Missouri

Expedition St Louis

The History of Missouri begins with France and Spain settling the Louisiana territory and selling it to the U.S. in 1803. Statehood came following a compromise in 1820. Missouri grew rapidly until the Civil War, which saw numerous small battles and control by the Union. Its economy has become diverse and complex, and the state ranks in the middle of many economic and social indicators.

European exploration and colonization: 1673–1820 – Explorations and indigenous peoples

Map of the Marquette-Jolliet expedition of 1673 showing the first use of the word Missouri

Map of the Marquette-Jolliet expedition of 1673 showing the first use of the word Missouri

In May 1673, Jesuit priest Jacques Marquette and French trader Louis Jolliet sailed down the Mississippi River in canoes along the area that would later become the state ofMissouri. The earliest recorded use of “Missouri” is found on a map drawn by Marquette after his 1673 journey, naming both a group of Native Americans and a nearby river. However, the French rarely used the word to refer to the land in the region, instead calling it part of the Illinois Country. In 1682, after his successful journey from the Great Lakes to the mouth of the Mississippi River at the Gulf of Mexico, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle claimed the Louisiana Territory for France. During the journey, La Salle built several trading posts in the Illinois Country in an effort to create a trading empire; however, before La Salle could fully implement his plans, he died on a second journey to the region during a mutiny in 1685.

During the late 1680s and 1690s, the French pursued colonization of central North America not only to promote trade, but also to thwart the efforts of England on the continent. In that vein, Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville and Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienvilleestablished Biloxi in 1699 and Mobile in 1701 along the Gulf coast, while Antoine Laumet de La Mothe, sieur de Cadillac established Detroit in 1701 along the Great Lakes. From these outposts departed a variety of fur traders and Jesuit missionaries that enabled France to build strong relationships with indigenous tribes and retain control of the continental interior.

Although both Marquette and La Salle had passed Missouri on their journeys, neither had established bases of operations in what would become the state. Encouraged by the building of Mobile and Biloxi, the first to do so was Pierre Gabriel Marest, a Jesuit priest who in late 1700 established a mission on the west bank of the Mississippi at the mouth of the River Des Peres. Marest established his mission station with a handful of French settlers and a large band of the Kaskaskia people, who fled from the eastern Illinois Country to the station in the hope of receiving French protection from the Iroquois. Marest became involved in learning their language and constructed several cabins, a chapel, and a basic fort at the station. However, bands of Sioux were angry at the encroachment of the Kaskaskia onto Sioux lands at Des Peres; these Sioux forced Marest to move the station south and east in 1703 to a new location in Illinois known asKaskaskia.[5]

From this time up until the building of the first railways in the Mississippi Basin in the mid-19th century, the Mississippi-Missouri river system waterways were the main means of communication and transportation in the region. The earliest traffic up the Missouri likely occurred in the 1680’s by unlicensed fur traders; the first known ascent occurred in 1693, and within a decade, more than a hundred traders were moving along the Mississippi and Missouri. These early traders met two tribes within what would become Missouri: the Missouri and the Osage.

The Missouri were a semisedentary people with a major village along the Missouri River in northern Saline County, Missouri; they lived at the village primarily during the spring planting and fall harvesting seasons, while pursued game at other time. The Missouri became an ally of the French, eventually even traveling to Detroit to assist in the defense of the town against a Fox tribe attack. The Osage for their part became a more significant player in the development of Missouri history; they lived along the Osage River inVernon County, Missouri and near the Missouri village in Saline County. Like the Missouri, the Osage lived in semi-permanent villages, and they also both had acquired horses.

The exposure to French activities brought significant changes to the indigenous peoples of Missouri. Although interactions were generally positive between them, the introduction of diseases, alcohol, and firearms proved detrimental to traditional lifestyles and cultures. The increased dependence on European goods altered cultural patterns of craft production, and an increased emphasis on hunting due to commercialism changed Osage marriage patterns. Younger Osage hunters who had achieved wealth from trade sought to increase their power in Osage society, and they at various times challenged the established political order of tribal elders. Although both the Osage and the Missouri were exposed to European diseases such as smallpox and typhus, the Osage suffered only slightly compared to the Missouri, who were drastically reduced in population.

Founding of European settlements

During the 1710s, the French government again began to pursue a course of increased development of Louisiana. In August 1717, King Louis XV accepted the offer of Scottish financier John Law to create a joint stock company to manage colonial growth. Law’s Mississippi Company (renamed the Company of the West in 1717 upon receiving its charter) was given a monopoly on all trade, ownership of all mines, and use of all military posts in Louisiana in return for a ten-year requirement to settle 6,000 white settlers and 3,000 black slaves in the territory. The Illinois Country (which included Missouri) was also to be part of the charter. Investment in the company began in earnest, and in 1719, Law merged the Company of the West with several other joint stock companies to form the Company of the Indies. Appointed as provincial governor of Louisiana by the company, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville founded the city of New Orleans in 1718, and the company appointed Pierre Dugué de Boisbriand as commander of the Illinois Country.

The location of Mine La Motte, the first mine in Missouri, opened by Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac in the 1710’s and later expanded by Philip Francois Renault.

The location of Mine La Motte, the first mine in Missouri, opened by Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac in the 1710’s and later expanded by Philip Francois Renault.

After Boisbriand’s arrival in the Illinois Country, he ordered the construction of Fort de Chartres about eighteen miles north of Kaskaskia as the base of operations and headquarters for the company in the area. After the construction of Fort de Chartres, the company directed a series of prospecting expeditions to an area 30 miles west of the Mississippi River in present-day Madison, St. Francois, and Washington counties. These mining operations generally focused on discovering either lead or silver ore; the company appointed Philip Francois Renault as commander of the mines, and in 1723 Boisbriand ceded land to Renault in Washington County (in an area now known as the Old Mines) and in the Mine La Motte area. Because of the unappealing nature of mine work, white laborers demanded high wages; in response, Renault brought five black slaves to work in the mines, the first black slaves in Missouri. Despite these efforts, weather and hostility among indigenous tribes slowed production, and Renault sold his lands in 1742 having made little profit.

Despite severe financial losses in late 1720, in January 1722 the company’s directors sent Étienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont to Missouri to protect the company’s trade networks on the Missouri River from Spanish influence. Bourgmont arrived in New Orleans in September 1722, and he departed from the city for Missouri in February 1723 with a poorly equipped force. In November 1723, Bourgmont and the party arrived in present-day Carroll County in northern Missouri, where they constructed Fort Orleans. Within a year, Bourgmont negotiated alliances with indigenous tribes along the Missouri River, and in 1725, he brought a party of them to Paris to visit the French royal court. Bourgmont remained in France when the party returned to North America, and Fort Orleans was abandoned by the company in 1728. The quick abandonment of the fort after its construction was necessitated by the general retreat on the part of the company after the financial losses of 1720, and in 1731, the company returned its charter and control of Louisiana to royal authority.

During the 1730’s and 1740’s, French control over Missouri remained weak, and no permanent settlements existed on the western bank of the Mississippi River.’ Despite this lack of permanence, French fur traders continued to ascend the Missouri River and interact with indigenous peoples; one such duo, Paul and Pierre Mallet, journeyed from Missouri to Santa Fe, New Mexico in 1739, although future expeditions to New Spain were stopped by Spanish officials. In 1744, the French commander of Fort de Chartres gave five years of fur trading rights along the Missouri River to Joseph Deruisseau, who built a small fort (Fort de Cavagnal) on the Missouri River near present-day Kansas City, Missouri. However, the trading post never grew into a full-fledged settlement, and it disappeared by 1764.

French settlers remained on the east bank of the Mississippi at Kaskaskia and Fort de Chartres until 1750, when the new settlement of Ste. Genevieve, Missouri was constructed. During its early years, Ste. Genevieve grew slowly due to its location on a muddy, flat, floodplain, and in 1752, the town had only 23 full-time residents. Despite its proximity to lead mines and salt springs, the majority of its population came as farmers during the 1750s and 1760s, and they primarily grew wheat, corn and tobacco.

French and Indian War and the transfer to Spain

Map of early Missouri settlements and trading posts

Map of early Missouri settlements and trading posts

Shortly after the foundation of Ste. Genevieve, disputes between France and England over control of the Ohio Valley resulted in the outbreak of the French and Indian War in 1754 (known as the Seven Years’ War in Europe). The successful English attack on Quebec in 1759 and on Montreal in 1760 virtually guaranteed the loss of French Canada, although France remained in control of Missouri and the rest of the Illinois Country. In January 1762, Spain joined with France against England, but the war quickly turned against them for England. To persuade Spain to sign a peace settlement with England and to compensate for Spanish losses in the war, France secretly offered Spain control of Louisiana in November 1762 in the Treaty of Fontainebleau. In addition to the loss of Louisiana in the Treaty of Fontainebleau, the final settlement with England, known as the Treaty of Paris, transferred Canada from French to English control.

However, due to slow transit times, word of the Treaty of Fontainebleau did not arrive in Louisiana until 1765; in that period, the French governor of Louisiana granted a trade monopoly over Missouri to New Orleans merchant Gilbert Antoine de St. Maxent and his partner, Pierre Laclède. In August 1763, Laclede and his stepson Auguste Chouteau departed New Orleans for Missouri, where in February 1764 they established St. Louis on high bluffs overlooking the Mississippi.

Although Laclede had brought the news in December 1763 of the transfer of the eastern Illinois Country to the United Kingdom, the French commander Pierre Joseph Neyon de Villiers only received his orders to begin evacuations in April 1764. Villiers departed for New Orleans in June 1764 with 80 families, and he transferred temporary control to his subordinate, Louis St. Ange de Bellerive, who was given responsibility to monitor the remaining settlers in Illinois. Concern about living under British rule led many French settlers to decamp for Missouri, especially with encouragement from Laclede; upon the arrival of the British at Fort de Chartres in October 1765, St. Ange himself departed for St. Louis, where he took temporary command until Spanish representatives could take official control. From that point through the arrival of the Spanish in St. Louis in September 1767, St. Ange was the interim commander of the entire upper Louisiana region.

The first Spanish governor of Louisiana, Antonio de Ulloa, arrived in New Orleans in March 1766, and in early 1767 he dispatched his subordinate, Francisco Riu, to replace St. Ange as commander of a soon-to-be-built fort at the mouth of the Missouri River. St. Ange, however, remained the administrative authority in the town and south of the Missouri River. The fort that Ulloa had ordered built, known as Fort Don Carlos, ultimately was constructed on the southern bank of the Missouri; however, disputes during the construction led to the dismissal of Riu and his replacement by Pedro Piernas in August 1768.

Weather and ice delayed Piernas’s ascent to Fort Don Carlos through April 1769; between his arrival and his departure, the Louisiana Rebellion of 1768 broke out in New Orleans against Spanish rule, and Ulloa was forced to flee. Only 13 days after his arrival to Fort Don Carlos, Piernas received orders to evacuate the fort and return control to St. Ange. When Piernas and his garrison left Louisiana in July 1769, they were the last Spanish forces to leave the territory. Spanish officials acted quickly to crush the rebellion, however, and in August 1769, resistance collapsed. Although the rebellion led to the execution of five rebel leaders in New Orleans, no reprisals were necessary or occurred in Missouri.

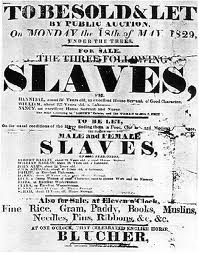

Slavery in Missouri

Rich planters from Kentucky and Tennessee moved into the bottomland of “Little Dixie” region in the central part of the state. They bought up large tracts of fertile land, and brought in slaves to do the work of growing hemp (for rope making) and tobacco, traditional crops of the Upper South. Slaves were expensive, with the average price of $700 in 1860, the equivalent of three or four years’ pay for a free worker. In most of the state, slavery was unprofitable, and in 7/8 of the counties, farmers had no slaves. Burke, looking microscopically at slaves living on farms and town along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, is able to study the economics of slavery, relations between slaves and owners, the challenges faced by slave families and hos they raised their children, sociability among enslaved and free Missourians, and the collapse of slavery during the Civil War. She finds that slavery in Missouri had an especially intimate quality as owners directly oversaw their slaves (without overseers), worked alongside them every day, and lived in the same or adjacent houses. The owners claimed this made for a milder version of bondage. Some slaves, who expressed fear of being sold further south, agreed.

Rich planters from Kentucky and Tennessee moved into the bottomland of “Little Dixie” region in the central part of the state. They bought up large tracts of fertile land, and brought in slaves to do the work of growing hemp (for rope making) and tobacco, traditional crops of the Upper South. Slaves were expensive, with the average price of $700 in 1860, the equivalent of three or four years’ pay for a free worker. In most of the state, slavery was unprofitable, and in 7/8 of the counties, farmers had no slaves. Burke, looking microscopically at slaves living on farms and town along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, is able to study the economics of slavery, relations between slaves and owners, the challenges faced by slave families and hos they raised their children, sociability among enslaved and free Missourians, and the collapse of slavery during the Civil War. She finds that slavery in Missouri had an especially intimate quality as owners directly oversaw their slaves (without overseers), worked alongside them every day, and lived in the same or adjacent houses. The owners claimed this made for a milder version of bondage. Some slaves, who expressed fear of being sold further south, agreed.

In 1824, the Missouri State Supreme Court ruled that free blacks could not be re-enslaved, a principle known as “once free, always free.” In 1846, the Dred Scott v. Sandford case began. Dred and Harriet Scott, who were slaves, sued for freedom in state courts. This was on the premise that they had previously lived in a free state. This case continued until 1857, culminating in a landmark United States Supreme Court decision rejecting Scott’s arguments and sustaining slavery. In 1860, 3600 free blacks lived in Missouri.

The proportion of slaves in the state population peaked at 18 percent in 1830; by 1860 the proportion was 9.8 percent in 1860, following heavy Irish and German immigration from the 1840s, as well as continued migration from the eastern United States. In St. Louis, nine percent of the 14,000 residents in 1840 were slaves, and only one percent of the 57,000 residents in 1860, Although few Missouri families owned slaves, many whites of southern origin thought that slavery was basically a good idea, and that freeing the slaves would be a calamity for the white population. The state officially abolished slavery in January 1865 when the governor signed the Ordinance of Emancipation.