The Shadow

The Shadow Returns (1946)

People are literally flying off balconies to their deaths as Lamont Cranston, aka the Shadow, tries to make sense out of a confusing jumble of murders. Director: Phil Rosen,

Writers: George Callahan (screenplay), George Callahan (story), Stars: Kane Richmond, Barbara Read and Tom Dugan.

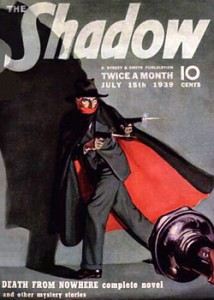

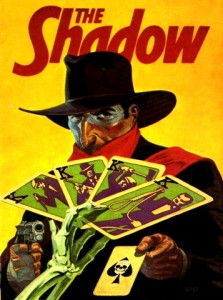

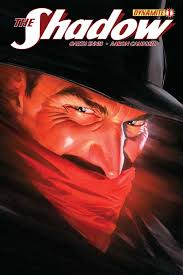

“Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men?” The Shadow as depicted on the cover of the July 15, 1939 issue of The Shadow Magazine. The story, “Death from Nowhere,” was one of the magazine plots adapted for the legendary radio drama.

“Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men?” The Shadow as depicted on the cover of the July 15, 1939 issue of The Shadow Magazine. The story, “Death from Nowhere,” was one of the magazine plots adapted for the legendary radio drama.

The Shadow is a collection of serialized dramas, originally in 1930’s pulp novels, and then in a wide variety of media. Details of the title character have varied across various media, but he is generally depicted as a crime-fighting vigilante with psychicpowers posing as a “wealthy, young man about town.” One of the most famous adventure heroes of the twentieth century, The Shadow has been featured on the radio, in a long running pulp magazine series, in comic books, comic strips, television, serials, video games, and at least five motion pictures. The radio drama is well-remembered for those episodes voiced by Orson Welles.

Introduced as a mysterious radio narrator by David Chrisman, William Sweets, and Harry Engman Charlot for Street and Smith Publications, The Shadow was developed fully and transformed into a pop culture icon by pulp writer Walter B. Gibson. The character would go on to become a major influence on the subsequent evolution of comic book superheroes, in particular, Batman.

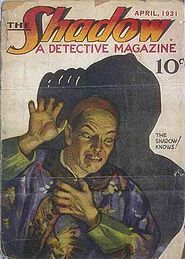

The Shadow debuted on July 31, 1930, as the mysterious narrator of the Street and Smith radio program Detective Story Hour. After gaining popularity among the show’s listeners, the narrator became the star of The Shadow Magazine on April 1, 1931, apulp series created and primarily written by the prolific Gibson.

The Shadow debuted on July 31, 1930, as the mysterious narrator of the Street and Smith radio program Detective Story Hour. After gaining popularity among the show’s listeners, the narrator became the star of The Shadow Magazine on April 1, 1931, apulp series created and primarily written by the prolific Gibson.

On September 26, 1937, The Shadow radio drama premiered with the story “The Deathhouse Rescue”, in which the character was characterized as having “the power to cloud men’s minds so they cannot see him.” This was a contrivance for the radio; in the magazine stories, The Shadow was not given the literal ability to become invisible.

The introduction from The Shadow radio program “Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows!” spoken by actor Frank Readick Jr., has earned a place in the American idiom. These words were accompanied by an ominous laugh and a musical theme, Camille Saint-Saëns‘ Le Rouet d’Omphale (“Omphale’s Spinning Wheel”, composed in 1872). At the end of each episode The Shadow reminded listeners that, “The weed of crime bears bitter fruit. Crime does not pay… The Shadow knows!”

Publication history – Detective Story Hour

In order to boost the sales of their Detective Story Magazine, Street and Smith Publications hired David Chrisman of the Ruthrauff & Ryan advertising agency and writer-director William Sweets to adapt the magazine’s stories into a radio series. Chrisman and Sweets felt the upcoming series should be narrated by a mysterious storyteller with a sinister voice, and began searching for a suitable name. One of their scriptwriters, Harry Engman Charlot, suggested various possibilities, such as “The Inspector” or “The Sleuth.” Charlot then proposed the ideal name for the phantom announcer: “… The Shadow.”

Thus, beginning on July 31, 1930, “The Shadow” was the name given to the mysterious narrator of the Detective Story Hour. The narrator was voiced by James LaCurto and, later, Frank Readick. The episodes were drawn from the Detective Story Magazine issued by Street and Smith, “the nation’s oldest and largest publisher of pulp magazines.” Although the latter company had hoped the radio broadcasts would boost the declining sales of the Detective Story Magazine, the result was quite different. Listeners found the sinister announcer much more compelling than the unrelated stories. They soon began asking newsdealers for copies of “that Shadow detective magazine,” even though it did not exist.

Development

Recognizing the demand and responding promptly, circulation manager Henry William Ralston of Street & Smith commissioned Walter B. Gibson to begin writing stories about “The Shadow.” Using the pen name of Maxwell Grant and claiming the stories were “from The Shadow’s private annals as told to” him, Gibson wrote 282 out of 325 tales over the next 20 years: a novel-length story twice a month (1st and 15th). The first story produced was “The Living Shadow“, published April 1, 1931.

Recognizing the demand and responding promptly, circulation manager Henry William Ralston of Street & Smith commissioned Walter B. Gibson to begin writing stories about “The Shadow.” Using the pen name of Maxwell Grant and claiming the stories were “from The Shadow’s private annals as told to” him, Gibson wrote 282 out of 325 tales over the next 20 years: a novel-length story twice a month (1st and 15th). The first story produced was “The Living Shadow“, published April 1, 1931.

Gibson initially fashioned the character as a man with villainous characteristics, who used them to battle crime, and in this was archetypal of the superhero, complete with a stylized imagery, a stylized name, sidekicks, supervillains, and a secret identity. Clad in black, The Shadow operated mainly after dark, burglarizing in the name of justice, and terrifying criminals into vulnerability before he or someone else gunned them down. The character was a film noir antihero in every sense; Gibson himself claimed the literary inspirations were Bram Stoker‘s Dracula and Edward Bulwer-Lytton‘s “The House and the Brain.”

Because of the great effort involved in writing two full-length novels every month, several guest writers were hired to write occasional installments in order to lighten Gibson’s work load. These guest writers included Lester Dent — who penned the Doc Savage stories — and Theodore Tinsley. In the late 1940’s, mystery novelist Bruce Elliott (also a magician) would temporarily replace Gibson as the primary author of the pulp series. Richard Edward Wormser, a reader for Street & Smith, wrote two Shadow stories.

The Shadow Magazine ceased publication with the Summer 1949 issue, but Walter B. Gibson wrote three new “official” stories between 1963 and 1980. The first of these began a new series of nine updated Shadow novels from Belmont Books, starting with Return of The Shadow under his own by-line. But the remaining eight, The Shadow Strikes, Beware Shadow, Cry Shadow, The Shadow’s Revenge, Mark of The Shadow, Shadow Go Mad, Night of The Shadow, and The Shadow, Destination: Moon, were not penned by Gibson but by Dennis Lynds under the “Maxwell Grant” byline. In these last eight novels, The Shadow was given psychic powers, including the radio character’s ability “to cloud men’s minds” so that he effectively became invisible, and was more of a spymaster than crime fighter.

Publications – List of The Shadow stories

Character development

The character and look of The Shadow gradually evolved over his lengthy fictional existence:

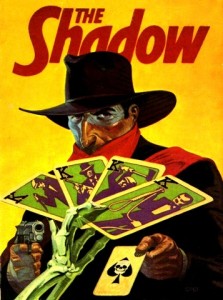

As depicted in the pulps, The Shadow wore a wide brimmed black hat and a black, crimson-lined cloak with an upturned collar over a standard black business suit. In the 1940s comic books, the later comic book series, and the 1994 film starring Alec Baldwin, he wore either the black hat or a wide-brimmed, black fedora and a crimson scarf just below his nose and across his mouth and chin. Both the cloak and scarf covered either a black doubled-breasted trench coat or regular black suit. As seen in some of the later comics series, the hat and scarf would also be worn with either a black Inverness coat or Inverness cape.

In the radio drama, which debuted in 1930, The Shadow was an invisible avenger who had learned, while “traveling through East Asia,” “the mysterious power to cloud men’s minds, so they could not see him.” This feature of the character was born out of necessity: time constraints of 1930’s radio made it difficult to explain to listeners where The Shadow was hiding and how he was remaining concealed. Thus, the character was given the power to escape human sight. Voice effects were added to suggest The Shadow’s seeming omnipresence. In order to explain this power, The Shadow was described as a master of hypnotism, as explicitly stated in several radio episodes.

Background

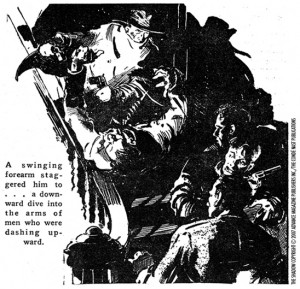

“The Living Shadow” from The Shadow #1 (April 7, 1931)

“The Living Shadow” from The Shadow #1 (April 7, 1931)

In print, The Shadow’s real name is Kent Allard, and he was a famed aviator who fought for the French during World War I. He became known by the alias of The Black Eagle, according to The Shadow’s Shadow, 1933, although later stories revised this alias as The Dark Eagle beginning withThe Shadow Unmasks, 1937. After the war, Allard seeks a new challenge and decides to wage war on criminals. Allard fakes his death in the South American jungles, then returns to the United States. Arriving in New York City, he adopts numerous identities to conceal his existence.

One of these identities—indeed, the best known—is Lamont Cranston, a “wealthy young man about town.” In the pulps, Cranston is a separate character; Allard frequently disguises himself as Cranston and adopts his identity (“The Shadow Laughs,” 1931). While Cranston travels the world, Allard assumes his identity in New York. In their first meeting, Allard/The Shadow threatens Cranston, saying that he has arranged to switch signatures on various documents and other means that will allow him to take over the Lamont Cranston identity entirely unless Cranston agrees to allow Allard to impersonate him when he is abroad. Terrified, Cranston agrees. The two men sometimes meet in order to impersonate each other (“Crime over Miami,” 1940). Apparently, the disguise works well because Allard and Cranston bear something of a resemblance to each other (“Dictator of Crime,” 1941).

His other disguises include businessman Henry Arnaud, who first appeared in Green Eyes, Oct. 1932, elderly gentleman Isaac Twambley, who first appeared in No Time For Murder, and Fritz, who first appeared in The Living Shadow,Apr. 1931; in this last disguise, he pretends to be a doddering old janitor who works at Police Headquarters in order to listen in on conversations.

The Shadow appears as Henry Arnaud in “Atoms of Death,” “Buried Evidence,” “Death Jewels,” “Death Premium,” “Death Ship,” “Green Eyes,” “House of Silence,” “Murder Trail,” “Quetzal,” “Realm of Doom,” “The Black Master,” “The Blue Sphinx,” “The Case of Congressman Coyd,” “The Circle of Death,” “The City of Doom,” “The Condor,” “The Embassy Murders,” “The Five Chameleons,” “The Ghost Murders,” “The Man From Shanghai,” “The Plot Master,” “The Radium Murders,” “The Romanoff Jewels,” “The Seven Drops of Blood,” “The Shadow Unmasks,” “The Shadow’s Shadow,” and “Wizard of Crime.”

The Shadow appears as Henry Arnaud in “Atoms of Death,” “Buried Evidence,” “Death Jewels,” “Death Premium,” “Death Ship,” “Green Eyes,” “House of Silence,” “Murder Trail,” “Quetzal,” “Realm of Doom,” “The Black Master,” “The Blue Sphinx,” “The Case of Congressman Coyd,” “The Circle of Death,” “The City of Doom,” “The Condor,” “The Embassy Murders,” “The Five Chameleons,” “The Ghost Murders,” “The Man From Shanghai,” “The Plot Master,” “The Radium Murders,” “The Romanoff Jewels,” “The Seven Drops of Blood,” “The Shadow Unmasks,” “The Shadow’s Shadow,” and “Wizard of Crime.”

The Shadow appears as Isaac Twambley in “No Time for Murder,” “Guardians of Death,” “Death Has Grey Eyes,” “The Stars Promise Death,” “Dead Man’s Chest, and “The Magigal’s Mystery.”

The Shadow appears as Fritz in at least 23 Shadow novels: “The Living Shadow,” “Hidden Death,” “The Ghost Makers,” “The Crime Clinic,” “Crime Circus,” “The Chinese Disks,” “The Dark Death,” “The Third Skull,” “The Black Master,” “The Voodoo Master,” “The Third Shadow,” “The Circle of Death,” “The Sledge Hammer Crimes,” “The Golden Masks,” “The Ghost Murders,” “Hills of Death,” “The Hand,” “The Racket’s King,” “The Green Hoods,” “The Crime Ray,” “The Getaway Ring,” “Masters of Death,” and “The Crystal Skull.”

For the first half of The Shadow’s tenure in the pulps, his past and identity are ambiguous, supposedly an intentional decision on Gibson’s part. In The Living Shadow, a thug claims to have seen The Shadow’s face, and thought he saw “a piece of white that looked like a bandage.” In “The Black Master” and “The Shadow’s Shadow”, the villains both see The Shadow’s true face, and they both remark that The Shadow is a man of many faces with no face of his own. It was not until the August 1937 issue, “The Shadow Unmasks,” that The Shadow’s real name is revealed.

Kent Allard appears as himself in at least twenty-eight Shadow novels: “The Shadow Unmasks,” “The Yellow Band,” “Death Turrets,” “The Sealed Box,” “The Crystal Buddha,” “Hills of Death,” “The Murder Master,” “The Golden Pagoda,” “Face of Doom,” “The Racket’s King,” “Murder for Sale,” “Death Jewels,” “The Green Hoods,” “Crime Over Boston,” “The Dead Who Lived,” “Shadow Over Alcatraz,” “Double Death,” “Silver Skull,” “The Prince of Evil,” “Masters of Death,” “Xitli, God of Fire,” “The Green Terror,” “The Wasp Returns,” “The White Column,” “Dictator of Crime,” “Crime out of Mind,” “Crime Over Casco,” and “Dead Man’s Chest.”

In the radio drama, the Allard secret identity was dropped for simplicity’s sake. On the radio, The Shadow was only Lamont Cranston; he had no other aliases or disguises.

Supporting characters

The Shadow has a network of agents who assist him in his war on crime. These include:

Margo Lane (Penelope Ann Miller) in The Shadow.

Margo Lane (Penelope Ann Miller) in The Shadow.

- Harry Vincent, an operative whose life he saved when Vincent tried to commit suicide.

- Moses “Moe” Shrevnitz, aka “Shrevvy,” a cab driver who doubles as his chauffeur. (Peter Boyle acted out the role in the 1994 film).

- Margo Lane, a socialite created for the radio drama and later introduced into the pulps. (Penelope Ann Miller acted out the role in the 1994 film, in which Margo was granted the power of telepathy, and hence the ability to pierce The Shadow’s hypnotic mental-clouding abilities).

- Clyde Burke, a newspaper reporter.

- Burbank, a radio operator who maintains contact between The Shadow and his agents.

- Clifford “Cliff” Marsland, a wrongly convicted ex-con who infiltrates gangs using his crooked reputation.

- Dr. Rupert Sayre, The Shadow’s personal physician.

- Jericho Druke, a giant, immensely strong black man.

- Slade Farrow, who works with The Shadow to rehabilitate criminals.

- Miles Crofton, who sometimes pilots The Shadow’s autogyro.

- Rutledge Mann, a stock-broker who collects information.

- Claude Fellows, the only agent of The Shadow ever to be killed, which he was in Gangdom’s Doom, 1931.

- Hawkeye, a reformed underworld snoop who trails gangsters and other criminals.

- Myra Reldon, a female operative who uses the alias of Ming Dwan when in Chinatown.

- Dr. Roy Tam, The Shadow’s contact man in New York’s Chinatown. (Sab Shimono acted him out in the 1994 film, where he provided valuable information to The Shadow when the latter was using his “normal” identity of Lamont Cranston.)

Though initially wanted by the police, The Shadow also works with and through them, notably gleaning information from his many chats with Commissioners Ralph Weston and Wainright Barth (who is also Cranston’s uncle; Jonathan Winters acted out the role in the 1994 film) while at the Cobalt Club. Weston believes that Cranston is merely a rich playboy who dabbles in detective work. Another police contact is Detective Joe Cardona, a key character in many Shadow novels.

In contrast to the pulps The Shadow radio drama limited the cast of major characters to The Shadow, Commissioner Weston, and Margo Lane, the last of whom was created specifically for the radio series, as it was believed the abundance of agents would make it difficult to distinguish between characters. Harry Vincent appeared as an agent of the Shadow in the first episode, “The Death House Escape.” Clyde Burke and Moe Shrevnitz (identified only as “Shrevvy”) made occasional appearances, but not as agents of The Shadow. Lt. Cardona was a minor character in passing in several episodes. Shrevvy was merely an acquaintance of Cranston and Lane, and occasionally Cranston’s chauffeur.

Enemies

The Shadow also faces a wide variety of enemies, ranging from kingpins and mad scientists to international spies and “super-villains,” many of whom were predecessors to the rogues galleries of comic super-heroes. Among The Shadow’s recurring foes are Shiwan Khan (The Golden Master, Shiwan Khan Returns, The Invincible Shiwan Khan, and Masters of Death),–who appears in the feature film portrayed by John Lone—The Voodoo Master (The Voodoo Master, The City of Doom, and Voodoo Trail), The Prince of Evil (The Prince of Evil, The Murder Genius, The Man Who Died Twice, and The Devil’s Paymaster, all written by Theodore Tinsley), and The Wasp (The Wasp and The Wasp Returns).

The series also featured a myriad of one-shot villains, including The Red Envoy, The Death Giver, Gray Fist, The Black Dragon, Silver Skull, The Red Blot, The Black Falcon, The Cobra, Zemba, The Black Master, Five-Face, The Gray Ghost, and Dr. Z.

The Shadow also battles collectives of criminals, such as The Silent Seven, The Hand, The Salamanders, and The Hydra.

Radio program

Orson Welles was the voice of The Shadow from September 1937 to October 1938. He was succeeded by Bill Johnstone.

Orson Welles was the voice of The Shadow from September 1937 to October 1938. He was succeeded by Bill Johnstone.

In early 1930, Street & Smith Publications hired David Chrisman and Bill Sweets to adapt the Detective Story Magazine to radio format. Chrisman and Sweets felt the program should be introduced by a mysterious storyteller. A young scriptwriter, Harry Charlot, suggested the name of “The Shadow.” Thus, “The Shadow” premiered over CBS airwaves on July 31, 1930, as the host of the Detective Story Hour, narrating “tales of mystery and suspense from the pages of the premier detective fiction magazine.” The narrator was first voiced by James LaCurto, but became a national sensation when radio veteran Frank Readick, Jr. assumed the role and gave it “a hauntingly sibilant quality that thrilled radio listeners.”

Early years

Following a brief tenure as narrator of Street & Smith’s Detective Story Hour, “The Shadow” character was used to host segments of The Blue Coal Radio Revue, playing on Sundays at 5:30 p.m. Eastern Standard Time. This marked the beginning of a long association between the radio persona and sponsor Blue Coal.

Following a brief tenure as narrator of Street & Smith’s Detective Story Hour, “The Shadow” character was used to host segments of The Blue Coal Radio Revue, playing on Sundays at 5:30 p.m. Eastern Standard Time. This marked the beginning of a long association between the radio persona and sponsor Blue Coal.

While functioning as a narrator of The Blue Coal Radio Revue, the character was recycled by Street & Smith in October 1931, to oddly serve as the storyteller of Love Story Hour.

In October 1932, the radio persona temporarily moved to NBC. Frank Readick again played the role of the sinister-voiced host on Mondays and Wednesdays, both at 6:30 p.m., with LaCurto taking occasional turns as the title character.

Readick returned as The Shadow to host a final CBS mystery anthology that fall. The series disappeared from CBS airwaves on March 27, 1935, due to Street & Smith’s insistence that the radio storyteller be completely replaced by the master crime-fighter described in Walter B. Gibson’s ongoing pulps.

Radio drama

Street & Smith entered into a new broadcasting agreement with Blue Coal in 1937, and that summer Gibson teamed with scriptwriter Edward Hale Bierstadt to develop the new series. As such, The Shadow returned to network airwaves on September 26, 1937, over the new Mutual Broadcasting System. Thus began the “official” radio drama that many Shadow fans know and love, with 22-year-old Orson Welles starring as Lamont Cranston, a “wealthy young man about town.” Once The Shadow joined Mutual as a half-hour series on Sunday evenings, the program did not leave the air until December 26, 1954.

Welles did not speak the signature line, “Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men?” Instead, Readick did, using a water glass next to his mouth for the echo effect. The famous catch phrase was accompanied by the strains of an excerpt from Opus 31 of the Camille Saint-Saëns classical composition, Le Rouet d’Omphale.

After Welles departed the show in 1938, Bill Johnstone was chosen to replace him and voiced the character for five seasons. Following Johnstone’s departure, The Shadow was portrayed by such actors as Bret Morrison (the longest tenure, with 10 years in two separate runs), John Archer, and Steve Courtleigh.

The Shadow also inspired another radio hit, The Whistler, with a similarly mysterious narrator.

The radio drama also introduced female characters into The Shadow’s realm, most notably Margo Lane (played by Agnes Moorehead, among others) as Cranston’s love interest, crime-solving partner and the only person who knows his identity as The Shadow. Four years later, the character was introduced into the pulp novels. Her sudden, unexplained appearance in the pulps annoyed readers and generated a flurry of hate mail printed in The Shadow Magazine’s letters page.

The radio drama also introduced female characters into The Shadow’s realm, most notably Margo Lane (played by Agnes Moorehead, among others) as Cranston’s love interest, crime-solving partner and the only person who knows his identity as The Shadow. Four years later, the character was introduced into the pulp novels. Her sudden, unexplained appearance in the pulps annoyed readers and generated a flurry of hate mail printed in The Shadow Magazine’s letters page.

Lane was described as Cranston’s “friend and companion” in later episodes, although the exact nature of their relationship was unclear. In the early scripts of the radio drama the character’s name was spelled “Margot.” The name itself was originally inspired by Margot Stevenson, the Broadway ingénue who would later be chosen to voice Lane opposite Welles’ Shadow during “the 1938 Goodrich summer season of the radio drama.” In the 1994 film in which Penelope Ann Miller portrayed the character, she is characterized as a telepath.

Comic strips, comic books, and graphic novels Walter Gibson‘s and Vernon Greene‘s The Shadow (August 12, 1940).

Walter Gibson‘s and Vernon Greene‘s The Shadow (August 12, 1940).

The Shadow has been adapted for the comics quite a few times during his long history; his first comics appearance was on June 17, 1940 as a syndicated daily newspaper comic strip offered through the Ledger Syndicate. The strip’s story continuity was written by Walter B. Gibson, with plot lines adapted from the Shadow pulps, and the strip was illustrated by Vernon Greene. Due to pulp paper shortages during World War II and the growing amount of space required for war news from both the European and Pacific fronts, the strip was canceled on June 13, 1942, after two years and nine adventures had been published. The Shadow daily was collected decades later in two comic book series from two different publishers (see below), first in 1988 and then in 1999.

To both cross-promote The Shadow and attract a younger audience to their other pulp magazines, Street & Smith published 101 issues of the comic book Shadow Comics from Vol. 1, #1 – Vol. 9, #5 (March 1940 – Sept. 1949). A Shadow story led off each issue, with the remainder of the stories being strips based on other Street & Smith pulp heroes.

In Mad #4 (April-May 1953), The Shadow was spoofed by Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder. Their character was called the Shadow’ (with an apostrophe), which is short for Lamont Shadowskeedeeboomboom. In this satire, Margo Pain gets Shad, as she calls him, into various predicaments, including fights with gangsters and a piano falling on him from above. At the conclusion of the tale, after Margo is tricked into going inside an outhouse surrounded by wired-up dynamite, Shad is seen gleefully pushing down a detonator’s plunger.

During the superhero revival of the 1960’s, Archie Comics published an eight-issue series, The Shadow (Aug. 1964 – Sept. 1965), under the company’s Mighty Comics imprint. In the first issue, The Shadow depicted was loosely based on the radio version, but with blond hair. In issue #2 (Sept. 1964), the character was transformed into a campy, heavily muscled, green and blue costume-wearing superhero by writer Robert Bernstein (Jerry Siegel) and artist John Rosenberger.

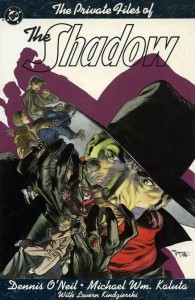

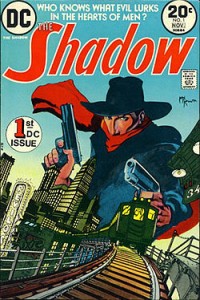

During the mid-1970s, DC Comics published an “atmospheric interpretation” of the character by writer Dennis O’Neil and artist Michael Kaluta in a 12-issue series (Nov. 1973 – Sept. 1975). Kaluta drew issues 1-4 and 6 and was followed by Frank Robbins and then E. R. Cruz. Faithful to both the pulp-magazine and radio-drama character, the series guest-starred fellow pulp fiction hero The Avenger in issue #11. The Shadow also appeared in DC’s Batman #253 (Nov. 1973), in which Batman teams with an aging Shadow and calls the famous crime fighter his “greatest inspiration”. In Batman #259 (Dec. 1974), Batman again meets The Shadow, and we learn The Shadow saved Bruce Wayne’s life when the future Batman was a boy.

DC Comics‘ The Shadow #1 (Nov. 1973). Cover art by Michael Kaluta.

DC Comics‘ The Shadow #1 (Nov. 1973). Cover art by Michael Kaluta.

The Shadow is also referenced in DC’s Detective Comics #446 (1975), page 4, panel 2: Batman, out of costume and in disguise as an older night janitor, makes a crime fighting acknowledgement, in a thought balloon, to the Shadow.

In 1986, another DC incarnation was created by Howard Chaykin. This four issue mini-series, also collected as a one-shot graphic novel (Shadow: Blood and Judgement), brought The Shadow into modern-day New York. While initially successful, this version proved unpopular with traditional Shadow fans because it depicted The Shadow using Uzi submachine guns and rocket launchers, as well as featuring a strong strain of black comedy and extreme violence throughout.

The Shadow, set in our modern era, was continued the following year, in 1987, as a monthly DC comics series by writer Andy Helfer (editor of the mini-series); it was drawn primarily by artists Bill Sienkiewicz (issues 1-6) and Kyle Baker (issues 8-19 and two Shadow Annuals).

In 1988 O’Neil and Kaluta, with inker Russ Heath, returned to The Shadow with the Marvel Comics graphic novel The Shadow 1941: Hitler’s Astrologer, set during World War II. This one-shot appeared in both hardcover and trade paperback editions.

The Vernon Greene/Walter Gibson Shadow newspaper comic strip from the early 1940’s was finally collected by Malibu Graphics (Malibu Comics) under their Eternity Comicsimprint, beginning with the first issue of Crime Classics dated July, 1988. Each cover was illustrated by Greene and colored by one of Eternity’s colorists. A total of 13 issues appeared featuring just the black-and-white daily until the final issue, dated November, 1989. Some of the Shadow story lines were contained in one issue, while others were continued over into the next. When a Shadow story ended, another tale would begin in the same issue. This back-to-back format continued until the final 13th issue, when the strip story lines ended.

The Vernon Greene/Walter Gibson Shadow newspaper comic strip from the early 1940’s was finally collected by Malibu Graphics (Malibu Comics) under their Eternity Comicsimprint, beginning with the first issue of Crime Classics dated July, 1988. Each cover was illustrated by Greene and colored by one of Eternity’s colorists. A total of 13 issues appeared featuring just the black-and-white daily until the final issue, dated November, 1989. Some of the Shadow story lines were contained in one issue, while others were continued over into the next. When a Shadow story ended, another tale would begin in the same issue. This back-to-back format continued until the final 13th issue, when the strip story lines ended.

Dave Stevens‘ nostalgic comics series The Rocketeer contains a great number of pop culture references to the 1930’s. Various characters from the Shadow pulps make appearances in the story line published in the Rocketeer Adventure Magazine, including The Shadow’s famous alter ego Lamont Cranston. Two issues were published by Comico Comics in 1988 and 1989, but the third and final installment did not appear until years later, finally appearing in 1995 from Dark Horse Comics. All three issues were then collected by Dark Horse into a slick trade paperback titled The Rocketeer: Cliff’s New York Adventure (ISBN 1-56971-092-9).

A year later, in 1989, DC re-released in hardcover and trade paper the first five issues of their 1970s series as a graphic novel, The Private Files of The Shadow. The volume also featured a new Shadow adventure drawn by Kaluta.

From 1989 to 1992, DC published a new Shadow series, The Shadow Strikes, written by Gerard Jones and Eduardo Barreto. This series was set in the 1930’s and returned The Shadow to his pulp origins. During its run, it featured The Shadow’s first team-up with Doc Savage, another very popular hero of the pulp magazine era. Both characters appeared together in a four-issue story line that crossed back and forth between each character’s DC comic series. “The Shadow Strikes” often led The Shadow into encounters with well-known celebrities of the 1930’s, such as Albert Einstein, Amelia Earhart, Charles Lindbergh, union organizer John L. Lewis, and Chicago gangsters Frank Nitti and Jake Guzik. In issue #7, The Shadow meets a radio announcer named Grover Mills, a character based on the young Orson Welles, who has been impersonating The Shadow on the radio. The character’s name is taken from Grover’s Mill, New Jersey, the name of the small town where the Martians land in Welles’ famous 1938 radio broadcast of The War of the Worlds. When Shadow rights holder Conde Nast increased its licensing fee, DC concluded the series after 31 issues and one annual; it became the longest running Shadow comic series since Street and Smith’s original 1940’s series.

During the early-to-mid-1990’s, Dark Horse Comics acquired the comics rights to the Shadow from Conde Nast. It published the Shadow miniseries In The Coils of Leviathan (four issues) in 1993, and Hell’s Heat Wave (three issues) in 1995. In the Coils of the Leviathan was later collected and issued by Dark Horse in 1994 as a trade paperback graphic novel. Both series were written by Joel Goss and Michael Kaluta, and drawn by Gary Gianni. A one-shot Shadow issue The Shadow and the Mysterious Three was also published by Dark Horse in 1994, again written by Joel Goss and Michael Kaluta, with Stan Manoukian and Vince Roucher taking over the illustration duties but working over Kaluta’s layouts. A comics adaptation of the 1994 film The Shadow was published in two issues by Dark Horse as part of the movie’s merchandising campaign. The script was by Goss and Kaluta and once again drawn from cover to cover by Kaluta. It was collected and published in England by Boxtree as a graphic novel tie-in for the film’s British release. Emulating DC’s earlier team-up, Dark Horse also published a two-issue mini-series in 1995 called The Shadow and Doc Savage. It was written by Steve Vance, and illustrated once again by Manoukian and Roucher. Of special note, both issues’ covers were drawn by Rocketeer creator Dave Stevens. The final Dark Horse Shadow team-up was published in 1995. It was a single issue of Ghost and the Shadow, written by Doug Moench, pencilled by H. M. Baker, and inked by Bernard Kolle.

During the early-to-mid-1990’s, Dark Horse Comics acquired the comics rights to the Shadow from Conde Nast. It published the Shadow miniseries In The Coils of Leviathan (four issues) in 1993, and Hell’s Heat Wave (three issues) in 1995. In the Coils of the Leviathan was later collected and issued by Dark Horse in 1994 as a trade paperback graphic novel. Both series were written by Joel Goss and Michael Kaluta, and drawn by Gary Gianni. A one-shot Shadow issue The Shadow and the Mysterious Three was also published by Dark Horse in 1994, again written by Joel Goss and Michael Kaluta, with Stan Manoukian and Vince Roucher taking over the illustration duties but working over Kaluta’s layouts. A comics adaptation of the 1994 film The Shadow was published in two issues by Dark Horse as part of the movie’s merchandising campaign. The script was by Goss and Kaluta and once again drawn from cover to cover by Kaluta. It was collected and published in England by Boxtree as a graphic novel tie-in for the film’s British release. Emulating DC’s earlier team-up, Dark Horse also published a two-issue mini-series in 1995 called The Shadow and Doc Savage. It was written by Steve Vance, and illustrated once again by Manoukian and Roucher. Of special note, both issues’ covers were drawn by Rocketeer creator Dave Stevens. The final Dark Horse Shadow team-up was published in 1995. It was a single issue of Ghost and the Shadow, written by Doug Moench, pencilled by H. M. Baker, and inked by Bernard Kolle.

The Shadow made an uncredited cameo appearance in issue #2 of DC’s 1996 four issue mini-series Kingdom Come. Those four issues were then collected into a single graphic novel in 1997. The Shadow appears in the nightclub scene standing in the background next to The Question and Rorschach.

The early 1940’s Shadow newspaper daily strip was again put back into print, this time by Avalon Communications under their ACG Classix imprint. The Shadow daily began appearing in the first issue of Pulp Action comics. It carries no monthly date or issue number on the cover, only a 1999 copyright and a “Pulp Action #1” notation at the bottom of the inside cover. Each issue’s cover is a colorized, partial comics panel blow-up, taken from one of the reprinted strips. The eighth issue uses for its cover a partial Shadow serial black-and-white movie still, with several hand-drawn alterations added. The first issue of Pulp Action is devoted entirely to reprinting the Shadow daily, but subsequent issues began offering back-up, non-Shadow stories of various page lengths in every issue. These Shadow strip reprints stopped with Pulp Action‘s eighth issue, never completing the daily’s story lines; that last issue carries a 2000 copyright date.

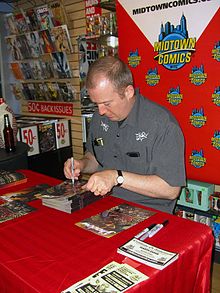

Writer Garth Ennis signing copies ofDynamite Entertainment‘s The Shadow(volume 5) #1 at an April 19, 2012 signing at Midtown Comics Downtown in Manhattan.

Writer Garth Ennis signing copies ofDynamite Entertainment‘s The Shadow(volume 5) #1 at an April 19, 2012 signing at Midtown Comics Downtown in Manhattan.

In August 2011, Dynamite licensed The Shadow from Conde Nast and would be developing new comic-book series around the character. The first series was written by Garth Ennisand illustrated by Aaron Campbell and debuted on April 19, 2012 in comics shops; it was also available for sale through various website sales outlets like eBay and Amazon.com. The Ennis story line was set during The Shadow’s original 1930s time frame. The first issue was published with four different retail color covers, plus eight additional special cover variants: These included four Retailer Incentive issues in 1:10, 1:25, 1:50, and 1:75 quantities and various regional comic shop limited print run specials; two were offered with hand-drawn original cover art sketches (one in pencil, the other in ink), that were signed, and numbered by their artists. This first issue of The Shadow was drawn by artists Alex Ross, Jae Lee, Howard Chaykin, and John Cassaday. The series continues with the same artists and four different retail covers offered for each issue, plus additional Retailer Incentive variant covers available at varying, higher prices, based on their more limited print runs. Each completed storyline is then gathered into graphic novel hardcover and trade paperback collections. In addition, Dynamite publishes a Shadow Annual once a year, which offers a brand new and complete stand-alone story.

In December 2012, Dynamite expanded The Shadow’s adventures by adding a new 8-issue comic book mini-series to its line, Masks. This teams the 1930’s Shadow with Dynamite’s other pulp hero-based comic book characters, The Spider, The Green Hornet and Kato, and a 1930’s Zorro (plus four other heroes of the pulp era from Dynamite’s comics line) to combat a syndicate of shrewd politicians-turned-gangsters (and their henchmen) whose criminal activities are masked by their corrupt Justice Party, which has taken control of New York City. The first issue of Masks was offered with four different regular retail color covers; additionally, four smaller print-run Retailer Incentive variant covers were also available in 1:10, 1:25, 1:50, and 1:75 quantities, respectively. In addition, for that first issue, 25 comics retailers offered special, limited-run promotional covers; each store had its name prominently displayed on a signboard as a part of their special issue’s front cover, creating 25 additional variant covers. Eight more special hand-drawn covers were also created in very limited quantities; these offered detailed color sketches drawn directly on each copy’s front cover; these eight original art variants are very expensive and signed and numbered by their respective artists. The completed storyline of this eight-issue Masks mini-series was then collected and published by Dynamite as a single trade paperback graphic novel.

After Masks, Dynamite added another Shadow 8-issue mini-series to its comics line, Shadow Year One (consciously copying Frank Miller‘s Batman: Year One), which also offered four different retail covers on every issue by four different artists, as well as additional, shorter print-run Retailer Incentive variants of those covers (as described above). Set against the backdrop of the early years of the Great Depression, the series depicts The Shadow’s early adventures fighting crime in New York City during his first year home from abroad.

Following this, another Shadow mini-series was then introduced into Dynamite’s comics line, The Shadow/Green Hornet: Dark Nights, which teams The Shadow and Green Hornet to defeat a dire threat to the entire world; unlike Dynamite’s previous Shadow titles, this 5-issue mini-series is produced with only three different retail covers and two very pricey, very low print-run Retailer Incentive covers for each issue (the kick-off first issue offered five retail covers).

In early October of 2013 Dynamite Entertainment added another Shadow title, The Shadow Now. to its line of pulp hero comics. This 6-issue mini-series continues the night master’s crime-fighting adventures, but the story line is now set in our modern era. Both standard and regular Retailer Incentive alternate covers are offered, but with fewer variants for each issue. For the very first issue, however, just like the Masks mini-series, various comics retailers offered their own special, limited-run variant front cover. The artwork used was the same, but each retailer now had their name prominently printed on a background billboard, creating a specific variant #1 cover.

Continuing this trend of The Shadow as a modern comic book hero, Go Hero teamed up with Executive Replicas and released on August 8, 2012 a limited run, red scarfed comics version of the character as a 1:6 scale (12-inch) collectible figure.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Shadow