Hurricane Katrina

CNN Jack Cafferty – Hurricane Katrina Outrage

In late August, 2005, Jack Cafferty appeared on CNN to express his outrage at the lack of a coordinated federal response to the calamity known as Hurricane Katrina. “Where the hell is the water for these people?” he asked, while informing viewers that in his 62 years, he’d never seen anything so outrageous.

Refuge of Last Resort – The true Hurricane Katrina Story

This no holds documentary chronicles the days before, during and after Hurricane Katrina. Told from the viewpoint of several families stuck in New Orleans, this moving and unflinching story says so much by saying so little. Most of this footage has never been seen by the public, and there is absolutely no stock footage used in this film.

August 25, 2005 – Hurricane Katrina makes landfall near the Broward/Miami-Dade Countyborder, producing gusty winds and heavy rainfall peaking at 16.33 inches (415 mm) in Perrine. Damage amounts to $523 million (2005 USD, $577 million 2008 USD) in the southern portion of the state, and twelve people die in southern Florida; three from drowning, three from falling trees, and six from indirect causes. Minor damage is reported along the Florida Panhandlefrom its landfall in Mississippi. Katrina was only a Category 1 at the time, only to become a monstrous Category 5 days later and wreak havoc along the Gulf Coast.

August 25, 2005 – Hurricane Katrina makes landfall near the Broward/Miami-Dade Countyborder, producing gusty winds and heavy rainfall peaking at 16.33 inches (415 mm) in Perrine. Damage amounts to $523 million (2005 USD, $577 million 2008 USD) in the southern portion of the state, and twelve people die in southern Florida; three from drowning, three from falling trees, and six from indirect causes. Minor damage is reported along the Florida Panhandlefrom its landfall in Mississippi. Katrina was only a Category 1 at the time, only to become a monstrous Category 5 days later and wreak havoc along the Gulf Coast.

Hurricane Katrina was the deadliest and most destructive Atlantic hurricane of the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season. It is the costliest natural disaster, as well as one of the five deadliest hurricanes, in the history of the United States. Among recorded Atlantic hurricanes, it was the sixth strongest overall. At least 1,836 people died in the actual hurricane and in the subsequent floods, making it the deadliest U.S. hurricane since the 1928 Okeechobee hurricane; total property damage was estimated at $81 billion (2005 USD), nearly triple the damage wrought by Hurricane Andrew in 1992.

Hurricane Katrina formed over the Bahamas on August 23, 2005 and crossed southern Florida as a moderate Category 1 hurricane, causing some deaths and flooding there before strengthening rapidly in the Gulf of Mexico. The storm weakened before making its second landfall as a Category 3 storm on the morning of Monday, August 29 in southeast Louisiana. It caused severe destruction along the Gulf coast from central Florida to Texas, much of it due to the storm surge. The most significant number of deaths occurred in New Orleans, Louisiana, which flooded as the levee systemcatastrophically failed, in many cases hours after the storm had moved inland. Eventually 80% of the city and large tracts of neighboring parishes became flooded, and the floodwaters lingered for weeks. However, the worst property damage occurred in coastal areas, such as all Mississippi beachfront towns, which were flooded over 90% in hours, as boats and casino barges rammed buildings, pushing cars and houses inland, with waters reaching 6–12 miles (10–19 km) from the beach.

The hurricane surge protection failures in New Orleans are considered the worst civil engineering disaster in U.S history and prompted a lawsuit against the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), the designers and builders of the levee system as mandated by the Flood Control Act of 1965. Responsibility for the failures and flooding was laid squarely on the Army Corps in January 2008 by Judge Stanwood Duval, U.S. District Court, but the federal agency could not be held financially liable due to sovereign immunity in the Flood Control Act of 1928. There was also an investigation of the responses from federal, state and local governments, resulting in the resignation of Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) director Michael D. Brown, and of New Orleans Police Department (NOPD) Superintendent Eddie Compass.

Several agencies including the United States Coast Guard (USCG), National Hurricane Center (NHC), and National Weather Service (NWS) were commended for their actions. They provided accurate hurricane weather tracking forecasts with sufficient lead time. Unfortunately, even the most insistent appeals from national, state and local public officials to residents to evacuate before the storm did not warn that the levees could breach and fail.

Preparations – Main article: Preparations for Hurricane Katrina

Federal government

Flanked by Michael Chertoff, Secretary of Homeland Security, left, and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, President George W. Bush meets with members of the White House Task Force on Hurricane Katrina Recovery on August 31, 2005, in the Cabinet Room of the White House.

Flanked by Michael Chertoff, Secretary of Homeland Security, left, and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, President George W. Bush meets with members of the White House Task Force on Hurricane Katrina Recovery on August 31, 2005, in the Cabinet Room of the White House.

On the morning of Friday, August 26, at 10 am CDT (1500 UTC), Katrina had strengthened to a Category 3 storm in the Gulf of Mexico. Later that afternoon, the NHC realized that Katrina had yet to make the turn toward the Florida Panhandle and ended up revising the predicted track of the storm from the panhandle to the Mississippi coast. The NHC issued a hurricane watch for southeastern Louisiana, including the New Orleans area at 10 am CDT Saturday, August 27. That afternoon the NHC extended the watch to cover the Mississippi and Alabama coastlines as well as the Louisiana coast to Intracoastal City.

The United States Coast Guard began prepositioning resources in a ring around the expected impact zone and activated more than 400 reservists. On August 27, it moved its personnel out of the New Orleans region prior to the mandatory evacuation. Aircrews from the Aviation Training Center, in Mobile, staged rescue aircraft from Texas to Florida. All aircraft were returning towards the Gulf of Mexico by the afternoon of August 29. Air crews, many of whom lost their homes during the hurricane, began a round-the-clock rescue effort in New Orleans, and along the Mississippi and Alabama coastlines.

President of the United States George W. Bush declared a state of emergency in selected regions of Louisiana, Alabama, and Mississippi on Saturday, the 27th, two days before the hurricane made landfall. That same evening, the NHC upgraded the storm alert status from hurricane watch to hurricane warning over the stretch of coastline between Morgan City, Louisiana to the Alabama-Florida border, 12 hours after the watch alert had been issued, and also issued a tropical storm warning for the westernmost Florida Panhandle.

During video conferences involving the president on August 28 and 29, the director of the National Hurricane Center, Max Mayfield, expressed concern that Katrina might push its storm surge over the city’s levees and flood walls. In one conference, he stated, “I do not think anyone can tell you with confidence right now whether the levees will be topped or not, but that’s obviously a very, very great concern.”

On Sunday, August 28, as the sheer size of Katrina became clear, the NHC extended the tropical storm warning zone to cover most of the Louisiana coastline and a larger portion of the Florida Panhandle. The National Weather Service’s New Orleans/Baton Rouge office issued a vividly worded bulletin predicting that the area would be “uninhabitable for weeks” after “devastating damage” caused by Katrina, which at that time rivaled the intensity of Hurricane Camille. “On Sunday, August 28, President Bush spoke with Governor Blanco to encourage her to order a mandatory evacuation of New Orleans.” (Per page 235 of Special Report of the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs).

Voluntary and mandatory evacuations were issued for large areas of southeast Louisiana as well as coastal Mississippi and Alabama. About 1.2 million residents of the Gulf Coast were covered under a voluntary or mandatory evacuation order.

Investigation of State of Emergency declaration

In a September 26, 2005 hearing, former FEMA chief Michael Brown testified before a U.S. House subcommittee about FEMA’s response. During that hearing, Representative Stephen Buyer (R-IN) inquired as to why President Bush’s declaration of state of emergency of August 27 had not included the coastal parishes of Orleans, Jefferson, and Plaquemines. (In fact, the declaration did not include any of Louisiana’s coastal parishes, whereas the coastal counties were included in the declarations for Mississippi and Alabama). Brown testified that this was because Louisiana Governor Blanco had not included those parishes in her initial request for aid, a decision that he found “shocking.” After the hearing, Blanco released a copy of her letter, which showed she had requested assistance for “all the southeastern parishes including the City of New Orleans” as well specifically naming 14 parishes including Jefferson, Orleans and Plaquemines.

Gulf Coast

Radar image of Hurricane Katrina approaching landfall in Louisiana

Radar image of Hurricane Katrina approaching landfall in Louisiana

On August 26, the state of Mississippi activated its National Guard in preparation for the storm’s landfall. Additionally, the state government activated its Emergency Operations Center the next day, and local governments began issuing evacuation orders. By 6:00 pm CDT on August 28, 11 counties and eleven cities issued evacuation orders, a number which increased to 41 counties and 61 cities by the following morning. Moreover, 57 emergency shelters were established on coastal communities, with 31 additional shelters available to open if needed. Louisiana’s hurricane evacuation plan calls for local governments in areas along and near the coast to evacuate in three phases, starting with the immediate coast 50 hours before the start of tropical storm force winds. Persons in areas designated Phase II begin evacuating 40 hours before the onset of tropical storm winds and those in Phase III areas (including New Orleans) evacuate 30 hours before the start of such winds.

Many private caregiving facilities that relied on bus companies and ambulance services for evacuation were unable to evacuate their charges because they waited too long. Louisiana’s Emergency Operations Plan Supplement 1C(Part II, section II paragraph D) calls for use of school and other public buses in evacuations. Although buses that later flooded were available to transport those dependent upon public transportation, not enough bus drivers were available to drive them as Governor Blanco did not sign an emergency waiver to allow any licensed driver to transport evacuees on school buses. However, 20 year old Jabbar Gibson armed with only a standard operator’s permit took it upon himself to take a school bus and drive it to Houston with 50 to 70 evacuees. Some estimates claimed that 80% of the 1.3 million residents of the greater New Orleans metropolitan area evacuated, leaving behind substantially fewer people than remained in the city during the Hurricane Ivan evacuation.

By Sunday, August 28, most infrastructure along the Gulf Coast had been shut down, including all Canadian National Railway and Amtrak rail traffic into the evacuation areas as well as the Waterford Nuclear Generating Station. The NHC maintained the coastal warnings until late on August 29, by which time Hurricane Katrina was over central Mississippi.

City of New Orleans – See also: Hurricane preparedness for New Orleans

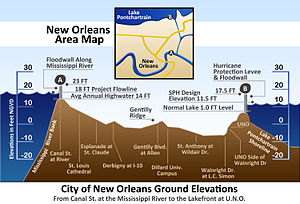

Vertical cross-section of New Orleans, showing maximum levee height of 23 feet (7 m). Vertical scale exaggerated.

Vertical cross-section of New Orleans, showing maximum levee height of 23 feet (7 m). Vertical scale exaggerated.

By August 26, the possibility of unprecedented cataclysm was already being considered. Many of the computer models had shifted the potential path of Katrina 150 miles (240 km) westward from the Florida Panhandle, putting the city of New Orleans directly in the center of their track probabilities; the chances of a direct hit were forecast at 17%, with strike probability rising to 29% by August 28. This scenario was considered a potential catastrophe because some parts of New Orleans and the metro area are below sea level. Since the storm surge produced by the hurricane’s right-front quadrant (containing the strongest winds) was forecast to be 28 feet (8.5 m), emergency management officials in New Orleans feared that the storm surge could go over the tops of levees protecting the city, causing major flooding.

At a news conference at 10 am on August 28, shortly after Katrina was upgraded to a Category 5 storm, New Orleans mayor Ray Nagin ordered the first-ever mandatory evacuation of the city, calling Katrina “a storm that most of us have long feared.” The city government also established several “refuges of last resort” for citizens who could not leave the city, including the massive Louisiana Superdome, which sheltered approximately 26,000 people and provided them with food and water for several days as the storm came ashore.

Florida

Many people living in the South Florida area were unaware when Katrina strengthened from a tropical storm to a hurricane in one day and struck southern Florida near the Miami-Dade – Broward county line. The hurricane struck between the cities of Aventura, in Miami-Dade County, and Hallandale, in Broward County, on Thursday, August 25, 2005. However, National Hurricane Center (NHC) forecasts had correctly predicted that Katrina would intensify to hurricane strength before landfall, and hurricane watches and warnings were issued 31.5 hours and 19.5 hours before landfall, respectively — only slightly less than the target thresholds of 36 and 24 hours.

Florida Governor Jeb Bush declared a state of emergency on August 24 in advance of Hurricane Katrina’s landfall in Florida. Shelters were opened and schools closed in several counties in the southern part of the state. A number of evacuation orders were also issued, mostly voluntary, although a mandatory evacuation was ordered for vulnerable housing in Martin County.

Impact – Main article: Hurricane Katrina effects by region

In Katrina’s Wake – Short Film NASA

In Katrina’s Wake – Short Film NASA

| Alabama | 2 |

| Florida | 14 |

| Georgia | 2 |

| Kentucky | 1 |

| Louisiana | 1,577* |

| Mississippi | 238 |

| Ohio | 2 |

| Total | 1,836 |

|---|---|

| Missing | 135 |

| *Includes out-of-state evacuees counted by Louisiana |

|

Flooding in the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans after Hurricane Betsy in 1965.

On August 29, Katrina’s storm surge caused 53 different levee breaches in greater New Orleans, submerging eighty percent of the city. A June 2007 report by the American Society of Civil Engineers indicated that two-thirds of the flooding were caused by the multiple failures of the city’s floodwalls. Not mentioned were the flood gates that were not closed. The storm surge also devastated the coasts of Mississippi and Alabama, making Katrina the most destructive and costliest natural disaster in the history of the United States, and the deadliest hurricane since the 1928 Okeechobee Hurricane. The total damage from Katrina is estimated at $81.2 billion (2005 U.S. dollars), nearly double the cost of the previously most expensive storm, Hurricane Andrew, when adjusted for inflation.

The confirmed death toll (total of direct and indirect deaths) is 1,836, mainly from Louisiana (1,577) and Mississippi (238). However, 135 people remain categorized as missing in Louisiana, and many of the deaths are indirect, but it is almost impossible to determine the exact cause of some of the fatalities.

Federal disaster declarations covered 90,000 square miles (233,000 km2) of the United States, an area almost as large as the United Kingdom. The hurricane left an estimated three million people without electricity. On September 3, 2005, Homeland SecuritySecretary Michael Chertoff described the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina as “probably the worst catastrophe, or set of catastrophes,” in the country’s history, referring to the hurricane itself plus the flooding of New Orleans.

Even in 2010, debris remained in some coastal communities.

South Florida and Cuba

Damage to a mobile home in Davie, Florida following Hurricane Katrina

Main article: Effects of Hurricane Katrina in Florida

Hurricane Katrina first made landfall on August 25, 2005 in South Florida where it hit as a Category 1 hurricane, with 80 mph (130 km/h) winds. Rainfall was heavy in places and exceeded 14 inches (350 mm) in Homestead, Florida, and a storm surge of 3 – 5 feet (1.5 m) was measured in parts of Monroe County. More than 1 million customers were left without electricity, and damage in Florida was estimated from $1 – $2 billion, with most of the damage coming from flooding and overturned trees. There were 14 fatalities reported in Florida as a result of Hurricane Katrina.

Most of the Florida Keys experienced tropical-storm force winds from Katrina as the storm’s center passed to the north, with hurricane force winds reported in the Dry Tortugas. Rainfall was also high in the islands, with 10 inches (250 mm) falling on Key West. On August 26, a strong F1 tornado formed from an outer rain band of Katrina and struck Marathon. The tornado damaged a hangar at the airport there and caused an estimated $5 million in damage.

Although Hurricane Katrina stayed well to the north of Cuba, on August 29 it brought tropical-storm force winds and rainfall of over 8 inches (200 mm) to western regions of the island. Telephone and power lines were damaged and around 8,000 people were evacuated in the Pinar del Río Province. According to Cuban television reports the coastal city of Surgidero de Batabano was 90% underwater.

Louisiana

Flooding in Venice, Louisiana

On August 29, Hurricane Katrina made landfall near Buras-Triumph, Louisiana with 125 mph (205 km/h) winds, as a strong Category 3 storm. However, as it had only just weakened from Category 4 strength and the radius of maximum winds was large, it is possible that sustained winds of Category 4 strength briefly impacted extreme southeastern Louisiana. Although the storm surge to the east of the path of the eye in Mississippi was higher, a very significant surge affected the Louisiana coast. The height of the surge is uncertain because of a lack of data, although a tide gauge in Plaquemines Parish indicated a storm tide in excess of 14 feet (4.3 m) and a 12-foot (3 m) storm surge was recorded in Grand Isle. Hurricane Katrina made final landfall near the mouth of the Pearl River, with the eye straddling St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana and Hancock County, Mississippi, on the morning of August 29 at about 9:45M CST.

Hurricane Katrina also brought heavy rain to Louisiana, with 8 – 10 inches (200 – 250 mm) falling on a wide swath of the eastern part of the state. In the area around Slidell, the rainfall was even higher, and the highest rainfall recorded in the state was approximately 15 inches (380 mm). As a result of the rainfall and storm surge the level of Lake Pontchartrain rose and caused significant flooding along its northeastern shore, affecting communities from Slidell to Mandeville. Several bridges were destroyed, including the I-10 Twin Span Bridge connecting Slidell to New Orleans. Almost 900,000 people in Louisiana lost power as a result of Hurricane Katrina.

Katrina’s storm surge inundated all parishes surrounding Lake Pontchartrain, including St. Tammany, Tangipahoa, St. John the Baptist and St. Charles Parishes. St. Tammany Parish received a two-part storm surge. The first surge came as Lake Pontchartrain rose and the storm blew water from the Gulf of Mexico into the lake. The second came as the eye of Katrina passed, westerly winds pushed water into a bottleneck at the Rigolets Pass, forcing it farther inland. The range of surge levels in eastern St. Tammany Parish is estimated at 13 to 16 feet (4.9 m), not including wave action.

Hard-hit St. Bernard Parish was flooded due to breaching of the levees that contained a navigation channel called the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet (MR-GO) and the breach of the Levee Board designed and built 40 Arpent canal levee. The search for the missing was undertaken by the St. Bernard Fire Department due to the assets of the United States Coast Guard being diverted to New Orleans. Many of the missing in the months after the storm were tracked down by searching flooded homes, tracking credit card records, and visiting homes of family and relatives.

Hurricane Katrina making landfall in New Orleans, Louisiana.

According to the U.S. Dept. of Housing and Urban Development, in St. Bernard Parish, 81% (20,229) of the housing units were damaged. In St. Tammany Parish, 70% (48,792) were damaged and in Placquemines Parish 80% (7,212) were damaged.

In addition, the combined effect of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita was the destruction of an estimated 562 square kilometres (217 sq mi) of coastal wetlands in Louisiana.

New Orleans

Main articles: Effects of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans and 2005 levee failures in Greater New Orleans

Flooded I-10/I-610/West End Blvd interchange and surrounding area of northwest New Orleans and Metairie, Louisiana

As the eye of Hurricane Katrina swept to the northeast, it subjected the city to hurricane conditions for hours. Although power failures prevented accurate measurement of wind speeds in New Orleans, there were a few measurements of hurricane-force winds. From this the NHC concluded that it is likely that much of the city experienced sustained winds of Category 1 or Category 2 strength.

Katrina’s storm surge led to 53 levee breaches in the federally built levee system protecting metro New Orleans and the failure of the 40 Arpent Canal levee. Nearly every levee in metro New Orleans was breached as Hurricane Katrina passed just east of the city limits. Failures occurred in New Orleans and surrounding communities, especially St. Bernard Parish. The Mississippi River Gulf Outlet (MR-GO) breached its levees in approximately 20 places, flooding much of east New Orleans, most of Saint Bernard Parish and the East Bank of Plaquemines Parish. The major levee breaches in the city included breaches at the 17th Street Canal levee, the London Avenue Canal, and the wide, navigable Industrial Canal, which left approximately 80% of the city flooded.

Most of the major roads traveling into and out of the city were damaged. The only routes out of the city were the westbound Crescent City Connection and the Huey P. Long Bridge, as large portions of the I-10 Twin Span Bridge traveling eastbound towards Slidell, Louisiana had collapsed. Both the Lake Pontchartrain Causeway and the Crescent City Connection only carried emergency traffic.

On August 29, at 7:40 am CDT, it was reported that most of the windows on the north side of the Hyatt Regency New Orleans had been blown out, and many other high rise buildings had extensive window damage. The Hyatt was the most severely damaged hotel in the city, with beds reported to be flying out of the windows. Insulation tubes were exposed as the hotel’s glass exterior was completely sheared off.

Southeast United States

Flood waters come up the steps of Mobile’s federal courthouse.

Although Hurricane Katrina made landfall well to the west, Alabama and the Florida Panhandle were both affected by tropical-storm force winds and a storm surge varying from 12 to 16 feet (3–5 m) around Mobile Bay, with higher waves on top. Sustained winds of 67 mph (107 km/h) were recorded in Mobile, Alabama, and the storm surge there was approximately 12 feet (3.7 m). The surge caused significant flooding several miles inland along Mobile Bay. Four tornadoes were also reported in Alabama. Ships, oil rigs, boats and fishing piers were washed ashore along Mobile Bay: the cargo ship M/VCaribbean Clipper and many fishing boats were grounded at Bayou La Batre.

An oil rig under construction along the Mobile River broke its moorings and floated 1.5 miles (2 km) northwards before striking the Cochrane Bridge just outside Mobile. No significant damage resulted to the bridge and it was soon reopened. The damage on Dauphin Island was severe, with the surge destroying many houses and cutting a new canal through the western portion of the island. An offshore oil rig also became grounded on the island. As in Mississippi, the storm surge caused significant beach erosion along the Alabama coastline. More than 600,000 people lost power in Alabama as a result of Hurricane Katrina and two people died in a traffic accident in the state. Residents in some areas, such as Selma, were without power for several days.

Bayou La Batre: cargo ship and fishing boats were grounded

Along the Florida Panhandle the storm surge was typically about five feet (1.5 m) and along the west-central Florida coast there was a minor surge of 1 – 2 feet (0.3 – 0.6 m). In Pensacola, Florida 56 mph (90 km/h) winds were recorded on August 29. The winds caused damage to some trees and structures and there was some minor flooding in the Panhandle. There were two indirect fatalities from Katrina in Walton County as a result of a traffic accident. In the Florida Panhandle, 77,000 customers lost power.

The flood of New Orleans from a boat on Canal Street (early September, 2005).

Northern and central Georgia were affected by heavy rains and strong winds from Hurricane Katrina as the storm moved inland, with more than 3 inches (75 mm) of rain falling in several areas. At least 18 tornadoes formed in Georgia on August 29, the most on record in that state for one day in August. The most serious of these tornadoes was an F2 tornado which affected Heard County and Carroll County. This tornado caused 3 injuries and one fatality and damaged several houses. In addition this tornado destroyed several poultry barns, killing over 140,000 chicks. The other tornadoes caused significant damages to buildings and agricultural facilities. In addition to the fatality caused by the F2 tornado, there was another fatality in a traffic accident.

Looting and violence

Further information: Effects of Hurricane Katrina on New Orleans

A Border Patrol Special Response Team searches a hotel room-by-room in New Orleans in response to Hurricane Katrina.

Shortly after the hurricane moved away on August 30, 2005, some residents of New Orleans who remained in the city began looting stores. Many were in search of food and water that were not available to them through any other means, as well as non-essential items.

Reports of carjacking, murders, thefts, and rapes in New Orleans flooded the news. Some sources later determined that many of the reports were inaccurate, because of the confusion. Thousands of National Guard and federal troops were mobilized (the total went from 7,841 in the area the day Katrina hit to a maximum of 46,838 on September 10) and sent to Louisiana along with numbers of local law enforcement agents from across the country who were temporarily deputized by the state. “They have M16s and are locked and loaded. These troops know how to shoot and kill and I expect they will,” Louisiana Governor Kathleen Blanco said. Congressman Bill Jefferson (D-LA) told ABC News: “There was shooting going on. There was sniping going on. Over the first week of September, law and order were gradually restored to the city.” Several shootings occurred between police and New Orleans residents, some involving police misconduct; including a fatal incident at Danziger Bridge.

A number of arrests were made throughout the affected area, including some near the New Orleans Convention Center. A temporary jail was constructed of chain link cages in the city train station.

In Texas, where more than 300,000 refugees were located, local officials ran 20,000 criminal background checks on the refugees, as well as on the relief workers helping them and people who opened up their homes. The background checks found that 45% of the refugees had a criminal record of some nature, and that 22% had a violent criminal record. The number of homicides in Houstonfrom September 2005 through February 22, 2006 went up by 23% relative to the same period a year before; 29 of the 170 murders involved displaced Louisianans as victims or suspects.

The United States Northern Command established Joint Task Force (JTF) Katrina based out of Camp Shelby, Mississippi, to act as the military’s on-scene response on Sunday, August 28, with US Army Lieutenant General Russel L. Honoré as commander. Approximately 58,000 National Guard personnel were activated to deal with the storm’s aftermath, with troops coming from all 50 states. The Department of Defense also activated volunteer members of the Civil Air Patrol.

Michael Chertoff, Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, decided to take over the federal, state, and local operations officially on August 30, 2005, citing the National Response Plan. This was refused by Governor Blanco who indicated that her National Guard could manage. Early in September, Congress authorized a total of $62.3 billion in aid for victims. Additionally, President Bush enlisted the help of former presidents Bill Clinton and George H.W. Bush to raise additional voluntary contributions, much as they did after the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami. American flags were also ordered to be half-staff from September 2, 2005 to September 20, 2005 in honor of the victims.

FEMA provided housing assistance (rental assistance, trailers, etc.) to more than 700,000 applicants—families and individuals. However, only one-fifth of the trailers requested in Orleans Parish were supplied, resulting in an enormous housing shortage in the city of New Orleans. Many local areas voted to not allow the trailers, and many areas had no utilities, a requirement prior to placing the trailers. To provide for additional housing, FEMA has also paid for the hotel costs of 12,000 individuals and families displaced by Katrina through February 7, 2006, when a final deadline was set for the end of hotel cost coverage. After this deadline, evacuees were still eligible to receive federal assistance, which could be used towards either apartment rent, additional hotel stays, or fixing their ruined homes, although FEMA no longer paid for hotels directly. As of March 30, 2010, there were still 260 families living in FEMA-provided trailers in Louisiana and Mississippi.

Law enforcement and public safety agencies, from across the United States, provided a “mutual aid” response to Louisiana and New Orleans in the weeks following the disaster. Many agencies responded with manpower and equipment from as far away as California, Michigan, Nevada, New York, and Texas. This response was welcomed by local Louisiana authorities as their staff were either becoming fatigued, stretched too thin, or even quitting from the job.

Two weeks after the storm, more than half of the states were involved in providing shelter for evacuees. By four weeks after the storm, evacuees had been registered in all 50 states and in 18,700 zip codes—half of the nation’s residential postal zones. Most evacuees had stayed within 250 miles (400 km), but 240,000 households went to Houston and other cities over 250 miles (400 km) away and another 60,000 households went over 750 miles (1,200 km) away.