Juneteenth

“The Roots of Juneteenth” – Galveston, TX

Every year, visitors to Galveston Island “come on home where it all began” to celebrate one of the largest Juneteenth celebrations in the country! Did you know Juneteenth — a holiday now celebrated in more than 40 states — began in Galveston, Texas? Galveston holds the distinction of being the place the last slaves in the United States were freed. Find out more in this short video and don’t forget to visit www.galveston.com/juneteenth!

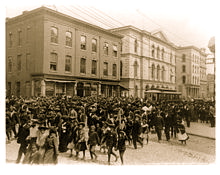

Juneteenth celebration in Austin, Texas, on June 19, 1900

Juneteenth celebration in Austin, Texas, on June 19, 1900

Juneteenth, also known as Juneteenth Independence Day or Freedom Day, is a holiday that commemorates the announcement of the abolition of slavery in Texas in June 1865, and more generally the emancipation of African-American slaves throughout the Confederate South. Celebrated on June 19, the term is a portmanteau of June and nineteenth and is recognized as a state holiday or special day of observance in most states.

The holiday is observed primarily in local celebrations. Traditions include public readings of the Emancipation Proclamation, singing traditional songs such as “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” and “Lift Every Voice and Sing”, and readings by noted African-American writers such as Ralph Ellison and Maya Angelou. Celebrations may include parades, rodeos, street fairs, cookouts, family reunions, park parties, historical reenactments, or Miss Juneteenth contests.

History

Ashton Villa, from whose front balcony General Order #3 was read on June 19, 1865

Ashton Villa, from whose front balcony General Order #3 was read on June 19, 1865

During the American Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862, with an effective date of January 1, 1863. It declared all slaves to be freed in the Confederate States of America in rebellion and not in Union hands (this excluded Maryland, Delaware, Tennessee, “West” and Southeast Virginia and lower Louisiana, which were occupied by the Union). It also announced that the Union would start recruiting former slaves and free blacks to serve in the military and recruitment began in the spring of 1863. Slaves often escaped to Union lines for protection and many began to serve in the military. In some areas, contraband camps were set up to house the freedmen temporarily, as well as start schools and put adults to work. Lincoln had urged the governments in the Border States, which had remained in the Union, to free their slaves under a system of gradual abolition but none did so. Those slaves were not emancipated until the end of the war.

Even when slaves gained freedom, this was a difficult era. Conditions in contraband camps were crowded, with poor sanitation, as existed in most military encampments. Just as more soldiers on both sides died of disease rather than wounds, because of the social disruption from the war and general harsh conditions, many former slaves died of disease in the years from 1862 to 1870, including from a smallpox epidemic.

More isolated geographically, Texas was not a battleground, and thus its slaves were not affected by the Emancipation Proclamation unless they escaped. Planters and other slaveholders had migrated into Texas from eastern states to escape the fighting, and many brought their slaves with them, increasing by the thousands the number of slaves in the state at the end of the Civil War.

By 1865, there were an estimated 250,000 slaves in Texas. As news of end of the war moved slowly, it did not reach Texas until May 1865, and the Army of the Trans-Mississippi did not surrender until June 2. On June 18, 1865, Union General Gordon Granger arrived at Galveston Island with 2,000 federal troops to occupy Texas on behalf of the federal government. On June 19, standing on the balcony of Galveston’s Ashton Villa, Granger read aloud the contents of “General Order No. 3,” announcing the total emancipation of slaves:

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

Emancipation Day celebration in Richmond, Virginia in 1905

Emancipation Day celebration in Richmond, Virginia in 1905

Former slaves in Galveston rejoiced in the streets after the announcement, although in the years afterward many struggled to work through the changes against resistance of whites. But, the following year, freedmen organized the first of what became annual celebrations of Juneteenth in Texas. Barred in some cities from using public parks because of state-sponsored segregation of facilities, across parts of Texas, freed people pooled their funds to purchase land to hold their celebrations, such as Houston’s Emancipation Park, Mexia’s Booker T. Washington Park, and Emancipation Park in Austin.

In the early 20th century, economic and political forces led to a decline in Juneteenth celebrations. From 1890 to 1908, Texas and all former Confederate states passed new constitutions or amendments that effectively disenfranchised blacks, excluding them from the political process. White-dominated state legislatures passed Jim Crow laws imposing second-class status. The Great Depression forced many blacks off farms and into the cities to find work. In these urban environments, African Americans had difficulty taking the day off to celebrate. From 1940 through 1970, in the second wave of the Great Migration, more than 5 million blacks left Texas, Louisiana and other parts of the South for the North and West Coast, where jobs were available in the defense industry for World War II. As historian Isabel Wilkerson writes, “The people from Texas took Juneteenth Day to Los Angeles, Oakland, Seattle, and other places they went.”

By the 1950’s and 1960’s, the Civil Rights movement focused the attention of African-American youth on the struggle for racial equality and the future. But, many linked these struggles to the historical struggles of their ancestors. Following the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign to Washington, D.C. called by Rev. Ralph Abernathy, many attendees returned home and initiated Juneteenth celebrations in areas where the day was not previously celebrated.

Since the 1980s and 1990s, the holiday has been more widely celebrated among African-American communities. In 1994 a group of community leaders gathered at Christian Unity Baptist Church in New Orleans, Louisiana to work for greater national celebration of Juneteenth.[10] Paul Herring Chairman of The Juneteenth Committee credits Mrs. E. Hill Deloney (Community Matriarch) for starting the celebration in Flint, Michigan in the late 1980s; as he said, “… It’s a time to Reflect & Rejoice, because we are the children of those who chose to survive.” Juneteenth informal observance have spread to many other states, including Portland, Maine, in part carried by Texans. Expatriates have celebrated it in cities abroad, such as Paris. Some US military bases in other countries sponsor celebrations, in addition to those of private groups.

Organizations such as the National Juneteenth Observance Foundation are working toward gaining Congressional approval to designate Juneteenth as a national day of observance. Others are working to have its 150th anniversary celebrated worldwide.