History of the Jews in the United States

Faith and Fate

Faith and Fate is a documentary telling the story of the Jews in the 20th Century.

The first Episode is called, “The Dawn of the Century” and covers 1900 – 1910. This episode introduces the uniqueness of Jewish history in the 20th century within the

context of world history. At the turn of the 20th century, Jews were scattered across the

globe, representing only ¼ of one percent of the worlds population. It was a time of

empires, imperial rule and colonial expansionism. In Russia the masses, including the

Jews, lived in dire poverty which was compounded by grassroots antisemitism. In 1905

the Russian masses revolted and there was a general strike. On Bloody Sunday the

Czar responded with force. The Czar did not abdicate until 1917, which is typically the

date given for the second Russian Revolution, which, in turn, led to increased pogroms

against the Jews. The pogroms and the economic conditions forced approximately

40% of Jewish population to leave the Russian Empire and go to Western countries

including the United States and to Palestine and other countries as far away as South

Africa and Australia.

Emigration and the Enlightenment presented Jews with the dilemma and opportunity to

maintain or reject their traditional Jewish upbringing, and many decided to forgo their

traditional Judaism and blend in with their larger non-Jewish society. Within the

traditional Jewish world, change was occurring as well, with the rise and acceptance of

the Mussar Movement, an ethical approach to Judaism. Because Jews were not

allowed into institutions of higher education in Eastern Europe, most of them went to

study in yeshivas to sharpen their intellect. The traditional yeshiva, unintentionally,

became a breeding ground for all philosophies, Jewish and secular alike. Zionism

grew as a national movement, and was led by secular Jews antithetical to traditional

Judaism. While most rabbis rejected Zionism and its leaders, because of their

nontraditional beliefs, a minority of rabbis developed religious Zionism, which combined

traditional Judaism with Zionist philosophy. The Old Yishuv Jews, who had settled in

Palestine in the late 1800s, were committed to traditional Judaism and rejected

secular, nationalistic ideas of the New Yishuv Zionists.

The Sephardic Jews living in Moslem and Arab countries at the turn of the 20th

Century maintained their own rich Jewish traditions and heritage, which often differed

from those of the Ashkenazim. There was relative peace within the Jewish community

and among the leadership in these Arab and Moslem countries, and although life was

sometimes difficult, these Sephardic Jews did not experience, by and large, pogroms

or the influences of the Enlightenment or Reform Judaism.

In Europe, Jews were the leaders of the Labor and Socialist movements and

spearheaded the establishment of labor unions in America. The challenge of

assimilation in the United States was the greatest difficulty confronting Jewish

immigrants. Attempts were made to stem the tide. Reform Judaism became a symbol

of acceptance into modern American society and Dr. Solomon Schechter initiated the

Universal Synagogue movement which became Conservative Judaism. Also

Sephardic and Ashkenazic Jewish immigrants had to find their respective places within

the Jewish community and in their new host country, the United States, as well..

A small, strong group of American Jewish immigrants managed to cling to their Jewish

traditions and adapt themselves to the new reality in America. Meanwhile, for Jews

around the world, with the threat of WWI looming, the imperial race for supremacy was

escalating.

The history of the Jews in the United States (United States of America), has been part of the American national fabric since colonial times.

The history of the Jews in the United States (United States of America), has been part of the American national fabric since colonial times.

Until the 1830s the Jewish community of Charleston, South Carolina was the most numerous in North America. With the large scale immigration of Jews from diaspora communities in Germany in the 19th century, they established themselves in many small towns and cities. A much larger immigration of Eastern Ashkenazi Jews, 1880–1914, brought a large, poor, traditional element to New York City. Refugees arrived from diaspora communities in Europe after World War II, and many arrived from the Soviet Union after 1970.

In the 1940’s Jews comprised 3.7% of the national population. Today the population is about 5 million—under 2% of the national total—and shrinking because of small family sizes and intermarriage. The largest population centers are the metropolitan areas of New York (2.1 million in 2000), Los Angeles (668,000), Miami (331,000), Philadelphia (285,000), Chicago (265,000) and Boston (254,000).

The Jewish population of the US is the product of waves of immigration primarily from diaspora communities in Europe; it was initially inspired by the pull of social and entrepreneurial opportunities, and later as a refuge from the push of continuing antisemitismthere. Few ever returned to Europe, although committed advocates of Zionism have made aliyah to Israel.

America and its culture developed as an easy-to-enter “Melting Pot” for many cultures, creating a new commonality of culture and political values. This open culture allowed many minority groups, including Jews, to flourish in Christian and predominantly Protestant America. Antisemitism in the United States has always been less common than in other historic areas of Jewish population, whether in Christian Europe or in the Muslim parts of the Middle East, where most nations developed around different majority ethnicities or languages.

From a population of 1000-2000 Jewish residents in 1790, mostly Dutch Sephardic Jews, Jews from England, and British subjects, the American Jewish community grew to about 15,000 by 1840, and to about 250,000 by 1880. Most of the mid-19th century Ashkenazi Jewish immigrants to the US came from diaspora communities in German-speaking states, in addition to the larger concurrent indigenous German migration. They all initially spoke German, and settled across the nation, assimilating with their new countrymen; the Jews among them commonly engaged in trade, manufacturing, and operated dry goods (clothing) stores in many cities.

Between 1880 and the start of World War I in 1914, about two million Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazi Jews immigrated from diaspora communities in Eastern Europe, where repeated pogroms made life untenable. They came from Jewish diaspora communities of Russia, the Pale of Settlement (modern Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova), and the Russian-controlled portions of Poland. The latter group clustered in New York City, created the garment industry there, which supplied the dry goods stores across the country, and were heavily engaged in the trade unions. They immigrated alongside indigenous eastern and southern European immigrants, which was unlike the historically predominant American demographic from northern and western Europe; Records indicate between 1880 and 1920 that these new immigrants rose from less than five percent of all European immigrants to nearly 50%. This feared change caused renewed nativist sentiment, the birth of the Immigration Restriction League, and congressional studies by the Dillingham Commission from 1907 to 1911. The Emergency Quota Act of 1921 established immigration restrictions specifically on these groups, and the Immigration Act of 1924 further tightened and codified these limits. With the ensuing Great Depression, and despite worsening conditions for Jews in Europe, with the rise of Nazi Germany, these quotas remained in place with minor alterations until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

Jews quickly created support networks consisting of many small synagogues and Ashkenazi Jewish Landsmannschaften (German for “Territorial Associations”) for Jews from the same town or village.

Leaders of the time urged assimilation and integration into the wider American culture, and Jews quickly became part of American life. During World War II, 500,000 American Jews, about half of all Jewish males between 18 and 50, enlisted for service, and after the war, Jewish families joined the new trend of suburbanization, as they became wealthier and more mobile. The Jewish community expanded to other major cities, particularly around Los Angeles and Miami. Their young people attended secular high schools and colleges and met Christians, so that intermarriage rates soared to nearly 50%. Synagogue membership however, grew considerably, from 20% of the Jewish population in 1930 to 60% in 1960.

The earlier waves of immigration and immigration restriction were followed by the Holocaust that destroyed most of the European Jewish community by 1945; these also made the United States the home for the largest Jewish diaspora population in the world. In 1900 there were 1.5 million Americans Jews; in 2005 there were 5.3 million. See Historical Jewish population comparisons

On a theological level, American Jews are divided into a number of Jewish denominations, of which the most numerous are Reform Judaism, Conservative Judaism and Orthodox Judaism. However, roughly 25% of American Jews are unaffiliated with any denomination. Conservative Judaism arose in America and Reform Judaism was founded in Germany and popularized by American Jews.

Colonial era: Jewish history in Colonial America

Touro Synagogue, built in 1759 in Newport, Rhode Island, is America’s oldest surviving synagogue

Touro Synagogue, built in 1759 in Newport, Rhode Island, is America’s oldest surviving synagogue

The Gomez Mill House, built in 1714 near Marlboro, NY by a Sephardic Jew from Portugal. Earliest surviving Jewish residence in the U.S.

The Gomez Mill House, built in 1714 near Marlboro, NY by a Sephardic Jew from Portugal. Earliest surviving Jewish residence in the U.S.

The first Jew to set foot on American soil was Joachim Gans in 1584. Some people would argue that the first Jew was Luis de Carabajal y Cueva, a Spanish conquistador and converso, who first set foot in what is now Texas in 1554. Solomon Franco, a Jewish merchant, arrived in Boston in 1649; subsequently he was given a stipend from the Puritans there, on condition he leave on the next passage back to Holland. In September 1654, shortly before the Jewish New Year, twenty-three Jews from the Sephardic community in the Netherlands, coming from Recife, Brazil, then a Dutch colony, arrived in New Amsterdam (New York City). Governor Peter Stuyvesant tried to enhance his Dutch Reformed Church by discriminating against other religions, but religious pluralism was already a tradition in the Netherlands and his superiors at the Dutch West India Company in Amsterdam overruled him.

Religious tolerance was also established elsewhere in the colonies; the colony of South Carolina, for example, was originally governed under an elaborate charter drawn up in 1669 by the English philosopher John Locke. This charter granted liberty of conscience to all settlers, expressly mentioning “Jews, heathens, and dissenters.” As a result, Charleston, South Carolina has a particularly long historyof Sephardic settlement, which in 1816 numbered over 600, then the largest Jewish population of any city in the United States. Sephardic Dutch Jews were also among the early settlers of Newport (where the country’s oldest surviving synagogue building stands), Savannah, Philadelphia and Baltimore. In New York City, Shearith Israel Congregation is the oldest continuous congregation started in 1687 having their first synagogue erected in 1728, and its current building still houses some of the original pieces of that first. By the time of American Revolution, the Jewish population in America was very small, with only 1,000-2000, in a colonial population of about 2.5 million.

By 1776 and the War of Independence, around 2,000 Jews lived in America, most of them Sephardic Jews of Spanish and Portuguese origin. They played a significant role in the struggle for independence, including fighting the British, with Francis Salvador being the first Jew to die, and playing a key role in financing the revolution, with the most important of the financiers being Haym Solomon. Others, like David Salisbury Franksan, despite loyal service in both the Continental Army and the American diplomatic corps, suffered from his association as aide-de-camp for the traitorous general Benedict Arnold.

President George Washington remembered the Jewish contribution when he wrote to the Sephardic congregation of Newport, Rhode Island, in a letter dated August 17, 1790: “May the children of the stock of Abraham who dwell in the land continue to merit and enjoy the goodwill of the other inhabitants. While everyone shall sit safely under his own vine and fig-tree and there shall be none to make him afraid.”

In 1790, the approximate 2,500 Jews in America faced a number of legal restrictions in various states that prevented non-Christians from holding public office and voting, but Delaware, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Georgia soon eliminated these barriers, as did the Bill of Rights in 1791 generally. Sephardic Jews became active in community affairs in the 1790s, after achieving “political equality in the five states in which they were most numerous.” Other barriers did not officially fall for decades in the states of Rhode Island (1842), North Carolina (1868), and New Hampshire (1877). Despite these restrictions, which were often enforced unevenly, there were really too few Jews in 17th- and 18th-century America for anti-Jewish incidents to become a significant social or political phenomenon at the time. The evolution for Jews from toleration to full civil and political equality that followed the American Revolution helped ensure that Antisemitism would never become as common as in Europe.

19th century

Following traditional religious and cultural teachings about improving the lot of their brethren, Jewish residents in the United States began to organize their communities in the early 19th century. Early examples include a Jewish orphanage set up in Charleston, South Carolina in 1801, and the first Jewish school, Polonies Talmud Torah, established in New York in 1806. In 1843, the first national secular Jewish organization in the United States, the B’nai B’rith was established. See also History of Jewish education in the United States (pre-20th century).

Following traditional religious and cultural teachings about improving the lot of their brethren, Jewish residents in the United States began to organize their communities in the early 19th century. Early examples include a Jewish orphanage set up in Charleston, South Carolina in 1801, and the first Jewish school, Polonies Talmud Torah, established in New York in 1806. In 1843, the first national secular Jewish organization in the United States, the B’nai B’rith was established. See also History of Jewish education in the United States (pre-20th century).

Jewish Texans have been a part of Texas History since the first European explorers arrived in the 16th century. Spanish Texasdid not welcome easily identifiable Jews, but they came in any case. Jao de la Porta was with Jean Laffite at Galveston, Texas in 1816, and Maurice Henry was in Velasco in the late 1820s. Jews fought in the armies of the Texas Revolution of 1836, some with Fannin at Goliad, others at San Jacinto. Dr. Albert Levy became a surgeon to revolutionary Texan forces in 1835, participated in the capture of Béxar, and joined the Texas Navy the next year.

By 1840, Jews constituted a tiny, but nonetheless stable, middle-class minority of about 15,000 out of the 17 million Americans counted by the U.S. Census. Jews intermarried rather freely with non-Jews, continuing a trend that had begun at least a century earlier. However, as immigration increased the Jewish population to 50,000 by 1848, negative stereotypes of Jews in newspapers, literature, drama, art, and popular culture grew more commonplace and physical attacks became more frequent.

During the 19th century, (especially the 1840s and 1850s), Jewish immigration was primarily of Ashkenazi Jews from Germany, bringing a liberal, educated population that had experience with the Haskalah, or Jewish Enlightenment. It was in the United States during the 19th century that two of the major branches of Judaism were established by these German immigrants: Reform Judaism(out of German Reform Judaism) and Conservative Judaism, in reaction to the perceived liberalness of Reform Judaism.

Civil War

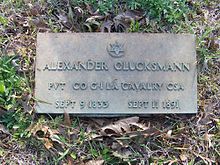

Grave of Jewish Confederate soldier near Clinton, Louisiana

Grave of Jewish Confederate soldier near Clinton, Louisiana

During the American Civil War, approximately 3,000 Jews (out of around 150,000 Jews in the United States) fought on the Confederate side and 7,000 fought on the Union side. Jews also played leadership roles on both sides, with nine Jewish generals and 21 Jewish colonels participating in the War. Judah P. Benjamin, a non-observant Jew, served as Secretary of State and acting Secretary of War of the Confederacy. Several Jewish bankers played key roles in providing government financing for both side of the Civil war: Speyer and Seligman family, for the Union, and Emile Erlanger and Company for the Confederacy.

By the time of the Civil War, tensions over race and immigration, as well as economic competition between Jews and non-Jews, combined to produce the worst outbreak of antisemitism to that date. Americans on both sides of the slavery issue denounced Jews as disloyal war profiteers, and accused them of driving Christians out of business and of aiding and abetting the enemy.

Major General Ulysses S. Grant was influenced by these sentiments and issued General Order No. 11 expelling Jews from areas under his control in western Tennessee:

The Jews, as a class violating every regulation of trade established by the Treasury Department and also department orders, are hereby expelled …within twenty-four hours from the receipt of this order.

This order was quickly rescinded by President Abraham Lincoln but not until it had been enforced in a number of towns.

Grant later issued an order “that no Jews are to be permitted to travel on the road southward.” His aide, Colonel John V. DuBois, ordered “all cotton speculators, Jews, and all vagabonds with no honest means of support”, to leave the district. “The Israelites especially should be kept out…they are such an intolerable nuisance.”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Jews_in_the_United_States