Lawyer

Scopes Monkey Trial Overview Clrarence Darrow versus Bryant

Scopes Monkey Trial Overview Clarence Darrow versus Bryant.

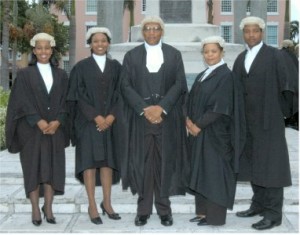

Margaret Battye (1909–1949), Australian lawyer, in her court dress.

Margaret Battye (1909–1949), Australian lawyer, in her court dress.

A lawyer, according to Black’s Law Dictionary, is “a person learned in the law; as anattorney, counsel or solicitor; a person who is practicing law.” Law is the system of rules of conduct established by the sovereign government of a society to correct wrongs, maintain the stability of political and social authority, and deliver justice. Working as a lawyer involves the practical application of abstract legal theories and knowledge to solve specific individualized problems, or to advance the interests of those who retain (i.e., hire) lawyers to perform legal services.

The role of the lawyer varies significantly across legal jurisdictions, and so it can be treated here in only the most general terms.

Terminology

In practice, legal jurisdictions exercise their right to determine who is recognized as being a lawyer. As a result, the meaning of the term “lawyer” may vary from place to place.

- In Australia, the word “lawyer” is used to refer to both barristers and solicitors (whether in private practice or practising as corporate in-house counsel).

- In Canada, the word “lawyer” only refers to individuals who have been called to the bar or, in Quebec, have qualified as civil law notaries. Common law lawyers in Canada are formally and properly called “barristers and solicitors”, but should not be referred to as “attorneys”, since that term has a different meaning in Canadian usage. However, in Quebec, civil law advocates (or avocats in French) often call themselves “attorney” and sometimes “barrister and solicitor” in English.

- In England and Wales, “lawyer” is used to refer to persons who provide reserved legal activities and includes practitioners such as barristers, solicitors, registered foreign lawyers, patent attorneys, trade mark attorneys, licensed conveyancers, commissioners for oaths,immigration advisers and claims management services [Legal Services Act 2007] as well as people who are involved with the law but do not practise it on behalf of individual clients, such as judges, court clerks, and drafters of legislation.

- In India, the term “lawyer” is often colloquially used, but the official term is “advocate” as prescribed under the Advocates Act, 1961.

- In Scotland, the word “lawyer” refers to a more specific group of legally trained people. It specifically includes advocates andsolicitors. In a generic sense, it may also include judges and law-trained support staff.

- In the United States, the term generally refers to attorneys who may practice law. It is never used to refer to patent agents or paralegals.

- Other nations tend to have comparable terms for the analogous concept.

Responsibilities

In most countries, particularly civil law countries, there has been a tradition of giving many legal tasks to a variety of civil law notaries, clerks, and scriveners. These countries do not have “lawyers” in the American sense, insofar as that term refers to a single type of general-purpose legal services provider; rather, their legal professions consist of a large number of different kinds of law-trained persons, known as jurists, of which only some are advocates who are licensed to practice in the courts. It is difficult to formulate accurate generalizations that cover all the countries with multiple legal professions, because each country has traditionally had its own peculiar method of dividing up legal work among all its different types of legal professionals.

In most countries, particularly civil law countries, there has been a tradition of giving many legal tasks to a variety of civil law notaries, clerks, and scriveners. These countries do not have “lawyers” in the American sense, insofar as that term refers to a single type of general-purpose legal services provider; rather, their legal professions consist of a large number of different kinds of law-trained persons, known as jurists, of which only some are advocates who are licensed to practice in the courts. It is difficult to formulate accurate generalizations that cover all the countries with multiple legal professions, because each country has traditionally had its own peculiar method of dividing up legal work among all its different types of legal professionals.

Notably, England, the mother of the common law jurisdictions, emerged from the Dark Ages with similar complexity in its legal professions, but then evolved by the 19th century to a single dichotomy between barristers and solicitors. An equivalent dichotomy developed between advocates and procurators in some civil law countries, though these two types did not always monopolize the practice of law as much as barristers and solicitors, in that they always coexisted with civil law notaries.

Several countries that originally had two or more legal professions have since fused or united their professions into a single type of lawyer. Most countries in this category are common law countries, though France, a civil law country, merged its jurists in 1990 and 1991 in response to Anglo-American competition. In countries with fused professions, a lawyer is usually permitted to carry out all or nearly all the responsibilities listed below.

In most countries, particularly civil law countries, there has been a tradition of giving many legal tasks to a variety of civil law notaries, clerks, and scriveners. These countries do not have “lawyers” in the American sense, insofar as that term refers to a single type of general-purpose legal services provider; rather, their legal professions consist of a large number of different kinds of law-trained persons, known as jurists, of which only some are advocates who are licensed to practice in the courts. It is difficult to formulate accurate generalizations that cover all the countries with multiple legal professions, because each country has traditionally had its own peculiar method of dividing up legal work among all its different types of legal professionals.

Notably, England, the mother of the common law jurisdictions, emerged from the Dark Ages with similar complexity in its legal professions, but then evolved by the 19th century to a single dichotomy between barristers and solicitors. An equivalent dichotomy developed between advocates and procurators in some civil law countries, though these two types did not always monopolize the practice of law as much as barristers and solicitors, in that they always coexisted with civil law notaries.

Notably, England, the mother of the common law jurisdictions, emerged from the Dark Ages with similar complexity in its legal professions, but then evolved by the 19th century to a single dichotomy between barristers and solicitors. An equivalent dichotomy developed between advocates and procurators in some civil law countries, though these two types did not always monopolize the practice of law as much as barristers and solicitors, in that they always coexisted with civil law notaries.

Several countries that originally had two or more legal professions have since fused or united their professions into a single type of lawyer. Most countries in this category are common law countries, though France, a civil law country, merged its jurists in 1990 and 1991 in response to Anglo-American competition. In countries with fused professions, a lawyer is usually permitted to carry out all or nearly all the responsibilities listed below.

Oral Argument In The Courts

Arguing a client’s case before a judge or jury in a court of law is the traditional province of the barrister in England, and of advocates in some civil law jurisdictions. However, the boundary between barristers and solicitors has evolved. In England today, the barrister monopoly covers only appellate courts, and barristers must compete directly with solicitors in many trial courts. In countries like the United States that have fused legal professions, there are trial lawyers who specialize in trying cases in court, but trial lawyers do not have a de jure monopoly like barristers. In some countries, litigants have the option of arguing pro se, or on their own behalf. It is common for litigants to appear unrepresented before certain courts like small claims courts; indeed, many such courts do not allow lawyers to speak for their clients, in an effort to save money for all participants in a small case. In other countries, like Venezuela, no one may appear before a judge unless represented by a lawyer. The advantage of the latter regime is that lawyers are familiar with the court’s customs and procedures, and make the legal system more efficient for all involved. Unrepresented parties often damage their own credibility or slow the court down as a result of their inexperience.

Research And Drafting Of Court Papers

Often, lawyers brief a court in writing on the issues in a case before the issues can be orally argued. They may have to perform extensive research into relevant facts and law while drafting legal papers and preparing for oral argument.

Often, lawyers brief a court in writing on the issues in a case before the issues can be orally argued. They may have to perform extensive research into relevant facts and law while drafting legal papers and preparing for oral argument.

In England, the usual division of labour is that a solicitor will obtain the facts of the case from the client and then brief a barrister (usually in writing). The barrister then researches and drafts the necessary court pleadings (which will be filed and served by the solicitor) and orally argues the case.

In Spain, the procurator merely signs and presents the papers to the court, but it is the advocate who drafts the papers and argues the case.

In some countries, like Japan, a scrivener or clerk may fill out court forms and draft simple papers for lay persons who cannot afford or do not need attorneys, and advise them on how to manage and argue their own cases.

Advocacy (written and oral) In Administrative Hearings

In most developed countries, the legislature has granted original jurisdiction over highly technical matters to executive branch administrative agencies which oversee such things. As a result, some lawyers have become specialists in administrative law. In a few countries, there is a special category of jurists with a monopoly over this form of advocacy; for example, France formerly hadconseils juridiques (who were merged into the main legal profession in 1991). In other countries, like the United States, lawyers have been effectively barred by statute from certain types of administrative hearings in order to preserve their informality.

Client Intake and Counseling (with regard to pending litigation)

An important aspect of a lawyer’s job is developing and managing relationships with clients (or the client’s employees, if the lawyer works in-house for a government or corporation). The client-lawyer relationship often begins with an intake interview where the lawyer gets to know the client personally, discovers the facts of the client’s case, clarifies what the client wants to accomplish, shapes the client’s expectations as to what actually can be accomplished, begins to develop various claims or defenses, and explains her or his fees to the client.

In England, only solicitors were traditionally in direct contact with the client. The solicitor retained a barrister if one was necessary and acted as an intermediary between the barrister and the client. In most cases barristers were obliged, under what is known as the “cab rank rule”, to accept instructions for a case in an area in which they held themselves out as practising, at a court at which they normally appeared and at their usual rates.

Legal advice is the application of abstract principles of law to the concrete facts of the client’s case in order to advise the client about what they should do next. In many countries, only a properly licensed lawyer may provide legal advice to clients for good consideration, even if no lawsuit is contemplated or is in progress. Therefore, even conveyancers and corporate in-house counsel must first get a license to practice, though they may actually spend very little of their careers in court. Failure to obey such a rule is the crime of unauthorized practice of law.

Legal advice is the application of abstract principles of law to the concrete facts of the client’s case in order to advise the client about what they should do next. In many countries, only a properly licensed lawyer may provide legal advice to clients for good consideration, even if no lawsuit is contemplated or is in progress. Therefore, even conveyancers and corporate in-house counsel must first get a license to practice, though they may actually spend very little of their careers in court. Failure to obey such a rule is the crime of unauthorized practice of law.

In other countries, jurists who hold law degrees are allowed to provide legal advice to individuals or to corporations, and it is irrelevant if they lack a license and cannot appear in court. Some countries go further; in England and Wales, there is nogeneral prohibition on the giving of legal advice. Sometimes civil law notaries are allowed to give legal advice, as in Belgium. In many countries, non-jurist accountants may provide what is technically legal advice in tax and accounting matters.

History of the Legal Profession

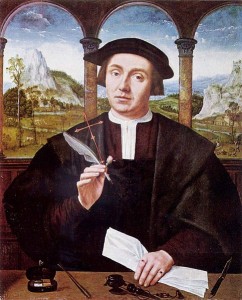

16th-century painting of a civil law notary, by Flemish painter Quentin Massys. A civil law notary is roughly analogous to a common law solicitor, except that, unlike solicitors, civil law notaries do not practice litigation to any degree.

16th-century painting of a civil law notary, by Flemish painter Quentin Massys. A civil law notary is roughly analogous to a common law solicitor, except that, unlike solicitors, civil law notaries do not practice litigation to any degree.

Ancient Greece

The earliest people who could be described as “lawyers” were probably the orators of ancient Athens (see History of Athens). However, Athenian orators faced serious structural obstacles. First, there was a rule that individuals were supposed to plead their own cases, which was soon bypassed by the increasing tendency of individuals to ask a “friend” for assistance. However, around the middle of the fourth century, the Athenians disposed of the perfunctory request for a friend. Second, a more serious obstacle, which the Athenian orators never completely overcame, was the rule that no one could take a fee to plead the cause of another. This law was widely disregarded in practice, but was never abolished, which meant that orators could never present themselves as legal professionals or experts. They had to uphold the legal fiction that they were merely an ordinary citizen generously helping out a friend for free, and thus they could never organize into a real profession—with professional associations and titles and all the other pomp and circumstance—like their modern counterparts. Therefore, if one narrows the definition to those men who could practice the legal profession openly and legally, then the first lawyers would have to be the orators of ancient Rome.

Early Ancient Rome

A law enacted in 204 BC barred Roman advocates from taking fees, but the law was widely ignored. The ban on fees was abolished by Emperor Claudius, who legalized advocacy as a profession and allowed the Roman advocates to become the first lawyers who could practice openly—but he also imposed a fee ceiling of 10,000 sesterces. This was apparently not much money; the Satires of Juvenal complain that there was no money in working as an advocate.

Like their Greek contemporaries, early Roman advocates were trained in rhetoric, not law, and the judges before whom they argued were also not law-trained. But very early on, unlike Athens, Rome developed a class of specialists who were learned in the law, known as jurisconsults (iuris consulti). Jurisconsults were wealthy amateurs who dabbled in law as an intellectual hobby; they did not make their primary living from it. They gave legal opinions (responsa) on legal issues to all comers (a practice known as publice respondere). Roman judges and governors would routinely consult with an advisory panel of jurisconsults before rendering a decision, and advocates and ordinary people also went to jurisconsults for legal opinions. Thus, the Romans were the first to have a class of people who spent their days thinking about legal problems, and this is why their law became so “precise, detailed, and technical.”

Late Ancient Rome

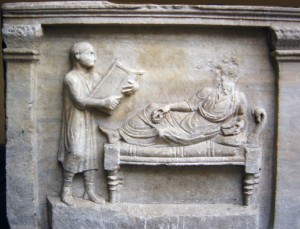

Detail from the sarcophagus of Roman lawyer Valerius Petronianus 315-320 AD. Picture by Giovanni Dall’Orto.

Detail from the sarcophagus of Roman lawyer Valerius Petronianus 315-320 AD. Picture by Giovanni Dall’Orto.

During the Roman Republic and the early Roman Empire, jurisconsults and advocates were unregulated, since the former were amateurs and the latter were technically illegal. Any citizen could call himself an advocate or a legal expert, though whether people believed him would depend upon his personal reputation. This changed once Claudius legalized the legal profession. By the start of the Byzantine Empire, the legal profession had become well-established, heavily regulated, and highly stratified. The centralization and bureaucratization of the profession was apparently gradual at first, but accelerated during the reign of Emperor Hadrian. At the same time, the jurisconsults went into decline during the imperial period.

In the words of Fritz Schulz, “by the fourth century things had changed in the eastern Empire: advocates now were really lawyers.” For example, by the fourth century, advocates had to be enrolled on the bar of a court to argue before it, they could only be attached to one court at a time, and there were restrictions (which came and went depending upon who was emperor) on how many advocates could be enrolled at a particular court. By the 380s, advocates were studying law in addition to rhetoric (thus reducing the need for a separate class of jurisconsults); in 460, Emperor Leo imposed a requirement that new advocates seeking admission had to produce testimonials from their teachers; and by the sixth century, a regular course of legal study lasting about four years was required for admission. Claudius’s fee ceiling lasted all the way into the Byzantine period, though by then it was measured at 100 solidi. Of course, it was widely evaded, either through demands for maintenance and expenses or a sub rosa barter transaction. The latter was cause for disbarment.

The notaries (tabelliones) appeared in the late Roman Empire. Like their modern-day descendants, the civil law notaries, they were responsible for drafting wills, conveyances, and contracts. They were ubiquitous and most villages had one. In Roman times, notaries were widely considered to be inferior to advocates and jury consults.<rnes, 515″/> Roman notaries were not law-trained; they were barely literate hacks who wrapped the simplest transactions in mountains of legal jargon, since they were paid by the line.

Middle Ages

The Village Lawyer, c. 1621, by Pieter Brueghel the Younger

The Village Lawyer, c. 1621, by Pieter Brueghel the Younger

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the onset of the Early Middle Ages, the legal profession of Western Europe collapsed. As James Brundage has explained: “[by 1140], no one in Western Europe could properly be described as a professional lawyer or a professional canonist in anything like the modern sense of the term ‘professional.’ ” However, from 1150 onward, a small but increasing number of men became experts in canon law but only in furtherance of other occupational goals, such as serving the Roman Catholic Church as priests. From 1190 to 1230, however, there was a crucial shift in which some men began to practice canon law as a lifelong profession in itself.

The legal profession’s return was marked by the renewed efforts of church and state to regulate it. In 1231 two French councils mandated that lawyers had to swear an oath of admission before practicing before the bishop’s courts in their regions, and a similar oath was promulgated by the papal legate in London in 1237. During the same decade, Frederick II, the emperor of the Kingdom of Sicily, imposed a similar oath in his civil courts. By 1250 the nucleus of a new legal profession had clearly formed. The new trend towards professionalization culminated in a controversial proposal at the Second Council of Lyon in 1275 that all ecclesiastical courts should require an oath of admission. Although not adopted by the council, it was highly influential in many such courts throughout Europe. The civil courts in England also joined the trend towards professionalization; in 1275 a statute was enacted that prescribed punishment for professional lawyers guilty of deceit, and in 1280 the mayor’s court of the city of London promulgated regulations concerning admission procedures, including the administering of an oath. And in 1345, the French crown promulgated a royal ordinance which set forth 24 rules governing advocates, of which 12 were integrated into the oath to be taken by them.

The French medieval oaths were widely influential and of enduring importance; for example, they directly influenced the structure of the advocates’ oath adopted by the Canton of Geneva in 1816. In turn, the 1816 Geneva oath served as the inspiration for the attorney’s oath drafted by David Dudley Field as Section 511 of the proposed New York Code of Civil Procedure of 1848, which was the first attempt in the United States at a comprehensive statement of a lawyer’s professional duties.

Titles

Generally speaking, the modern practice is for lawyers to avoid use of any title, although formal practice varies across the world.

Generally speaking, the modern practice is for lawyers to avoid use of any title, although formal practice varies across the world.

Historically lawyers in most European countries were addressed with the title of doctor, and countries outside of Europe have generally followed the practice of the European country which had policy influence through colonization. The first university degrees, starting with the law school of the University of Bologna (or glossators) in the 11th century, were all law degrees and doctorates. Degrees in other fields did not start until the 13th century, but the doctor continued to be the only degree offered at many of the old universities until the 20th century. Therefore, in many of the southern European countries, including Portugal and Italy, lawyers have traditionally been addressed as “doctor,” a practice which was transferred to many countries in South America and Macau. The term “doctor” has since fallen into disuse, although it is still a legal title in Italy and in use in many countries outside of Europe.

In French– (France, Quebec, Belgium, Luxembourg) and Dutch-speaking countries (Netherlands, Belgium), legal professional are addressed as Maître …, abbreviated to Me … (in French) or Meester …, abbreviated to mr. … (in Dutch).

The title of doctor has never been used to address lawyers in England or other common law countries (with the exception of the United States). This is because until 1846 lawyers in England were not required to have a university degree and were trained by other attorneys by apprenticeship or in the Inns of Court. Since law degrees started to become a requirement for lawyers in England, the degree awarded has been the undergraduate LL.B. In South Africa holders of a law degree who have completed a year of pupillage and have been admitted to the bar may use the title “Advocate”, abbreviated to “Adv” in written correspondence.Likewise, Italian law graduates who have qualified for the bar use the title “Avvocato”, abbreviated in “Avv.”

Even though most lawyers in the United States do not use any titles, the law degree in that country is the Juris Doctor, a professional doctorate degree, and some J.D. holders in the United States use the title of “Doctor” in professional and academic situations.

In countries where holders of the first law degree traditionally use the title of doctor (e.g. Peru, Brazil, Macau, Portugal, Argentina), J.D. holders who are attorneys will often use the title of doctor as well. It is common for English-language male lawyers to use the honorific suffix “Esq.” (for “Esquire“). In the United States the style is also used by female lawyers.

In many Asian countries, holders of the Juris Doctor degree are also called “博士” (doctor).