhibit, a computer would make a match to an international penpal.

The Westinghouse Corporation planted a second time capsule next to the 1939 one; today both Westinghouse Time Capsules are marked by a monument southwest of the Unisphere which is to be opened in the year 6939. Some of its contents were a World’s Fair Guidebook, an electric toothbrush, credit cards(relatively new at the time) and a 50-star United States flag.

Dinoland

The Sinclair Oil Corporation sponsored “Dinoland”, featuring life-size replicas of nine different dinosaurs, including the corporation’s signature Brontosaurus.

Ford Motor Company Pavilion

The Ford Motor Company introduced the Ford Mustang automobile to the public at its pavilion on April 17, 1964.

Films

The fair was also a showplace for independent films. One of the most noted was a religious film titled Parable, which showed at the Protestant Pavilion. It depicted humanity as a traveling circus and Christ as a clown. This marked the beginning of a new depiction of Jesus, and was the inspiration for the musical Godspell. Parable later went on to be honored at Cannes, as well as the Edinburgh Film Festival and Venice Film Festival. Another religious film was presented by the evangelist Billy Graham (who had sponsored his own pavilion) called Man in the 5th Dimension, which was shot in the 70mm Todd-AO widescreen process for exclusive presentation in a specially designed theater equipped with audio equipment that enabled viewers to listen to the film in Chinese, French, German, Japanese, Russian, and Spanish. The 13 and one-half minute film Man’s Search for Happiness was made for the Mormon Pavilion and was shown within the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints for decades.

The surprise hit of the fair was a non-commercial movie short presented by the SC Johnson Company (S.C. Johnson Wax) called To Be Alive!. The film celebrated the joy of life found worldwide and in all cultures, and it would later win a special award from the New York Film Critics Circle and an Academy Award for Best Documentary (Short Subject).

Disney Influence

Fountains and a reflecting pool mark the approach to the Unisphere

Fountains and a reflecting pool mark the approach to the Unisphere

The fair also is remembered as the venue Walt Disney used to design and perfect his system of “Audio-Animatronics“, in which a combination of electromechanical actuators and computers controls the movement of lifelike robots to act out scenes. Walt Disney Productions designed and created four shows at the fair:

- In “Pepsi Presents Walt Disney’s ‘It’s a Small World‘ – a Salute to UNICEF and the World’s Children” at the Pepsi pavilion, animated dolls and animals frolicked in a spirit of international unity accompanying a boat ride around the world. The song was written by the Sherman Brothers. Each of the animated dolls had an identical face, originally designed by New York (Valley Stream) artist Gregory S. Marinello in partnership with Walt Disney himself.

- General Electric sponsored “Progressland”, where an audience seated in a revolving auditorium (the “Carousel of Progress“) viewed an audio-animatronic presentation of the progress of electricity in the home. The Sherman Brotherssong “There’s a Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow” was composed for this attraction. The highlight of the exhibit demonstrated a brief plasma “explosion” of controlled nuclear fusion. The crowd-pleasing loud crack that was produced could be heard even on the line outside in the neighboring Travelers Insurance pavilion.

- Ford Motor Company presented “Ford’s Magic Skyway“, a WED Imagineering designed pavilion, which was the second most popular exhibit at the fair. It featured 50 actual (motorless) convertible Ford vehicles, including Ford Mustangs, in an early prototype of what would become the PeopleMover ride system. Audience members entered the vehicles on a main platform as they moved slowly along the track. The ride moved the audience through scenes featuring life-sized audio-animatronic dinosaurs and cavemen. Walt Disney Productions had earlier been asked by General Motors to produce their exhibit, which also featured a similar ride and dioramas, but Disney had declined this job.

- At the Illinois pavilion, a lifelike President Abraham Lincoln, voiced by Royal Dano, recited his famous speeches in “Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln.”

After the fair, there was some discussion of the Disney company retaining these exhibits on-site and converting Flushing Meadows Park into an East Coast version of Disneyland, but this idea was abandoned. Instead, Disney relocated several of these exhibits to Disneyland in Anaheim, California and subsequently replicated them at other Disney theme parks. Today’s Walt Disney World in Orlando, Florida is essentially the realization of the original concept of an “East Coast Disneyland” with Epcot Center designed as a “permanent” world’s fair.

After the fair, there was some discussion of the Disney company retaining these exhibits on-site and converting Flushing Meadows Park into an East Coast version of Disneyland, but this idea was abandoned. Instead, Disney relocated several of these exhibits to Disneyland in Anaheim, California and subsequently replicated them at other Disney theme parks. Today’s Walt Disney World in Orlando, Florida is essentially the realization of the original concept of an “East Coast Disneyland” with Epcot Center designed as a “permanent” world’s fair.

All four attractions from 1964 are still represented in one way or another: Two attractions from the fair are relatively unchanged, including a replica of “It’s a small world” and the original (albeit updated) Carousel of Progress. Versions of “It’s a small world” are an attraction at all five Disney Magic Kingdom-style parks, and its theme song is among the most widely known on the planet.

The two remaining attractions exist as evolutions of the originals. The dinosaurs from Ford’s Magic Skyway became the Disneyland Railroad Primeval World diorama, and the motorized tires embedded in the track which propelled and regulated the speed of ride vehicles inspired Disneyland’s PeopleMover, and later the Tomorrowland Transit Authority of Walt Disney World Resort‘s Magic Kingdom. “Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln” was expanded into The Hall of Presidents.

Meanwhile, Disneyland still hosts the original “It’s a small world” and “Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln” transferred from New York, as well as the now-unused track of the original Disneyland PeopleMover based on the Ford’s Magic Skyway. The original Carousel of Progress was first moved to Disneyland in 1967 and then to its current home at the (Florida) Magic Kingdom in 1973.

Disney later used technologies developed for the fair to create the Pirates of the Caribbean attraction. Epcot Center‘s original attractions borrowed heavily from the audio-animatronic advances of the fair and its general design guidelines.

Failure of Amusements

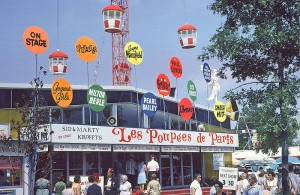

The Krofft’s “Les Poupées de Paris Pavilion”

The Krofft’s “Les Poupées de Paris Pavilion”

One of the fair’s major crowd-attracting and financial shortcomings was the absence of a midway. The fair’s organizers were opposed, on principle, to the honky-tonk atmosphere engendered by midways, and this was another thing that irked the BIE, which insisted that all officially sanctioned fairs have a midway. What amusements the fair actually had ended up being largely dull. The Meadow Lake Amusement Area was not easily accessible, and officials objected to shows being advertised.

Furthermore, although the Amusement Area was supposed to remain open for four hours after the exhibits closed at 10 pm, the fair presented a fountain-and-fireworks show every night at 9 pm at the Pool of Industry. Fairgoers would see this show and then leave the fair rather than head to the Amusement Area; one was hard pressed to see anyone on the fairgrounds by midnight.

The fair’s big entertainment spectacles, including the “Wonder World” at the Meadow Lake Amphitheater, “To Broadway with Love” in the Texas Pavilion, and Dick Button‘s “Ice-travaganza” in the New York City Pavilion, all closed ahead of schedule, with heavy losses. It became apparent that fairgoers did not go to the fair for its entertainment value, especially as there was plenty of entertainment in Manhattan.

A notable exception to this situation was Les Poupées de Paris (The Dolls of Paris), an adults-only musical puppet show created, produced and directed by Sid and Marty Krofft. This show, modeled after the Paris revues Lido and Folies Bergère, was heavily attended, and financially successful.

Controversial Ending

The fair ended in controversy over allegations of financial mismanagement. Controversy had plagued it during much of its two-year run. The Fair Corporation had taken in millions of dollars in advance ticket sales for both the 1964 and 1965 seasons. However, the receipts of these sales were booked entirely against the first season of the fair.[5] This made it appear that the fair had plenty of operating cash when, in fact, it was borrowing from the second season’s gate to pay the bills. Before and during the 1964 season, the fair spent much money despite attendance that was below expectations. By the end of the 1964 season, Moses and the press began to realize that there would not be enough money to pay the bills and the fair teetered on bankruptcy. In March 1965 a group of bankers and politicians asked showman Billy Rose to take over the fair, which he declined stating: “I’d rather be hit by a baseball bat” and “cancer in its last stages never attracted me very much.”

The fair ended in controversy over allegations of financial mismanagement. Controversy had plagued it during much of its two-year run. The Fair Corporation had taken in millions of dollars in advance ticket sales for both the 1964 and 1965 seasons. However, the receipts of these sales were booked entirely against the first season of the fair.[5] This made it appear that the fair had plenty of operating cash when, in fact, it was borrowing from the second season’s gate to pay the bills. Before and during the 1964 season, the fair spent much money despite attendance that was below expectations. By the end of the 1964 season, Moses and the press began to realize that there would not be enough money to pay the bills and the fair teetered on bankruptcy. In March 1965 a group of bankers and politicians asked showman Billy Rose to take over the fair, which he declined stating: “I’d rather be hit by a baseball bat” and “cancer in its last stages never attracted me very much.”

While the 1939–1940 New York World’s Fair returned 40 cents on the dollar to bond investors, the 1964/1965 fair returned only 19.2 cents on the dollar.

On-site Legacy

The Unisphere on July 31, 2010.

The Unisphere on July 31, 2010.

New York City was left with a much improved Flushing Meadows Park following the fair, taking possession of the park from the Fair Corporation in June 1967. Today, it is heavily used for both walking and recreation. The paths and their names remain almost unchanged from the days of the fair.

At the center of the park stands the symbol of “Man’s Achievements on a Shrinking Globe in an Expanding Universe” – the fair’s Unisphere symbol, depicting our earth of “The Space Age.” The Unisphere was made famous again in 1997 when it was featured in the film Men in Black. The Unisphere has become a symbol of Queens, and has appeared on the cover of the borough’s telephone directory books.

The city also inherited a multi-million dollar Science Museum and Space Park exhibiting the rockets and vehicles used in America’s early space exploration projects. The Space Park deteriorated due to neglect, but in 2004 the surviving rockets were restored and placed back on display. The outdoors exhibit is now part of the expanded New York Hall of Science, a portion of whose building is also a remnant of the fair.

The carousel that was the centerpiece of Carousel Park in the Lake Amusement Area (which was previously two carousels from Coney Island that were merged for the fair) was relocated to the former Transportation Area outside of the Queens Zoo in the park where it still operates today.

The ruins of the observatory towers in 2006

The ruins of the observatory towers in 2006

Both the New York State Pavilion and the United States Pavilion were retained for future use. No reuse was ever found for the U.S. Pavilion, however, and it became severely deteriorated and vandalized. The building was ultimately demolished in 1977.

The New York State Pavilion found no residual use other than as TV and movie sets, such as an episode of McCloud; for The Wiz; and part of the setting (and the plot) for Men in Black. In the decades after the fair closed, it remained an abandoned and badly neglected relic, with its roof gone and the once bright floors and walls almost faded away. Once the red ceiling tiles were removed from the pavilion in the late 1970s for safety reasons, the Texaco terrazzo floor map of New York State was subject to the elements of weather and was ruined. Some conservation and restoration efforts were demonstrated in 2008 by researchers from the University of Pennsylvania, and a handful of local groups advocated for funds to complete the floor’s restoration. The New York State Pavilion was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2009. In the fall of 2013, New York City’s Department of Parks and Recreation announced plans to restore the pavilion with new landscaped paths and event spaces at an estimated cost of $73 million, as opposed to the $14 million cost to demolish the structure.

In 1994, the Queens Theatre took over the Circarama adjacent to the towers and continues to operate there, using the ruined state pavilion as a storage depot. Nearby, the fair’s Heliport has been repurposed as an elevated banquet/catering facility called Terrace on the Park.

Of the two structures from the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair that survived though the 1964-65 Fair—the New York City Pavilion, and the Billy Rose Aquacade and Amphitheater—only the New York City building is still standing. The Amphitheater fell into disrepair in the 1980s and was torn down in 1996. The former New York City Pavilion is now home to the Queens Museum, which also continues to display the multi-million dollar scale model “Panorama of the City of New York,” updated from time to time. As of 2012, the historic 1939 structure also has an excellent display of memorabilia from the two world’s fairs. For many years, the section where the early United Nations General Assembly once met was reverted to its historic role as an ice skating rink, but in 2009 the skating rink was moved to a new recreation center across the park. In April 2011, the Queens Museum broke ground on an ambitious expansion project at the old skating rink that almost doubled its floor space, bringing the total to about 100,000 square feet (9,300 m2).

Of the two structures from the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair that survived though the 1964-65 Fair—the New York City Pavilion, and the Billy Rose Aquacade and Amphitheater—only the New York City building is still standing. The Amphitheater fell into disrepair in the 1980s and was torn down in 1996. The former New York City Pavilion is now home to the Queens Museum, which also continues to display the multi-million dollar scale model “Panorama of the City of New York,” updated from time to time. As of 2012, the historic 1939 structure also has an excellent display of memorabilia from the two world’s fairs. For many years, the section where the early United Nations General Assembly once met was reverted to its historic role as an ice skating rink, but in 2009 the skating rink was moved to a new recreation center across the park. In April 2011, the Queens Museum broke ground on an ambitious expansion project at the old skating rink that almost doubled its floor space, bringing the total to about 100,000 square feet (9,300 m2).

In 1978, Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, as it is now called, became the home of the United States Tennis Association, and the US Open tennis tournament is played there annually. The former Singer Bowl, later renamed Louis Armstrong Stadium, was the tournament’s primary venue, until the larger Arthur Ashe Stadium was built on the site of the former Federal Pavilion and opened in August 1997. Collectively, the complex is called the USTA National Tennis Center.

In 1978, Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, as it is now called, became the home of the United States Tennis Association, and the US Open tennis tournament is played there annually. The former Singer Bowl, later renamed Louis Armstrong Stadium, was the tournament’s primary venue, until the larger Arthur Ashe Stadium was built on the site of the former Federal Pavilion and opened in August 1997. Collectively, the complex is called the USTA National Tennis Center.