Minstrel Show

Al Jolson Blackface Minstrel Show

Al Jolson plays blackface minstrel performer EP Christy in “Swanee River” (1939). Jolson got his start in minstrel shows and was the most famous minstrel artist of his era. In this clip, Jolson sings Oh! Susanna and Swanee River. Read about the history of blackface and minstrel shows at http://black-face.com

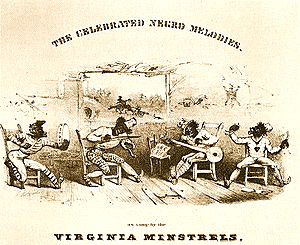

Detail from cover of The Celebrated Negro Melodies, as Sung by the Virginia Minstrels, 1843

Detail from cover of The Celebrated Negro Melodies, as Sung by the Virginia Minstrels, 1843

The minstrel show, or minstrelsy, was an American form of entertainment developed in the 19th century. It was a form of entertainment that required payment to attend. Each show consisted of comic skits, variety acts, dancing, and music, performed by white people in make-up or blackface for the purpose of playing the role of black people.

Minstrel shows lampooned black people as dim-witted, lazy, buffoonish, superstitious, happy-go-lucky, and musical. The minstrel show began with brief burlesques and comic entr’actes in the early 1830’s and emerged as a full-fledged form in the next decade. By 1848, blackface minstrel shows were the national artform, translating formal art such as opera into popular terms for a general audience.

By the turn of the 20th century, the minstrel show enjoyed but a shadow of its former popularity, having been replaced for the most part by vaudeville. It survived as professional entertainment until about 1910; amateur performances continued until the 1960’s in high schools and local theaters. As the civil rights movement progressed and gained acceptance, minstrels lost popularity.

The typical minstrel performance followed a three-act structure. The troupe first danced onto stage then exchanged wisecracks and sang songs. The second part featured a variety of entertainments, including the pun-filled stump speech. The final act consisted of a slapstick musical plantation skit or a send-up of a popular play. Minstrel songs and sketches featured several stock characters, most popularly the slave and the dandy. These were further divided into sub-archetypes such as the mammy, her counterpart the old darky, the provocative mulatto wench, and the black soldier. Minstrels claimed that their songs and dances were authentically black, although the extent of the black influence remains debated. Spirituals (known as jubilees) entered the repertoire in the 1870’s, marking the first undeniably black music to be used in minstrelsy.

Blackface minstrelsy was the first theatrical form that was distinctly American. During the 1830’s and 1840s at the height of its popularity, it was at the epicenter of the American music industry. For several decades it provided the means through which American whites viewed black people. On the one hand, it had strong racist aspects; on the other, it afforded white Americans a singular and broad awareness of what some whites considered significant aspects of black culture in America.

Although the minstrel shows were extremely popular, being “consistently packed with families from all walks of life and every ethnic group,” they were also controversial. Racial integrationists decried them as falsely showing happy slaves while at the same time making fun of them; segregationists thought such shows were “disrespectful” of social norms, portrayed runaway slaves with sympathy and would undermine the southerners’ “peculiar institution.”

History – Early Development

Thomas D. Rice from sheet music cover of “Sich a Getting Up Stairs,” 1830’s

Thomas D. Rice from sheet music cover of “Sich a Getting Up Stairs,” 1830’s

Minstrel shows were popular before slavery was abolished, sufficiently so that Frederick Douglass described blackface performers as “… the filthy scum of white society, who have stolen from us a complexion denied them by nature, in which to make money, and pander to the corrupt taste of their white fellow citizens.” Although white theatrical portrayals of black characters date back to as early as 1604, the minstrel show as such has later origins. By the late 18th century, blackface characters began appearing on the American stage, usually as “servant” types whose roles did little more than provide some element of comic relief. Eventually, similar performers appeared in entr’actes in New York theaters and other venues such as taverns and circuses. As a result, the blackface “Sambo” character came to supplant the “tall-tale-telling Yankee” and “frontiersman” character-types in popularity, and white actors such as Charles Mathews, George Washington Dixon, and Edwin Forrest began to build reputations as blackface performers. Author Constance Rourke even claimed that Forrest’s impression was so good he could fool blacks when he mingled with them in the streets.

Thomas Dartmouth Rice’s successful song-and-dance number, “Jump Jim Crow,” brought blackface performance to a new level of prominence in the early 1830s. At the height of Rice’s success, The Boston Post wrote, “The two most popular characters in the world at the present are [Queen] Victoria and Jim Crow.” As early as the 1820s, blackface performers called themselves “Ethiopian delineators;” from then into the early 1840s, unlike the later heyday of minstrelsy, they performed either solo or in small teams.

Blackface soon found a home in the taverns of New York’s less respectable precincts of Lower Broadway, the Bowery, and Chatham Street. It also appeared on more respectable stages, most often as an entr’acte. Upper-class houses at first limited the number of such acts they would show, but beginning in 1841, blackface performers frequently took to the stage at even the classy Park Theatre, much to the dismay of some patrons. Theater was a participatory activity, and the lower classes came to dominate the playhouse. They threw things at actors or orchestras who performed unpopular material, and rowdy audiences eventually prevented the Bowery Theatre from staging high drama at all. Typical blackface acts of the period were short burlesques, often with mock Shakespearean titles like “Hamlet the Dainty”, “Bad Breath, the Crane of Chowder,” “Julius Sneezer” or “Dars-de-Money.”

Meanwhile, at least some whites were interested in black song and dance by actual black performers. Nineteenth-century New York slaves shingle danced for spare change on their days off, and musicians played what they claimed to be “Negro music” on so-called black instruments like the banjo.[citation needed] The New Orleans Picayune wrote that a singing New Orleans street vendor called Old Corn Meal would bring “a fortune to any man who would start on a professional tour with him.”Rice responded by adding a “Corn Meal” skit to his act. Meanwhile, there had been several attempts at legitimate black stage performance, the most ambitious probably being New York’s African Grove theater, founded and operated by free blacks in 1821, with a repertoire drawing heavily on Shakespeare. A rival theater company paid people to “riot” and cause disturbances at the theater, and it was shut down by the police when neighbors complained of the commotion.

White, working-class Northerners could identify with the characters portrayed in early blackface performances. This coincided with the rise of groups struggling for workingman’s nativism and pro-Southern causes, and faux black performances came to confirm pre-existing racist concepts and to establish new ones. Following a pattern that had been pioneered by Rice, minstrelsy united workers and “class superiors” against a common black enemy, symbolized especially by the character of the black dandy. In this same period, the class-conscious but racially inclusive rhetoric of “wage slavery” was largely supplanted by a racist one of “white slavery.” This suggested that the abuses against northern factory workers were a graver ill than the treatment of black slaves—or by a less class-conscious rhetoric of “productive” versus “unproductive” elements of society. On the other hand, views on slavery were fairly evenly presented in minstrelsy, and some songs even suggested the creation of a coalition of working blacks and whites to end the institution.

Among the appeals and racial stereotypes of early blackface performance were the pleasure of the grotesque and its infantilization of blacks. These allowed—by proxy, and without full identification—childish fun and other low pleasures in an industrializing world where workers were increasingly expected to abandon such things. Meanwhile, the more respectable could view the vulgar audience itself as a spectacle.

Height

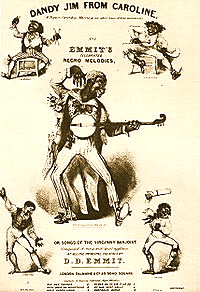

Sheet music cover for “Dandy Jim from Caroline,” featuring Dan Emmett (center) and the other Virginia Minstrels, c. 1844

Sheet music cover for “Dandy Jim from Caroline,” featuring Dan Emmett (center) and the other Virginia Minstrels, c. 1844

With the Panic of 1837, theater attendance suffered, and concerts were one of the few attractions that could still make money. In 1843, four blackface performers led by Dan Emmett combined to stage just such a concert at the New York Bowery Amphitheatre, calling themselves the Virginia Minstrels. The minstrel show as a complete evening’s entertainment was born. The show had little structure. The four sat in a semicircle, played songs, and traded wisecracks. One gave a stump speech in dialect, and they ended with a lively plantation song. The term minstrel had previously been reserved for traveling white singing groups, but Emmett and company made it synonymous with blackface performance, and by using it, signalled that they were reaching out to a new, middle-class audience.

The Herald wrote that the production was “entirely exempt from the vulgarities and other objectionable features, which have hitherto characterized negro extravaganzas.” In 1845, the Ethiopian Serenaders purged their show of low humor and surpassed the Virginia Minstrels in popularity. Shortly thereafter, Edwin Pearce Christy founded Christy’s Minstrels, combining the refined singing of the Ethiopian Serenaders (epitomized by the work of Christy’s composer Stephen Foster) with the Virginia Minstrels’ bawdy schtick. Christy’s company established the three-act template into which minstrel shows would fall for the next few decades. This change to respectability prompted theater owners to enforce new rules to make playhouses calmer and quieter.