#39. Golden Gate Bridge

Building The Golden Gate Bridge

Golden Gate Bridge Location: San Francisco, CA. Architect: Joseph Strauss, Irving Morrow, and Charles Ellis Year: 1937

Golden Gate Bridge Location: San Francisco, CA. Architect: Joseph Strauss, Irving Morrow, and Charles Ellis Year: 1937

While we’re on the subject of bridges, let’s note the Golden Gate Bridge. A symbol of San Francisco and a marvel of the modern world, the Golden Gate remains the second-longest suspension bridge in the United States. The other takes you to Staten Island, proving that sometimes (but just sometimes) second place is the better place.

The Golden Gate Bridge is a suspension bridge spanning the Golden Gate strait, the mile-wide three mile long channel between San Francisco Bay and the Pacific Ocean. The structure links the U.S. city of San Francisco, on the northern tip of the San Francisco Peninsula, to Marin County. It is one of the most internationally recognized symbols of San Francisco, California, and the United States. It has been declared one of the Wonders of the Modern World by the American Society of Civil Engineers.

The Frommers travel guide considers the Golden Gate Bridge “possibly the most beautiful, certainly the most photographed, bridge in the world.” It opened in 1937 and had until 1964 the longest suspension bridge main span in the world, at 4,200 feet (1,280 m).

History – Ferry Service

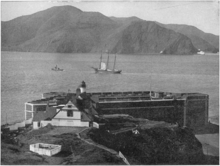

Golden Gate with Fort Point in foreground, c. 1891

Golden Gate with Fort Point in foreground, c. 1891

Before the bridge was built, the only practical short route between San Francisco and what is now Marin County was by boat across a section of San Francisco Bay. Ferry service began as early as 1820, with regularly scheduled service beginning in the 1840’s for purposes of transporting water to San Francisco.

The Sausalito Land and Ferry Company service, launched in 1867, eventually became the Golden Gate Ferry Company, a Southern Pacific Railroad subsidiary, the largest ferry operation in the world by the late 1920s. Once for railroad passengers and customers only, Southern Pacific’s automobile ferries became very profitable and important to the regional economy. The ferry crossing between the Hyde Street Pier in San Francisco and Sausalito in Marin County took approximately 20 minutes and cost US$1.00 per vehicle, a price later reduced to compete with the new bridge. The trip from the San Francisco Ferry Building took 27 minutes.

Many wanted to build a bridge to connect San Francisco to Marin County. San Francisco was the largest American city still served primarily by ferry boats. Because it did not have a permanent link with communities around the bay, the city’s growth rate was below the national average. Many experts said that a bridge couldn’t be built across the 6,700 ft (2,042 m) strait. It had strong, swirling tides and currents, with water 372 ft (113 m) deep at the center of the channel, and frequent strong winds. Experts said that ferocious winds and blinding fogs would prevent construction and operation.

Conception

Although the idea of a bridge spanning the Golden Gate was not new, the proposal that eventually took hold was made in a 1916 San Francisco Bulletin article by former engineering student James Wilkins. San Francisco’s City Engineer estimated the cost at $100 million, impractical for the time, and fielded the question to bridge engineers of whether it could be built for less. One who responded, Joseph Strauss, was an ambitious engineer and poet who had, for hisgraduate thesis, designed a 55-mile (89 km) long railroad bridge across the Bering Strait. At the time, Strauss had completed some 400 drawbridges—most of which were inland—and nothing on the scale of the new project. Strauss’s initial drawings were for a massive cantilever on each side of the strait, connected by a central suspension segment, which Strauss promised could be built for $17 million.

Local authorities agreed to proceed only on the assurance that Strauss alter the design and accept input from several consulting project experts. A suspension-bridge design was considered the most practical, because of recent advances in metallurgy.

Strauss spent more than a decade drumming up support in Northern California. The bridge faced opposition – including litigation – from many sources. The Department of War was concerned that the bridge would interfere with ship traffic; the navy feared that a ship collision or sabotage to the bridge could block the entrance to one of its main harbors. Unions demanded guarantees that local workers would be favored for construction jobs. Southern Pacific Railroad, one of the most powerful business interests in California, opposed the bridge as competition to its ferry fleet and filed a lawsuit against the project, leading to a mass boycott of the ferry service.

In May 1924, Colonel Herbert Deakyne held the second hearing on the Bridge on behalf of the Secretary of War in a request to use federal land for construction. Deakyne, on behalf of the Secretary of War, approved the transfer of land needed for the bridge structure and leading roads to the “Bridging the Golden Gate Association” and both San Francisco County and Marin County, pending further bridge plans by Strauss. Another ally was the fledgling automobile industry, which supported the development of roads and bridges to increase demand for automobiles.

The bridge’s name was first used when the project was initially discussed in 1917 by M.M. O’Shaughnessy, city engineer of San Francisco, and Strauss. The name became official with the passage of the Golden Gate Bridge and Highway District Act by the state legislature in 1923.

Preliminary discussions leading to the eventual building of the Golden Gate Bridge were held on January 13, 1923, at a special convention in Santa Rosa, CA. The Santa Rosa Chamber was charged with considering the necessary steps required to foster the construction of a bridge across the Golden Gate by then Santa Rosa Chamber President Frank Doyle (the street Doyle Drive leading up to the bridge is named after him). On June 12, the Santa Rosa Chamber voted to endorse the actions of the “Bridging the Golden Gate Association” by attending the meeting of the Boards of Supervisors in San Francisco on June 23 and by requesting that the Board of Supervisors of Sonoma County also attend. By 1925, the Santa Rosa Chamber had assumed responsibility for circulating bridge petitions as the next step for the formation of the Golden Gate Bridge.

Design

South tower seen from walkway, with Art Deco elements

South tower seen from walkway, with Art Deco elements

Strauss was chief engineer in charge of overall design and construction of the bridge project. However, because he had little understanding or experience with cable-suspension designs, responsibility for much of the engineering and architecture fell on other experts. Strauss’ initial design proposal (two double cantilever spans linked by a central suspension segment) was unacceptable from a visual standpoint. The final graceful suspension design was conceived and championed by New York’s Manhattan Bridge designer Leon Moisseiff.

Irving Morrow, a relatively unknown residential architect, designed the overall shape of the bridge towers, the lighting scheme, and Art Deco elements such as the tower decorations, streetlights, railing, and walkways. The famous International Orange color was originally used as a sealant for the bridge. The US Navy had wanted it to be painted with black and yellow stripes to ensure visibility by passing ships.

Senior engineer Charles Alton Ellis, collaborating remotely with Moisseiff, was the principal engineer of the project. Moisseiff produced the basic structural design, introducing his “deflection theory” by which a thin, flexible roadway would flex in the wind, greatly reducing stress by transmitting forces via suspension cables to the bridge towers. Although the Golden Gate Bridge design has proved sound, a later Moisseiff design, the original Tacoma Narrows Bridge, collapsed in a strong windstorm soon after it was completed, because of an unexpected aeroelastic flutter. Ellis was also tasked with designing a “bridge within a bridge” in the southern abutment, to avoid the need to demolish Fort Point, a pre-Civil War masonry fortification viewed, even then, as worthy of historic preservation. He penned a graceful steel arch spanning the fort and carrying the roadway to the bridge’s southern anchorage.

Ellis was a Greek scholar and mathematician who at one time was a University of Illinois professor of engineering despite having no engineering degree (he eventually earned a degree in civil engineering from University of Illinois prior to designing the Golden Gate Bridge and spent the last twelve years of his career as a professor at Purdue University). He became an expert in structural design, writing the standard textbook of the time. Ellis did much of the technical and theoretical work that built the bridge, but he received none of the credit in his lifetime. In November 1931, Strauss fired Ellis and replaced him with a former subordinate, Clifford Paine, ostensibly for wasting too much money sending telegrams back and forth to Moisseiff. Ellis, obsessed with the project and unable to find work elsewhere during the Depression, continued working 70 hours per week on an unpaid basis, eventually turning in ten volumes of hand calculations.

With an eye toward self-promotion and posterity, Strauss downplayed the contributions of his collaborators who, despite receiving little recognition or compensation, are largely responsible for the final form of the bridge. He succeeded in having himself credited as the person most responsible for the design and vision of the bridge. Only much later were the contributions of the others on the design team properly appreciated. In May 2007, the Golden Gate Bridge District issued a formal report on 70 years of stewardship of the famous bridge and decided to give Ellis major credit for the design of the bridge.

Finance

The Golden Gate Bridge and Highway District, authorized by an act of the California Legislature, was incorporated in 1928 as the official entity to design, construct, and finance the Golden Gate Bridge. However, after the Wall Street Crash of 1929, the District was unable to raise the construction funds, so it lobbied for a $30 million bond measure. The bonds were approved in November 1930, by votes in the counties affected by the bridge. The construction budget at the time of approval was $27 million. However, the District was unable to sell the bonds until 1932, when Amadeo Giannini, the founder of San Francisco–based Bank of America, agreed on behalf of his bank to buy the entire issue in order to help the local economy.

Construction

Construction began on January 5, 1933. The project cost more than $35 million, completing ahead of schedule and under budget. The Golden Gate Bridge construction project was carried out by the McClintic-Marshall Construction Co., a subsidiary of Bethlehem Steel Corporation founded by Howard H. McClintic and Charles D. Marshall, both of Lehigh University.

Some 1.2 million steel rivets hold the bridge together. This is one of those replaced during the seismic retrofit of the bridge after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake.

Some 1.2 million steel rivets hold the bridge together. This is one of those replaced during the seismic retrofit of the bridge after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake.

Strauss remained head of the project, overseeing day-to-day construction and making some groundbreaking contributions. A graduate of the University of Cincinnati, he placed a brick from his alma mater’s demolished McMicken Hall in the south anchorage before the concrete was poured. He innovated the use of movable safety netting beneath the construction site, which saved the lives of many otherwise-unprotected steelworkers. Of eleven men killed from falls during construction, ten were killed (when the bridge was near completion) when the net failed under the stress of a scaffold that had fallen. Nineteen others who were saved by the net over the course of construction became proud members of the (informal) Half Way to Hell Club.

The project was finished by April 1937, $1.3 million under budget. The Bridge Round House diner was then included in the southeastern end of the Golden Gate Bridge, adjacent to the tourist plaza which was renovated in 2012. The Bridge Round House, an Art Deco design by Alfred Finnila completed in 1938, has been popular throughout the years as a starting point for various commercial tours of the bridge and an unofficial gift shop. The diner was renovated in 2012 and the gift shop was then removed as a new, official gift shop has been included in the adjacent plaza renovations.

During the bridge work, the Assistant Civil Engineer of California Alfred Finnila had overseen the entire ironing work of the bridge as well as half of the bridge’s road work. With the death of Jack Balestreri in April 2012, all workers involved in the original construction are now deceased.

Opening festivities, 50th, and 75th anniversaries

A pedestrian poses at the old railing on opening day, 1937.

A pedestrian poses at the old railing on opening day, 1937.

The bridge-opening celebration began on May 27, 1937 and lasted for one week. The day before vehicle traffic was allowed, 200,000 people crossed by foot and roller skates. On opening day, Mayor Angelo Rossi and other officials rode the ferry to Marin, then crossed the bridge in a motorcade past three ceremonial “barriers”, the last a blockade of beauty queens who required Joseph Strauss to present the bridge to the Highway District before allowing him to pass. An official song, “There’s a Silver Moon on the Golden Gate,” was chosen to commemorate the event. Strauss wrote a poem that is now on the Golden Gate Bridge entitled “The Mighty Task is Done.” The next day, President Roosevelt pushed a button in Washington, D.C. signaling the official start of vehicle traffic over the Bridge at noon. When the celebration got out of hand, the SFPD had a small riot in the uptown Polk Gulch area. Weeks of civil and cultural activities called “the Fiesta” followed. A statue of Strauss was moved in 1955 to a site near the bridge.

In May 1987, as part of the 50th anniversary celebration, the Golden Gate Bridge district again closed the bridge to automobile traffic and allowed pedestrians to cross the bridge. However, this celebration attracted 750,000 to 1,000,000 people, and ineffective crowd control meant the bridge became congested with roughly 300,000 people, causing the center span of the bridge to flatten out under the weight. Although the bridge is designed to flex in that way under heavy loads, and was estimated not to have exceeded 40% of the yielding stress of the suspension cables, bridge officials stated that uncontrolled pedestrian access was not being considered as part of the 75th anniversary on Sunday, May 27, 2012, because of the additional law enforcement costs required “since 9/11.”

Description – Specifications

On the south side of the bridge a 36.5 inch (93 cm) wide cross-section of the cable, containing 27,572 wires, is on display.

On the south side of the bridge a 36.5 inch (93 cm) wide cross-section of the cable, containing 27,572 wires, is on display.

A view of the Golden Gate Bridge from the Marin Headlands on a foggy morning at sunrise

A view of the Golden Gate Bridge from the Marin Headlands on a foggy morning at sunrise

Until 1964, the Golden Gate Bridge had the longest suspension bridge main span in the world, at 4,200 feet (1,280.2m). Since 1964 its main span length has been surpassed by ten bridges; it now has the second longest main span in the United States, after the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge in New York City.

Total length of the Golden Gate Bridge from abutment to abutment is 8,981 feet (2,737 m).

At 746 feet (227m) above water the Golden Gate Bridge had the world’s tallest suspension towers until 1998 when bridges in Denmark and Japan were completed.

Structure

The weight of the roadway is hung from two cables that pass through the two main towers and are fixed in concrete at each end. Each cable is made of 27,572 strands of wire. There are 80,000 miles (129,000 km) of wire in the main cables. The bridge has approximately 1,200,000 total rivets.

Traffic

The bridge is part of the National Highway System, not U.S. Highway 101 or State Route 1, contrary to popular belief. The median markers between the lanes are moved to conform to traffic patterns. On weekday mornings, traffic flows mostly southbound into the city, so four of the six lanes run southbound. Conversely, on weekday afternoons, four lanes run northbound. During off-peak periods and weekends, traffic is split with three lanes in each direction, or three and two lanes with one buffer lane.

Traffic is separated by small, plastic pylons, and from 1971 through 2007, there were 16 fatalities from head-on collisions. To improve safety, the speed limit on the Golden Gate Bridge was reduced from 55 mph (89 km/h) to 45 mph (72 km/h) on October 1, 1983. Although there has been discussion concerning the installation of a movable barrier since the 1980s, only in March 2005 did the Bridge Board of Directors commit to finding funding to complete the $2 million study required prior to the installation of a movable median barrier. As of 2012, the study is still ongoing.

Visiting the bridge

The bridge is popular with pedestrians and bicyclists, and was built with walkways on either side of the six vehicle traffic lanes. Initially, they were separated from the traffic lanes by only a metal curb, but railings between the walkways and the traffic lanes were added in 2003, primarily as a measure to prevent bicyclists from falling into the roadway.

The main walkway is on the eastern side, and is open for use by both pedestrians and bicycles in the morning to mid-afternoon during weekdays (5 am to 3:30 pm), and to pedestrians only for the remaining daylight hours (until 6 pm, or 9 pm during DST). The eastern walkway is reserved for pedestrians on weekends (5 am to 6 pm, or 9 pm during DST), and is open exclusively to bicyclists in the evening and overnight, when it is closed to pedestrians. The western walkway is only open, and exclusively for bicyclists, during the hours when they are not allowed on the eastern walkway.

Bus service across the bridge is provided by two public transportation agencies: San Francisco Muni and Golden Gate Transit. Muni offers Sunday service on the 76 Marin Headlands bus line, and Golden Gate Transit runs numerous bus lines throughout the week. The southern end of the bridge, near the toll plaza and parking lot, is also accessible daily from 5:30 a.m. to midnight by Muni line 28.

Aesthetics

The Golden Gate Bridge by night, with part of downtown San Francisco visible in the background at far left

The color of the bridge is officially an orange vermillion called international orange. The color was selected by consulting architect Irving Morrow because it complements the natural surroundings and enhances the bridge’s visibility in fog. Aesthetics was the foremost reason why the first design of Joseph Strauss was rejected. Upon re-submission of his bridge construction plan, he added details, such as lighting, to outline the bridge’s cables and towers. In 1999, it was ranked fifth on the List of America’s Favorite Architecture by the American Institute of Architects.

Paintwork

The bridge was originally painted with red lead primer and a lead-based topcoat, which was touched up as required. In the mid-1960’s, a program was started to improve corrosion protection by stripping the original paint and repainting the bridge with zinc silicate primer and vinyl topcoats. Since 1990 acrylic topcoats have been used instead for air-quality reasons. The program was completed in 1995 and it is now maintained by 38 painters who touch up the paintwork where it becomes seriously corroded.