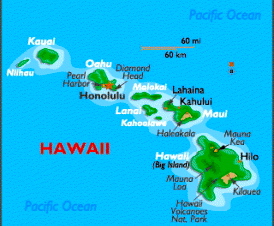

Hawaii

History of Hawaii

- (300 – 700) Polynesian settlers arrived from Marquesas

- (1627) Spanish sailors visited Hawaii

- (1778) British Captain, James Cook, discovered Hawaiian islands, named them Sandwich Islands

- (1779) Captain Cook killed at Kealakekua

- (1780’s) Many Hawaiians killed by disease brought by European and U. S. trading ships

- (1782) King Kamehameha I gained control in northern Island of Hawaii; began conquest of other islands

- (1794) Hawaii placed under protectorate of Great Britain

- (1795) King Kamehameha I unified Hawaii

1800’s

- (1813) Spanish advisor to King Kamehameha, Don Francisco de Paula y Marin, introduced coffee and pineapple to Hawaii

- (1815) Attempt by Russian soldiers to build fort failed

- (1819) King Kamehameha died; son Liholiho became Kemehameha II; he abolished local religion

- (1820) Christian missionaries arrived

- (1824) King Kamehameha II died in London

- (1825) Kauikeaouli ascended to throne as Kamehameha III

- (1826) U. S. and Hawaii entered into treaty of friendship, commerce and navigation

- (1829) First coffee planted in Kona

- (1831) Catholic missionaries forced to leave or be imprisoned

- (1835) First sugar plantation established in Koloa

- (1839) Roman Catholics received religious freedom

- (1840) Hawaii adopted first constitution

- (1842) First House of Representatives met

- (1843) Lord George Paulet seized Hawaii for England; Great Britain and France agreed Sandwich Islands would be an independent State

- (1846) Construction of Washington Place (governor’s residence) completed

- (1848) Kamehameha III divided land between King, nobility and commoners

- (1849) Invasion attempt by French Admiral Legoarant de Tromelin failed

- (1852) First steam-propelled ship used for inter-island service; first Chinese contract workers arrived

- (1853) Smallpox epidemic killed over 5,000

- (1854) Kamehameha III died; Alexander Liholiho assumed throne as Kamehameha IV

- (1863) Kamehameha IV died; Prince Lot Kapuaiwa assumed throne as Kamehameha V

- (1864) Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) sailed into Honolulu Harbor

- (1868) First Japanese contract workers arrived

- (1872) King Kamehameha V died

- (1873) William Lunalilo elected King

- (1874) Supreme Court of Hawaii moved to Ali’iolani; King Lunalilo died; David Kalakuau became King

- (1878) First telephone operated; Portuguese arrived from Azores

- (1879) First locomotive operated on Maui

- (1881) Macadamia nuts introduced to Hawaii

- (1885) First pineapples were planted

- (1886) Electricity arrived

- (1891) King Kalakaua died; Lydia Kamaka’eha became Queen Lili’uokalani

- (1893) Monarchy overthrown by government ministers, planters and businessmen

- (1894) Republic of Hawaii established

The human history of Hawaii includes phases of early Polynesian settlement, British arrival, unification, Euro-American and Asian immigrators, the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy, a brief period as the Republic of Hawaii, and admission to the United States as Hawaii Territory and then as the state of Hawaii.

The human history of Hawaii includes phases of early Polynesian settlement, British arrival, unification, Euro-American and Asian immigrators, the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy, a brief period as the Republic of Hawaii, and admission to the United States as Hawaii Territory and then as the state of Hawaii.

Discovery and settlement – Main article: Ancient Hawaiʻi

The earliest settlements in the Hawaiian Islands were made by Polynesians who traveled to Hawaii using large double-hulled canoes. They brought with them pigs, dogs, chickens, taro, sweet potatoes, coconut, banana, and sugarcane.

There are several theories regarding migration to Hawaii. The “one-migration” theory suggests a single settlement. A variation on the one-migration theory instead suggests a single, continuous settlement period. A “multiple migration” theory suggests that there was a first settlement by a group called Menehune (settlers from the Marquesas Islands), and then a second settlement by the Tahitians.

On January 18, 1778 Captain James Cook and his crew, while attempting to discover the Northwest Passage between Alaska and Asia, were surprised to find the Hawaiian islands so far north in the Pacific. He named them the “Sandwich Islands”, after the fourth Earl of Sandwich. After the discovery by Cook, other Europeans and Americans came to the Sandwich Islands.

It is said by several that the Spanish made it two centuries before. Juan de Gaitán is said to have arrived to Hawaii in 1555. There are Spanish maps of the era in which islands are shown in Hawaii latitude, but 10° further east. The first sea chart that would prove this is dated 1551, signed by Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, Italian and French cartographers, which it is shown an archipelago located at points close to the place Hawaii occupies on the globe.

Formation of the Hawaiian Kingdom

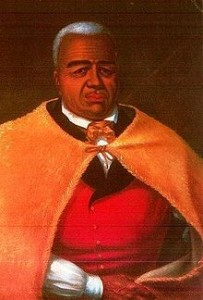

Kamehameha I unified the islands

Kamehameha I unified the islands

The islands were united under a single ruler, Kamehameha I, for the first time in 1810 with the help of foreign weapons and advisors. The monarchy then adopted a flag similar to the one used today by the State of Hawaii present flag, with the Union Flag in the canton (top quarter next to the flagpole) and eight horizontal stripes (alternating white, red, blue, from the top), representing the eight major islands of Hawaii.

In May 1819, Prince became King Kamehameha II. Under pressure from his co-regent and stepmother, Kaʻahumanu, he abolished the kapu system that had ruled life in the islands. He signaled this revolutionary change by sitting down to eat with Kaʻahumanu and other women of chiefly rank, an act forbidden under the old religious system—see ʻAi Noa.Kekuaokalani, a cousin who thought he was to share power with Liholiho, organized supporters of the kapu system, but his forces were defeated by Kaʻahumanu and Liholiho in December 1819 at the battle of Kuamoʻo.

Imperial Russia

In 1815 the Russian empire affected the islands when Georg Anton Schäffer, agent of the Russian-American Company, came to retrieve goods seized by Kaumualiʻi, chief of Kauaʻiisland. Kaumualiʻi signed a treaty making Tsar Alexander I protectorate over Kauaʻi. From 1817 to 1853 Fort Elizabeth, near the Waimea River, was one of three Russian forts on the island.

The French – Main article: The French Incident

In the early kingdom, Protestant ministers convinced Hawaiian rulers to make Catholicism illegal, deport French priests, and imprison Native Hawaiian Catholic converts.

In 1839 Captain Laplace of the French frigate Artémise sailed to Hawaii. Under the threat of war, King Kamehameha III signed the Edict of Toleration on July 17, 1839 and paid $20,000 in compensation for the deportation of the priests and the incarceration and torture of converts, agreeing to Laplace’s demands. The kingdom proclaimed: That the Catholic worship be declared free, throughout all the dominions subject to the king of the Sandwich Islands; the members of this religious faith shall enjoy in them the privileges granted to Protestants.

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Honolulu returned and Kamehameha III donated land for them to build a church as reparation. Main article: The French Invasion (1849)

In August 1849, French admiral Louis Tromelin arrived in Honolulu Harbor with La Poursuivante and Gassendi. De Tromelin made ten demands to King Kamehameha III on August 22, mainly that full religious rights be given to Catholics, (the ban on Catholicism had been lifted, but Catholics still enjoyed only partial religious rights). On August 25 the demands had not been met. After a second warning was made to the civilians, French troops overwhelmed the skeleton force and captured Honolulu Fort, spiked the coastal guns and destroyed all other weapons they found (mainly muskets and ammunition). They raided government buildings and general property in Honolulu, causing $100,000 in damages. After the raids the invasion force withdrew to the fort. De Tromelin eventually recalled his men and left Hawaii on September 5.

British – Main article: Paulet Affair (1843)

On February 10, 1843, Lord George Paulet on the Royal Navy warship HMS Carysfort entered Honolulu Harbor and demanded that King Kamehameha III cede the Hawaiian Islands to the British Crown. Under the guns of the frigate, Kamehameha stepped down under protest. Kamehameha III surrendered to Paulet on February 25, writing:

“Where are you, chiefs, people, and commons from my ancestors, and people from foreign lands?’ Hear ye! I make known to you that I am in perplexity by reason of difficulties into which I have been brought without cause, therefore I have given away the life of our land. Hear ye! but my rule over you, my people, and your privileges will continue, for I have hope that the life of the land will be restored when my conduct is justified. Done at Honolulu, Oahu, this 25th day of February, 1843. Kamehameha III. Kekauluohi.”

Gerrit P. Judd, a missionary who had become the Minister of Finance, secretly sent envoys to the United States, France and Britain, to protest Paulet’s actions. The protest was forwarded to Rear Admiral Richard Darton Thomas, Paulet’s commanding officer, who arrived at Honolulu harbor on July 26, 1843 on HMS Dublin. Thomas repudiated Paulet’s actions, and on July 31, 1843, restored the Hawaiian government. In his restoration speech, Kamehameha declared that “Ua mau ke ea o ka ʻāina i ka pono”, the motto of the future State of Hawaii translated as “The life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness.”

Kamehameha family

Dynastic rule by the Kamehameha family ended in 1872 with the death of Kamehameha V. After the short reign of Lunalilo, the House of Kalākaua came to the throne. These transitions were by election of candidates of noble birth. Princess Ka’iulani tried very hard to prevent her country from becoming part of the United States.

United States

The Reciprocity Treaty of 1875 between the Kingdom of Hawaii and the United States allowed for duty-free importation of Hawaiian sugar (from sugarcane) into the United States beginning in 1876. This promoted sugar plantation agriculture. In exchange, Hawai’i ceded Pearl Harbor, including Ford Island (in Hawaiian, Moku’ume’ume), together with its shore for four or five miles back, free of cost to the U.S. The U. S. demanded this area based on an 1873 report commissioned by the U. S. Secretary of War. This treaty explicitly acknowledged Hawai’i as a sovereign nation.

Although the treaty also included duty-free importation of rice, which was by this time becoming a major crop in the abandoned taro patches in the wetter parts of the islands, it was the influx of immigrants from Asia (first Chinese, and later Japanese) needed to support the escalating sugar industry that provided the impetus for expansion of rice growing. High water requirements for growing sugarcane resulted in extensive water works projects on all of the major islands to divert streams from the wet windward slopes to the dry lowlands.

Hawaiian revolutions – Main articles: Overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Republic of Hawaii, and Hawaiian Revolutions

Several rebellions and revolutions challenged the governments of the Kingdom and Republic of Hawaii during the late 19th century.

Rebellion of 1887

In 1887, a group of cabinet officials and advisors to King David Kalākaua and an armed militia forced the king to promulgate what is known as the Bayonet Constitution. The impetus given for the new constitution was the frustration of the Reform Party (also known as the Missionary Party) with growing debts, spending habits of the King, and general governance. It was specifically triggered by a failed attempt by Kalākaua to create a Polynesian Federation, and accusations of an opium bribery scandal. The 1887 constitution stripped the monarchy of much of its authority, imposed significant income and property requirements for voting, and completely disenfranchised all Asians from voting. When Kalākaua died in 1891 during a visit to San Francisco, his sister Liliʻuokalani assumed the throne.

Queen Liliʻuokalani in her autobiography called her brother’s reign “a golden age materially for Hawaii.” Native Hawaiians felt the 1887 constitution was imposed by a minority of the foreign population because of the king’s refusal to renew the Reciprocity Treaty, which now included an amendment that would have allowed the US Navy to have a permanent naval base at Pearl Harbor in Oʻahu, and the king’s foreign policy. According to bills submitted by the King to the Hawaiian parliament, the King’s foreign policy included an alliance with Japan and supported other countries suffering from colonialism. Many Native Hawaiians opposed US military presence in their country.

Wilcox Rebellions – Main article: Wilcox rebellions

A plot by Princess Liliʻuokalani was exposed to overthrow King David Kalākaua in a military coup in 1888. In 1889, a rebellion of Native Hawaiians led by Colonel Robert Wilcox attempted to replace the unpopular Bayonet Constitution and stormed ʻIolani Palace. The rebellion was crushed.

Revolution of 1893 – Main article: Overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii

US Marines at the time of the overthrow, January 1893

US Marines at the time of the overthrow, January 1893

According to Queen Liliʻuokalani, immediately upon ascending the throne, she received petitions from two-thirds of her subjects and the major Native Hawaiian political party in parliament, Hui Kalaiʻaina, asking her to proclaim a new constitution. Liliʻuokalani drafted a new constitution that would restore the monarchy’s authority and the suffrage requirements of the 1887 constitution.

In response to Liliʻuokalani’s suspected actions, a group of European and American residents formed a Committee of Safety on January 14, 1893. After a meeting of supporters, the Committee committed itself to removing the Queen and annexation to the United States.

United States Government Minister John L. Stevens summoned a company of uniformed US Marines from the USS Boston and two companies of US sailors to land and take up positions at the US Legation, Consulate, and Arion Hall on the afternoon of January 16, 1893. The Committee of Safety had claimed an “imminent threat to American lives and property.” The Provisional Government of Hawaii was established to manage the Hawaiian islands between the overthrow and expected annexation, supported by the Honolulu Rifles, a militia group which had defended the kingdom against the Wilcox rebellion in 1889. Under this pressure, Liliʻuokalani abdicated her throne. The Queen’s statement yielding authority, on January 17, 1893, also pleaded for justice:

“I Liliʻuokalani, by the Grace of God and under the Constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Queen, do hereby solemnly protest against any and all acts done against myself and the Constitutional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom by certain persons claiming to have established a Provisional Government of and for this Kingdom. That I yield to the superior force of the United States of America whose Minister Plenipotentiary, His Excellency John L. Stevens, has caused United States troops to be landed at Honolulu and declared that he would support the Provisional Government. Now to avoid any collision of armed forces, and perhaps the loss of life, I do this under protest and impelled by said force yield my authority until such time as the Government of the United States shall, upon facts being presented to it, undo the action of its representatives and reinstate me in the authority which I claim as the Constitutional Sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands.”

An immediate investigation into the events of the overthrow commissioned by President Cleveland was conducted by former Congressman James Henderson Blount. The Blount Report was completed on July 17, 1893 and concluded that “United States diplomatic and military representatives had abused their authority and were responsible for the change in government.”

Minister Stevens was recalled, and the military commander of forces in Hawaii was forced to resign his commission. President Cleveland stated “Substantial wrong has thus been done which a due regard for our national character as well as the rights of the injured people requires we should endeavor to repair the monarchy.” Cleveland further stated in his 1893 State of the Union Address and that, “Upon the facts developed it seemed to me the only honorable course for our Government to pursue was to undo the wrong that had been done by those representing us and to restore as far as practicable the status existing at the time of our forcible intervention.” Submitting the matter to Congress on December 18, 1893, after provisional President Sanford Dole refused to reinstate the Queen on Cleveland’s command, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee under chairman John Morgan continued investigation into the matter.

On February 26, 1894, the Morgan Report was submitted, contradicting the Blount Report and finding Stevens and the US troops “not guilty” of any involvement in the overthrow. The report asserted that, “The complaint by Liliʻuokalani in the protest that she sent to the President of the United States and dated the 18th day of January, is not, in the opinion of the committee, well founded in fact or in justice.” After submission of the Morgan Report, Cleveland ended any efforts to reinstate the monarchy, and conducted diplomatic relations with the Dole government. He rebuffed further entreaties from the Queen to intervene.