Battle of Franklin (1864)

Battle of Franklin 150th Anniversary (US Civil War)

The Battle of Franklin often called the “Gettysburg of the West” was one of the bloodiest battles in the bloody Civil War fought on November 30, 1864. The Confederate Army of the West led by General John B. Hood assaulted an entrenched Union army at Franklin as they waited to ford a river and get to Nashville. What followed was 5 hours of bloody carnage as the Confederates made a frontal attack on fortified positions. Union losses were over 2000 while Confederate losses were over 6000 including six generals killed. Hood limped on towards Nashville but really his army was crushed at Franklin and it was only a matter of time. The 150th Anniversary of the Battle of Franklin was held November 15-16 but the second day was cancelled due to bad weather. The following footage is from the first day which recreated the attacks near the center at the Carter House where some of the fiercest fighting took place. I had two ancestors involved in the battle on the Confederates side – my great-great grandfather and his brother. Both were wounded, my great-great grandfather having lost a leg and would have died if not for the kindness of a Franklin resident and later a Union prison guard.

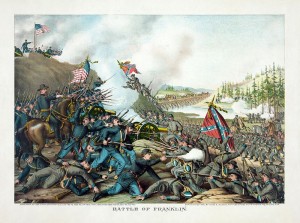

Battle of Franklin, by Kurz and Allison (1891)

Battle of Franklin, by Kurz and Allison (1891)

The Battle of Franklin was fought on November 30, 1864, at Franklin, Tennessee, as part of the Franklin-Nashville Campaign of the American Civil War. It was one of the worst disasters of the war for the Confederate States Army. Confederate Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood’s Army of Tennessee conducted numerous frontal assaults against fortified positions occupied by the Union forces under Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield and was unable to break through or to prevent Schofield from a planned, orderly withdrawal to Nashville.

The Confederate assault of six infantry divisions containing eighteen brigades with 100 regiments numbering almost 20,000 men, sometimes called the “Pickett’s Charge of the West”, resulted in devastating losses to the men and the leadership of the Army of Tennessee—fourteen Confederate generals (six killed or mortally wounded, seven wounded, and one captured) and 55 regimental commanders were casualties. After its defeat against Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas in the subsequent Battle of Nashville, the Army of Tennessee retreated with barely half the men with which it had begun the short offensive, and was effectively destroyed as a fighting force for the remainder of the war.

The 1864 Battle of Franklin was the second military action in the vicinity. The Battle of Franklin (1863) was a minor action associated with a reconnaissance in force by Confederate cavalry leader Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn on April 10.

Background – Franklin-Nashville Campaign

Following his defeat in the Atlanta Campaign, Hood had hoped to lure Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman into battle by disrupting his railroad supply line from Chattanooga to Atlanta. After a brief period in which he pursued Hood, Sherman decided instead to cut his main army off from these lines and “live off the land” in his famed March to the Sea from Atlanta to Savannah. By doing so, he would avoid having to defend hundreds of miles of supply lines against constant raids, through which he predicted he would lose “a thousand men monthly and gain no result” against Hood’s army.

Sherman’s march left the aggressive General Hood unoccupied, and his Army of Tennessee could choose several options in attacking Sherman or falling upon his rear lines. The task of defending Tennessee and the rearguard against Hood fell to Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas, commander of the Army of the Cumberland. The principal forces available in Middle Tennessee were IV Corps of the Army of the Cumberland, commanded by Maj. Gen. David S. Stanley, and XXIII Corps of the Army of the Ohio, commanded by Maj. Gen. John Schofield, with a total strength of about 30,000. Another 30,000 troops under Thomas’s command were in or moving toward Nashville.

Rather than trying to chase Sherman in Georgia, Hood decided that he would attempt a major offensive northward, even though his invading force of 39,000 would be outnumbered by the 60,000 Union troops in Tennessee. He would move north into Tennessee, defeat portions of Thomas’s army in detail before they could concentrate, seize the important manufacturing and supply center of Nashville, and continue north into Kentucky, possibly as far as the Ohio River. Hood even expected to pick up 20,000 recruits from Tennessee and Kentucky in his path of victory and then join up with Robert E. Lee’s army in Virginia, a plan that historian James M. McPherson describes as “scripted in never-never land.” Hood spent the first three weeks of November quietly supplying the Army of Tennessee in northern Alabama in preparation for his offensive.

Opposing forces – Principal Confederate Commanders

Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Cheatham

Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Cheatham

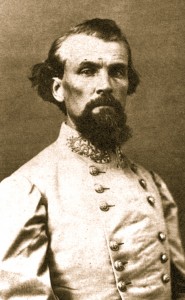

Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest

Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest

Principal Union Commanders

Further information: Confederate Order of Battle

Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood’s Army of Tennessee, at 39,000 men, constituted the second-largest remaining army of the Confederacy, ranking in strength only after Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. The army consisted of the corps of:

Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Cheatham, with divisions commanded by Maj. Gens. Patrick R. Cleburne, John C. Brown, and William B. Bate.

Lt. Gen. Stephen D. Lee, with divisions commanded by Maj. Gens. Edward “Allegheny” Johnson, Carter L. Stevenson, and Henry D. Clayton. (Only Johnson’s division played an active role at Franklin.)

Lt. Gen. Alexander P. Stewart, with divisions commanded by Maj. Gen. William W. Loring, Samuel G. French, and Edward C. Walthall.

Cavalry forces under Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, with divisions commanded by Brig. Gen. James R. Chalmers, Abraham Buford, and William H. Jackson. At Franklin, about 27,000 Confederates were engaged, primarily from the corps of Cheatham, Stewart, and Forrest, and Johnson’s division of Lee’s corp.

Union

Further information: Union order of battle

Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield, commander of the Army of the Ohio, led a force of about 27,000 consisting of:

IV Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. David S. Stanley, with divisions commanded by Brig. Gens. Nathan Kimball, George D. Wagner, and Thomas J. Wood. XXIII Corps, normally commanded by Schofield, but temporarily commanded at Franklin by Brig. Gen. Jacob D. Cox, with divisions commanded by Brig. Gens. Thomas H. Ruger and James W. Reilly.

Cavalry Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. James H. Wilson, with divisions commanded by Brig. Gen. Edward M. McCook, Edward Hatch, Richard W. Johnson, and Joseph F. Knipe.

The road to Franklin, November 21–29

The Army of Tennessee marched north from Florence, Alabama, on November 21, and indeed managed to surprise the Union forces, the two halves of which were 75 miles (121 km) apart at Pulaski, Tennessee, and Nashville. With a series of fast marches that covered 70 miles (110 km) in three days, Hood tried to maneuver between the two armies to destroy each in detail. But Union General Schofield, commanding Stanley’s IV Corps as well as his own XXIII Corps, reacted correctly with a rapid retreat from Pulaski to Columbia, which held an important bridge over the Duck River on the turnpike north. Despite suffering losses from Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s cavalry along the way, the Federals were able to reach Columbia and erect fortifications just hours before the Confederates arrived on November 24. From November 24 to 29, Schofield managed to block Hood at this crossing, and the “Battle of Columbia” was a series of mostly bloodless skirmishes and artillery bombardments while both sides re-gathered their armies.

On November 28, Thomas directed Schofield to begin preparations for a withdrawal north to Franklin. He was incorrectly expecting that Maj. Gen. A.J. Smith’s XVI Corps arrival from Missouri was imminent and he wanted the combined force to defend against Hood on the line of the Harpeth River at Franklin instead of the Duck River at Columbia. Meanwhile, early on the morning of November 29, Hood sent Cheatham’s and Stewart’s corps north on a flanking march. They crossed the Duck River at Davis’s Ford east of Columbia, while two divisions of Lee’s corps and most of the army’s artillery remained on the southern bank to deceive Schofield into thinking a general assault was planned against Columbia.

Now that Hood had outflanked him by noon on November 29, Schofield’s army was in critical danger. His command was split at that time between his supply wagons and artillery and part of the IV Corps, which he had sent to Spring Hill nearly ten miles north of Columbia, and the rest of the IV and XXIII Corps marching from Columbia to join them. In the Battle of Spring Hill that afternoon and night, Hood had a golden opportunity to intercept and destroy the Union troops and their supply wagons, as his forces had already reached the turnpike separating the Union forces by nightfall. However, because of a series of command failures along with Hood’s premature confidence that he had trapped Schofield, the Confederates failed to stop or even inflict much damage to the Union forces during the night. Both the Union infantry and supply train managed to pass Spring Hill unscathed by dawn on November 30, and soon occupied the town of Franklin 12 miles (19 km) to the north. That morning, Hood was surprised and furious to discover Schofield’s unexpected escape. After an angry conference with his subordinate commanders in which he blamed everyone but himself for the mistakes, Hood ordered his army to resume its pursuit north to Franklin.