Mississippi

Exploring History: Corinth, Mississippi and Shiloh National Military Park

“Exploring History: Corinth, Mississippi and Shiloh National Military Park” looks at two southern locations important to the outcome of the American Civil War and the years following. Explore Corinth, Mississippi and the Battle of Shiloh along with a group of students from the area. The state of Mississippi‘s history goes back beyond American statehood to ancient Native American times.

Native Americans

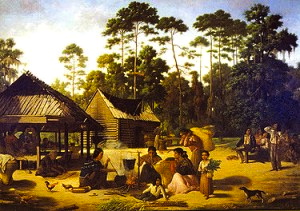

Choctaw Village near the Chefuncte by Francois Bernard, 1869, Peabody Museum Harvard University. The women are preparing dye to color cane strips for making baskets.

Choctaw Village near the Chefuncte by Francois Bernard, 1869, Peabody Museum Harvard University. The women are preparing dye to color cane strips for making baskets.

At the end of the last Ice Age Native American or Paleo-Indiansappeared in what today is the South. Paleo Indians in the South were hunter-gatherers who pursued the mega fauna that became extinct following the end of the Pleistocene age. After thousands of years, the Paleo Indians developed a rich agricultural society. Archeologists called these people the Mississippians of the Mississippian culture.

Descendant Native American tribes include the Chickasaw andChoctaw. Other tribes who inhabited the territory of Mississippi (and whose names became those of local towns) include the Natchez, the Yazoo, the Pascagoula, and the Biloxi.

European colonial period

The first major European expedition into the territory that became Mississippi was that of Hernando de Soto who passed through in 1540. The French claimed the territory that included Mississippi as part of their colony of New France and started settlement. They created the first Fort Maurepas under Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville on the site of modern Ocean Springs (or Old Biloxi) in 1699.

In 1716, the French founded Natchez as Fort Rosalie; it became the dominant town and trading post of the area. In the early 18th century, the Roman Catholic Church created pioneer parishes at Old Biloxi/Ocean Springs and Natchez. The church also established seven pioneer parishes in Louisiana and two in Alabama, which was also part of New France.

The French and later Spanish colonial rule influenced early social relations of the settlers who held enslaved Africans. As in Louisiana, for a period there grew a third class of free people of color, whose origin was chiefly as descendants of white planters and enslaved African or African-American mothers. The planters often had formally supportive relationships with their mistresses of color and arranged for freedom for them and their multiracial children. The fathers sometimes passed on property or arranged for the apprenticeship or education of children so they could learn a trade. Free people of color often migrated to New Orleans, where there was more opportunity for work and a bigger community.

Like Louisiana as part of New France, Mississippi was alternately ruled by Spanish, and British. In 1783 the Mississippi area was deeded by Great Britain to the United States after the American Revolution under the terms of the Treaty of Paris.

Territory and statehood

Before 1798 the state of Georgia claimed the entire region between the Mississippi and Chattahoochee rivers and tried to sell lands there, most notoriously in the Yazoo land scandal of 1795. Georgia finally ceded the disputed area in 1805 to the national government; in 1804 the northern part of the cession was added to Mississippi Territory.

The Mississippi Territory was sparsely populated and suffered initially from a series of difficulties that hampered its development. Pinckney’s Treaty of 1795 ended Spanish control over Mississippi but Spain continued to hamper the territory’s growth by harassing commercial traders. Winthrop Sargent, governor in 1798, proved unable to impose a code of laws. Not until the emergence of cotton as a profitable staple crop and the accompanying rise of slave labor did Mississippi begin to flourish.

The Mississippi Territory was sparsely populated and suffered initially from a series of difficulties that hampered its development. Pinckney’s Treaty of 1795 ended Spanish control over Mississippi but Spain continued to hamper the territory’s growth by harassing commercial traders. Winthrop Sargent, governor in 1798, proved unable to impose a code of laws. Not until the emergence of cotton as a profitable staple crop and the accompanying rise of slave labor did Mississippi begin to flourish.

There were land disputes with the Spanish, and in 1810 the settlers in parts of West Florida rebelled and declared their freedom from Spain. President James Madison declared that the region between the Mississippi and Perdido rivers, which included most of West Florida, had already become part of the United States under the terms of the Louisiana Purchase. The section of West Florida between the Pearl and Perdido rivers, known as the District of Mobile, was annexed to Mississippi Territory in 1812; Americans occupied Kiln, MS in 1813.

Settlement

The attraction of vast amounts of high quality, inexpensive cotton land attracted hordes of settlers, mostly from Georgia and the Carolinas and from tobacco areas of Virginia and North Carolina at a time when growing tobacco barely made a profit. From 1798 through 1820 the population soared from less than 9,000 to more than 222,000. Migration came in two fairly distinct waves – a steady movement until the outbreak of the War of 1812 and a flood from 1815 through 1819. The postwar flood was caused by various factors including high prices for cotton, the elimination of Indian titles to much land, new and improved roads, and the acquisition of new direct outlets to the Gulf of Mexico. The first migrants were traders and trappers, then herdsmen, and finally farmers. The Southwest frontier produced a relatively democratic society.

Cotton

After 1800 the development of a cotton economy in the South changed the economic relationship of native Indians with whites and slaves in Mississippi Territory. As Indians ceded their lands to whites, they became more isolated from whites and blacks. A great wave of public sales of former Indian land plus white migration (with slaves) into Mississippi Territory guaranteed the dominance of the developing cotton agriculture.

Statehood

In 1817 elected delegates wrote a constitution and applied to Congress for statehood. On Dec. 10, 1817, the western portion of Mississippi Territory became the State of Mississippi, the 20th state of the Union. Natchez was the first state capital; the capital was moved to Jackson in 1822.

Religion

While the Catholic Church was active along the coast, Protestant religious activities began inland in the Mississippi Territory after 1799. Methodists, Baptists, and Presbyterians formed the three leading denominations in the territory. Deism and other religions were also present, but in smaller numbers. Protestant ministers won converts, often promoted education, and had some influence in improving the treatment of slaves.

Government

William C. C. Claiborne (1775–1817), a lawyer and former Republican Congressman from Tennessee (1797–1801), was governor and superintendent of Indian affairs in the Mississippi Territory from 1801 through 1803. Although he favored acquiring some land from the Choctaw and Chicasaw, Claiborne was generally sympathetic and conciliatory toward Indians. He worked long and patiently to iron out differences that arose, and to improve the material well-being of the Indians. He was also partly successful in promoting the establishment of law and order, as when his offering of a two thousand dollar reward helped destroy a gang of outlaws headed by Samuel Mason (1750–1803). His position on issues indicated a national rather than regional outlook, though he did not ignore his constituents. Claiborne expressed the philosophy of the Republican Party and helped that party defeat the Federalists. When a smallpox epidemic broke out in the spring of 1802, Claiborne’s actions resulted in the first recorded mass vaccination in the territory and saved Natchez from the disease.

Ante-Bellum

The exit of most the Native Americans meant that vast new lands were open to settlement, and tens of thousands of immigrant Americans poured in. Men with money brought slaves and purchased the best cotton lands in the “Delta” region along the Mississippi River. Poor men took up poor lands in the rest of the state.

Cotton

By the 1830s Mississippi was a leading cotton producer, and demands for slaves, on whom the crop depended, increased. They were considered a “necessary evil” for the survival of the cotton economy, and were brought in from the border states and the tobacco states where slavery was declining. The 1832 constitution forbade the further importation of slaves, but the provision was found to be unenforceable, and it was repealed. As planters increased their holdings of land and slaves, the price of land rose, and small farmers were driven into less fertile areas. An elite slave-owning class arose that wielded disproportionate political and economic power. By 1860, of the 354,000 whites, only 31,000 owned slaves and two thirds of these held fewer than 10. Fewer than 5,000 slaveholders had more than 20 slaves; 317 possessed more than 100. These 5000 planters controlled the state. In addition there was a middle element composed of farmers who owned land but no slaves, together with a small number of businessmen and professionals who lived in the villages and small towns. The lower class, or “poor whites,” occupied marginal farm lands remote from the rich cotton lands and grew food for their families, not cotton. Whether they owned slaves or not, however, most white Mississippians became both defensive and emotional on the subject of slavery. A slave insurrection scare in 1836 resulted in the hanging of a number of slaves and several white northerers suspected of being secret abolitionists.

When cotton was king during the 1850s, Mississippi plantation owners—especially those in the old Natchez District, as well as the newly emerging Delta and Black Belt regions—became increasingly wealthy due to the great fertility of the soil and the high price of cotton on the international market. The severe wealth imbalances and the necessity of large-scale slave populations to sustain such income played a heavy role in both state politics and in the support for secession.

Mississippi’s population grew rapidly, reaching 791,000 in 1860. Cotton production grew from 43,000 bales in 1820 to over one million bales in 1860, as Mississippi became the leading cotton-producing state. The textile factories of Britain, France and New England demanded more and more cotton, and little was grown outside the United States. In Mississippi some modernizers spoke of diversification, and vegetable and livestock production did increase, but King Cotton prevailed. Cotton’s ascendancy was seemingly justified in 1859, when Mississippi planters were scarcely touched by the financial panic in the North. They were concerned by inflation of the price of slaves but were in no real distress. Mississippi’s per capita wealth was well above the U.S. average. Planters made very lage profits, but they invested it on buying more cotton lands and more slaves, which pushed up prices even higher. They did not feel at all guilty about holding slaves. The threat of abolition troubled them, but they reassured themselves that if need be the cotton states could secede from the Union, form their own country, and expand to the south in Mexico and Cuba. Until late 1860 they never expected a war.

Slavery in Mississippi

From the black perspective, the majority were slaves living on plantations with 20 or more fellow slaves. The division of labor included an elite of house slaves, a middle group of overseers, drivers (gang leaders) and skilled craftsmen, and a “lower class” of unskilled field workers whose main job was hoeing and picking cotton. The owners hired white overseers to direct the work. Some slaves resisted by work slowdowns and by breaking tools and equipment. There were no slave revolts of any size, although whites often circulated fearful rumors that one was about to happen. Most of those who tried to escape were captured and returned, though a handful made it north to Illinois and freedom. Most slaves endured the harsh routine of plantation life, though some with special skills attained a quasi-free status. By 1820, 458 former slaves had been freed, but they were forbidden to have weapons and had to carry identification. In 1822 the awkwardness of free blacks living near slaves prompted a state law forbidding emancipation except by special act of the legislature. By 1860 only 1,000 of the 437,000 blacks were free, and most of these lived in wretched conditions near Natchez. The relatively low population of the state before the Civil War reflected the fact that much of the state was still wilderness and needed more settlers for development. Except for riverside settlements and plantations, 90% of the Mississippi Delta bottomlands was still undeveloped and covered mostly in mixed forest and swampland.

From the black perspective, the majority were slaves living on plantations with 20 or more fellow slaves. The division of labor included an elite of house slaves, a middle group of overseers, drivers (gang leaders) and skilled craftsmen, and a “lower class” of unskilled field workers whose main job was hoeing and picking cotton. The owners hired white overseers to direct the work. Some slaves resisted by work slowdowns and by breaking tools and equipment. There were no slave revolts of any size, although whites often circulated fearful rumors that one was about to happen. Most of those who tried to escape were captured and returned, though a handful made it north to Illinois and freedom. Most slaves endured the harsh routine of plantation life, though some with special skills attained a quasi-free status. By 1820, 458 former slaves had been freed, but they were forbidden to have weapons and had to carry identification. In 1822 the awkwardness of free blacks living near slaves prompted a state law forbidding emancipation except by special act of the legislature. By 1860 only 1,000 of the 437,000 blacks were free, and most of these lived in wretched conditions near Natchez. The relatively low population of the state before the Civil War reflected the fact that much of the state was still wilderness and needed more settlers for development. Except for riverside settlements and plantations, 90% of the Mississippi Delta bottomlands was still undeveloped and covered mostly in mixed forest and swampland.

Politics

Mississippi was a stronghold of Jacksonian Democracy, which glorified the independent farmer; they even named their state capital in Jackson’s honor. But dishonor was also rampant. Corruption and land speculation caused a severe blow to state credit in the years preceding the Civil War. Federally allocated funds were misused, tax collections embezzled, and finally, in 1853, two state-supported banks collapsed when their debts were repudiated. In the Second Party System (1820s to 1850s) Mississippi moved politically from a divided Whig and Democratic state to a one-party Democratic state bent on secession. Criticism from Northern abolitionists escalated after the Mexican War ended in 1848, causing an intense countercrusade that tried to identify and eliminate all dangerous abolitionist influences. White Mississippians became outspoken defenders of the slave system. An abortive secession attempt in 1850 was followed by a decade of political agitation during which the protection and expansion of slavery became their major goal. When Republican Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1860 with the goal seeking an eventual end of slavery, Mississippi followed South Carolina and seceded from the Union on Jan. 9, 1861. Mississippi’s U.S. senator Jefferson Davis became president of the Confederate States.

Civil War – See the main article Mississippi in the Civil War.

More than 80,000 Mississippians fought in the Civil War, and casualties were extremely heavy. Thousands of ex-slaves were enlisted in the Union Army. Fear that white supremacy might be lost, among a plethora of other reasons, motivated men to join the Confederate Army. The amount of personal property owned, including slaves, increased the likelihood that a man would volunteer. However, men in Mississippi’s river counties, regardless of their wealth or other characteristics, were less likely to join the army than were those living in the state’s interior. The river made its neighbors especially vulnerable, and river-county residents apparently left their communities (and often the Confederacy) rather than face invasion. The major military operations came in the Shiloh and Corinth campaigns and the siege of Vicksburg, from the spring of 1862 to the summer of 1863. The most important was them Vicksburg Campaign, fought for control of the last Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River. The fall of the city to General Ulysses S. Grant on July 4, 1863, gave the Union control of the Mississippi River, cut off the western states, and made the Confederate cause in the west hopeless.

More than 80,000 Mississippians fought in the Civil War, and casualties were extremely heavy. Thousands of ex-slaves were enlisted in the Union Army. Fear that white supremacy might be lost, among a plethora of other reasons, motivated men to join the Confederate Army. The amount of personal property owned, including slaves, increased the likelihood that a man would volunteer. However, men in Mississippi’s river counties, regardless of their wealth or other characteristics, were less likely to join the army than were those living in the state’s interior. The river made its neighbors especially vulnerable, and river-county residents apparently left their communities (and often the Confederacy) rather than face invasion. The major military operations came in the Shiloh and Corinth campaigns and the siege of Vicksburg, from the spring of 1862 to the summer of 1863. The most important was them Vicksburg Campaign, fought for control of the last Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River. The fall of the city to General Ulysses S. Grant on July 4, 1863, gave the Union control of the Mississippi River, cut off the western states, and made the Confederate cause in the west hopeless.

At the Battle of Grand Gulf Admiral Porter led seven Union ironclads in an attack on the fortifications and batteries at Grand Gulf, Mississippi, with the intention of silencing the Confederate guns and then securing the area with troops of McClernand’s XIII Corps who were on the accompanying transports and barges. The Confederates managed to win a hollow victory; the loss at Grand Gulf caused just a slight change in Grant’s offensive. Grant won the Battle of Port Gibson. Advancing towards Port Gibson, Grant’s army ran into Confederate outposts after midnight. Union forces advanced on the Rodney Road and a plantation road at dawn, and was met by Confederates. Grant forced the Confederates to fall back to new defensive positions several times during the day but they could not stop the Union onslaught and left the field in the early evening. This defeat demonstrated that the Confederates were unable to defend the Mississippi River line and the Federals had secured their beachhead. William Tecumseh Sherman‘s march from Vicksburg to Meridian was designed to destroy the railroad center of Meridian. The campaign was Sherman’s first application of total war tactics, prefiguring his March to the Sea in Georgia in 1864. The Confederates had no better luck at the Battle of Raymond. On May 10, 1863, Pemberton sent troops from Jackson to Raymond, 20 miles (32 km) to the southwest. Brig. Gen. over-strength brigade, having endured a grueling march from Port Hudson, Louisiana, arrived in Raymond late on May 11 and the next day tried to ambush a small Union raiding party. The raiding party turned out to be Maj. Gen. John A. Logan‘s Division of the XVII Corps. Gregg tried to hold Fourteen Mile Creek and a sharp battle ensued for six hours, but the overwhelming Union force prevailed and the Confederates retreated, exposing the Southern Railroad of Mississippi to Union forces, thus severing the lifeline of Vicksburg.

In April–May 1863 a major cavalry raid by Union colonel Benjamin H. Griersonraced through Mississippi and Louisiana, that destroying railroads, telegraph lines, and Confederate weapons and supplies. The raid also served as a diversion for Grant’s moves toward Vicksburg.

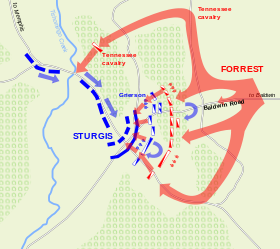

A Union expedition commanded by General Samuel D. Sturgis was opposed by Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest. They clashed at the Battle of Brice’s Crossroads on 10 June 1864, as Forrest routed the Yankees in his greatest battlefield victory.

Homefront

After each battle there was increased economic chaos and societal breakdown. State government during the course of the war was forced to move from Jackson to Enterprise, to Meridian and back to Jackson, to Meridian again and then to Columbus, Macon, and finally back to what was left of Jackson. The two wartime governors were fire-eater John J. Pettus, who carried the state into secession, whipped up the war spirit, began military and domestic mobilization, and prepared to finance the war. His successor, General Charles Clark, elected in 1863, although facing a deteriorating military and economic situation, remained committed to continuing the fight regardless of the cost. The war presented both men with enormous challenges in providing an orderly, stable government for Mississippi.

There were no slave insurrections, as plantations turned to food production. The Union presence made it possible for planters to sell their cotton to Union Treasury agents for high prices, a sort of treason the Confederates were unable to stop.

Most whites supported the Confederacy, but there were holdouts. The two most vehemently anti-Confederate areas in were Jones County in the southeastern corner of the state, where the “Knight Company” originated, and Tishomingo in the northeastern corner. Among the most influential Mississippi Unionists was Presbyterian minister John Aughey, whose sermons and book The Iron Furnace or Slavery and Secession (1863) became hallmarks of the anti-secessionist cause in the state.

The war shattered the lives of all classes, high and low. Upper class ladies replaced balls and parties with bandage-rolling sessions and fund-raising efforts. But soon enough they found their world shattering as they lost brothers, sons and husbands to battlefield deaths and disease, lost their incomes and luxuries and instead had to deal with chronic shortages and poor ersatz substitutes for common items. They took on unexpected responsibilities, including the chores always left to slaves; they coped by focusing on survival. They maintained their family honor by upholding Confederate patriotism to the bitter end, and after the war became the champions of the “Los Cause.” Less privileged white women were less wedded to honor and patriotism and in even more trouble as they immediately were forced to do double and triple work with the men gone; many became refugees in camps or fled to Union lines.

Black women and children had an especially hard time as the plantation regime collapsed and the only option was to find a refugee camp operated by the Union Army. Tens of thousands of freedmen died from cholera, yellow fever, diphtheria, dysentery, pneumonia, phthisis, convulsions, and other fevers. Death rates were especially high in informal refugee camps, and somewhat lower in the better-organized camps funt by the Freedman’s Bureau of the U.S. Army.

Reconstruction

After the defeat of the Confederacy, President Andrew Johnson appointed a temporary government under Judge William Lewis Sharkey. It repealed secession and wrote new Black Codes defining and limiting the civil rights of the African American freedmen as a sort of third class status without citizenship or voting rights. The Black Codes never took effect, however, since the legal affairs of the freedmen came under the control of sympathetic Freedman’s Bureau representatives. Most of them were former Army officers from the North. Many stayed in the state and became political and business leaders (scornfully known as “carpetbaggers“). The Black codes outraged northern opinion and apparently were never put into effect in any state.

Congress responded in September 1865 by refusing to seat the newly elected delegation. In 1867 it put Mississippi under U.S. Army rule as part of Reconstruction until the legal status of ex-Confederates and freedmen could be worked out. The military governor general Adelbert Ames deposed the civil government, enrolled black men as voters, and prohibited for a period of time 1000 or so former Confederate leaders to vote or hold office. The 1868 constitution had major elements that lasted for 22 years. The convention was the first political organization to include African American representatives, who numbered 17 among the 100 members. Although 32 counties had Negro majorities, they elected whites as well as Negroes to represent them. The convention adopted universal male suffrage; did away with property qualifications for suffrage or for office, which benefited poor whites, too; created the state’s first public school system; forbade race distinctions in the possession and inheritance of property; and prohibited limiting of civil rights in travel. Since 17 of the 100 delegates were blacks, the body was called the Black and Tan convention by its enemies. Mississippi was readmitted to Congress on Feb. 23, 1870.

Black Mississippians, participating in the political process for the first time ever, formed a coalition with some locals whites (called “Scalawags“) and newly arrived Northerners (called “Carpetbaggers“) in a Republican party that controlled the state. Most of its votes came from blacks, several of whom held important state offices. A. K. Davis served as lieutenant governor, Hiram Revels andBlanche K. Bruce were elected by the legislature to the U.S. Senate, and John R. Lynch served as a congressman. The Republican regime faced the determined opposition of the “unreconstructed” white population. Blacks who attempted to exercise their new rights were terrorized by such groups as the Ku Klux Klan.

The planter James Lusk Alcorn, a Confederate general, was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1865 but, like other Southerners who had been loyal to the Confederacy, was not allowed to take a seat. He supported suffrage for freedmen and endorsed the Fourteenth Amendment, as required by the Republicans in Congress. Alcorn became the leader of the scalawags, who comprised about a third of the Republican party in the state, in coalition with carpetbaggers and freedmen.

On 1869 Alcorn was elected as governor in 1869 and served from 1870 to 1871. As a modernizer, he appointed many like-minded former Whigs, even if they were now Democrats. He strongly supported education, including segregated public schools, and a new college for freedmen, now known as Alcorn State University. He maneuvered to make his ally Hiram Revels its president. Radical Republicans opposed Alcorn as they were angry about his patronage policy. One complained that Alcorn’s policy was to see “the old civilization of the South modernized” rather than lead a total political, social and economic revolution.

Alcorn resigned the governorship to become a U.S. Senator (1871–1877), replacing his ally Hiram Revels, the first African American senator. Senator Alcorn urged the removal of the political disabilities of white southerners and rejected Radical Republican proposals to enforce social equality by Federal legislation Further, he denounced the Federal cotton tax as robbery, and defended separate schools for both races in Mississippi. Although a former slaveholder, he characterized slavery as “a cancer upon the body of the Nation” and expressed gratification which he felt over its destruction.

In 1870 former military governor Adelbert Ames was elected to the U.S. Senate. Ames and Alcorn battled for control of the Republican party in Mississippi; their struggle ripped apart the Republican party. In 1873 they both sought a decision by running for governor. Ames was supported by the Radicals and most African Americans, while Alcorn won the votes of conservative whites and most of the scalawags. Ames won by a vote of 69,870 to 50,490. A riot broke out in Vicksburg in December 1873 that started a series of reprisals against many Republican supporters, the vast majority of them black. There was factionalism within the Democratic Party between the Regulars and New Departures, but as the state election of 1875 approached, the Democrats untied and brought out the “Mississippi Plan” which called for the systematic organization of all whites to defeat the Republicans. Armed attacks by the Red Shirts and White League on Republican activists proliferated, and Governor Ames appealed to the federal government for assistance, which was refused. That November, Democrats gained firm control of both houses of the legislature. Ames requested the intervention of the U.S. Congress since he believed that the election was full of voter intimidation and fraud. The state legislature, convening in 1876, drew up articles of impeachment against him and all statewide officials. He resigned a few months after the legislature agreed to drop the articles against him.