#13. Eiffel Tower

The History of the Eiffel Tower

The history of the Eiffel tower (full documentary episode).

Eiffel Tower Location: Paris, France Architect: Stephen Sauvestre Year: 1889

Eiffel Tower Location: Paris, France Architect: Stephen Sauvestre Year: 1889

Originally the entrance to the Paris World’s Fair of 1889, the Eiffel Tower has become a global icon and one of the few buildings people associate with romance. Fun fact: the observation deck allows for great views of a nearby football pitch.

The Eiffel Tower (French: La Tour Eiffel, [tuʁ ɛfɛl]) is an iron lattice tower located on the Champ de Mars in Paris. It was named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower. Erected in 1889 as the entrance arch to the 1889 World’s Fair, it has become both a global cultural icon of France and one of the most recognizable structures in the world. The tower is the tallest structure in Paris and the most-visited paid monument in the world; 7.1 million people ascended it in 2011. The tower received its 250 millionth visitor in 2010.

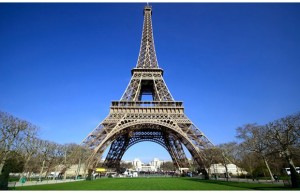

The Eiffel Tower as seen from the Champ de Mars

The Eiffel Tower as seen from the Champ de Mars

The tower stands 324 metres (1,063 ft) tall, about the same height as an 81-storey building. During its construction, the Eiffel Tower surpassed the Washington Monument to assume the title of the tallest man-made structure in the world, a title it held for 41 years, until the Chrysler Building in New York City was built in 1930. Because of the addition of the antenna atop the Eiffel Tower in 1957, it is now taller than the Chrysler Building by 17 feet (5.2 m). Not including broadcast antennas, it is the second-tallest structure in France, after the Millau Viaduct.

The tower has three levels for visitors. The third level observatory’s upper platform is at 279.11 m (915.7 ft) the highest accessible to the public in the European Union. Tickets can be purchased to ascend, by stairs or lift (elevator), to the first and second levels. The walk from ground level to the first level is over 300 steps, as is the walk from the first to the second level. Although there are stairs to the third and highest level, these are usually closed to the public and it is usually accessible only by lift. The first and second levels have restaurants.

The tower has become the most prominent symbol of both Paris and France, often in the establishing shot of films set in the city.

History – Origin

First drawing of the Eiffel Tower by Maurice Koechlin

First drawing of the Eiffel Tower by Maurice Koechlin

The design of the Eiffel Tower was originated by Maurice Koechlin and Émile Nouguier, two senior engineers who worked for the Compagnie des Etablissements Eiffel after discussion about a suitable centrepiece for the proposed 1889 Exposition Universelle, a World’s Fair which would celebrate the centennial of the French Revolution. In May 1884, Koechlin, working at home, made an outline drawing of their scheme, described by him as “a great pylon, consisting of four lattice girders standing apart at the base and coming together at the top, joined together by metal trusses at regular intervals.” Initially Eiffel himself showed little enthusiasm, but he did sanction further study of the project, and the two engineers then asked Stephen Sauvestre, the head of company’s architectural department, to contribute to the design. Sauvestre added decorative arches to the base, a glass pavilion to the first level and other embellishments. This enhanced version gained Eiffel’s support, and he bought the rights to the patent on the design which Koechlin, Nougier, and Sauvestre had taken out, and the design was exhibited at the Exhibition of Decorative Arts in the autumn of 1884 under the company name. On 30 March 1885 Eiffel presented a paper on the project to the Société des Ingiénieurs Civils; after discussing the technical problems and emphasising the practical uses of the tower, he finished his talk by saying that the tower would symbolise

“not only the art of the modern engineer, but also the century of Industry and Science in which we are living, and for which the way was prepared by the great scientific movement of the eighteenth century and by the Revolution of 1789, to which this monument will be built as an expression of France’s gratitude.”

Little happened until the beginning of 1886, when Jules Grévy was re-elected as President and Édouard Lockroy was appointed as Minister for Trade. A budget for the Exposition was passed and on 1 May Lockroy announced an alteration to the terms of the open competition which was being held for a centerpiece for the exposition, which effectively made the choice of Eiffel’s design a foregone conclusion: all entries had to include a study for a 300 m (980 ft) four-sided metal tower on the Champ de Mars. On 12 May a commission was set up to examine Eiffel’s scheme and its rivals and on 12 June it presented its decision, which was that all the proposals except Eiffel’s were either impractical or insufficiently worked out. After some debate about the exact site for the tower, a contract was finally signed on 8 January 1887. This was signed by Eiffel acting in his own capacity rather than as the representative of his company, and granted him 1.5 million francs toward the construction costs: less than a quarter of the estimated 6.5 million francs. Eiffel was to receive all income from the commercial exploitation of the tower during the exhibition and for the following twenty years. Eiffel later established a separate company to manage the tower, putting up half the necessary capital himself.

The “Artists Protest”

Caricature of Gustave Eiffel comparing the Eiffel tower to the Pyramids.

Caricature of Gustave Eiffel comparing the Eiffel tower to the Pyramids.

The projected tower had been a subject of some controversy, attracting criticism both from those who did not believe that it was feasible and also from those who objected on artistic grounds. Their objections were an expression of a longstanding debate about the relationship between architecture and engineering. This came to a head as work began at the Champ de Mars: A “Committee of Three Hundred” (one member for each metre of the tower’s height) was formed, led by the prominent architect Charles Garnier and including some of the most important figures of the French arts establishment, including Adolphe Bouguereau, Guy de Maupassant, Charles Gounod and Jules Massenet: a petition was sent to Charles Alphand, the Minister of Works and Commissioner for the Exposition, and was published by Le Temps.

“We, writers, painters, sculptors, architects and passionate devotees of the hitherto untouched beauty of Paris, protest with all our strength, with all our indignation in the name of slighted French taste, against the erection…of this useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower … To bring our arguments home, imagine for a moment a giddy, ridiculous tower dominating Paris like a gigantic black smokestack, crushing under its barbaric bulk Notre Dame, the Tour Saint-Jacques, the Louvre, the Dome of les Invalides, the Arc de Triomphe, all of our humiliated monuments will disappear in this ghastly dream. And for twenty years…we shall see stretching like a blot of ink the hateful shadow of the hateful column of bolted sheet metal”

Gustave Eiffel responded to these criticisms by comparing his tower to the Egyptian Pyramids: “My tower will be the tallest edifice ever erected by man. Will it not also be grandiose in its way ? And why would something admirable in Egypt become hideous and ridiculous in Paris ?” These criticisms were also masterfully dealt with byÉdouard Lockroy in a letter of support written to Alphand, ironically saying “Judging by the stately swell of the rhythms, the beauty of the metaphors, the elegance of its delicate and precise style, one can tell that…this protest is the result of collaboration of the most famous writers and poets of our time”, and going on to point out that the protest was irrelevant since the project had been decided upon months before and was already under construction. Indeed, Garnier had been a member of the Tower Commission that had assessed the various proposals, and had raised no objection. Eiffel was similarly unworried, pointing out to a journalist that it was premature to judge the effect of the tower solely on the basis of the drawings, that the Champ de Mars was distant enough from the monuments mentioned in the protest for there to be little risk of the tower overwhelming them, and putting the aesthetic argument for the Tower: “Do not the laws of natural forces always conform to the secret laws of harmony?”

Some of the protestors were to change their minds when the tower was built: others remained unconvinced. Guy de Maupassant supposedly ate lunch in the tower’s restaurant every day because it was the one place in Paris where the tower was not visible. Today, the Tower is widely considered to be a striking piece of structural art.

Construction

Foundations of the Eiffel Tower

Foundations of the Eiffel Tower

Eiffel Tower under construction between 1887 and 1889.

Eiffel Tower under construction between 1887 and 1889.

Work on the foundations started in January 1887. Those for the east and south legs were straightforward, each leg resting on four 2 m (6.6 ft) concrete slabs, one for each of the principal girders of each leg but the other two, being closer to the river Seine, were more complicated: each slab needed two piles installed by using compressed-air caissons 15 m (49 ft) long and 6 m (20 ft) in diameter driven to a depth of 22 m (72 ft) to support the concrete slabs, which were 6 m (20 ft) thick. Each of these slabs supported a block built of limestone each with an inclined top to bear a supporting shoe for the ironwork. Each shoe was anchored into the stonework by a pair of bolts 10 cm (4 in) in diameter and 7.5 m (25 ft) long. The foundations were complete by 30 June and the erection of the ironwork began. The very visible work on-site was complemented by the enormous amount of exacting preparatory work that was entailed: the drawing office produced 1,700 general drawings and 3,629 detailed drawings of the 18,038 different parts needed. The task of drawing the components was complicated by the complex angles involved in the design and the degree of precision required: the position of rivet holes was specified to within 0.1 mm (0.04 in) and angles worked out to one second of arc. The finished components, some already riveted together into sub-assemblies, arrived on horse-drawn carts from the factory in the nearby Parisian suburb of Levallois-Perret and were first bolted together, the bolts being replaced by rivets as construction progressed. No drilling or shaping was done on site: if any part did not fit it was sent back to the factory for alteration. In all there were 18,038 pieces joined by two and a half million rivets.

At first the legs were constructed as cantilevers but about halfway to the first level construction was paused in order to construct a substantial timber scaffold. This caused a renewal of the concerns about the structural soundness of the project, and sensational headlines such as “Eiffel Suicide!” and “Gustave Eiffel has gone mad: he has been confined in an Asylum” appeared in the popular press. At this stage a small “creeper” crane was installed in each leg, designed to move up the tower as construction progressed and making use of the guides for the lifts which were to be fitted in each leg. The critical stage of joining the four legs at the first level was complete by March 1888. Although the metalwork had been prepared with the utmost precision, provision had been made to carry out small adjustments in order to precisely align the legs: hydraulic jacks were fitted to the shoes at the base of each leg, each capable of exerting a force of 800 tonnes, and in addition the legs had been intentionally constructed at a slightly steeper angle than necessary, being supported by sandboxes on the scaffold.

Although construction involved 300 on-site employees, only one person died thanks to Eiffel’s stringent safety precautions and use of movable stagings, guard-rails, and screens.

Inauguration and the 1889 Exposition

The 1889 Exposition Universelle for which the Eiffel Tower was built. For over forty years after its construction, the Eiffel Tower was the tallest man-made structure in the world.

The 1889 Exposition Universelle for which the Eiffel Tower was built. For over forty years after its construction, the Eiffel Tower was the tallest man-made structure in the world.

The main structural work was completed at the end of March 1889 and on the 31st Eiffel celebrated this by leading a group of government officials, accompanied by representatives of the press, to the top of the tower. Since the lifts were not yet in operation, the ascent was made by foot, and took over an hour, Eiffel frequently stopping to make explanations of various features. Most of the party chose to stop at the lower levels, but a few, including Nouguier, Compagnon, the President of the City Council and reporters from Le Figaro and Le Monde Illustré completed the climb. At 2.35 Eiffel hoisted a large tricolore, to the accompaniment of a 25-gun salute fired from the lower level. There was still work to be done, particularly on the lifts and the fitting out of the facilities for visitors, and the tower was not opened to the public until nine days after the opening of the Exposition on 6 May, and even then the lifts had not been completed.

The tower was an immediate success with the public, and lengthy queues formed to make the ascent. Tickets cost 2 francs for the first level, 3 for the second, and 5 for the top, with half-price admission on Sundays, and by the end of the exhibition there had been nearly two million visitors.

Eiffel had a permit for the tower to stand for 20 years; it was to be dismantled in 1909, when its ownership would revert to the City of Paris. The City had planned to tear it down (part of the original contest rules for designing a tower was that it could be easily demolished) but as the tower proved valuable for communication purposes, it was allowed to remain after the expiration of the permit. In the opening weeks of World War I, powerful radio transmitters were fitted to the tower in order to jam German communications. This seriously hindered their advance on Paris, and contributed to the Allied victory at the First Battle of the Marne.

Subsequent events

Panoramic view during ascension of the Eiffel Tower by the Lumière brothers, 1898

Panoramic view during ascension of the Eiffel Tower by the Lumière brothers, 1898

Franz Reichelt’s preparations and fall from the Eiffel Tower.

Franz Reichelt’s preparations and fall from the Eiffel Tower.

American soldiers watch the Eiffel Tower on 25 August 1944, during World War II.

Number of visitors per year between 1889 and 2004

Number of visitors per year between 1889 and 2004

- September 10, 1889

- Thomas Edison visited the tower. He signed the guestbook with the following message—

“To M Eiffel the Engineer the brave builder of so gigantic and original specimen of modern Engineering from one who has the greatest respect and admiration for all Engineers including the Great Engineer the Bon Dieu, Thomas Edison.”

- October 19, 1901

- Alberto Santos-Dumont in his Dirigible No.6 won a 10,000-franc prize offered by Henri Deutsch de la Meurthe for the first person to make a flight from St. Cloud to the Eiffel tower and back in less than half an hour.

- 1910

- Father Theodor Wulf measured radiant energy at the top and bottom of the tower. He found more at the top than expected, incidentally discovering what are today known as cosmic rays.

- February 4, 1912

- Austrian tailor Franz Reichelt died after jumping 60 metres from the first deck of the Eiffel tower with his homemade parachute.

- 1914

- A radio transmitter located in the tower jammed German radio communications during the lead-up to the First Battle of the Marne.

- 1925

- The con artist Victor Lustig “sold” the tower for scrap metal on two separate, but related occasions.

- February 1926

- Pilot Leon Collet killed after flying beneath the span of the tower, his airplane having become entangled in an aerial of the wireless station.

- May 21, 1927

- Charles Lindbergh piloted his “Spirit of Saint Louis” into Paris and circled the Eiffel tower before landing. “I first saw the lights of Paris a little before 10 p.m., or 5 p.m., New York time, and a few minutes later I was circling the Eiffel Tower at an altitude of about four thousand feet.”

- 1930

- The tower lost the title of the world’s tallest structure when the Chrysler Building was completed in New York City.

- 1925 to 1934

- Illuminated signs for Citroën adorned three of the tower’s four sides, making it the tallest advertising space in the world at the time.

- 1940–1944

- Upon the German occupation of Paris in 1940, the lift cables were cut by the French so that Adolf Hitler would have to climb the steps to the summit. The parts to repair them were allegedly impossible to obtain because of the war. In 1940 German soldiers had to climb to the top to hoist the swastika, but the flag was so large it blew away just a few hours later, and was replaced by a smaller one. When visiting Paris, Hitler chose to stay on the ground. It was said that Hitler conquered France, but did not conquer the Eiffel Tower. A Frenchman scaled the tower during the German occupation to hang the French flag. In August 1944, when the Allies were nearing Paris, Hitler ordered General Dietrich von Choltitz, the military governor of Paris, to demolish the tower along with the rest of the city. Von Choltitz disobeyed the order. Some say Hitler was later persuaded to keep the tower intact so it could later be used for communications. The lifts of the Tower were working normally within hours of the Liberation of Paris.

- January 3, 1956

- A fire damaged the top of the tower.

- 1957

- The present radio antenna was added to the top.

- 1980’s

- A restaurant and its supporting iron scaffolding midway up the tower was dismantled; it was purchased and reconstructed on St. Charles Avenue and Josephine Street in the Garden District of New Orleans, Louisiana, by entrepreneurs John Onorio and Daniel Bonnot, originally as the Tour Eiffel Restaurant, later as the Red Room and now as the Cricket Club (owned by the New Orleans Culinary Institute). The restaurant was re-assembled from 11,000 pieces that crossed the Atlantic in a 40-foot (12 m) cargo container.

- March 31, 1984

- Robert Moriarty flew a Beechcraft Bonanza through the arches of the tower.

- 1987

- A.J. Hackett made one of his first bungee jumps from the top of the Eiffel Tower, using a special cord he had helped develop. Hackett was arrested by the Paris police upon reaching the ground.

- October 27, 1991

- Thierry Devaux, along with mountain guide Hervé Calvayrac, performed a series of acrobatic figures of bungee jumping (not allowed) from the second floor of the Tower. Facing the Champ de Mars, Thierry Devaux was using an electric winch between each figure to go back up. When firemen arrived, he stopped after the sixth bungee jump.

- New Year’s Eve 1999

- The Eiffel Tower played host to Paris’s Millennium Celebration. On this occasion, flashing lights and four high-power searchlights were installed on the tower, and fireworks were set off all over it. An exhibition above a cafeteria on the first floor commemorates this event. Since then, the light show has become a nightly event. The searchlights on top of the tower make it a beacon in Paris’s night sky, and the 20,000 flash bulbs give the tower a sparkly appearance every hour on the hour.

- November 28, 2002

- The tower received its 200,000,000th guest.

- 2004

- The Eiffel Tower began hosting an ice skating rink on the first floor each winter.