Mao Zedong

Chairman Mao Documentary – The Cultural Revolution – Destruction Of China

Mao Zedong was a very practical person before 1949. He did many thorough investigations about China and he developed his theories based on his studies. He was so successful in his early years that people worshipped him and everyone loved him. Things changed after 1949. Mao was a great thinker, but he had no respect to any existing laws. Basically he was the law and he could not allow anybody else to chanllenge him. He challenged and destroyed the traditional Chinese culture, good and bad. He gave woman the same right as man, but destroyed the traditional value of woman. This also made him very unrealistic, as he said in a poem, “Ten thousand years is too long, seize the day.” The Great Leap Forward (1958) is a direct result of such thinking. During the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), everything took a very long pause except constant class struggle and population growth. Inflation was zero and salary freezed for everyone. Education was badly damaged. Mao developed his fighting (or struggling) philosophy in his late years, as he said, “Fighting with heaven, fighting with earth, and fighting with human being, what a great pleasure!” China was isolated from the rest of the world and nobody knew the outside world at all.

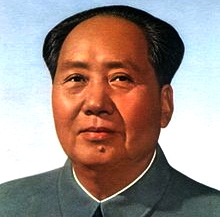

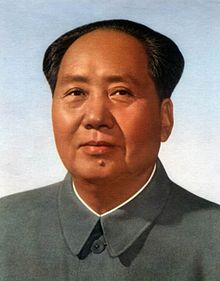

Official 1960–1966 portrait of Mao Zedong

Official 1960–1966 portrait of Mao Zedong

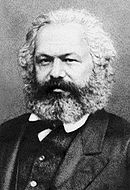

Mao Zedong, also transliterated as Mao Tse-tung ![]() listen (help·info), and commonly referred to as Chairman Mao (December 26, 1893 – September 9, 1976), was a Chinesecommunist revolutionary and a founding father of the People’s Republic of China, which he governed as Chairman of the Communist Party of China from its establishment in 1949 until his death. His Marxist-Leninist theories, military strategies and political policies are collectively known as Maoism.

listen (help·info), and commonly referred to as Chairman Mao (December 26, 1893 – September 9, 1976), was a Chinesecommunist revolutionary and a founding father of the People’s Republic of China, which he governed as Chairman of the Communist Party of China from its establishment in 1949 until his death. His Marxist-Leninist theories, military strategies and political policies are collectively known as Maoism.

Born the son of a wealthy farmer in Shaoshan, Hunan, Mao adopted a Chinese nationalistand anti-imperialist outlook in early life, particularly influenced by the events of the Xinhai Revolution of 1911 and May Fourth Movement of 1919. Mao converted to Marxism-Leninism while working at Peking University and became a founding member of theCommunist Party of China (CPC), leading the Autumn Harvest Uprising in 1927. During theChinese Civil War between the Kuomingtang (KMT) and the CPC, Mao helped to found theRed Army, led the Jiangxi Soviet‘s radical land policies ultimately became head the CPC during the Long March. Although the CPC temporarily allied with the KMT under the United Front during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45), after Japan’s defeat China’s civil war resumed and in 1949 Mao’s forces defeated the Nationalists who withdrew to Taiwan.

On October 1, 1949 Mao proclaimed the foundation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), a one-party socialist state controlled by the CPC. In the following years Mao solidified his control through land reforms and through a psychological victory in the Korean War, and through campaigns against landlords, people he termed “counterrevolutionaries“, and other perceived enemies of the state. In 1957 he launched a campaign known as the Great Leap Forward that aimed to rapidly transform China’s economy from an agrarian economy to an industrial one. This campaign, however, led to one the deadliest famines in history. In 1966, he initiated the Cultural Revolution, a program to weed out supposed counter-revolutionary elements in Chinese society that lasted 10 years and was marked by violent class struggle, widespread destruction of cultural artifacts and unprecedented elevation of Mao’s personality cult and which is officially regarded as a “severe setback” for the PRC. In 1972, he welcomed American president Richard Nixon in Beijing, signalling a policy of opening China.

A highly controversial figure, Mao is regarded as one of the most important individuals in modern world history. Mao is officially held in high regard in the People’s Republic of China. Supporters regard him as a great leader and credit him with numerous accomplishments including modernizing China and building it into a world power, promoting the status of women, improving education and health care, providing universal housing, and increasing life expectancy as China’s population grew from around 550 to over 900 million during the period of his leadership. Maoists furthermore promote his role as theorist, statesman, poet, and visionary. In contrast, critics, including many historians, have characterized him as a dictator who oversaw systematic human rights abuses, and whose rule is estimated to have contributed to the deaths of 40–70 million people through starvation, forced labor and executions, ranking his tenure as the top incidence of democide in human history.

Early life of Mao Zedong – Youth and the Xinhai Revolution: 1893–1911

Mao was born on December 26, 1893 in Shaoshan village, Shaoshan, Hunan. His father, Mao Yichang, was an impoverished peasant who had become one of the wealthiest farmers in Shaoshan. Zedong described his father as a stern disciplinarian, who would beat him and his three siblings, the boys Zemin and Zetan, and an adopted girl, Zejian. Yichang’s wife, Wen Qimei, was a devout Buddhist who tried to temper her husband’s strict attitude. Zedong too became a Buddhist, but abandoned this faith in his mid-teenage years. Aged 8, Mao was sent to Shaoshan Primary School. Learning the value systems of Confucianism, he later admitted that he didn’t enjoy the classical Chinese texts preaching Confucian morals, instead favouring popular novels like Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Water Margin. Aged 13, Mao finished primary education, and his father had him married to the 17-year-old Luo Yigu, uniting their land-owning families. Mao refused to recognise her as his wife, becoming a fierce critic of arranged marriage and temporarily moving away. Luo was locally disgraced and died in 1910.

Mao’s childhood home in Shaoshan, in 2010, by which time it had become a tourist destination.

Mao’s childhood home in Shaoshan, in 2010, by which time it had become a tourist destination.

Working on his father’s farm, Mao read voraciously, developing a “political consciousness” from Zheng Guanying‘s booklet which lamented the deterioration of Chinese power and argued for the adoption of representative democracy. Interested in history, Mao was inspired by the military prowess and nationalistic fervour of George Washington and Napoleon Bonaparte. His political views were shaped by Gelaohui-led protests which erupted following a famine in Hunanese capital Changsha; Mao supported the protester’s demands, but the armed forces suppressed the dissenters and executed their leaders. The famine spread to Shaoshan, where starving peasants seized his father’s grain; disapproving of their actions as morally wrong, Mao nevertheless claimed sympathy for their situation. Aged 16, Mao moved to a higher primary school in nearby Dongshan, where he was bullied for his peasant background.

In 1911, Mao began middle school in Changsha. Revolutionary sentiment was strong in the city, with widespread animosity towards Emperor Puyi‘s absolute monarchy and many advocating republicanism. The republicans’ figurehead was Sun Yat-sen, an American-educated Christian who led the Tongmenghui society. In Changsha, Mao was influenced by Sun’s newspaper, The People’s Independence (Minli bao), and called for Sun to become president in a school essay. As a symbol of rebellion against the Manchumonarch, Mao and a friend cut off their queue pigtails, a sign of subservience to the emperor.

Inspired by Sun’s republicanism, the army rose up across southern China, sparking the Xinhai Revolution. Changsha’s governor fled, leaving the city in republican control. Supporting the revolution, Mao joined the rebel army as a private soldier, but was not involved in fighting. The northern provinces remained loyal to the emperor, and hoping to avoid a civil war, Sun—proclaimed “provisional president” by his supporters—compromised with the monarchist general Yuan Shikai. The monarchy would be abolished, creating theRepublic of China, but the monarchist Yuan would become president. The revolution over, Mao resigned from the army in 1912, after six months of being a soldier. Around this time, Mao discovered socialism from a newspaper article; proceeding to read pamphlets byJiang Kanghu, the student founder of the Chinese Socialist Party, Mao remained interested yet unconvinced by the idea.

Fourth Normal School of Changsha: 1912–19

Mao enrolled and dropped out of a police academy, a soap-production school, a law school, an economics school, and the government-run Changsha Middle School. Studying independently, he spent much time in Changsha’s library, reading core works of classical liberalism such as Adam Smith‘s The Wealth of Nations and Montesquieu‘s The Spirit of the Laws, as well as the works of western scientists and philosophers such as Darwin, Mill, Rousseau, and Spencer. Viewing himself as an intellectual, years later he admitted that at this time he thought himself better than working people. Inspired by Friedrich Paulsen, the liberal emphasis on individualism led Mao to believe that strong individuals were not bound by moral codes but should strive for the greater good; that the end justifies the means. Seeing no use in his son’s intellectual pursuits, Mao’s father cut off his allowance, forcing him to move into a hostel for the destitute.

Desiring to become a teacher, Mao enrolled at the Fourth Normal School of Changsha, which soon merged with the First Normal School of Changsha, widely seen as the best school in Hunan. Befriending Mao, professor Yang Changji urged him to read a radical newspaper, New Youth (Xin qingnian), the creation of his friend Chen Duxiu, a dean at Peking University. Although a Chinese nationalist, Chen argued that China must look to the west to cleanse itself of superstition and autocracy. Mao published his first article in New Youth in April 1917, instructing readers to increase their physical strength to serve the revolution. He joined the Society for the Study of Wang Fuzhi (Chuan-shan Hsüeh-she), a revolutionary group founded by Changsha literati who wished to emulate the philosopher Wang Fuzhi.

In his first school year, Mao befriended an older student, Xiao Yu; together they went on a walking tour of Hunan, begging and writing literary couplets to obtain food. A popular student, in 1915 Mao was elected secretary of the Students Society. Forging an Association for Student Self-Government, he led protests against school rules. In spring 1917, he was elected to command the students’ volunteer army, set up to defend the school from marauding soldiers. Increasingly interested in the techniques of war, he took a keen interest in World War I, and also began to develop a sense of solidarity with workers. Mao undertook feats of physical endurance with Xiao Yu and Cai Hesen, and with other young revolutionaries they formed the Renovation of the People Study Society in April 1918 to debate Chen Duxiu’s ideas. Desiring personal and societal transformation, the Society gained 70–80 members, many of whom would later join the Communist Party. Mao graduated in June 1919, being ranked third in the year.

Early revolutionary Activity of Mao Zedong

Beijing, Anarchism, and Marxism: 1917–19

Mao moved to Beijing, where his mentor Yang Changji had taken a job at Peking University. Yang thought Mao exceptionally “intelligent and handsome,” securing him a job as assistant to the university librarian Li Dazhao, an early Chinese communist. Li authored a series of New Youth articles on the October Revolution in Russia, during which the communist Bolshevik Party under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin had seized power. Lenin was an advocate of the socio-political theory of Marxism, first developed by the German sociologists Karl Marxand Friedrich Engels, and Li’s articles brought an understanding of Marxism to the Chinese revolutionary movement. Becoming “more and more radical”, Mao was influenced by Peter Kropotkin‘s anarchism but joined Li’s Study Group and “developed rapidly toward Marxism” during the winter of 1919.

Paid a low wage, Mao lived in a cramped room with seven other Hunanese students, but believed that Beijing’s beauty offered “vivid and living compensation.” At the university, Mao was widely snubbed due to his rural accent and lowly position. By joining the university’s Philosophy and Journalism Societies, he attended lectures and seminars by the likes of Chen Duxiu, Hu Shi, and Qian Xuantong. Mao’s time in Beijing ended in the spring of 1919, when he travelled to Shanghai with friends departing for France, before returning to Shaoshan, where his mother was terminally ill; she died in October 1919, with her husband dying in January 1920.

Student rebellions: 1919–20

China had fallen victim to the expansionist policies of the Empire of Japan, who had conquered large areas of Chinese-controlled territory with the support of France, the UK and the US at the Treaty of Versailles. Under the control of the warlord Duan Qirui, the Chinese Beiyang Government had accepted Japanese dominance, agreeing to their Twenty-One Demands despite popular opposition. In May 1919, the May Fourth Movement erupted in Beijing, with Chinese patriots rallying against the Japanese and Duan’s government. Duan’s troops were sent in to crush the protests, but unrest spread throughout China. In Changsha, Mao had gained employment teaching history at the Xiuye Primary School. He began organizing protests against the pro-Duan Governor of Hunan Province, Zhang Jinghui, popularly known as “Zhang the Venomous” due to his criminal activities. In late May, Mao co-founded the Hunanese Student Association with He Shuheng and Deng Zhongxia, organizing a student strike for June and in July 1919 began production of a weekly radical magazine, Xiang River Review (Xiangjiang pinglun). Using vernacular language that would be understandable to the majority of China’s populace, he advocated the need for a “Great Union of the Popular Masses”, strengthened trade unions able to wage non-violent revolution; his ideas were not Marxist, but heavily influenced by Kropotkin’s concept of mutual aid.

Students in Beijing rallied during the May Fourth Movement.

Students in Beijing rallied during the May Fourth Movement.

Zhang banned the Student Association, but Mao continued publishing after assuming editorship of liberal magazine New Hunan (Xin Hunan) and offering articles in popular local newspaperJustice (Ta Kung Po). Several of these articles advocated feminist views, calling for the liberation of women in Chinese society; Mao was influenced by his forced arranged-marriage. In December 1919, Mao helped organise a general strike in Hunan, securing some concessions, but Mao and other student leaders felt threatened by Zhang, and Mao returned to Beijing, visiting the terminally ill Yang Changji. Mao found that his articles had achieved a level of fame among the revolutionary movement, and set about soliciting support in overthrowing Zhang. Coming across newly translated Marxist literature by Thomas Kirkup, Karl Kautsky, and Marx and Engels—notably The Communist Manifesto—he came under their increasing influence, but was still eclectic in his views.

Mao visited Tianjin, Jinan, and Qufu, before moving to Shanghai, where he worked as a laundryman and met Chen Duxiu, noting that Chen’s adoption of Marxism “deeply impressed me at what was probably a critical period in my life”. In Shanghai, Mao met an old teacher of his, Yi Peiji, a revolutionary and member of the Kuomintang (KMT), or Chinese Nationalist Party, which was gaining increasing support and influence. Yi introduced Mao to General Tan Yankai, a senior KMT member who held the loyalty of troops stationed along the Hunanese border with Guangdong. Tan was plotting to overthrow Zhang, and Mao aided him by organizing the Changsha students. In June 1920, Tan led his troops into Changsha, while Zhang fled. In the subsequent reorganization of the provincial administration, Mao was appointed headmaster of the junior section of the First Normal School. Now receiving a large income, he married Yang Kaihui in the winter of 1920.

Founding the Communist Party of China: 1921–22

Location of the first Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in July 1921, in Xintiandi, former French Concession, Shanghai.

The Communist Party of China was founded by Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao in the French concession of Shanghai in 1921 as a study society and informal network. Mao set up a Changsha branch, also establishing a branch of the Socialist Youth Corps. Opening a bookstore under the control of his new Cultural Book Society, its purpose was to propagate revolutionary literature throughout Hunan. Helping to organise workers’ strikes in the winter of 1920–21, he was involved in the movement for Hunan autonomy, hoping that a Hunanese constitution would increase civil liberties in the province, making his revolutionary activity easier; although the movement was successful, in later life, he denied any involvement. By 1921, small Marxist groups existed in Shanghai, Beijing, Changsha, Wuhan, Canton and Jinan, and it was decided to hold a central meeting, which began in Shanghai on July 23, 1921. The first session of the National Congress of the Communist Party of China was attended by 13 delegates, Mao included, and met in a girls’ school that was closed for the summer. After the authorities sent a police spy to the congress, the delegates moved to a boat on South Lake near Chiahsing to escape detection. Although Soviet and Comintern delegates attended, the first congress ignored Lenin’s advice to accept a temporary alliance between the communists and the “bourgeois democrats” who also advocated national revolution; instead they stuck to the orthodox Marxist belief that only the urban proletariat could lead a socialist revolution.

Now party secretary for Hunan, Mao was stationed in Changsha, from which he went on a Communist recruitment drive. In August 1921, he founded the Self-Study University, through which readers could gain access to revolutionary literature, housed in the premises of the Society for the Study of Wang Fuzhi. Taking part in the YMCA mass education movement to fight illiteracy, he opened a Changsha branch, though replaced the usual textbooks with revolutionary tracts in order to spread Marxism among the students. He continued organizing the labour movement to strike against the administration of Hunan Governor Zhao Hengti, particularly following the execution of two anarchists. In July 1922, the Second Congress of the Communist Party took place in Shanghai, though Mao lost the address and couldn’t attend. Adopting Lenin’s advice, the delegates agreed to an alliance with the “bourgeois democrats” of the KMT for the good of the “national revolution”. Communist Party members joined the KMT, hoping to push its politics leftward. Mao enthusiastically agreed with this decision, arguing for an alliance across China’s socio-economic classes; a vocal anti-imperialist, in his writings he lambasted the governments of Japan, UK and US, describing the latter as “the most murderous of hangmen.” Mao’s strategy for the successful and famous Anyuan coal mines strikes (contrary to later Party historians) depended on both “proletarian” and “bourgeois” strategies. The success depended on innovative organizing by Liu Shaoqi and Li Lisan who not only mobilised the miners, but formed schools and cooperatives. They also engaged local intellectuals, gentry, military officers, merchants, Red Gang dragon heads and church clergy in support.

Collaboration with the Kuomintang: 1922–27

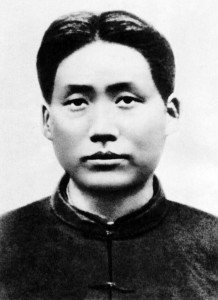

Mao the Revolutionary in 1927.

Mao the Revolutionary in 1927.

At the Third Congress of the Communist Party in Shanghai in June 1923, the delegates reaffirmed their commitment to working with the KMT against the Beiyang government and imperialists. Supporting this position, Mao was elected to the Party Committee, taking up residence in Shanghai. Attending the First KMT Congress, held in Guangzhou in early 1924, Mao was elected an alternate member of the KMT Central Executive Committee, and put forward four resolutions to decentralise power to urban and rural bureaus. His enthusiastic support for the KMT earned him the suspicion of some communists. In late 1924, Mao returned to Shaoshan to recuperate from an illness. Discovering that the peasantry were increasingly restless due to the upheaval of the past decade, some had seized land from wealthy landowners to found communes; this convinced him of the revolutionary potential of the peasantry, an idea advocated by the KMT but not the communists. As a result, he was appointed to run the KMT’s Peasant Movement Training Institute, also becoming Director of its Propaganda Department and editing its Political Weekly (Zhengzhi zhoubao) newsletter. Through the Peasant Movement Training Institute, Mao took an active role in organizing the revolutionary Hunanese peasants and preparing them for militant activity, taking them through military training exercises and getting them to study various left-wing texts. In the winter of 1925, Mao fled to Canton after his revolutionary activities attracted the attention of Zhao’s regional authorities.