United States Prison Systems

Prisons for Profit

Corporations are running many Americans prisons, but will they put profits before prisoners? A grim new statistic: One in every hundred Americans is now locked behind bars. As the prison population grows faster than the government can build prisons, private companies see an opportunity for profit. This week, NOW on PBS investigates the government’s trend to outsource prisons and prisoners to the private sector. Critics accuse private prisons of standing in the way of sentencing reform and sacrificing public safety to maximize profits. “The notion that a corporation making a profit off this practice is more important to us than public safety or the human rights of prisoners is outrageous,” Judy Greene, a criminal policy analyst, tells NOW on PBS. Companies like Corrections Corporation of America say they’re doing their part to solve the problem of inmate overflow and a shortage of beds without sacrificing safety. “You don’t cut corners to where it’s going to be a safety, security or health issue,” Richard Smelser, warden of the Crowley Correctional Facility in Colorado tells NOW. The prison is run by Corrections Corporation, which had revenues of over $1.4 billion last year. The Crowley prison made headlines back in 2004 after a major prison riot caused overwhelmed staff to run away from the facility. Outside law enforcement had to come in to put down the uprising. “The problems that were identified in the wake of the riot are typical of the private prison industry and happen over and over again,” Green tells NOW. More From NOW: Prisons for Profit | Immigrant Detainees: Profit Center? Reporter’s Notebook: Inside a Private Prison | In Your State: Prison Costs | Feedback Forum | Transcript. Related Reports Maximum Capacity Digging Out of Debt & Death Row Inmate Anthony Graves By the Numbers: America’s Prisons, Topic Search: Business, Law/Courts, Society and this week NOW travels to Colorado, where the controversy over private prisons is boiling over. The hot question: should incarceration be incorporated?

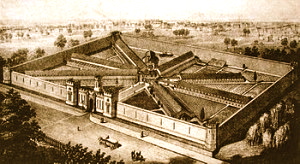

Eastern State Penitentiary, constructed in the 1820’s during the first major wave of penitentiary building in the United States

Eastern State Penitentiary, constructed in the 1820’s during the first major wave of penitentiary building in the United States

Imprisonment as a form of criminal punishment which only became widespread in the United States after the American Revolution, though penal incarceration efforts had been ongoing in England since as early as the 1500’s, and prisons in the form of dungeons and various detention facilities had existed since long before then. Prison building efforts in the United States came in three major waves. The first began during the Jacksonian Era and led to widespread use of imprisonment and rehabilitative labor as the primary penalty for most crimes in nearly all states by the time of the American Civil War. The second began after the Civil War and gained momentum during the Progressive Era, bringing a number of new mechanisms—such as parole, probation, and indeterminate sentencing—into the mainstream of American penal practice. Finally, since the early 1970s, the United States has engaged in a historically unprecedented expansion of its imprisonment systems at both the federal and state level. Since 1973, the number of incarcerated persons in the United States has increased five-fold, and in a given year 7 million persons are under the supervision or control of correctional services in the United States. These periods of prison construction and reform produced major changes in the structure of prison systems and their missions, the responsibilities of federal and state agencies for administering and supervising them, as well as the legal and political status of prisoners themselves.

Intellectual origins of United States Prisons

Incarceration as a form of criminal punishment is “a comparatively recent episode in Anglo-American jurisprudence,” according to historian Adam J. Hirsch. Before the nineteenth century, sentences of penal confinement were rare in the criminal courts of British North America. But penal incarceration had been utilized in England as early as the reign of the Tudors, if not before. When post-revolutionary prisons emerged in United States, they were, in Hirsch’s words, not a “fundamental departure” from the former American colonies’ intellectual past. Early American prisons systems like Massachusetts’ Castle Island Penitentiary, built in 1780, essentially imitated the model of the 1500’s English workhouse.

Incarceration as a form of criminal punishment is “a comparatively recent episode in Anglo-American jurisprudence,” according to historian Adam J. Hirsch. Before the nineteenth century, sentences of penal confinement were rare in the criminal courts of British North America. But penal incarceration had been utilized in England as early as the reign of the Tudors, if not before. When post-revolutionary prisons emerged in United States, they were, in Hirsch’s words, not a “fundamental departure” from the former American colonies’ intellectual past. Early American prisons systems like Massachusetts’ Castle Island Penitentiary, built in 1780, essentially imitated the model of the 1500’s English workhouse.

The English Workhouse

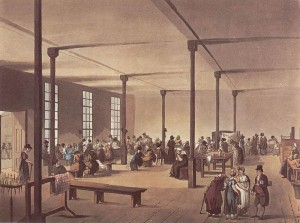

“The workroom at St James’s workhouse,” from The Microcosm of London (1808)

“The workroom at St James’s workhouse,” from The Microcosm of London (1808)

The English workhouse, an intellectual forerunner of early United States penitentiaries, was first developed as a “cure” for the idleness of the poor. Over time English officials and reformers came to see the workhouse as a more general system for rehabilitating criminals of all kinds.

Common wisdom in the England of the 1500s attributed property crime to idleness. “Idleness” had been a status crime since Parliament enacted the Statute of Laborers in the mid-fourteenth century. By 1530, English subjects convicted of leading a “Rogishe or Vagabonds Trade or Lyfe” were subject to whipping and mutilation, and recidivists could face the death penalty.

In 1557, many in England perceived that vagrancy was on the rise. That same year, the City of London reopened the Bridewell as a warehouse for vagrants arrested within the city limits. By order of any two of the Bridewell’s governors, a person could be committed to the prison for a term of custody ranging from several weeks to several years. In the decades that followed, “houses of correction” or “workhouses” like the Bridewell became a fixture of towns across England—a change made permanent when Parliament began requiring every county in the realm to build a workhouse in 1576.

The workhouse was not just a custodial institution. At least some of its proponents hoped that the experience of incarceration would rehabilitate workhouse residents through hard labor. Supporters expressed the belief that forced abstinence from “idleness” would make vagrants into productive citizens. Other supporters argued that the threat of the workhouse would deter vagrancy, and that inmate labor could provide a means of support for the workhouse itself. Governance of these institutions was controlled by written regulations promulgated by local authorities, and local justices of the peace monitored compliance.

Although “vagrants” were the first inhabitants of the workhouse—not felons or other criminals—expansion of its use to criminals was discussed. Sir Thomas More described in Utopia (1516) how an ideal government should punish citizens with slavery, not death, and expressly recommended use of penal enslavement in England. Thomas Starkey, chaplain to Henry VIII, suggested that convicted felons “be put in some commyn work . . . so by theyr life yet the commyn welth schold take some profit.” Edward Hext, justice of the peace in Somersetshire in the 1500s, recommended that criminals be put to labor in the workhouse after receiving the traditional punishments of the day.

Former workhouse in Nantwich, dating from 1780

Former workhouse in Nantwich, dating from 1780

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, several programs experimented with sentencing various petty criminals to the workhouse. Many petty criminals were sentenced to the workhouse by way of the vagrancy laws even before these efforts. A commission appointed by King James I in 1622 to reprieve felons condemned to death with banishment to the American colonies was also given authority to sentence offenders “to toyle in some such heavie and painful manuall workes and labors here at home and be kept in chains in the house of correction or other places,” until the King or his ministers decided otherwise. Within three years, a growing body of laws authorized incarceration in the workhouse for specifically enumerated petty crimes.

Throughout the 1700s, even as England’s “Bloody Code” took shape, incarceration at hard labor was held out as an acceptable punishment for criminals of various kinds—e.g., those who received a suspended death sentence via the benefit of clergy or a pardon, those who were not transported to the colonies, or those convicted of petty larceny. In 1779—at a time when the American Revolution had made convict transportation to North America impracticable—the English Parliament passed the Penitentiary Act, mandating the construction of two London prisons with internal regulations modeled on the Dutch workhouse—i.e., prisoners would labor more or less constantly during the day, with their diet, clothing, and communication strictly controlled. Although the Penitentiary Act promised to make penal incarceration the focal point of English criminal law, a series of the penitentiaries it prescribed were never constructed.

Despite the ultimate failure of the Penitentiary Act, however, the legislation marked the culmination of a series of legislative efforts that “disclose the . . . antiquity, continuity, and durability” of rehabilitative incarceration ideology in Anglo-American criminal law, according to historian Adam J. Hirsch. The first United States penitentiaries involved elements of the early English workhouses—hard labor by day and strict supervision of inmates.

English Philanthropist Penology

John Howard, English philanthropist penal reformer.

John Howard, English philanthropist penal reformer.

A second group that supported penal incarceration in England included clergymen and “lay pietists” of various religious denominations who made efforts during the 1700s to reduce the severity of the English criminal justice system. Initially, reformers like John Howard focused on the harsh conditions of pre-trial detention in English jails. But many philanthropists did not limit their efforts to jail administration and inmate hygiene; they were also interested in the spiritual health of inmates and curbing the common practice of mixing all prisoners together at random. Their ideas about inmate classification and solitary confinement match another undercurrent of penal innovation in the United States that persisted into the Progressive Era.

Beginning with Samuel Denne’s Letter to Lord Ladbroke (1771) and Jonas Hanway’s Solitude in Imprisonment (1776), philanthropic literature on English penal reform began to concentrate on the post-conviction rehabilitation of criminals in the prison setting. Although they did not speak with a single voice, the philanthropist penologists tended to view crime as an outbreak of the criminal’s estrangement from God. Hanway, for example, believed that the challenge of rehabilitating the criminal law lay in restoring his faith in, and fear of the Christian God, in order to “qualify [him] for happiness in both worlds.”

Philanthropist penal reformer Jonas Hanway, author of Solitude in Imprisonment (1776), circa 1785.

Philanthropist penal reformer Jonas Hanway, author of Solitude in Imprisonment (1776), circa 1785.

Many eighteenth-century English philanthropists proposed solitary confinement as a way to rehabilitate inmates morally. Since at least 1740, philanthropic thinkers touted the use of penal solitude for two primary purposes: (1) to isolate prison inmates from the moral contagion of other prisoners, and (2) to jump-start their spiritual recovery. The philanthropists found solitude far superior to hard labor, which only reached the convict’s worldly self, failing to get at the underlying spiritual causes of crime. In their conception of prison as a “penitentiary,” or place of repentance for sin, the English philanthropists departed from Continental models and gave birth to a largely novel idea—according to social historians Michael Meranze and Michael Ignatieff—which in turn found its way into penal practice in the United States.

A major political obstacle to implementing the philanthropists’ solitary program in England was financial: Building individual cells for each prisoner cost more than the congregate housing arrangements typical of eighteenth-century English jails. But by the 1790s, local solitary confinement facilities for convicted criminals appeared in Gloucestershire and several other English counties.

The philanthropists’ focus on isolation and moral contamination became the foundation for early penitentiaries in the United States. Philadelphians of the period eagerly followed the reports of philanthropist reformer John Howard And the archetypical penitentiaries that emerged in the 1820s United States—e.g., Auburn and Eastern State penitentiaries—both implemented a solitary regime aimed at morally rehabilitating prisoners. The concept of inmate classification—or dividing prisoners according to their behavior, age, etc.—remains in use in United States prisons to this day.

Rationalist Penology

Cesare Beccaria, Italian rationalist penal reformer and author of On Crimes and Punishments (1764).

Cesare Beccaria, Italian rationalist penal reformer and author of On Crimes and Punishments (1764).

A third group involved in English penal reform were the “rationalists” or “utlitarians.” According to historian Adam J. Hirsch, eighteenth-century rationalist criminology “rejected scripture in favor of human logic and reason as the only valid guide to constructing social institutions.

Eighteenth-century rational philosophers like Cesare Beccaria and Jeremy Bentham developed a “novel theory of crime”—specifically, that what made an action subject to criminal punishment was the harm it caused to other members of society. For the rationalists, sins that did not result in social harm were outside the purview of civil courts. With John Locke’s “sensational psychology” as a guide, which maintained that environment alone defined human behavior, many rationalists sought the roots of a criminal’s behavior in his or her past environment.

Rationalists differed as to what environmental factors gave rise to criminality. Some rationalists, including Cesare Beccaria, blamed criminality on the uncertainty criminal punishment, whereas earlier criminologists had linked criminal deterrence to the severity of punishment. In essence, Beccaria believed that where arrest, conviction, and sentencing for crime were “rapid and infallible,” punishments for crime could remain moderate. Beccaria did not take issue with the substance of contemporary penal codes—e.g., whipping and the pillory; rather, he took issue with their form and implementation.

Jeremy Bentham, English rationalist penal reformer and designer of the Panopticon.

Jeremy Bentham, English rationalist penal reformer and designer of the Panopticon.

Other rationalists, like Jeremy Bentham, believed that deterrence alone could not end criminality and looked instead to the social environment as the ultimate source of crime. Bentham’s conception of criminality led him to concur with philanthropist reformers on the need for rehabilitation of offenders. But, unlike the philanthropists, Bentham and like-minded rationalists believed the true goal of rehabilitation was to show convicts the logical “inexpedience” of crime, not their estrangement from religion. For these rationalists, society was the source of and the solution to crime.

Ultimately, hard labor became the preferred rationalist therapy. Bentham eventually adopted this approach, and his well-known design for the Panopticon prison called for inmates to labor in solitary cells for the course of their imprisonment. Another rationalist, William Eden, collaborated with John Howard and Justice William Blackstone in drafting the Penitentiary Act of 1779, which called for a penal regime of hard labor.

According to social and legal historian Adam J. Hirsch, the rationalists had only a secondary impact on United States penal practices. But their ideas—whether consciously adopted by United States prison reformers or not—resonate in various United States penal initiatives to the present day.

Historical development of United States prison systems

Although convicts played a significant role in British settlement of North America, according to legal historian Adam J. Hirsch “[t]he wholesale incarceration of criminals is in truth a comparatively recent episode in the history of Anglo-American jurisprudence.” Imprisonment facilities were present from the earliest English settlement of North America, but the fundamental purpose of these facilities changed in the early years of United States legal history as a result of a geographically widespread “penitentiary” movement. The form and function of prison systems in the United States has continued to change as a result of political and scientific developments, as well as notable reform movements during the Jacksonian Era, Reconstruction Era, Progressive Era, and the 1970s. But the status of penal incarceration as the primary mechanism for criminal punishment has remained the same since its first emergence in the wake of the American Revolution.

Early settlement, convict transportation, and the prisoner trade – Penal transportation

Richard Hakluyt, promoter of large-scale English settlement in the Jamestown Colony by convicts, as depicted in stained glass in the west window of the south transept of Bristol Cathedral.

Richard Hakluyt, promoter of large-scale English settlement in the Jamestown Colony by convicts, as depicted in stained glass in the west window of the south transept of Bristol Cathedral.

Prisoners and prisons appeared in North America simultaneous to the arrival of European settlers. Among the ninety or so men who sailed with the explorer known as Christopher Columbus were a young black man abducted from the Canary Islands and at least four convicts. By 1570, Spanish soldiers in St. Augustine, Florida, had built the first substantial prison in North America. As other European nations began to compete with Spain for land and wealth in the New World, they too turned to convicts to fill out the crews on their ships.

According to social historian Marie Gottschalk, convicts were “indispensable” to English settlement efforts in what is now the United States. In the late sixteenth century, Richard Hakluyt called for the large-scale conscription of criminals to settle the New World for England. But official action on Haklyut’s proposal lagged until 1606, when the English crown escalated its colonization efforts.

Sir John Popham’s colonial venture in present-day Maine was stocked, a contemporary critic complained, “out of all the gaols [jails] of England.” The Virginia Company, the corporate entity responsible for settling Jamestown, authorized its colonists to seize Native American children wherever they could “for conversion … to the knowledge and worship of the true God and their redeemer, Christ Jesus.” The colonists themselves lived, in effect, as prisoners of the Company’s governor and his agents. Men caught trying to escape were tortured to death; seamstresses who erred in their sewing were subject to whipping. One Richard Barnes, accused of uttering “base and detracting words” against the governor, was ordered to be “disarmed and have his arms broken and his tongue bored through with an awl” before being banished from the settlement entirely.

When control of the Virginia Company passed to Sir Edwin Sandys in 1618, efforts to bring large numbers of settlers to the New World against their will gained traction alongside less coercive measures like indentured servitude. Vagrancy statutes began to provide for penal transportation to the American colonies as an alternative to capital punishment in this period, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. At the same time, the legal definition of “vagrancy” was greatly expanded.

Under Queen Elizabeth I, English vagrancy laws began increasingly to provide for penal transportation as a substitute for capital sentences.

Under Queen Elizabeth I, English vagrancy laws began increasingly to provide for penal transportation as a substitute for capital sentences.

Soon, a royal commissions endorsed the notion that any felon—except those convicted of murder, witchcraft, burglary, or rape—could legally by transported to Virginia or the West Indies to work as a plantation servant. Sandys also proposed sending maids to Jamestown as “breeders,” whose costs of passage could be paid for by the planters who took them on as “wives.” Before long, over sixty such women had made the passage to Virginia, and more followed. King James I’s royal administration also sent “vagrant” children to the New World as servants. A letter in the Virginia Company’s records suggests that as many as 1,500 children were sent to Virginia between 1619 and 1617. By 1619, African prisoners were brought to Jamestown and sold as slaves as well, marking England’s entry into the Atlantic slave trade.

The infusion of kidnapped children, maids, convicts, and Africans to Virginia during the early part of the seventeenth century inaugurated a pattern that would continue for nearly two centuries. By 1650, the majority of British emigrants to colonial North America went as “prisoners” of one sort or another—whether as indentured servants, convict laborers, or slaves.

The prisoner trade became the “moving force” of English colonial policy after the Restoration—i.e., from the summer of 1660 onward—according to By 1680, the Reverend Morgan Godwyn estimated that almost 10,000 persons were spirited away to the Americas annually by the English crown.

Parliament accelerated the prisoner trade in the eighteenth century. Under England’s Bloody Code, a large portion of the realm’s convicted criminal population faced the death penalty. But pardons were common. During the eighteenth century, the majority of those sentenced to die in English courts were pardoned—often in exchange for voluntary transport to the colonies. In 1717, Parliament empowered the English courts to directly sentence offenders to transportation, and by 1769 transportation was the leading punishment for serious crime in Great Britain. Over two-thirds of those sentenced during sessions of the Old Bailey in 1769 were transported. The list of “serious crimes” warranting transportation continued to expand throughout the eighteenth century, as it had during the seventeenth. Historian A. Roger Ekirch estimates that as many as one-quarter of all British emigrants to colonial America during the 1700s were convicts. In the 1720’s, James Oglethorpe settled the colony of Georgia almost entirely with convict settlers.

The typical transported convict during the 1700’s was brought to the North American colonies on board a “prison ship.” Upon arrival, the convict’s keepers would bathe and clothe him or her (and, in extreme cases, provide a fresh wig) in preparation for a convict auction. Newspapers advertised the arrival of a convict cargo in advance, and buyers would come at an appointed hour to purchase convicts off the auction block.

The Old Newgate Prison inLondon was one of many detention centers that facilitated the convict trade between England and its American colonies during the 17th and 18th centuries.

Prisons played an essential role in the convict trade. Some ancient prisons, like the Fleet and Newgate, still remained in use during the high period of the American prisoner trade in the eighteenth century. But more typically an old house, medieval dungeonspace, or private structure would act as a holding pen for those bound for Americanplantations or the Royal Navy (under impressment). Operating clandestine prisons in major port cities for detainees whose transportation to the New World was not strictly legal, became a lucrative trade on both sides of the Atlantic in this period. Unlike contemporary prisons, those associated with the convict trade served a custodial, not a punitive function.

Many colonists in British North America resented convict transportation. As early as 1683, Pennsylvania’s colonial legislature attempted to bar felons from being introduced within its borders. Benjamin Franklin called convict transportation “an insult and contempt, the cruellest, that ever one people offered to another.” Franklin suggested that the colonies send some of North America’s rattlesnakes to England, to be set loose in its finest parks, in revenge. But transportation of convicts to England’s North American colonies continued until the American Revolution, and many officials in England saw it as a humane necessity in light of the harshness of the penal code and contemporary conditions in English jails. Dr. Samuel Johnson, upon hearing that British authorities might bow to continuing agitation in the American colonies against transportation, reportedly told James Boswell: “Why they are a race of convicts, and ought to be thankful for anything we allow them short of hanging!”

When the American Revolution ended the prisoner trade to North America, the abrupt halt threw Britain’s penal system into disarray, as prisons and jails quickly filled with the many convicts who previously would have moved on to the colonies. Conditions steadily worsened. It was during this crisis period in the English criminal justice system that penal reformer John Howard began his work. Howard’s comprehensive study of British penal practice, The State of the Prisons in England and Wales, was first published in 1777—one year after the start of the Revolution.

Colonial criminal punishments, jails, and workhouses

The “Old Gaol [Jail]” in Barnstable, Massachusetts, built in 1690 and operated until 1820, is today the oldest wooden jail in the United States of America.

The jail was built in 1690 by order of Plimouth and Massachusetts Bay Colony Courts. Used as a jail from 1690–1820; at one time moved and attached to the Constable’s home. The ‘Old Gaol’ was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1971.

Although jails were an early fixture of colonial North American communities, they generally did not serve as places of incarceration as a form of criminal punishment. Instead, the main role of the colonial American jail was as a non-punitive detention facility for pre-trial and pre-sentence criminal defendants, as well as imprisoned debtors. The most common penal sanctions of the day were fines, whipping, and community-oriented punishments like the stocks.

Jails were among the earliest public structures built in colonial British North America. The 1629 colonial charter of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, for example, granted the shareholders behind the venture the right to establish laws for their settlement “not contrarie to the lawes of our realm in England” and to administer “lawfull correction” to violators, and Massachusetts established a house of correction for punishing criminals by 1635. Colonial Pennsylvania built two houses of correction starting in 1682, and Connecticut established one in 1727. By the eighteenth century, every county in the North American colonies had a jail.

A whipping post or pillory, with stocks atop it, at the New Castle County Jail, Delaware, in 1897.

Colonial American jails were not the “ordinary mechanism of correction” for criminal offenders, according to social historian David Rothman. Criminal incarceration as a penal sanction was “plainly a second choice,” either a supplement to or a substitute for traditional criminal punishments of the day, in the words of historian Adam J. Hirsch. Eighteenth-century criminal codes provided for a far wider range of criminal punishments than contemporary state and federal criminal laws in the United States. Fines, whippings, the stocks, the pillory, the public cage, banishment, capital punishment at the gallows, penal servitude in private homes—all of these punishments came before imprisonment in British colonial America.

The most common sentence of the colonial era was a fine or a whipping, but the stocks were another common punishment—so much so that most colonies, like Virginia in 1662, hastened to build these before either the courthouse or the jail. The theocraticcommunities of Puritan Massachusetts imposed faith-based punishments like the admonition—a formal censure, apology, and pronouncement of criminal sentence (generally reduced or suspended), performed in front of the church-going community. Sentences to the colonial American workhouse—when they were actually imposed on defendants—rarely exceeded three months, and sometimes spanned just a single day.

Colonial jails served a variety of public functions other than penal imprisonment. Civil imprisonment for debt was one of these, but colonial jails also served as warehouses for prisoners-of-war and political prisoners (especially during the American Revolution). They were also an integral part of the transportation and slavery systems—not only as warehouses for convicts and slaves being put up for auction, but also as a means of disciplining both kinds of servants.

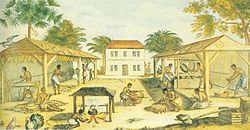

Depiction of slaves—another labor force brought to England’s American colonies in captivity—processing tobacco in 17th-century Virginia.

The colonial jail’s primary criminal law function was as a pre-trial and pre-sentence detention facility. Generally, only the poorest or most despised defendants found their way into the jails of colonial North America, since colonial judges rarely denied requests for bail. The only penal function of significance that colonial jails served was for contempt—but this was a coercive technique designed to protect the power of the courts, not a penal sanction in its own right.

The colonial jail differed from today’s United States prisons not only in its purpose, but in its structure. Many were no more than a cage or closet. Colonial jailers ran their institutions on a “familial” model and resided in an apartment attached to the jail, sometimes with a family of their own. The colonial jail’s design resembled an ordinary domestic residence, and inmates essentially rented their bed and paid the jailer for necessities.

Before the close of the American Revolution, few statutes or regulations defined the colonial jailers’ duty of care or other responsibilities. Upkeep was often haphazard, and escapes quite common. Few official efforts were made to maintain inmates’ health or see to their other basic needs.