Kansas

Kansas City History – Part- 1

The city’s initial growth in the 1850s and George Kessler’s vision of boulevards and fountains are covered in the clip from “KC150”, a KMBC 9 News Special celebrating Kansas City’s sesquicentennial in 2000.

Kansas City History – Part- 2

18th and Vine jazz history, Charlie “Bird” Parker and the Tom Pendergast era are covered in this clip from “KC150”, a KMBC 9 News Special celebrating Kansas City’s sesquicentennial in 2000.

- (1541) Explorers, searching for gold, claimed Kansas for Spain

1600’s

1800’s

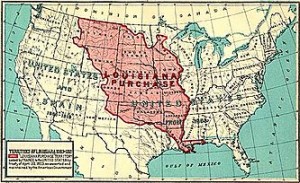

- (1803) U.S. acquired most of Kansas from France in the Louisiana Purchase

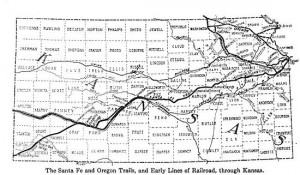

- (1822) Captain W. H. Becknell pioneered the Santa Fe Trail

- (1827) Fort Leavenworth established

- (1830’s) Settlers arrived by the thousands

(1854) Kansas Territory was organized

(1854) Kansas Territory was organized- (1855-1859) The Kansas-Nebraska Act caused bloody fighting over slavery; Kansas was called “Bloody Kansas.”

- (1860) First railroad reached Kansas

- (1862) Kansas became a state

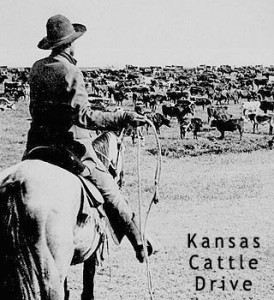

- (1867) The railroad arrived in Abilene, and the first cattle were driven up the Chisholm Trail

- (1887) Susanna Salter elected mayor of Argonia, Kansas; became the first woman mayor in the country

- (1894-1895) The state’s oil and gas fields went into production

Frank Bond’s illustration of the Louisiana Purchase.

The history of Kansas, argued historian Carl L. Becker a century ago, reflects American ideals. He wrote: “The Kansas spirit is the American spirit double distilled. It is a new grafted product of American individualism, American idealism, American intolerance. Kansas is America in microcosm.”

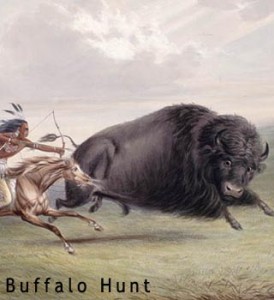

Located on the eastern edge of the Great Plains, the U.S. state of Kansas was the home of nomadic Native American tribes who hunted the vast herds of bison. The region first appears in western history in the 16th century at the time of the Spanish conquest of Mexico, when Spanish conquistadores explored the unknown land now known as Kansas. It was later explored by French fur trappers who traded with the Native Americans. Most of Kansas became permanently part of the United States in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. The southwest portion had a different history of association with Spanish, Mexican and the Republic of Texas rule before the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848. In the 19th century, the first American explorers designated the area as the “Great American Desert.”

When the area was opened to Euro-American settlement in the 1850s, Kansas became the first battlefield in what a few years later became the American Civil War, as settlers fought over whether the territory would be admitted as a free or slave state. After the war, Kansas was home to Wild West towns servicing the cattle trade. With the railroads came heavy immigration from the East, from Europe, and from Freedmen called “Exodusters“. For much of its history, Kansas has had a rural economy based on wheat and other crops, supplemented by oil and railroads. Since 1945 the farm population has sharply declined and manufacturing has become more important, typified by the aircraft industry of Wichita.

When the area was opened to Euro-American settlement in the 1850s, Kansas became the first battlefield in what a few years later became the American Civil War, as settlers fought over whether the territory would be admitted as a free or slave state. After the war, Kansas was home to Wild West towns servicing the cattle trade. With the railroads came heavy immigration from the East, from Europe, and from Freedmen called “Exodusters“. For much of its history, Kansas has had a rural economy based on wheat and other crops, supplemented by oil and railroads. Since 1945 the farm population has sharply declined and manufacturing has become more important, typified by the aircraft industry of Wichita.

Prehistory – The Paleo-Indians and Archaic peoples

According to the best archaeological and geological evidence available, Paleolithic, mammoth-hunting families moved into northwestern North America from northeast Asia sometime around the end of the Paleolithic (and, some believe, as late as 10,000 BC) by various means. Around 7000 BC, these immigrants entered into North America reaching Kansas. Once in Kansas, the indigenous ancestors never abandoned Kansas. They were later augmented by other indigenous peoples migrating from other parts of the continent. These bands of newcomers encountered mammoths, camels, ground sloths, and horses. The sophisticated big-game hunters did not keep a balance, resulting in the “Pleistocene overkill”, the rapid and systematic decimation of nearly all the species of large ice-age mammals in North America by 8000 BC. The hunters who pursued the mammoths may have represented the first of north Great Plains cycles of boom and bust, relentlessly exploiting the resource until it has been depleted or destroyed.

After the disappearance of big-game hunters, some archaic groups survived by becoming generalists rather than specialists, foraging in seasonal movements across the plains. The groups did not abandon hunting altogether, but also consumed wild plant foods and small game. Their tools became more varied, with grinding and chopping implements becoming more common, a sign that seeds, fruits, and greens constituted a greater proportion of their diet. Also, pottery-making societies emerged.

Introduction of agriculture

For most of the Archaic period, people did not transform their natural environment in any fundamental way. The groups outside the region, particularly in Mesoamerica, introduced major innovations, such as maize cultivation. Other groups in North American independently developed maize cultivation as well. Some archaic groups transferred from food gatherers to food producers around 3,000 years ago. They also possessed many of the cultural features that accompany semi-sedentary agricultural life: storage facilities, more permanent dwellings, larger settlements, and cemeteries or burial grounds. El Quartelejo was the northern most Indian pueblo. This settlement is the only pueblo in Kansas from which archaeological evidence has been recovered.

Despite the early advent of farming, late Archaic groups still exercised little control over their natural environment. Wild food resources remained important components of their diet even after the invention of pottery and the development of irrigation. The introduction of agriculture never resulted in the complete abandonment of hunting and foraging, even in the largest of Archaic societies.

European visitation and local tribes

European visitation and local tribes

In 1541, Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, the Spanish conquistador, visited Kansas, allegedly turning back near “Coronado Heights” in present-day Lindsborg. Near the Great Bend of the Arkansas River, in a place he called Quivira, he met the ancestors of the Wichita people. Near the Smoky Hill River, he met the Harahey, who were probably the ancestors of the Pawnee. This was the first time that the Plains Indians had seen horses. Later, they acquired horses from the Spanish, and rapidly radically altered their lifestyle and range.

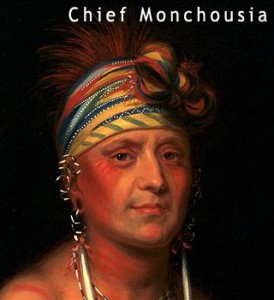

Following this transformation, the Kansa (sometimes Kaw) and Osage Nation (originally Ouasash) arrived in Kansas in the 17th century. (The Kansa claimed that they occupied the territory since 1673.) By the end of the 18th century, these two tribes were dominant in the eastern part of the future state: the Kansa on the Kansas River to the North and the Osage on the Arkansas River to the South. At the same time, the Pawnee (sometimes Paneassa) were dominant on the plains to the west and north of the Kansa and Osage nations, in regions home to massive herds of bison. Europeans visited the Northern Pawnee in 1719. The French commander at Fort Orleans, Etienne de Bourgmont, visited the Kansas River in 1724 and established a trading post there, near the main Kansa village at the mouth of the river. Around the same time, the Otoe tribe of the Sioux also inhabited various areas around the northeast corner of Kansas.

Louisiana Purchase

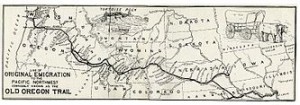

Frank Bond’s illustration of the Louisiana Purchase. The Ox Team or the Old Oregon Trail 1852–1906 by Ezra Meeker.

Frank Bond’s illustration of the Louisiana Purchase. The Ox Team or the Old Oregon Trail 1852–1906 by Ezra Meeker.

Apart from brief explorations, neither France nor Spain had any settlement or military or other activity in Kansas. In 1763, following the Seven Years War in which Great Britain defeated France, Spain acquired the French claims west of the Mississippi River. It returned this territory to France in 1803, keeping title to about 7,500 square miles (19,000 km2).

In the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, the United States (US) acquired all of the French claims west of the Mississippi River; the area of Kansas was unorganized territory. In 1819 the United States confirmed Spanish rights to the 7,500 square miles (19,000 km2) as part of the Adams-Onis Treaty with Spain. That area became part of Mexico, which also ignored it. After the Mexican-American War and the US victory, the United States took over that part in 1848.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition left St. Louis on a mission to explore the Louisiana Purchase all the way to the Pacific Ocean. In 1804, Lewis and Clark camped for three days at the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri rivers in present-day Kansas City, Kansas (today recognized at the Kaw Point Riverfront Park). They met French fur traders and mapped the area. In 1806, Zebulon Pike passed through Kansas and labeled it “the Great American Desert” on his maps. This view of Kansas would help form U.S. policy for the next 40 years, prompting the government to set it aside as land reserved for Native American resettlement.

After a brief period as part of Missouri Territory, Kansas returned to unorganized status in 1821. In 1821, the Santa Fe Trail was opened across Kansas as country’s transportation route to the Southwest, connecting Missouri with the well-established Santa Fe, New Mexico. Because of the burgeoning trade, the United States Army set up posts throughout the area. On May 8, 1827, Cantonment Leavenworth, or Fort Leavenworth, was built to protect travelers.

A section of the Santa Fe Trail through Kansas was used by emigrants on the Oregon Trail, which opened in 1841. The westward trails served as vital commercial and military highways until the railroad took over this role in the 1860s. To travelers en route toUtah, California, or Oregon, Kansas was an essential way stop and outfitting location. Wagon Bed Spring (also Lower Spring or Lower Cimarron Spring) was an important watering spot on the Cimarron Cutoff of the Santa Fe Trail. Other important locations along the trail were the Point of Rocks and Pawnee Rock

Beginning in the 1820s, the area that would become Kansas was set aside as Indian territory by the U.S. government, and was closed to settlement by whites. The government resettled to Indian Territory (now part of Oklahoma) those Native American tribes based in eastern Kansas, principally the Kansaand Osage, opening land to move eastern tribes into the area. By treaty dated June 3, 1825, 20 million acres (81000 km²) of land was ceded by the Kansa Nation to the United States, and the Kansa tribe was limited to a specific reservation in northeast Kansas. In the same month, the Osage Nation was limited to a reservation in southeast Kansas.

The Missouri Shawano (or Shawnee) were the first Native Americans removed to the territory. By treaty made at St. Louis on November 7, 1825, the United States agreed to provide:

- “The Shawanoe tribe of Indians within the State of Missouri, for themselves, and for those of the same nation now residing in Ohio who may hereafter immigrate to the west of the Mississippi, a tract of land equal to fifty miles [80 km] square, situated west of the State of Missouri, and within the purchase lately made from the Osage.”

The Delaware came to Kansas from Ohio and other eastern areas by the treaty of September 24, 1829. The treaty described:

- “The country in the fork of the Kansas and Missouri Rivers, extending up the Kansas River to the Kansas (Indian’s) line, and up the Missouri River to Camp Leavenworth, and thence by a line drawn westerly, leaving a space ten miles (16 km) wide, north of the Kansas boundary line, for an outlet.”

Map of Indian territories, 1836

Map of Indian territories, 1836

After this point, the Indian Removal Act of 1830 expedited the process. By treaty dated August 30, 1831, the Ottawa ceded land to the United States and moved to a small reservation on the Kansas River and its branches. The treaty was ratified April 6, 1832. On October 24, 1832, the U.S. government moved the Kickapoos to a reservation in Kansas. On October 29, 1832, the Piankeshaw and Wea agreed to occupy 250 sections of land, bounded on the north by the Shawanoe; east by the western boundary line of Missouri; and west by theKaskaskia and Peoria peoples. By treaty made with the United States on September 21, 1833, the Otoe tribe ceded their country south of the Little Nemaha River.

By September 17, 1836 the confederacy of the Sac and Fox, by treaty with the United States, moved north of Kickapoo. By treaty of February 11, 1837, the United States agreed to convey to the Pottawatomi an area on the Osage River, southwest of the Missouri River. The tract selected was in the southwest part of what is now Miami County.

In 1842, after a treaty between the United States and the Wyandots, the Wyandot moved to the junction of the Kansas and Missouri Rivers (on land that was shared with the Delaware until 1843). In an unusual provision, 35 Wyandot were given “floats” in the 1842 treaty – ownership of sections of land that could be located anywhere west of the Missouri River. In 1847, the Pottawatomi were moved again, to an area containing 576,000 acres (2,330 km²), being the eastern part of the lands ceded to the United States by the Kansa tribe in 1846. This tract comprised a part of the present counties of Pottawatomie, Wabaunsee, Jackson and Shawnee.

Early 1850’s and the territory organization

Despite the extensive plans that were made to settle Native Americans in Kansas, by 1850 white Americans were illegally squatting on their land and clamoring for the entire area to be opened for settlement. Presaging event that were soon to come, several U.S. Army forts, including Fort Riley, were soon established deep in Indian Territory to guard travelers on the various Western trails.

Although the Cheyennes and Arapahoes tribes were still negotiating with the United States for land in western Kansas (the current state of Colorado) – they signed a treaty on September 17, 1851 – momentum was already building to settle the land.

Kansas-Nebraska Act – Main article: Kansas-Nebraska Act

Congress began the process of creating Kansas Territory in 1852. That year, petitions were presented at the first session of the Thirty-second Congress for a territorial organization of the region lying west of Missouri and Iowa. No action was at that time taken. However, during the next session, on December 13, 1852, a Representative from Missouri submitted to the House a bill organizing the Territory of Platte: all the tract lying west of Iowa and Missouri, and extending west to the Rocky Mountains. The bill was referred to the United States House Committee on Territories, and passed by the full U.S. House of Representatives on February 10, 1853. However, Southern Senators stalled the progression of the bill in the Senate, while the implications of the bill on slavery and the Missouri Compromise were debated. Heated debate over the bill and other competing proposals would continue for a year, before eventually resulting in the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which became law on May 30, 1854, establishing the Nebraska Territory and Kansas Territory.

Native American territory ceded

Meanwhile, by the summer of 1853, it was clear that eastern Kansas would soon be opened to American settlers. The Commissioner of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, negotiated new treaties that would assign new reservations with annual federal subsidies for the Indians. Nearly all the tribes in the eastern part of the Territory ceded the greater part of their lands prior to the passage of the Kansas territorial act in 1854, and were eventually moved south to the future state of Oklahoma.

Chippewa named “One-Called-From-A-Distance”

Chippewa named “One-Called-From-A-Distance”

In the three months immediately preceding the passage of the bill, treaties were quietly made at Washington with the Delaware, Otoe, Kickapoo, Kaskaskia, Shawnee, Sac, Fox and other tribes, whereby the greater part of eastern Kansas, lying within one or two hundred miles of the Missouri border, was suddenly opened to white settlement. (The Kansa reservation had already been reduced by treaty in 1846.) On March 15, 1854, Otoe and Missouri Indians ceded to the United States all their lands west of the Mississippi, except a small strip on the Big Blue River. On May 6 and May 10, 1854, the Shawnees ceded 6,100,000 acres (25,000 km2), reserving only 200,000 acres (810 km2) for homes. Also on May 6, 1854, the Delaware ceded all their lands to the United States, except a reservation defined in the treaty. On May 17, the Iowa similarly ceded their lands, retaining only a small reservation. On May 18, 1854, the Kickapoo too ceded their lands, except 150,000 acres (610 km2) in the western part of the Territory. In 1854 lands were also ceded by the Kaskaskia, Peoria, Piankeshaw and Wea and by the Sac and Fox.

The final step in Americanizing the Indians was taking land from tribal control and assigning it to individual Indian households, to buy and sell as European Americans would. For example, in 1854, the Chippewa (Swan Creek and Black River bands) inhabited 8,320 acres (33.7 km2) in Franklin County, but in 1859 the tract was transferred to individual Chippewa families.

Kansas Territory – Main article: Kansas Territory

Upon the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act on May 30, 1854, the borders of Kansas Territory were set from the Missouri border to the summit of the Rocky Mountain range (now in central Colorado); the southern boundary was the 37th parallel north, the northern was the 40th parallel north. North of the 40th parallel was Nebraska Territory. When Congress set the southern border of the Kansas Territory as the 37th parallel, it was thought that the Osage southern border was also the 37th parallel. The Cherokees immediately complained, saying that it was not the true boundary and that the border of Kansas should be moved north to accommodate the actual border of the Cherokee land. This became known as the Cherokee Strip controversy.

An invitation to violence

The most controversial provision in the Kansas-Nebraska Act was the stipulation that settlers in Kansas Territory would vote on whether to allow slavery within its borders. This provision repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had prohibited slavery in any new states created north of latitude 36°30′. Predictably, violence resulted between the Northerners and Southerners who rushed to settle there in order to control the vote.

Within a few days after the passage of the Act, hundreds of pro-slavery Missourians crossed into the adjacent territory, selected an area of land, and then united with other Missourians in a meeting or meetings, intending to establish a pro-slavery preemption upon the entire region. As early as June 10, 1854, the Missourians held a meeting at Salt Creek Valley, a trading post three miles (5 km) west of Fort Leavenworth, at which a “Squatter’s Claim Association” was organized. They said they were in favor of making Kansas a slave state, if it should require half the citizens of Missouri, musket in hand, to emigrate there, and even to sacrifice their lives in accomplishing this end.

To counter this action, the Massachusetts Emigrant Aid Company (and other smaller organizations) quickly arranged to send anti-slavery settlers (known as “Free-Staters“) into Kansas in 1854 and 1855. The principal towns founded by the New Englanders were Topeka, Manhattan, and Lawrence. Several Free-State men also came to Kansas Territory from Ohio, Iowa, Illinois and other Midwestern states.

Bleeding Kansas

1855 Free-State poster – Main article: Bleeding Kansas

1855 Free-State poster – Main article: Bleeding Kansas

Despite the proximity and opposite aims of the settlers, the lid was largely kept on the violence until the election of the Kansas Territorial legislature on March 30, 1855. On that date, Missourians who had streamed across the border (known as “Border Ruffians“) filled the ballot boxes in favor of pro-slavery candidates. As a result, pro-slavery candidates prevailed at every polling district except one (the future Riley County), and the first official legislature was overwhelmingly composed of pro-slavery delegates.

From 1855 to 1858, Kansas Territory experienced extensive violence and some open battles. This period, known as “Bleeding Kansas” or “the Border Wars,” directly presaged the American Civil War. The major incidents of Bleeding Kansas include the Wakarusa War, the Sacking of Lawrence, the Pottawatomie Massacre, the Battle of Black Jack, theBattle of Osawatomie, and the Marais des Cygnes massacre.

- Wakarusa War – Main article: Wakarusa War

On December 1, 1855, a small army of Missourians, acting under the command of Douglas County, Kansas Sheriff Samuel J. Jones laid siege to the Free-State stronghold of Lawrence in what would later become known as “The Wakarusa War.” A treaty of peace negotiation was announced amid much disorder and cries for the reading of the treaty shortly afterwards. It quelled the disorder and its provisions were generally accepted.

- Sacking of Lawrence – Main article: Sacking of Lawrence

On May 21, 1856, pro-slavery forces led by Sheriff Jones attacked Lawrence, killing two men, burning the Free-State Hotel to the ground, destroying two printing presses, and robbing homes.

- Pottawatomie Massacre – Main article: Pottawatomie Massacr

The Pottawatomie Massacre occurred during the night of May 24 to the morning of May 25, 1856. In what appears to be a reaction to the Sacking of Lawrence, John Brown and a band ofabolitionists (some of them members of the Pottawatomie Rifles) killed five settlers, thought to be pro-slavery, north of Pottawatomie Creek in Franklin County, Kansas. Brown later said that he had not participated in the killings during the Pottawatomie Massacre, but that he did approve of them. He went into hiding after the killings, and two of his sons, John Jr. and Jason, were arrested. During their confinement, they were allegedly mistreated, which left John Jr. mentally scarred. On June 2, Brown led a successful attack on a band of Missourians led by Captain Henry Pate in the Battle of Black Jack. Pate and his men had entered Kansas to capture Brown and others. That autumn, Brown went back into hiding and engaged in other guerrilla warfare activities.

Territorial constitutions

The violently feuding pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions tried to defeat the opposition by pushing through their own version of a state constitution, that would either endorse or condemn slavery. Congress had the final say.