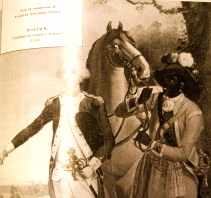

William “Billy” Lee

WILLIAM “BILLY” LEE

William “Billy” Lee was no ordinary slave on George Washington’s Mount Vernon plantation. As Washington’s favorite huntsman before the Revolutionary War and the general’s personal valet, body servant and close companion during the war, Lee served his master loyally and well.

William “Billy” Lee was no ordinary slave on George Washington’s Mount Vernon plantation. As Washington’s favorite huntsman before the Revolutionary War and the general’s personal valet, body servant and close companion during the war, Lee served his master loyally and well.

Lee also held his own beside the skilled middle-age commander with his own riding skill and endurance. He displayed an “uncommon degree of courage” each time he followed the general into battle. And in high-level social and professional gatherings he conducted himself with poise and intelligence.

In short, Lee was equal to any horseman or gentleman and was an invaluable military aide to whom Washington referred as “my servant” or “my fellow,” but never as “my slave.”

When Washington died in 1799, he specified in his will that Lee was to be free. It was the beginning of the long journey to emancipation for all Mount Vernon slaves.

Had he been a white man, Lee would have held a prominent place in history books because of his close relationship with the general and the many wartime adventures they shared.

But he wasn’t white. He was black, and for most of his life a slave, and as such was largely ignored by historians. Nevertheless, he occupied a position of uncommon influence during a pivotal time in American history.

Lee came to Mount Vernon as a teen. Washington bought him from the widow of Col. John Lee of Westmoreland County in 1768. In diary entries years later, Lee became a prominent figure in Washington’s life. Three times a week Lee joined the general hunting. Lee was a fearless horseman who “would rush, at full speed, through brake or tangled wood, in a style at which modern huntsman would stand aghast.”

During the war, Lee and Washington were inseparable. Whatever the commander in chief needed, even amid the volley of gunfire, Lee was at his side, ready to assist. Such loyalty and courage did not go unnoticed. Washington bid a favor from a friend to arrange passage for Lee’s wife from Philadelphia to Virginia.

But after leaving the battlefields unscathed, Lee became accident-prone. On a trip to Washington in 1785, he fell and broke his kneecap.

Three years later, he fell again while on an errand to the Alexandria Post Office and broke his other knee. Thus crippled, he lost his status as Washington’s No. 1 slave and became the plantation’s shoemaker.

When Washington died, his will bequeathed Lee his immediate freedom. The will also gave Lee the option of remaining on the estate, with food, clothing and an annual pension of $30 for life. This, Washington wrote, was given “as a testimony for his attachment to me and for his faithful services during the Revolutionary War.”

Lee stayed at the plantation. Records indicate he became an alcoholic and died about 1828, when he would have been about 78 years old.

The significance, and the timing, of Washington’s decision to free Billy Lee are debated to this day. Some observers argue that the president should have freed his brave slave – and for that matter all his slaves – long before Washington’s death.

But at least one historian characterized Washington’s posthumous freeing of Lee as an “acknowledgment that Billy Lee and the other Mount Vernon slaves who would follow him to freedom deserved a rightful place alongside white men in a future multiracial society.”

Edited By: Allen P. Duncan, 2001