Synagogue

Synagogue 1897 · Olomouc · History · Moravia Region · CZ · בית הכנסת

In times,when Olomouc started to sprawl over the boundaries of ancient walls,the new establishments reveled in the most variety of facades.It is this reason, that we see today all kinds of buildings the builders graced with variety of architecture elements from roman to the new-baroque styles or even their mixture. One such example was the building of the synagogue that was built in the oriental-Moorish style on the former Maria Theresa square.This building,designed by the Viennese architect Jakob Gartner,featured huge dome under which was the vast area of 450 spaces for men

and 300 separated spaces for women.The dome was constructed from iron structure resting on four footstalls covered with marble panels.The main façade was also covered with stone panels,windows and doorjambs carved form an artificial stone and main gates forged from iron.The building construction took less than two years;it started during summer 1895 and already on the11th April 1897 was put in operation.At that time, nobody anticipated that this building,in the next quarter of the century,would become a target of racial hatred and that its demise would signal the start of tragic fate of the Jewish population in Olomouc.The first Jewish settlements in Olomouc are

dated to 1848.The building was partly burned by local fascists during March 1939 and eventually completely destroyed the same year by German fascists.

A synagogue, also spelled synagog (from Greek συναγωγή transliterated synagogē, meaning “assembly”; בית כנסת beth knesset, meaning “house of assembly”; בית תפילהbeth t’fila, meaning “house of prayer”; שול shul; אסנוגה esnoga; קהל kahal) is a Jewish house of prayer. When broken down, the word could also mean “learning together” (from the Greek συν syn, “together”, and αγωγή agogé, “learning” or “training”).

A synagogue, also spelled synagog (from Greek συναγωγή transliterated synagogē, meaning “assembly”; בית כנסת beth knesset, meaning “house of assembly”; בית תפילהbeth t’fila, meaning “house of prayer”; שול shul; אסנוגה esnoga; קהל kahal) is a Jewish house of prayer. When broken down, the word could also mean “learning together” (from the Greek συν syn, “together”, and αγωγή agogé, “learning” or “training”).

Synagogues have a large hall for prayer (the main sanctuary), and may also have smaller rooms for study and sometimes a social hall and offices. Some have a separate room for Torah study, called the beth midrash (Sefaradi) “beis midrash (Ashkenazi)—בית מדרש(“House of Study”).

Synagogues are consecrated spaces that can be used only for the purpose of prayer; however a synagogue is not necessary for worship. Communal Jewish worship can be carried out wherever ten Jews (a minyan) assemble. Worship can also be carried out alone or with fewer than ten people assembled together. However there are certain prayers that are communal prayers and therefore can be recited only by a minyan. The synagogue does not replace the long-since destroyed Temple in Jerusalem.

Israelis use the Hebrew term beyt knesset (assembly house). Jews of Ashkenazi descent have traditionally used the Yiddish term “shul” (cognate with the German Schule, school) in everyday speech. Spanish and Portuguese Jews call the synagogue an esnoga. Persian Jews and Karaite Jews use the term Kenesa, which is derived from Aramaic, and some Arabic-speaking Jews use knis. Some Reform and Conservative Jews use the word “temple”. The Greek word “Synagogue” is a good all-around term, used in English (and German and French), to cover the preceding possibilities.

Origins

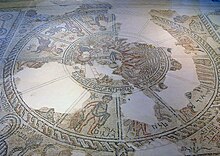

Mosaic in the Tzippori Synagogue

Ruins of the ancient synagogue of Kfar Bar’am

Although synagogues existed a long time before the destruction of the 2nd Temple in 70 CE, communal worship in the time while the Temple still stood centered around the korbanot(“sacrificial offerings”) brought by the kohanim (“priests”) in the Holy Temple. The all-day Yom Kippur service, in fact, was an event in which the congregation both observed the movements of the kohen gadol (“the high priest”) as he offered the day’s sacrifices and prayed for his success.

During the Babylonian captivity (586–537 BCE) the Men of the Great Assembly formalized and standardized the language of the Jewish prayers. Prior to that people prayed as they saw fit, with each individual praying in his or her own way, and there were no standard prayers that were recited. Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai, one of the leaders at the end of the Second Temple era, promulgated the idea of creating individual houses of worship in whatever locale Jews found themselves. This contributed to the continuity of the Jewish people by maintaining a unique identity and a portable way of worship despite the destruction of the Temple, according to many historians.

Synagogues in the sense of purpose-built spaces for worship, or rooms originally constructed for some other purpose but reserved for formal, communal prayer, however, existed long before the destruction of the Second Temple. The earliest archaeological evidence for the existence of very early synagogues comes from Egypt, where stone synagogue dedication inscriptions dating from the 3rd century BCE prove that synagogues existed by that date. A synagogue dating from between 75 and 50 BCE has been uncovered at a Hasmonean-era winter palace near Jericho. More than a dozen Second Temple era synagogues have been identified by archaeologists.

Any Jew or group of Jews can build a synagogue. Synagogues have been constructed by ancient Jewish kings, by wealthy patrons, as part of a wide range of human institutions including secular educational institutions, governments, and hotels, by the entire community of Jews living in a particular place, or by sub-groups of Jews arrayed according to occupation, ethnicity (i.e. the Sephardic, Polish or Persian Jews of a town), style of religious observance (i.e., a Reform or an Orthodox synagogue), or by the followers of a particular rabbi.

Architectural Design

Aerial view of the synagogue of the Kaifeng Jewish community in China.

There is no set blueprint for synagogues and the architectural shapes and interior designs of synagogues vary greatly. In fact, the influence from other local religious buildings can often be seen in synagogue arches, domes and towers.

Historically, synagogues were built in the prevailing architectural style of their time and place. Thus, the synagogue in Kaifeng, China looked very like Chinese temples of that region and era, with its outer wall and open garden in which several buildings were arranged. The styles of the earliest synagogues resembled the temples of other sects of the eastern Roman Empire. The surviving synagogues of medieval Spain are embellished with mudéjar plasterwork. The surviving medieval synagogues in Budapest and Prague are typical Gothic structures.

The emancipation of Jews in European countries not only enabled Jews to enter fields of enterprise from which they were formerly barred, but gave them the right to build synagogues without needing special permissions, synagogue architecture blossomed. Large Jewish communities wished to show not only their wealth but also their newly acquired status as citizens by constructing magnificent synagogues. These were built across Europe and in the United States in all of the historicist or revival styles then in fashion. Thus there were Neoclassical, Neo-Byzantine, Romanesque Revival, Moorish Revival, Gothic Revival, and Greek Revival. There are Egyptian Revival synagogues and even one Mayan Revival synagogue. In the 19th century and early 20th century heyday of historicist architecture, however, most historicist synagogues, even the most magnificent ones, did not attempt a pure style, or even any particular style, and are best described as eclectic.

In the post-war era, synagogue architecture abandoned historicist styles for modernism.

Interior Elements

Gothic interior of the 13th-century Old New Synagogue of Prague

Bimah at the Bialystoker Synagogue with Torah Ark in background.

Interior of the Portuguese Synagogue (Amsterdam) showing Tebah in the foreground, and Torah Ark in the background.

Bimah of the Łańcut Synagogue

All synagogues contain a bimah, a table from which the Torah is read, and a desk for the prayer leader.

The Torah ark, (Hebrew: Aron Kodesh—ארון קודש) (called the heikhal—היכל [temple] by Sephardim) is a cabinet in which the Torah scrolls are kept.

The ark in a synagogue is almost always positioned in such a way such that those who face it are facing towards Jerusalem. Thus, sanctuary seating plans in the Western world generally face east, while those east of Israel face west. Sanctuaries in Israel face towards Jerusalem. Occasionally synagogues face other directions for structural reasons; in such cases, some individuals might turn to face Jerusalem when standing for prayers, but the congregation as a whole does not.

The ark is reminiscent of the Ark of the Covenant which held the tablets inscribed with the Ten Commandments. This is the holiest spot in a synagogue, equivalent to the Holy of Holies. The ark is often closed with an ornate curtain, the parochet פרוכת, which hangs outside or inside the ark doors.

A large, raised, reader’s platform called the bimah (בימה) by Ashkenazim and tebah by Sephardim, where the Torah scroll is placed to be read is a feature of all synagogues. In Sephardi synagogues it is also used as the prayer leader’s reading desk.

Other traditional features include a continually lit lamp or lantern, usually electric in contemporary synagogues, called the ner tamid (נר תמיד), the “Eternal Light”, used as a reminder of the western lamp of the menorah of the Temple in Jerusalem, which remained miraculously lit perpetually. Many have an elaborate chair named for the prophet Elijahwhich is only sat upon during the ceremony of Brit milah. Many synagogues have a large seven-branched candelabrum commemorating the full Menorah. Most contemporary synagogues also feature a lectern for the rabbi.

A synagogue may be decorated with artwork, but in the Rabbinic and Orthodox tradition, three-dimensional sculptures and depictions of the human body are not allowed as these are considered akin to idolatry.

Until the 19th century, an Ashkenazi synagogue, all seats most often faced the ‘Torah Ark. In a Sephardi synagogue, seats were usually arranged around the perimeter of the sanctuary, but when the worshipers stood up to pray, everyone faced the Ark. In Ashkenazi synagogues The Torah was read on a reader’s table located in the center of the room, while the leader of the prayer service, the Hazzan, stood at his own lectern or table, facing the Ark. In Sephardic synagogues, the table for reading the Torah was commonly placed at the opposite side of the room from the Torah Ark, leaving the center of the floor empty for the use of a ceremonial procession carrying the Torah between the Ark and the reading table.