Spider-Man

Spider-Man S-3 E-2 “Make A Wish”

Spider-Man The Animated Series: Season 3 Episode 2 “Make A Wish.”

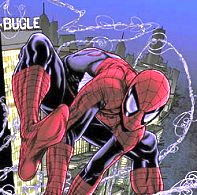

From The Amazing Spider-Man #547 (March 2008) Art by Steve McNiven and Dexter Vines

From The Amazing Spider-Man #547 (March 2008) Art by Steve McNiven and Dexter Vines

Spider-Man is a fictional character, a comic book superhero who appears in comic books published by Marvel Comics. In the comics Spider-Man is often referred to as “Spidey”, “web-slinger”, “wall-crawler”, or “web-head”. Created by writer-editor Stan Lee and writer-artist Steve Ditko, he first appeared in Amazing Fantasy #15 (August 1962). Lee and Ditko conceived the character as an orphan being raised by his Aunt May and Uncle Ben, and as a teenager, having to deal with the normal struggles of adolescence in addition to those of a costumed crimefighter. Spider-Man’s creators gave him super strength and agility, the ability to cling to most surfaces, shoot spider-webs using wrist-mounted devices of his own invention which he called “web-shooters”, and react to danger quickly with his “spider-sense”, enabling him to combat his foes.

When Spider-Man first appeared in the early 1960s, teenagers in superhero comic books were usually relegated to the role of sidekick to the protagonist. The Spider-Man series broke ground by featuring Peter Parker, a teenage high school student and person behind Spider-Man’s secret identity to whose “self-obsessions with rejection, inadequacy, and loneliness” young readers could relate. Unlike previous teen heroes such as Bucky and Robin, Spider-Man did not benefit from being the protégé of any adult superhero mentors like Captain America and Batman, and thus had to learn for himself that “with great power there must also come great responsibility”—a line included in a text box in the final panel of the first Spider-Man story, but later retroactively attributed to his guardian, the late Uncle Ben.

Marvel has featured Spider-Man in several comic book series, the first and longest-lasting of which is titled The Amazing Spider-Man. Over the years, the Peter Parker character has developed from shy, nerdy high school student to troubled but outgoing college student, to married high school teacher to, in the late 2000s, a single freelance photographer, his most typical adult role. In the 2010s he joins the Avengers and the Fantastic Four, Marvel’s flagship superhero teams. In December 2012 Peter Parker died while his mind was in the body of his enemy Doctor Octopus while Doctor Octopus lived on inside of Peter Parker’s body as The Superior Spider-Man.

Marvel has featured Spider-Man in several comic book series, the first and longest-lasting of which is titled The Amazing Spider-Man. Over the years, the Peter Parker character has developed from shy, nerdy high school student to troubled but outgoing college student, to married high school teacher to, in the late 2000s, a single freelance photographer, his most typical adult role. In the 2010s he joins the Avengers and the Fantastic Four, Marvel’s flagship superhero teams. In December 2012 Peter Parker died while his mind was in the body of his enemy Doctor Octopus while Doctor Octopus lived on inside of Peter Parker’s body as The Superior Spider-Man.

Spider-Man is one of the most popular and commercially successful superheroes. As Marvel’s flagship character and company mascot, he has appeared in many forms of media, including several animated and live-actiontelevision shows, syndicated newspaper comic strips, and a series of films starring Tobey Maguire as the “friendly neighborhood” hero in the first three movies. Andrew Garfield has taken over the role of Spider-Man in a reboot of the films. Reeve Carney stars as Spider-Man in the 2010 Broadway musical Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark. Spider-Man placed 3rd on IGN’s Top 100 Comic Book Heroes of All Time in 2011.

Publication history – Creation and development

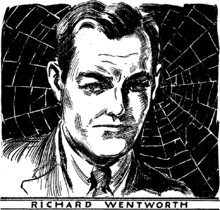

Richard Wentworth a.k.a. the Spider in the pulp magazine The Spider. Stan Lee stated that it was the name of this character that inspired him to create a character that would become Spider-Man.

Richard Wentworth a.k.a. the Spider in the pulp magazine The Spider. Stan Lee stated that it was the name of this character that inspired him to create a character that would become Spider-Man.

In 1962, with the success of the Fantastic Four, Marvel Comics editor and head writer Stan Lee was casting about for a new superhero idea. He said the idea for Spider-Man arose from a surge in teenage demand for comic books, and the desire to create a character with whom teens could identify. In his autobiography, Lee cites the non-superhuman pulp magazine crime fighter the Spider (see also The Spider’s Web and The Spider Returns) as a great influence, and in a multitude of print and video interviews, Lee stated he was further inspired by seeing a spider climb up a wall—adding in his autobiography that he has told that story so often he has become unsure of whether or not this is true. Looking back on the creation of Spider-Man, 1990s Marvel editor-in-chief Tom DeFalco stated he did not believe that Spider-Man would have been given a chance in today’s comics world, where new characters are vetted with test audiences and marketers. At that time, however, Lee had to get only the consent of Marvel publisher Martin Goodman for the character’s approval. In a 1986 interview, Lee described in detail his arguments to overcome Goodman’s objections. Goodman eventually agreed to let Lee try out Spider-Man in the upcoming final issue of the canceled science-fiction and supernatural anthology seriesAmazing Adult Fantasy, which was renamed Amazing Fantasy for that single issue, #15 (Aug. 1962).

Comics historian Greg Theakston says that Lee, after receiving Goodman’s approval for the name Spider-Man and the “ordinary teen” concept, approached artist Jack Kirby. Kirby told Lee about an unpublished character on which he collaborated with Joe Simon in the 1950s, in which an orphaned boy living with an old couple finds a magic ring that granted him superhuman powers. Lee and Kirby “immediately sat down for a story conference” and Lee afterward directed Kirby to flesh out the character and draw some pages. Steve Ditko would be the inker. When Kirby showed Lee the first six pages, Lee recalled, “I hated the way he was doing it! Not that he did it badly—it just wasn’t the character I wanted; it was too heroic.” Lee turned to Ditko, who developed a visual style Lee found satisfactory. Ditko recalled:

“One of the first things I did was to work up a costume. A vital, visual part of the character. I had to know how he looked … before I did any breakdowns. For example: A clinging power so he wouldn’t have hard shoes or boots, a hidden wrist-shooter versus a web gun and holster, etc. … I wasn’t sure Stan would like the idea of covering the character’s face but I did it because it hid an obviously boyish face. It would also add mystery to the character….”

Although the interior artwork was by Ditko alone, Lee rejected Ditko’s cover art and commissioned Kirby to pencil a cover that Ditko inked. As Lee explained in 2010, “I think I had Jack sketch out a cover for it because I always had a lot of confidence in Jack’s covers.”

Although the interior artwork was by Ditko alone, Lee rejected Ditko’s cover art and commissioned Kirby to pencil a cover that Ditko inked. As Lee explained in 2010, “I think I had Jack sketch out a cover for it because I always had a lot of confidence in Jack’s covers.”

In an early recollection of the character’s creation, Ditko described his and Lee’s contributions in a mail interview with Gary Martin published in Comic Fan #2 (Summer 1965): “Stan Lee thought the name up. I did costume, web gimmick on wrist & spider signal.” At the time, Ditko shared a Manhattan studio with noted fetish artist Eric Stanton, an art-school classmate who, in a 1988 interview with Theakston, recalled that although his contribution to Spider-Man was “almost nil”, he and Ditko had “worked on storyboards together and I added a few ideas. But the whole thing was created by Steve on his own… I think I added the business about the webs coming out of his hands.”

Kirby disputed Lee’s version of the story, and claimed Lee had minimal involvement in the character’s creation. According to Kirby, the idea for Spider-Man had originated with Kirby and Joe Simon, who in the 1950s had developed a character called the Silver Spider for the Crestwood Publications comic Black Magic, who was subsequently not used. Simon, in his 1990 autobiography, disputed Kirby’s account, asserting that Black Magic was not a factor, and that he (Simon) devised the name “Spider-Man” (later changed to “The Silver Spider”), while Kirby outlined the character’s story and powers. Simon later elaborated that his and Kirby’s character conception became the basis for Simon’s Archie Comics superhero the Fly. Artist Steve Ditko stated that Lee liked the name Hawkman from DC Comics, and that “Spider-Man” was an outgrowth of that interest.

Simon concurred that Kirby had shown the original Spider-Man version to Lee, who liked the idea and assigned Kirby to draw sample pages of the new character but disliked the results—in Simon’s description, “Captain America with cobwebs.” Writer Mark Evanier notes that Lee’s reasoning that Kirby’s character was too heroic seems unlikely—Kirby still drew the covers forAmazing Fantasy #15 and the first issue of The Amazing Spider-Man. Evanier also disputes Kirby’s given reason that he was “too busy” to also draw Spider-Man in addition to his other duties since Kirby was, said Evanier, “always busy.” Neither Lee’s nor Kirby’s explanation explains why key story elements like the magic ring were dropped; Evanier states that the most plausible explanation for the sudden change was that Goodman, or one of his assistants, decided that Spider-Man as drawn and envisioned by Kirby was too similar to the Fly.

Author and Ditko scholar Blake Bell writes that it was Ditko who noted the similarities to the Fly. Ditko recalled that, “Stan called Jack about the Fly”, adding that “[d]ays later, Stan told me I would be penciling the story panel breakdowns from Stan’s synopsis”. It was at this point that the nature of the strip changed. “Out went the magic ring, adult Spider-Man and whatever legend ideas that Spider-Man story would have contained”. Lee gave Ditko the premise of a teenager bitten by a spider and developing powers, a premise Ditko would expand upon to the point he became what Bell describes as “the first work for hire artist of his generation to create and control the narrative arc of his series”. On the issue of the initial creation, Ditko states, “I still don’t know whose idea was Spider-Man.” Kirby noted in a 1971 interview that it was Ditko who “got Spider-Man to roll, and the thing caught on because of what he did.” Lee, while claiming credit for the initial idea, has acknowledged Ditko’s role, stating, “If Steve wants to be called co-creator, I think he deserves [it].” Writer Al Nickerson believes “that Stan Lee and Steve Ditko created the Spider-Man that we are familiar with today [but that] ultimately, Spider-Man came into existence, and prospered, through the efforts of not just one or two, but many, comic book creators.”

In 2008, an anonymous donor bequeathed the Library of Congress the original 24 pages of Ditko art of Amazing Fantasy #15, including Spider-Man’s debut and the stories “The Bell-Ringer”, “Man in the Mummy Case”, and “There Are Martians Among Us.”

Commercial success

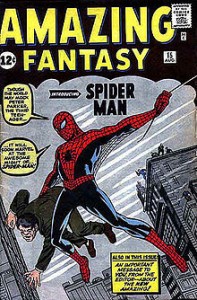

Amazing Fantasy #15 (Aug. 1962). The issue that first introduced the fictional character. It was a gateway to the commercial success to the superhero and inspired the launch of The Amazing Spider-Man comics. Cover art by Jack Kirby (penciller) and Steve Ditko (inker).

Amazing Fantasy #15 (Aug. 1962). The issue that first introduced the fictional character. It was a gateway to the commercial success to the superhero and inspired the launch of The Amazing Spider-Man comics. Cover art by Jack Kirby (penciller) and Steve Ditko (inker).

The character first appeared in Amazing Fantasy #15 which was published in June 1962 (though with a cover date of August). A few months after Spider-Man’s introduction in Amazing Fantasy #15 (Aug. 1962), publisher Martin Goodman reviewed the sales figures for that issue and was shocked to find it to have been one of the nascent Marvel’s highest-selling comics. A solo ongoing series followed, beginning with The Amazing Spider-Man #1 (March 1963). The title eventually became Marvel’s top-selling series with the character swiftly becoming a cultural icon; a 1965 Esquire poll of college campuses found that college students ranked Spider-Man and fellow Marvel hero the Hulk alongside Bob Dylan and Che Guevara as their favorite revolutionary icons. One interviewee selected Spider-Man because he was “beset by woes, money problems, and the question of existence. In short, he is one of us.” Following Ditko’s departure after issue #38 (July 1966), John Romita, Sr. replaced him as penciler and would draw the series for the next several years. In 1968, Romita would also draw the character’s extra-length stories in the comics magazine The Spectacular Spider-Man, a proto-graphic novel designed to appeal to older readers. It only lasted for two issues, but it represented the first Spider-Man spin-off publication, aside from the original series’ summer annuals that began in 1964.

An early 1970s Spider-Man story led to the revision of the Comics Code. Previously, the Code forbade the depiction of the use of illegal drugs, even negatively. However, in 1970, the Nixon administration’s Department of Health, Education, and Welfare asked Stan Lee to publish an anti-drug message in one of Marvel’s top-selling titles. Lee chose the top-selling The Amazing Spider-Man; issues #96–98 (May–July 1971) feature a story arc depicting the negative effects of drug use. In the story, Peter Parker’s friendHarry Osborn becomes addicted to pills. When Spider-Man fights the Green Goblin (Norman Osborn, Harry’s father), Spider-Man defeats the Green Goblin, by revealing Harry’s drug addiction. While the story had a clear anti-drug message, the Comics Code Authority refused to issue its seal of approval. Marvel nevertheless published the three issues without the Comics Code Authority’s approval or seal. The issues sold so well that the industry’s self-censorship was undercut and the Code was subsequently revised.

In 1972, a second monthly ongoing series starring Spider-Man began: Marvel Team-Up, in which Spider-Man was paired with other superheroes and villains. From that point on there have generally been at least two ongoing Spider-Man series at any time. In 1976, his second solo series, Peter Parker, the Spectacular Spider-Man began running parallel to the main series. A third series featuring Spider-Man, Web of Spider-Man, launched in 1985 to replace Marvel Team-Up. The launch of a fourth monthly title in 1990, the “adjectiveless” Spider-Man (with the storyline “Torment“), written and drawn by popular artist Todd McFarlane, debuted with several different covers, all with the same interior content. The various versions combined sold over 3 million copies, an industry record at the time. Several limited series, one-shots, and loosely related comics have also been published, and Spider-Man makes frequent cameos and guest appearances in other comic series. In 1996 The Sensational Spider-Man was created to replace Web of Spider-Man.

In 1972, a second monthly ongoing series starring Spider-Man began: Marvel Team-Up, in which Spider-Man was paired with other superheroes and villains. From that point on there have generally been at least two ongoing Spider-Man series at any time. In 1976, his second solo series, Peter Parker, the Spectacular Spider-Man began running parallel to the main series. A third series featuring Spider-Man, Web of Spider-Man, launched in 1985 to replace Marvel Team-Up. The launch of a fourth monthly title in 1990, the “adjectiveless” Spider-Man (with the storyline “Torment“), written and drawn by popular artist Todd McFarlane, debuted with several different covers, all with the same interior content. The various versions combined sold over 3 million copies, an industry record at the time. Several limited series, one-shots, and loosely related comics have also been published, and Spider-Man makes frequent cameos and guest appearances in other comic series. In 1996 The Sensational Spider-Man was created to replace Web of Spider-Man.

In 1998 writer-artist John Byrne revamped the origin of Spider-Man in the 13-issue limited series Spider-Man: Chapter One (Dec. 1998 – Oct. 1999), similar to Byrne’s adding details and some revisions to Superman’s origin in DC Comics‘ The Man of Steel. At the same time the original The Amazing Spider-Man was ended with issue #441 (Nov. 1998), and The Amazing Spider-Manwas restarted with vol. 2, #1 (Jan. 1999). In 2003 Marvel reintroduced the original numbering for The Amazing Spider-Man and what would have been vol. 2, #59 became issue #500 (Dec. 2003).

When primary series The Amazing Spider-Man reached issue #545 (Dec. 2007), Marvel dropped its spin-off ongoing series and instead began publishing The Amazing Spider-Man three times monthly, beginning with #546-549 (all January 2008). The three times monthly scheduling of The Amazing Spider-Man lasted until November 2010 when the comic book was increased from 22 pages to 30 pages each issue and published only twice a month, beginning with #648-649 (all November 2010). The following year (November 2011) Marvel started publishing Avenging Spider-Man as the first spin-off ongoing series in addition to the still twice monthly The Amazing Spider-Man since the previous ones were cancelled at the end of 2007. The Amazingseries ends with issue #700, with the villain Doctor Octopus, having taken over Spider-Man’s body, to be featured in a new series titled The Superior Spider-Man.

Fictional character biography

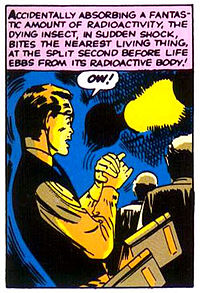

The spider bite that gave Peter Parker his powers. Amazing Fantasy#15, art by Steve Ditko.

The spider bite that gave Peter Parker his powers. Amazing Fantasy#15, art by Steve Ditko.

In Forest Hills, Queens, New York City, high school student Peter Parker is a science-whiz orphan living with his Uncle Ben and Aunt May. As depicted in Amazing Fantasy #15 (Aug. 1962), he is bitten by a radioactive spider (erroneously classified as an insect in the panel) at a science exhibit and “acquires the agility and proportionate strength of an arachnid.” Along with super strength, he gains the ability to adhere to walls and ceilings. Through his native knack for science, he develops a gadget that lets him fire adhesive webbing of his own design through small, wrist-mounted barrels. Initially seeking to capitalize on his new abilities, he dons a costume and, as “Spider-Man”, becomes a novelty television star. However, “He blithely ignores the chance to stop a fleeing thief, [and] his indifference ironically catches up with him when the same criminal later robs and kills his Uncle Ben.” Spider-Man tracks and subdues the killer and learns, in the story’s next-to-last caption, “With great power there must also come—great responsibility!”

Despite his superpowers, Parker struggles to help his widowed aunt pay rent, is taunted by his peers—particularly football star Flash Thompson—and, as Spider-Man, engenders the editorial wrath of newspaper publisher J. Jonah Jameson. As he battles his enemies for the first time, Parker finds juggling his personal life and costumed adventures difficult. In time, Peter graduates from high school, and enrolls at Empire State University (a fictional institution evoking the real-life Columbia University and New York University), where he meets roommate and best friend Harry Osborn, and girlfriend Gwen Stacy, and Aunt May introduces him to Mary Jane Watson. As Peter deals with Harry’s drug problems, and Harry’s father is revealed to be Spider-Man’s nemesis the Green Goblin, Peter even attempts to give up his costumed identity for a while. Gwen Stacy’s father, New York City Police detective captain George Stacy is accidentally killed during a battle between Spider-Man and Doctor Octopus (#90, Nov. 1970). In the course of his adventures Spider-Man has made a wide variety of friends and contacts within the superhero community, who often come to his aid when he faces problems that he cannot solve on his own.

In issue #121 (June 1973), the Green Goblin throws Gwen Stacy from a tower of either the Brooklyn Bridge (as depicted in the art) or the George Washington Bridge (as given in the text). She dies during Spider-Man’s rescue attempt; a note on the letters page of issue #125 states: “It saddens us to say that the whiplash effect she underwent when Spidey’s webbing stopped her so suddenly was, in fact, what killed her.” The following issue, the Goblin appears to accidentally kill himself in the ensuing battle with Spider-Man.

In issue #121 (June 1973), the Green Goblin throws Gwen Stacy from a tower of either the Brooklyn Bridge (as depicted in the art) or the George Washington Bridge (as given in the text). She dies during Spider-Man’s rescue attempt; a note on the letters page of issue #125 states: “It saddens us to say that the whiplash effect she underwent when Spidey’s webbing stopped her so suddenly was, in fact, what killed her.” The following issue, the Goblin appears to accidentally kill himself in the ensuing battle with Spider-Man.

Working through his grief, Parker eventually develops tentative feelings toward Watson, and the two “become confidants rather than lovers.” Parker graduates from college in issue #185, and becomes involved with the shy Debra Whitman and the extroverted, flirtatious costumed thief Felicia Hardy, the Black Cat, whom he meets in issue #194 (July 1979).

From 1984 to 1988, Spider-Man wore a black costume with a white spider design on his chest. The new costume originated in the Secret Wars limited series, on an alien planet where Spider-Man participates in a battle between Earth’s major superheroes and villains. He continues wearing the costume when he returns from the Secret Wars, starting in The Amazing Spider-Man #252. Not unexpectedly, the change to a longstanding character’s iconic design met with controversy, “with many hardcore comics fans decrying it as tantamount to sacrilege. Spider-Man’s traditional red and blue costume was iconic, they argued, on par with those of his D.C. rivals Superman and Batman.” The creators then revealed the costume was an alien symbiote which Spider-Man is able to reject after a difficult struggle, though the symbiote returns several times as Venom for revenge.

Parker proposes to Watson in The Amazing Spider-Man #290 (July 1987), and she accepts two issues later, with the wedding taking place in The Amazing Spider-Man Annual #21 (1987)—promoted with a real-life mock wedding using actors (with model Tara Shannon as Watson) at Shea Stadium, with Stan Lee officiating, on June 5, 1987. However, David Michelinie, who scripted based on a plot by editor-in-chief Jim Shooter, said in 2007, “I didn’t think they actually should [have gotten] married. … I had actually planned another version, one that wasn’t used.” In a controversial storyline, Peter becomes convinced that Ben Reilly, the Scarlet Spider (a clone of Peter created by his college professor Miles Warren) is the real Peter Parker, and that he, Peter, is the clone. Peter gives up the Spider-Man identity to Reilly for a time, until Reilly is killed by the returning Green Goblin and revealed to be the clone after all. In stories published in 2005 and 2006 (such as “The Other“), he develops additional spider-like abilities including biological web-shooters, toxic stingers that extend from his forearms, the ability to stick individuals to his back, enhanced Spider-sense and night vision, and increased strength and speed. Peter later becomes a member of the New Avengers, and reveals his civilian identity to the world, furthering his already numerous problems. His marriage to Mary Jane and public unmasking are later erased in the controversial storyline “One More Day“, in a Faustian bargain with the demon Mephisto, resulting in several adjustments to the timeline, such as the resurrection of Harry Osborn, the erasure of Parker’s marriage, and the return of his traditional tools and powers.

Parker proposes to Watson in The Amazing Spider-Man #290 (July 1987), and she accepts two issues later, with the wedding taking place in The Amazing Spider-Man Annual #21 (1987)—promoted with a real-life mock wedding using actors (with model Tara Shannon as Watson) at Shea Stadium, with Stan Lee officiating, on June 5, 1987. However, David Michelinie, who scripted based on a plot by editor-in-chief Jim Shooter, said in 2007, “I didn’t think they actually should [have gotten] married. … I had actually planned another version, one that wasn’t used.” In a controversial storyline, Peter becomes convinced that Ben Reilly, the Scarlet Spider (a clone of Peter created by his college professor Miles Warren) is the real Peter Parker, and that he, Peter, is the clone. Peter gives up the Spider-Man identity to Reilly for a time, until Reilly is killed by the returning Green Goblin and revealed to be the clone after all. In stories published in 2005 and 2006 (such as “The Other“), he develops additional spider-like abilities including biological web-shooters, toxic stingers that extend from his forearms, the ability to stick individuals to his back, enhanced Spider-sense and night vision, and increased strength and speed. Peter later becomes a member of the New Avengers, and reveals his civilian identity to the world, furthering his already numerous problems. His marriage to Mary Jane and public unmasking are later erased in the controversial storyline “One More Day“, in a Faustian bargain with the demon Mephisto, resulting in several adjustments to the timeline, such as the resurrection of Harry Osborn, the erasure of Parker’s marriage, and the return of his traditional tools and powers.

That storyline came at the behest of editor-in-chief Joe Quesada, who said, “Peter being single is an intrinsic part of the very foundation of the world of Spider-Man.” It caused unusual public friction between Quesada and writer J. Michael Straczynski, who “told Joe that I was going to take my name off the last two issues of the [story] arc” but was talked out of doing so. At issue with Straczynski’s climax to the arc, Quesada said, was

That storyline came at the behest of editor-in-chief Joe Quesada, who said, “Peter being single is an intrinsic part of the very foundation of the world of Spider-Man.” It caused unusual public friction between Quesada and writer J. Michael Straczynski, who “told Joe that I was going to take my name off the last two issues of the [story] arc” but was talked out of doing so. At issue with Straczynski’s climax to the arc, Quesada said, was

“…that we didn’t receive the story and methodology to the resolution that we were all expecting. What made that very problematic is that we had four writers and artists well underway on [the sequel arc] “Brand New Day” that were expecting and needed “One More Day” to end in the way that we had all agreed it would. … The fact that we had to ask for the story to move back to its original intent understandably made Joe upset and caused some major delays and page increases in the series. Also, the science that Joe was going to apply to the retcon of the marriage would have made over 30 years of Spider-Man books worthless, because they never would have had happened. …[I]t would have reset way too many things outside of the Spider-Man titles. We just couldn’t go there….”

Following the “reboot”, Parker’s identity was no longer known to the general public; however, he revealed it to his teammates in the New Avengers and his friends in the Fantastic Four, and others have deduced it. Parker’s Aunt May married J. Jonah Jameson’s father, Jay Jameson. Jonah himself has been elected Mayor of New York City, and Parker became an employee of the think-tank Horizon Labs.

In issue #700, after the dying supervillain Doctor Octopus has swapped bodies with him, Parker dies. However, the ending of The Superior Spider-Man #1 shows that Parker still exists within Doctor Octopus’s mind and vows to find a way to return to his body, but Doctor Octopus learns of his presence in his mind and removes his presence to be completely free to control Parker’s former body.