Paul Robeson

Paul Robeson and Hattie McDaniel sing a duet

Paul Robeson and Hattie McDaniel sings “Ah Still Suits Me” from the film, Show Boat (1936).

Paul Leroy Robeson (

Paul Leroy Robeson (![]() /ˈroʊbsən/ rohb-sən April 9, 1898 – January 23, 1976) was an American singer and actor who was a political activist for the Civil Rights Movement. His advocacy of anti-imperialism, affiliation with Communism, and criticism of the US brought retribution from the government and public condemnation. He was blacklisted, and to his financial and social detriment, he refused to rescind his stand on his beliefs and remained opposed to the direction of US policies.

/ˈroʊbsən/ rohb-sən April 9, 1898 – January 23, 1976) was an American singer and actor who was a political activist for the Civil Rights Movement. His advocacy of anti-imperialism, affiliation with Communism, and criticism of the US brought retribution from the government and public condemnation. He was blacklisted, and to his financial and social detriment, he refused to rescind his stand on his beliefs and remained opposed to the direction of US policies.

Robeson won a scholarship to Rutgers University, where he was a football All-American and class valedictorian. He graduated from Columbia Law School while playing in the National Football League (NFL) and singing and acting in off-campus productions. After theatrical performances in The Emperor Jones and All God’s Chillun Got Wings he became an integral part of the Harlem Renaissance.

Robeson’s renditions of spirituals, broadcast in, and imported to, Great Britain, became part of popular music in Great Britain in the 20th century. His portrayal of Shakespeare‘s Othello was the first of someone of African descent to take the role in Great Britain, in an otherwise all-white cast, since Ira Aldridge‘s 19th century portrayal.

His father’s background as a former slave, and his personal awareness of social injustices transformed Robeson into a political activist. He became a supporter of the Republican forces of the Spanish Civil War and then became active in the Council on African Affairs (CAA). During World War II, he played Othello in America while supporting the country’s war effort. After the war ended, the CAA was placed on the Attorney General’s List of Subversive Organizations (AGLOSO) and he was scrutinized during the age of McCarthyism.

Due to his decision to not recant his beliefs, he was denied an international visa, and his income plummeted. He settled in Harlem and published a periodical critical of US policies. His right to travel was restored by Kent v. Dulles, but his health soon broke down. He retired privately and remained recalcitrant to the policies of the US government until his death.

Early life – Childhood (1898–1915)

Paul Robeson was born in Princeton in 1898, to Reverend William Drew Robeson and Maria Louisa Bustill. His mother was from a prominent Quaker family of mixed ancestry: African, Anglo-American, and Lenape. His father, William, escaped from a plantation in his teens and eventually became the minister of Princeton’s Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church in 1881. Robeson had three brothers, William Drew, Jr. (born 1881), Reeve (born c. 1887), and Ben (born c. 1893), and one sister, Marian (born c. 1895).

In 1900, a disagreement between William and white, financial supporters of Witherspoon arose with apparent racial undertones, which were prevalent in Princeton. William, who had the support of his entirely black congregation, resigned in 1901. The loss of his position forced him to work menial jobs. Three years later when Robeson was six, his mother, who was nearly blind, tragically died in a house fire. Eventually, William became financially incapable of providing a house for himself and his children still living at home, Ben and Robeson, so they moved into the attic of a store in Westfield, New Jersey.

William found a stable parsonage at the St. Thomas A. M. E. Zion in 1910, where Robeson would fill in for his father during sermons when he was called away. In 1912, Robeson attended Somerville High School, where he performed in Julius Caesar, Othello, sang in the chorus, and excelled in football, basketball, baseball and track. His athletic dominance elicited racial taunts which he ignored. Prior to his graduation, he won a statewide academic contest for a scholarship to Rutgers. He took a summer job as a waiter in Narragansett Pier, Rhode Island, where he befriended Fritz Pollard.

Rutgers University (1915–1919)

Robeson (far left) was Rutgers Class of 1919 and one of four students selected into Cap and Skull

In late 1915, Robeson became the third African-American student ever enrolled at Rutgers, and the only one at the time. He tried out for the Rutgers Scarlet Knights football team, and his resolve to make the squad was tested as his teammates engaged in unwarranted and excessive play, arguably precipitated by racism. The coach, Foster Sanford, recognized his perseverance and allowed him onto the team.

He joined the debate team and sang off-campus for spending money, and on-campus with the Glee Club informally, as membership required attending all-white mixers. He also joined the other collegiate athletic teams. As a sophomore, amidst Rutgers’ sesquicentennial celebration, he was insultingly benched when a Southern team refused to take the field because the Scarlet Knights had fielded a Negro, Robeson.

After a standout junior year of football, he was recognized in The Crisis for his athletic, academic, and singing talents. At what should have been a high point of his life, his father fell grievously ill. Robeson took sole responsibility to care for him, shuttling between Rutgers and Somerville. His father soon died, and at Rutgers, Robeson expounded on the incongruity of African-Americans fighting to protect America (in World War I) and not being afforded the same opportunities as whites.

He finished university with four annual oratorical triumphs and varsity letters in multiple sports. His play at end won him first-team All-American selection, in both his junior and senior years. Walter Camp considered him the greatest end ever. Academically, he was accepted into Phi Beta Kappa and Cap and Skull. His classmates recognized him by electing him class valedictorian. The Daily Targum published a poem featuring his achievements. In his valedictorian speech, he exhorted his classmates to work for equality for all Americans.

Columbia Law School (1919–1923)

Robeson entered New York University School of Law in the fall of 1919. To support himself, he became an assistant football coach at Lincoln, where he joined the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity. Harlem had recently changed its predominantly Jewish American population to an almost entirely African-American one, and Robeson was drawn to it. He transferred to Columbia Law School in February 1920 and moved to Harlem.

Already well-known in the black community for his singing, he was selected to perform at the dedication of the Harlem YWCA. He began dating Eslanda “Essie” Goode, a histological chemist at NewYork–Presbyterian Hospital. After Essie’s coaxing, he gave his theatrical debut as Simon in Ridgely Torrence‘s Simon of Cyrene. After a year of courtship, they were married in August 1921.

He was recruited by Pollard to play for the NFL’s Akron Pros, while he continued his law studies. In the spring, he postponed school to portray Jim in Mary Hoyt Wiborg‘s Taboo. He then sang in a chorus in an Off-Broadway production of Shuffle Along before he joinedTaboo in Britain. The play was adapted by director Mrs. Patrick Campbell to highlight his singing. After the play ended, he befriended Lawrence Brown, a classically trained musician, before returning to Columbia while playing for the NFL’s Milwaukee Badgers. He ended his football career after 1922, and months later, he graduated from law school.

Theatrical ascension and ideological transformation (1923–1939) – Harlem Renaissance (1923–1927)

Robeson briefly worked as a lawyer, but he renounced a career in law due to extant racism. Essie, the chief histological chemist at New York-Presbyterian Hospital, financially supported them and they frequented the social functions at the future Schomburg Center. In December, he landed the lead role of Jim in Eugene O’Neill‘s All God’s Chillun Got Wings, which culminated with Jim metaphorically consummating his marriage with his white wife by symbolically emasculating himself. Chillun’s opening was postponed while a nationwide debate occurred over its plot.

Chillun’s delay led to a revival of The Emperor Jones with Robeson as Brutus, a role pioneered by Charles Sidney Gilpin. The role terrified and galvanized Robeson as it was practically a 90-minute soliloquy. Reviews declared him an unequivocal success. Though arguably clouded by its controversial subject, his Jim in Chillun was less well received. He deflected criticism of its plot by writing that fate had drawn him to the “untrodden path” of drama and the true measure of a culture is in its artistic contributions, and the only true American culture was African-American.

The popular success of his acting placed him in elite social circles and his ascension to fame, which was forcefully aided by Essie, had occurred at a startling pace. Essie’s naked ambition for Robeson was a startling dichotomy to his insouciance. She quit her job, became his agent, and negotiated his first movie role in a silent race film directed by Oscar Micheaux, Body and Soul. To support a charity for single mothers, he headlined a concert singing spirituals. He performed his repertoire of spirituals on the radio.

Brown, who had become renown while touring with gospel singer Roland Hayes, stumbled on Robeson in Harlem. The two ad-libbed a set of spirituals, with Robeson as lead and Brown as accompanist. This so enthralled them that they booked Provincetown Playhouse for a concert. The pair’s rendition of African-American folk songs and spirituals was captivating, and Victor Records signed Robeson to a contract.

The Robesons went to London for a revival of Jones, before spending the rest of the fall on holiday on the French Riviera socializing with Gertrude Stein and Claude McKay. Robeson and Brown performed a series of concert tours in America from January 1926 until May 1927. During a hiatus in New York, Robeson learned that Essie was several months pregnant. Paul Jr. was born while Robeson and Brown toured Europe. Essie experienced complications from the birth, and by mid-December, her health had deteriorated dramatically. Ignoring her objections, her mother wired Robeson and he immediately returned to her bedside. Essie completely recovered after a few months.

Show Boat, Othello, and marriage difficulties (1928–1932)

Robeson played the stevedore “Joe” in the London production of the American musical Show Boat, at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. His rendition of “Ol’ Man River” became the benchmark for all future performers of the song. Some black critics were not pleased with the play due to its usage of the word nigger. It was, nonetheless, immensely popular with white audiences, and it gained the attendance of Queen Mary. He was summoned for a Royal Command Performance at Buckingham Palace in honor of the King of Spain, Alfonso XIII. He was befriended by MPs from the House of Commons. Show Boat continued for 350 performances and as of 2001, it remained the Royal’s most profitable venture. Feeling comfortable in London, the Robesons’ bought a home, at a later recipient of the English Heritage Blue Plaque, in Hampstead. He reflected on his life in his diary and wrote that it was all part of a “‘higher plan'” and “God watches over me and guides me. He’s with me and lets me fight my own battles and hopes I’ll win.” However, an incident at the Savoy Grill, wherein he was refused to be seated, sparked him to issue a press release portraying the insult which subsequently became a matter of public debate.

Essie had learned early in their marriage that Robeson had been involved in extramarital affairs, but she tolerated them. However, when she discovered that he was having an affair with a Ms. Jackson, she unfavorably altered the characterization of him in his biography, and defamed him by describing him with “negative racial stereotypes”, which he found appalling. Despite her uncovering of this tryst, there was no public evidence that their relationship had soured. In early 1930, they both appeared in the experimental classic Borderline, and then returned to the West End for his starring role in Shakespeare’s Othello, opposite Peggy Ashcroft as Desdemona.

Robeson became the first black actor cast as Othello in Britain since Ira Aldridge. The production received mixed reviews which pointed out Robeson’s “highly civilized quality [but lacking the] grand style.” Drawn into an interview, he stated that the best way to diminish the oppression African-Americans faced was for his artistic work to be an example of what “men of my colour” could accomplish rather than to “be a propagandist and make speeches and write articles about what they call the Colour Question.”

After Essie’s discovery of Robeson’s affair with Ashcroft, she decided to seek a divorce and they split up. While Jackson and he broached marriage, he returned to Broadway as Joe in the 1932 revival of Show Boat, to critical and popular acclaim. Subsequently, he received, with immense pride, an honorary master’s degree from Rutgers. Thereabout, his former football coach, Foster Sanford, advised him that divorcing Essie and marrying Jackson would do irreparable damage to his reputation. Jackson’s and Robeson’s relationship ended in 1932, following which Robeson and Essie reconciled, although their relation was permanently scarred.

Ideological awakening (1933–1937)

Robeson returned to the theatre as Joe in “Chillun” in 1933 because he found the character stimulating. He received no financial compensation for “Chillun”, but he was a pleasure to work with. The play ran for several weeks and was panned by critics, except for his acting. He then returned to the US for a lucrative portrayal of Brutus in the film The Emperor Jones. “Jones” became the first feature sound film starring an African American, a feat not repeated for more than two decades in the U.S. His acting was well-received, but offensive language in the script caused controversy. On the film set he rejected any slight to his dignity, notwithstanding the widespread Jim Crow attitudes. Although, the winter of 1932–1933 was the worst economic period in American history, he was unappreciative of the unfurling disaster.

Post-production, Robeson returned home to England and publicly criticized African Americans’ rejection of their own culture. His comments brought rebuke from the New York Amsterdam News, which retorted that his elitism had made a “‘jolly well [ass of himself].'” He declared that he would reject any offers to perform European opera because the music had no connection to his heritage. He enrolled in the School of Oriental and African Studies to study Swahili and Bantu, among other languages. His “sudden interest” in African history and its impact on culture coincided with his essay “I Want to be African”, wherein he wrote of his desire to embrace his ancestry. He undertook Bosambo in the movie Sanders of the River, which he felt would render a realistic view of colonial African culture. His friends in the anti-imperialism movement and association with British socialists led him to visit the USSR. Robeson, Essie, and Marie Seton embarked to the USSR on an invitation from Sergei Eisenstein in December 1934. During their trip, a stopover in Berlin enlightened Robeson to the racism in Nazi Germany, and on his arrival in the USSR, he promulgated the irrelevance of his race which he felt in Moscow.

When Sanders of the Rivers was released in 1935, it made him an international movie star. However, his stereotypical portrayal of a colonial African was seen as embarrassing to his stature as an artist and damaging to his reputation. The Commissioner of Nigeria to London protested the film as slanderous to his country, and Robeson henceforth became more politically conscious of his roles. In early 1936 he considered himself primarily apolitical, however he decided to send his son to school in the Soviet Union in order to shield him from racist attitudes. He then played the role of Toussaint Louverture in the eponymous play by C. L. R. James at the Westminster Theatre and appeared in the films Song of Freedom, Show Boat, Big Fella, My Song Goes Forth (a.k.a. Africa Sings), and King Solomon’s Mines. He was internationally recognized as the 10th-most popular star in British cinema.

Spanish Civil War (1937–1939)

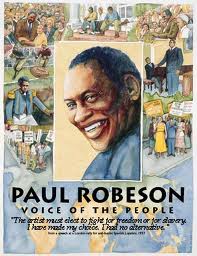

Robeson would later write the struggle against fascism during the Spanish Civil War was a turning point in his life, transforming him into a political activist and artist. In 1937, he used his concert performances to advocate the Republican cause and the war’s refugees. He permanently modified his renditions of Ol’ Man River from a show tune into a battle hymn of unwavering defiance. His business agent expressed concern about his political involvement, but Robeson overruled him and decided that contemporary events trumped commercialism In Wales, he commemorated the Welsh killed while fighting for the Republicans, where he recorded a message which would become his epitaph:

Robeson would later write the struggle against fascism during the Spanish Civil War was a turning point in his life, transforming him into a political activist and artist. In 1937, he used his concert performances to advocate the Republican cause and the war’s refugees. He permanently modified his renditions of Ol’ Man River from a show tune into a battle hymn of unwavering defiance. His business agent expressed concern about his political involvement, but Robeson overruled him and decided that contemporary events trumped commercialism In Wales, he commemorated the Welsh killed while fighting for the Republicans, where he recorded a message which would become his epitaph:

“The artist must take sides. He must elect to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative.”

After an invitation from J. B. S. Haldane, he traveled to Spain in 1938 because he believed in the International Brigades‘s cause. He visited the battlefront and provided a morale boost to the Republicans at a time when their victory was unlikely. Back in England, he hosted Jawaharlal Nehru to support Indian independence, wherein Nehru expounded on imperialism‘s affiliation with Fascism. Robeson reevaluated the direction of his career and decided to focus his attention on utilizing his talents to promote causes which he cherished. and subsequently appeared in Plant in the Sun by Herbert Marshall.

Political activism (1939–1958) – Outbreak of World War II (1939–1943)

Robeson leading Moore Shipyard Oakland, California workers in singing the Star Spangled Banner, September 1942. Robeson himself was a shipyard worker in World War I.

After the outbreak of World War II, Robeson returned to the US and became America’s “no.1 entertainer”with Ballad for Americans, and The Proud Valley—the film he was most proud of. At the Beverly Wilshire, the only hotel in Los Angeles willing to accommodate him, he spent two hours every afternoon sitting in the lobby. When asked why, he responded, “To ensure that the next time Black[s] come through, they’ll have a place to stay.”

With Max Yergan, Robeson co-founded the CAA. The CAA provided information about Africa across the US, particularly to African-Americans. It functioned as a coalition that included activists from varying leftist backgrounds. After Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, he participated in benefit concerts on behalf of the war effort.

He performed in Native Land, labeled “a Communist project” which was based on the La Follette Committee‘s investigation of the repression of labor organizations. He participated in the Tales of Manhattan, which he felt was “very offensive to my people”, and consequently he announced that he would no longer act in films because of the demeaning roles available to black[s]. He performed at the Polo Grounds to support the USSR in the war, where he met two emissaries from the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, Solomon Mikhoels and Itzik Feffer, an NKVDinformant.

The Broadway Othello and political activism (1943–1945)

Paul Robeson with Uta Hagen in the Theatre Guild production of Othello (1943–4).

Robeson reprised his role of Othello at the Shubert Theatre in 1943 under the direction of Margaret Webster. Stage actress Uta Hagen played Desdemona, and José Ferrer played Iago. He became the first African-American to play the role with a white supporting cast on Broadway where it was immensely popular. Contemporaneously, he addressed a meeting of Major League Baseball (MLB) club owners and MLB Commissioner Landis in a failed attempt to have them admit black players. Subsequently, he toured North America with Othello until 1945, received a Donaldson Award and was awarded the Spingarn medal by the NAACP.

Onset of Cold War (1946–1948)

In 1946, he opposed a move by the Canadian government to deport thousands of Japanese Canadians, and he telegraphed President Truman on the Lynching in the United States of four African Americans, demanding that the federal government “take steps to apprehend and punish the perpetrators … and to halt the rising tide of lynchings. He led a delegation to the White House to present a legislative and educational program aimed at ending mob violence; demanding that lynchers be prosecuted and calling on Congress to enact a federal anti-lynching law. He then warned Truman that if the government did not do something to end lynching, “the Negroes will.” Truman refused his request to issue a formal public statement against lynching, stating that it was not “the right time”. Robeson also gave a radio address, calling on all Americans of all races to demand that Congress pass civil rights legislation.

The CAA’s most successful campaign was for South African famine relief in 1946.

On October 7, 1946, he testified before the Tenney Committee that he was not a Communist Party member. The Civil Rights Congress (CRC) and the CAA was placed on the Attorney General’s List of Subversive Organizations (AGLOSO).

Robeson sang and spoke in 1948 at an event organized by the Los Angeles CRC and labor unions to launch a campaign against job discrimination, for passage of the federal Fair Employment Practices Act also known as Executive Order 8802, anti-lynching and anti-poll tax legislation, and citizens’ action to defeat the county loyalty oath climate.

In 1948, Robeson was preeminent in the campaign to elect Progressive Party presidential candidate Henry A. Wallace, who had served as Vice President under Franklin D. Roosevelt. Wallace was running on an anti-lynching, pro-civil rights platform and had attracted a diverse group of voters including Communists, liberals and trade unionists. On the campaign trail, Robeson went to the Deep South, where he performed for “overflow audiences… in Negro churches in Atlanta and Macon.”

Robeson’s belief that the labor movement and trade unionism were crucial to the civil rights of oppressed people of all races became central to his political beliefs. Robeson’s close friend, the union activist Revels Cayton, pressed for “black caucuses” in each union, with Robeson’s encouragement and involvement.

In 1948, he opposed a bill calling for registration of Communist Party members and appeared before the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary. Questioned about his affiliation with the Communist Party, he refused to answer, stating “Some of the most brilliant and distinguished Americans are about to go to jail for the failure to answer that question, and I am going to join them, if necessary.”