Italian Cuisine

Italian Spaghetti Bolognese Recipe : History of Spaghetti Bolognese

Learn the history of the spaghetti Bolognese recipe with expert cooking tips in this free traditional Italian recipe video clip. Expert: Graziano Cattaneo, Bio: Krizia Restaurant is the result of 25 years of culinary experience & expertise on the part of owner & chef Graziano Cattaneo. Filmmaker: Paul (Leopold) Volniansky.

Italian cuisine (Italian: cucina italiana, IPA: [kuˈtʃiːna itaˈljaːna]) has developed through centuries of social and political changes, with roots as far back as the 4th century BCE. Italian cuisine in itself takes heavy influences, including Etruscan, ancient Greek, ancient Roman, Byzantine, and Jewish. Significant changes occurred with the discovery of the New World with the introduction of items such as potatoes, tomatoes, bell peppers andmaize, now central to the cuisine but not introduced in quantity until the 18th century. Italian cuisine is noted for its regional diversity, abundance of difference in taste, and is known to be one of the most popular in the world, with influences abroad.

Italian cuisine (Italian: cucina italiana, IPA: [kuˈtʃiːna itaˈljaːna]) has developed through centuries of social and political changes, with roots as far back as the 4th century BCE. Italian cuisine in itself takes heavy influences, including Etruscan, ancient Greek, ancient Roman, Byzantine, and Jewish. Significant changes occurred with the discovery of the New World with the introduction of items such as potatoes, tomatoes, bell peppers andmaize, now central to the cuisine but not introduced in quantity until the 18th century. Italian cuisine is noted for its regional diversity, abundance of difference in taste, and is known to be one of the most popular in the world, with influences abroad.

Italian cuisine is characterized by its extreme simplicity, with many dishes having only four to eight ingredients. Italian cooks rely chiefly on the quality of the ingredients rather than on elaborate preparation. Ingredients and dishes vary by region. Many dishes that were once regional, however, have proliferated with variations throughout the country.

Cheese and wine are a major part of the cuisine, with many variations and Denominazione di origine controllata (DOC) (regulated appellation) laws. Coffee, specifically espresso, has become important in Italian cuisine.

History

Italian cuisine has developed over the centuries. Although the country known as Italy did not unite until the 19th century, the cuisine can claim traceable roots as far back as the 4th century BCE. Through the centuries, neighbouring regions, conquerors, high-profile chefs, political upheaval and the discovery of the New World have influenced its development.

Antiquity – See also: Ancient Roman cuisine

Apicius‘, De re coquinaria, 1709 edition.

Apicius‘, De re coquinaria, 1709 edition.

The first known Italian food writer was a Greek Sicilian named Archestratus from Syracuse in the 4th century BCE. He wrote a poem that spoke of using “top quality and seasonal” ingredients. He said that flavors should not be masked by spices, herbs or other seasonings. He placed importance on simple preparation of fish. This style seemed to be forgotten during the 1st century CE when De re coquinaria was published with 470 recipes calling for heavy use of spices and herbs. The Romans employed Greek bakers to produce breads and imported cheeses from Sicily as the Sicilians had a reputation as the best cheesemakers. The Romans reared goats for butchering, and grew artichokes and leeks.

Middle Ages – See also: Medieval cuisine

With culinary traditions from Rome and Athens, a cuisine developed in Sicily that some consider the first real Italian cuisine. Arabs invaded Sicily in the 9th century. The Arabs introduced spinach, almonds, and rice. During the 12th century, a Norman king surveyed Sicily and saw people making long strings made from flour and water called atriya, which eventually became trii, a term still used for spaghetti in southern Italy. Normans also introduced casseroles, salt cod (baccalà) and stockfish which remain popular.

Food preservation was either chemical or physical, as refrigeration did not exist. Meats and fish would be smoked, dried or kept on ice. Brine and salt were used to pickle items such as herring, and to cure pork. Root vegetables were preserved in brine after they had been parboiled. Other means of preservation included oil, vinegar or immersing meat in congealed, rendered fat. For preserving fruits, liquor, honey and sugar were used.

The northern Italian regions show a mix of Germanic and Roman culture while the south reflects Arab influence, as much Mediterranean cuisine was spread by Arab trade. The oldest Italian book on cuisine is the 13th century Liber de coquina written in Naples. Dishes include “Roman-style” cabbage (ad usum romanorum), ad usum campanie which were “small leaves” prepared in the “Campanian manner”, a bean dish from the Marca di Trevisio, a torta, compositum londardicum which are similar to dishes prepared today. Two other books from the 14th century include recipes for Roman pastello, Lavagna pie, and call for the use of salt from Sardinia or Chioggia.

In the 15th century, Maestro Martino was chef to the Patriarch of Aquileia at the Vatican. HisLibro de arte coquinaria describes a more refined and elegant cuisine. His book contains a recipe for Maccaroni Siciliani, made by wrapping dough around a thin iron rod to dry in the sun. The macaroni was cooked in capon stock flavored with saffron, displaying Persian influences. Of particular note is Martino’s avoidance of excessive spices in favor of fresh herbs. The Roman recipes include coppiette and cabbage dishes. His Florentine dishes include eggs with Bolognese torta, Sienese torta and Genoese recipes such as piperata, macaroni, squash, mushrooms, and spinach pie with onions.

Martino’s text was included in a 1475 book by Bartolomeo Platina printed in Venice entitled De honesta voluptate et valetudine (“On Honest Pleasure and Good Health”). Platina puts Martino’s “Libro” in regional context, writing about perch from Lake Maggiore, sardines from Lake Garda,grayling from Adda, hens from Padua, olives from Bologna and Piceno, turbot from Ravenna, rudd from Lake Trasimeno, carrots from Viterbo, bass from the Tiber, roviglioni and shad from Lake Albano, snails from Rieti, figs from Tuscolo, grapes from Narni, oil from Cassino, oranges from Naples and eels from Campania. Grains from Lombardy and Campania are mentioned as is honey from Sicily and Taranto. Wine from the Ligurian coast, Greco from Tuscany and San Severino and Trebbiano from Tuscany and Piceno are also in the book.

Early modern era

The courts of Florence, Rome, Venice and Ferrara were central to the cuisine. Cristoforo di Messisbugo, steward to Ippolito d’Este, published Banchetti Composizioni di Vivande in 1549. Messisbugo gives recipes for pies and tarts (containing 124 recipes with various fillings). The work emphasizes the use of Eastern spices and sugar.

Bartolomeo Scappi personal chef to Pope Pius V.

Bartolomeo Scappi personal chef to Pope Pius V.

In 1570, Bartolomeo Scappi, personal chef to Pope Pius V, wrote his Opera in five volumes, giving a comprehensive view of Italian cooking of that period. It contains over 1,000 recipes, with information on banquets including displays and menus as well as illustrations of kitchen and table utensils. This book differs from most books written for the royal courts in its preference for domestic animals and courtyard birds rather than game.

Recipes include lesser cuts of meats such as tongue, head and shoulder. The third volume has recipes for fish in Lent. These fish recipes are simple, including poaching, broiling, grilling and frying after marination.

Particular attention is given to seasons and places where fish should be caught. The final volume includes pies, tarts, fritters and a recipe for a sweet Neapolitan pizza (not the current savory version, as tomatoes had not been introduced to Italy. However, such items from the New World as corn (maize) and turkey are included.

L’arte di Ben Cucinare published by Bartolomeo Stefani in 1662.

L’arte di Ben Cucinare published by Bartolomeo Stefani in 1662.

In the first decade of the 17th century, Giangiacomo Castelvetro wroteBreve Racconto di Tutte le Radici di Tutte l’Herbe et di Tutti i Frutti (A Brief Account of All Vegetables, Herbs and Fruit), translated into English by Gillian Riley. Originally from Modena, Castelvetro moved to England because he was a Protestant. The book has a list of Italian vegetables and fruits and their preparation. He featured vegetables as a central part of the meal, not just accompaniments. He favored simmering vegetables in salted water and serving them warm or cold with olive oil, salt, fresh ground pepper, lemon juice or verjus or orange juice. He also suggests roasting vegetables wrapped in damp paper over charcoal or embers with a drizzle of olive oil. Castelvetro’s book is separated into seasons with hop shoots in the spring and truffles in the winter, detailing the use of pigs in the search for truffles.

In 1662, Bartolomeo Stefani, chef to the Duchy of Mantua, published L’Arte di Ben Cucinare. He was the first to offer a section on vitto ordinario (“ordinary food”). The book described a banquet given by Duke Charles for Queen Christina of Sweden, with details of the food and table settings for each guest, including a knife, fork, spoon, glass, a plate (instead of the bowls more often used) and a napkin. Other books from this time, such as Galatheo by Giovanni della Casa, tell how scalci (“waiters”) should manage themselves while serving their guests. Waiters should not scratch their heads or other parts of themselves, or spit, sniff, cough or sneeze while serving diners. The book also told diners not to use their fingers while eating and not to wipe sweat with their napkin.

Modern era

Small pasta machine designed to mangle lasagne and cut tagliatelle, an example of modern technology used to shape the oldest culinary traditions.

Small pasta machine designed to mangle lasagne and cut tagliatelle, an example of modern technology used to shape the oldest culinary traditions.

At the beginning of the 18th century, Italian culinary books began to emphasize the regionalism of Italian cuisine rather than French cuisine. Books written then were no longer addressed to professional chefs but to bourgeois housewives. Periodicals in booklet form such as La cuoca cremonese (“The Cook of Cremona”) in 1794 give a sequence of ingredients according to season along with chapters on meat, fish and vegetables. As the century progressed these books increased in size, popularity and frequency.

Cucina Borghese published by Chef Giovanni Vialardi in 19th century.

Cucina Borghese published by Chef Giovanni Vialardi in 19th century.

In the 18th century, medical texts warned peasants against eating refined foods as it was believed that these were poor for their digestion and their bodies required heavy meals. It was believed by some that peasants ate poorly because they preferred eating poorly. However, many peasants had to eat rotten food and moldy bread because that was all they could afford.

In 1779, Antonio Nebbia from Macerata in the Marche region, wrote Il Cuoco Maceratese (“The Cook of Macerata”). Nebbia addressed the importance of local vegetables and pasta, rice and gnocchi. For stock, he preferred vegetables and chicken over meat.

In 1773, the Neopolitan Vincenzo Corrado’s Il Cuoco Galante (“The Courteous Cook”) gave particular emphasis to Vitto Pitagorico(vegetarian food). “Pitagoric food consists of fresh herbs, roots, flowers, fruits, seeds and all that is produced in the earth for our nourishment. It is so called because Pythagoras, as is well known, only used such produce. There is no doubt that this kind of food appears to be more natural to man, and the use of meat is noxious.” This book was the first to give the tomato a central role with thirteen recipes.

Zuppa alli Pomidoro in Corrado’s book is a dish similar to today’s Tuscan Pappa al Pomodoro. Corrado’s 1798 edition introduced a “Treatise on the Potato” after the French Antoine-Augustin Parmentier‘s successful promotion of it. In 1790, Francesco Leonardi in his book L’Apicio moderno (“Modern Apicius“) sketches a history of the Italian Cuisine from the Roman Age and gives as first a recipe of a tomato based sauce.

In the 19th century, Giovanni Vialardi, chef to King Victor Emmanuel, wrote A Treatise of Modern Cookery and Patisserie with recipes “suitable for a modest household”. Many of his recipes are for regional dishes from Turin including twelve for potatoes such as Genoese Cappon Magro. In 1829, Il Nuovo Cuoco Milanese Economico by Giovanni Felice Luraschi features Milanese dishes such as Kidney with Anchovies and Lemon and Gnocchi alla Romana. Gian Battista and Giovanni Ratto’s La Cucina Genovese in 1871 addressed the cuisine of Liguria. This book contained the first recipe for pesto. La Cucina Teorico-Pratica written by Ippolito Cavalcanti has the first recipe for pasta with tomatoes. La scienza in cucina e l’arte di mangiare bene (“The Science of Cooking and the Art of Eating Well”), by Pellegrino Artusi, first published in 1891, is widely regarded as the canon of classic modern Italian cuisine, and it is still in print. Its recipes come mainly from Romagna and Tuscany, where he lived.

Ingredients

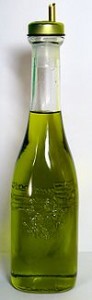

Olive oil is the most commonly used vegetable fat in Italian cooking, and as the basis for sauces, often replaces animal fats of butter or lard.

Olive oil is the most commonly used vegetable fat in Italian cooking, and as the basis for sauces, often replaces animal fats of butter or lard.

Pesto, a Ligurian sauce made out of basil, olive oil and nuts, and which is eaten with pasta.

Pesto, a Ligurian sauce made out of basil, olive oil and nuts, and which is eaten with pasta.

Italian cuisine has a great variety of different ingredients which are commonly used, ranging from fruits, vegetables, sauces, meats, etc. In the North of Italy, fish (such as cod, or baccalà), potatoes, rice, corn (maize), sausages, pork, and different types of cheeses are the most common ingredients. Pasta dishes with lighter use of tomato are found in Trentino-Alto Adige and Emilia Romagna.

In Northern Italy though there are many kinds of stuffed pasta, polenta and risotto are equally popular if not more so. Ligurian ingredients include several types of fish and seafood dishes; basil (found in pesto), nuts and olive oil are very common. In Emilia-Romagna, common ingredients include ham (prosciutto), sausage (cotechino), different sorts of salami, truffles, grana, Parmigiano-Reggiano, and tomatoes (Bolognese sauce or ragù).

Traditional Central Italian cuisine uses ingredients such as tomatoes, all kinds of meat, fish, and pecorino cheese. In Tuscany and Umbria pasta is usually served alla carrettiara (a tomato sauce spiked with peperoncini hot peppers). Finally, in Southern Italy, tomatoes – fresh or cooked into tomato sauce – peppers, olives and olive oil, garlic, artichokes, oranges, ricotta cheese, eggplants, zucchini, certain types of fish (anchovies, sardines and tuna), and capers are important components to the local cuisine.

Italian cuisine is also well known (and well regarded) for its use of a diverse variety of pasta. Pasta include noodles in various lengths, widths and shapes. Distinguished on shapes they are named — penne, macaroni, spaghetti, linguine, fusilli, lasagne and many more varieties that are filled with other ingredients like ravioli and tortellini.

The word pasta is also used to refer to dishes in which pasta products are a primary ingredient. It is usually served with sauce. There are hundreds of different shapes of pasta with at least locally recognized names.

Examples include spaghetti (thin rods), rigatoni (tubes or cylinders), fusilli (swirls), and lasagne (sheets). Dumplings, like gnocchi (made with potatoes) and noodles like spätzle, are sometimes considered pasta. They are both traditional in parts of Italy.

Pasta is categorized in two basic styles: dried and fresh. Dried pasta made without eggs can be stored for up to two years under ideal conditions, while fresh pasta will keep for a couple of days in the refrigerator. Pasta is generally cooked by boiling. Under Italian law, dry pasta (pasta secca) can only be made from durum wheat flour or durum wheat semolina, and is more commonly used in Southern Italy compared to their Northern counterparts, who traditionally prefer the fresh egg variety. Durum flour and durum semolina have a yellow tinge in color. Italian pasta is traditionally cooked al dente (Italian: “firm to the bite”, meaning not too soft). Outside Italy, dry pasta is frequently made from other types of flour (such as wheat flour), but this yields a softer product that cannot be cooked al dente. There are many types of wheat flour with varying gluten and protein depending on variety of grain used.

Particular varieties of pasta may also use other grains and milling methods to make the flour, as specified by law. Some pasta varieties, such as pizzoccheri, are made from buckwheat flour. Fresh pasta may include eggs (pasta all’uovo ‘egg pasta’). Whole wheat pasta has become increasingly popular because of its health benefits over pasta made from refined flour.