#50. United States Capitol

The History of the United States Capitol

The United States Capitol in Washington, D.C., is among the most architecturally impressive and symbolically important buildings in the world. It has housed the meeting chambers of the Senate and the House of Representatives for almost two centuries. Since the laying of the cornerstone in 1793, the Capitol has been built, burnt, rebuilt, extended, and restored; today, it stands as a monument not only to its builders but also to the American people and their government. Learn more at: http://www.aoc.gov/cc/capitol/index.cfm.

United States Capitol Location: Washington, DC Architect: Bulfinch, Latrobe, Thornton Year: 1830

United States Capitol Location: Washington, DC Architect: Bulfinch, Latrobe, Thornton Year: 1830

Neoclassical in form, the United States Capitol achieves in articulating through architecture the principals of America’s founding fathers. Think that’s a load of mumbo jumbo? Then consider this: at time of completion the Capitol boasted the largest cast iron dome ever constructed, designed by an often forgotten fourth architect on the project, Mr. Thomas U. Walter.

History of Washington, D.C. and List of National Historic Landmarks in Washington, D.C.

The eastern side of the United States Capitol in 2013

The eastern side of the United States Capitol in 2013

Prior to establishing the nation’s capital in Washington, D.C., the United States Congressand its predecessors had met in Philadelphia (Independence Hall and Congress Hall), New York City (Federal Hall), and a number of other locations (Maryland State House in Annapolis, Maryland, Nassau Hall in Princeton, New Jersey). In September 1774, the First Continental Congress brought together delegates from the colonies in Philadelphia, followed by the Second Continental Congress, which met from May 1775 to March 1781.

After adopting the Articles of Confederation, the Congress of the Confederation was formed and convened in Philadelphia from March 1781 until June 1783, when a mob of angry soldiers converged upon Independence Hall, demanding payment for their service during the American Revolutionary War. Congress requested that John Dickinson, the governor of Pennsylvania, call up the militia to defend Congress from attacks by the protesters. In what became known as the Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783, Dickinson sympathized with the protesters and refused to remove them from Philadelphia. As a result, Congress was forced to flee to Princeton, New Jersey, on June 21, 1783, and met in Annapolis, Maryland and Trenton, New Jersey before ending up in New York City.

The United States Congress was established upon ratification of the United States Constitution and formally began on March 4, 1789. New York City remained home to Congress until July 1790, when the Residence Act was passed to pave the way for a permanent capital. The decision to locate the capital was contentious, but Alexander Hamilton helped broker a compromise in which the federal government would take on war debt incurred during the American Revolutionary War, in exchange for support from northern states for locating the capital along the Potomac River. As part of the legislation, Philadelphia was chosen as a temporary capital for ten years (until December 1800), until the nation’s capital in Washington, D.C. would be ready.

Pierre (Peter) Charles L’Enfant was given the task of creating the city plan for the new capital city. L’Enfant chose Jenkins Hill as the site for the Capitol building, with a grand boulevard connecting it with the President’s House, and a public space stretching westward to the Potomac River. In reviewing L’Enfant’s plan, Thomas Jefferson insisted the legislative building be called the “Capitol” rather than “Congress House”. The word “Capitol” comes from Latin and is associated with the Roman temple to Jupiter Optimus Maximus on Capitoline Hill. In addition to coming up with a city plan, L’Enfant had been tasked with designing the Capitol and President’s House, however he was dismissed in February 1792 over disagreements with President George Washington and the commissioners, and there were no plans at that point for the Capitol.

Design Competition

Design for the U.S. Capitol, “An Elevation for a Capitol,” by James Diamond was one of many submitted in the 1792 contest, but not selected.

Design for the U.S. Capitol, “An Elevation for a Capitol,” by James Diamond was one of many submitted in the 1792 contest, but not selected.

In spring 1792, Thomas Jefferson proposed a design competition to solicit designs for the Capitol and the President’s House, and set a four-month deadline. The prize for the competition was $500 and a lot in the federal city. At least ten individuals submitted designs for the Capitol; however the drawings were regarded as crude and amateurish, reflecting the level of architectural skill present in the United States at the time. The most promising of the submissions was by Stephen Hallet, a trained French architect. However, Hallet’s designs were overly fancy, with too much French influence, and were deemed too costly.

A late entry by amateur architect William Thornton was submitted on January 31, 1793, to much praise for its “Grandeur, Simplicity, and Beauty” by Washington, along with praise from Thomas Jefferson. Thornton was inspired by the east front of the Louvre, as well as the Paris Pantheon for the center portion of the design. Thornton’s design was officially approved in a letter, dated April 5, 1793, from Washington. In an effort to console Hallet, the commissioners appointed him to review Thornton’s plans, develop cost estimates, and serve as superintendent of construction. Hallet proceeded to pick apart and make drastic changes to Thornton’s design, which he saw as costly to build and problematic. In July 1793, Jefferson convened a five-member commission, bringing Hallet and Thornton together, along with James Hoban, to address problems with and revise Thornton’s plan. Hallet suggested changes to the floor plan, which could be fitted within the exterior design by Thornton. The revised plan was accepted, except that Jefferson and Washington insisted on an open recess in the center of the East front, which was part of Thornton’s original plan.

The original design by Thornton was later modified by Benjamin Henry Latrobe and then Charles Bulfinch. The current dome and the House and Senate wings were designed by Thomas U. Walter and August Schoenborn, a German immigrant, and were completed under the supervision of Edward Clark.

Construction

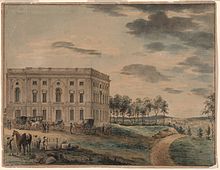

The Capitol when first occupied by Congress (painting circa 1800 by William Russell Birch)

The Capitol when first occupied by Congress (painting circa 1800 by William Russell Birch)

L’Enfant secured the lease of quarries at Wigginton Island and along Aquia Creek in Virginia for use in the foundations and outer walls of the Capitol in November 1791. Surveying was underway soon after the Jefferson conference plan for the Capitol was accepted. On September 18, 1793 George Washington, along with eight other Freemasons dressed in masonic regalia, laid the cornerstone, which was made by silversmith Caleb Bentley.

Construction proceeded with Hallet working under supervision of James Hoban, who was also busy working on construction of the White House. Despite the wishes of Jefferson and the President, Hallet went ahead anyway and modified Thornton’s design for the East front and created a square central court that projected from the center, with flanking wings which would house the legislative bodies. Hallet was dismissed by Jefferson on November 15, 1794. George Hadfield was hired on October 15, 1795 as superintendent of construction, but resigned three years later in May 1798, due to dissatisfaction with Thornton’s plan and quality of work done thus far.

The Senate wing was completed in 1800, while the House wing was completed in 1811. However, the House of Representatives moved into the House wing in 1807. Though the building was incomplete, the Capitol held its first session of United States Congress on November 17, 1800. The legislature was moved to Washington prematurely, at the urging of President John Adams in hopes of securing enough Southern votes to be re-elected for a second term as president.

Early religious usage

In its early days, the Capitol building was not only used for governmental functions. On Sundays, church services were regularly held there – a practice that continued until after the Civil War. According to the US Library of Congress exhibit “Religion and the Founding of the American Republic” “It is no exaggeration to say that on Sundays in Washington during the administrations of Thomas Jefferson (1801–1809) and of James Madison (1809–1817) the state became a church. Within a year of his inauguration, Jefferson began attending church services in the House of Representatives. Madison followed Jefferson’s example, although unlike Jefferson, who rode on horseback to church in the Capitol, Madison came in a coach and four. Worship services in the House—a practice that continued until after the Civil War—were acceptable to Jefferson because they were nondiscriminatory and voluntary. Preachers of every Protestant denomination appeared. (Catholic priests began officiating in 1826).”

War of 1812

The Capitol after the burning of Washington, D.C. in the War of 1812 (painting 1814 by George Munger)

The Capitol after the burning of Washington, D.C. in the War of 1812 (painting 1814 by George Munger)

Not long after the completion of both wings, the Capitol was partially burned by the British on August 24, 1814, during the War of 1812. George Bomford, and Joseph Gardner Swift, both military engineers, were called upon to help rebuild the Capitol. Reconstruction began in 1815 and was completed by 1819. Construction continued through to 1826, with the addition of the center Rotunda area and the first dome of the Capitol. Latrobe is principally connected with the original construction and many innovative interior features; his successor, Bulfinch, also played a major role, such as the design of the first dome.

The House and Senate Wings

Daguerreotype of east side of the Capitol (1846 by John Plumbe)

Daguerreotype of east side of the Capitol (1846 by John Plumbe)

By 1850, it became clear that the Capitol could not accommodate the growing number of legislators arriving from newly admitted states. A new design competition was held, and President Millard Fillmore appointed Philadelphia architect Thomas U. Walter to carry out the expansion. Two new wings were added – a new chamber for the House of Representatives on the south side, and a new chamber for the Senate on the north.

When the Capitol was expanded in the 1850’s, some of the construction labor was carried out by slaves “who cut the logs, laid the stones and baked the bricks.” The original plan was to use workers brought in from Europe; however, there was a poor response to recruitment efforts, and African Americans—free and slave—comprised the majority of the work force.

United States Capitol dome

The 1850 expansion more than doubled the length of the Capitol, dwarfing the original, timber-framed 1818 dome. In 1855, the decision was made to tear it down and replace it with the “wedding-cake style” cast-iron dome that stands today. Also designed by Walter, the new dome stood three times the height of the original dome and 100 feet (30 m) in diameter, yet had to be supported on the existing masonry piers. Like Mansart‘s dome at Les Invalides (which he had visited in 1838), Walter’s dome is double, with a large oculus in the inner dome, through which is seen The Apotheosis of Washington painted on a shell suspended from the supporting ribs, which also support the visible exterior structure and the tholos that supports Freedom, a colossal statue that was added to the top of the dome in 1863. This statue was cast by a slave named Philip Reid. The weight of the cast iron for the dome has been published as 8,909,200 pounds (4,041,100 kg).

Later expansion

US Senate chamber (photo circa 1873)

US Senate chamber (photo circa 1873)

When the Capitol’s new dome was finally completed, its massive visual weight, in turn, overpowered the proportions of the columns of the East Portico, built in 1828. The East Front of the Capitol building was rebuilt in 1904, following a design of the architects Carrère and Hastings, who also designed the Senate and House office buildings.

The next major expansion to the Capitol started in 1958, with a 33.5 feet (10.2 m) extension of the East Portico. During this project, in 1960 the dome underwent its last restoration. A marble duplicate of the sandstone East Front was built 33.5 feet (10.2 m) from the old Front. (In 1962, a connecting extension incorporated what formerly was an outside wall as an inside wall.) In the process, the Corinthian columns were removed. It was not until 1984 that landscape designer Russell Page created a suitable setting for them in a large meadow at the National Arboretum as the National Capitol Columns, where they are combined with a reflecting pool in an ensemble that reminds some visitors of Persepolis. Besides the columns, hundreds of blocks of the original stone were removed and are stored behind a National Park Service maintenance yard in Rock Creek Park.

National Capitol Columns at the National Arboretum (photo 2008)

National Capitol Columns at the National Arboretum (photo 2008)

On December 19, 1960, the Capitol was declared a National Historic Landmark by the National Park Service. The building was ranked #6 in a 2007 survey conducted for the American Institute of Architects‘ “America’s Favorite Architecture” list. The Capitol draws heavily from other notable buildings, especially churches and landmarks in Europe, including the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican and St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. On the roofs of the Senate and House Chambers are flagpoles that fly the U.S. flag when either is in session. On September 18, 1993, to commemorate the Capitol’s bicentennial, the Masonic ritual cornerstone laying with George Washington was reenacted. Strom Thurmond was one of the Freemason politicians who took part in the ceremony.

On June 20, 2000, ground was broken for the Capitol Visitor Center, which subsequently opened on December 2, 2008. From 2001 through 2008, the East Front of the Capitol (site of most presidential inaugurations until Ronald Reagan began a new tradition in 1981) was the site of construction for this massive underground complex, designed to facilitate a more orderly entrance for visitors to the Capitol. Prior to the center being built, visitors to the Capitol had to queue on the parking lot and ascend the stairs, whereupon entry was made through the massive sculpted Columbus Doors, through a small narthex cramped with security, and thence directly into the Rotunda. The new underground facility provides a grand entrance hall, a visitors theater, room for exhibits, and dining and restroom facilities, in addition to space for building necessities such as an underground service tunnel.

$20 million in work around the base of the dome was done, and before the August 2012 recess, the Senate Appropriations Committee voted to spend $61 million to repair the exterior of the dome, which has at least 1,300 cracks that have led to rusting inside. The House wants to spend less on government operations, making it unlikely the money will be approved.