Harvey Milk

The Times of Harvey Milk – Trailer (1984)

The Oscar-winning The Times of Harvey Milk, was as groundbreaking as its subject. One of the first feature documentaries to address gay life in America, it’s a work of advocacy itself, bringing Milk’s message of hope and equality to a wider audience.

Harvey Bernard Milk (May 22, 1930 – November 27, 1978) was an American politician who became the first openly gay person to be elected to public office in California when he won a seat on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. Politics and gay activism were not his early interests; he was not open about his homosexuality and did not participate in civic matters until around the age of 40, after his experiences in the counterculture of the 1960’s.

Milk moved from New York City to settle in San Francisco in 1972 amid a migration of gay men to the Castro District. He took advantage of the growing political and economic power of the neighborhood to promote his interests, and ran unsuccessfully for political office three times. His theatrical campaigns earned him increasing popularity, and Milk won a seat as a city supervisor in 1977, part of the broader social changes the city was experiencing.

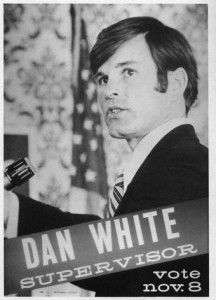

Milk served almost 11 months in office and was responsible for passing a stringent gay rights ordinance for the city. On November 27, 1978, Milk and Mayor George Moscone were assassinated by Dan White, another city supervisor who had recently resigned but wanted his job back. Milk’s election was made possible by and was a key component of a shift in San Francisco politics.

Despite his short career in politics, Milk became an icon in San Francisco and a martyr in the gay community. In 2002, Milk was called “the most famous and most significantly open LGBT official ever elected in the United States.” Anne Kronenberg, his final campaign manager, wrote of him: “What set Harvey apart from you or me was that he was a visionary. He imagined a righteous world inside his head and then he set about to create it for real, for all of us.” Milk was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009.

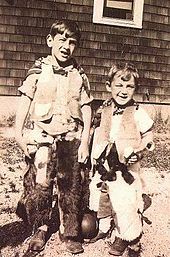

Early Life – A black and white photograph of two young children aged approximately six and three dressed as cowboys

Harvey (right) and his older brother Robert in 1934

Harvey (right) and his older brother Robert in 1934

Milk was born in Woodmere, New York, on Long Island, to William Milk and Minerva Karns. He was the younger son of Lithuanian Jewish parents and the grandson of Morris Milk, a department store owner who helped to organize the first synagogue in the area. As a child, Harvey was teased for his protruding ears, big nose, and oversized feet, and tended to grab attention as a class clown. He played football in school, and developed a passion for opera; in his teens, he acknowledged his homosexuality to himself, but kept it a closely guarded secret. Under his name in the high school yearbook, it read, “Glimpy Milk—and they say WOMEN are never at a loss for words.”

Milk graduated from Bay Shore High School in Bay Shore, New York, in 1947 and attended New York State College for Teachers in Albany (now the State University of New York at Albany) from 1947 to 1951, majoring in mathematics. He wrote for the college newspaper and earned a reputation as a gregarious, friendly student. None of his friends in high school or college suspected that he was gay. As one classmate remembered, “He was never thought of as a possible queer—that’s what you called them then—he was a man’s man.”

Early Career

After graduation, Milk joined the United States Navy during the Korean War. He served aboard the submarine rescue ship USS Kittiwake (ASR-13) as a diving officer. He later transferred to Naval Station, San Diego to serve as a diving instructor. In 1955, he was discharged from the Navy at the rank of lieutenant, junior grade. A color photograph of Milk in his Dinner Dress Blue Navy uniform

Milk dressed for his brother’s wedding in 1954

Milk dressed for his brother’s wedding in 1954

Milk’s early career was marked by frequent changes; in later years he would take delight in talking about his metamorphosis from a middle-class Jewish boy. He began teaching at George W. Hewlett High School on Long Island. In 1956, he met Joe Campbell, at the Jacob Riis Park beach, a popular location for gay men in Queens. Campbell was seven years younger than Milk, and Milk pursued him passionately. Even after they moved in together, Milk wrote Campbell romantic notes and poems. Growing bored with their New York lives, they decided to move to Dallas, Texas, but they were unhappy there and moved back to New York, where Milk got a job as an actuarial statistician at an insurance firm. Campbell and Milk separated after almost six years; it would be his longest relationship.

Milk tried to keep his early romantic life separate from his family and work. Once again bored and single in New York, he thought of moving to Miami to marry a lesbian friend to “have a front and each would not be in the way of the other.” However, he decided to remain in New York, where he secretly pursued gay relationships. In 1962 Milk became involved with Craig Rodwell, who was ten years younger. Though Milk courted Rodwell ardently, waking him every morning with a call and sending him notes, Milk was discouraged by Rodwell’s involvement with the New York Mattachine Society, a gay activist organization. When Rodwell was arrested for walking in Riis Park, and charged with inciting a riot and with indecent exposure (the law required men’s swimsuits to extend from above the navel to below the thigh), he spent three days in jail. The relationship soon ended as Milk became alarmed at Rodwell’s tendency to agitate the police.

Milk abruptly stopped working as an insurance actuary and became a researcher at the Wall Street firm Bache & Company. He was frequently promoted despite his tendency to offend the older members of the firm by ignoring their advice and flaunting his success. Although he was skilled at his job, co-workers sensed that Milk’s heart was not in his work. He started a romantic relationship with Jack Galen McKinley, and recruited him to work on conservative Republican Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign. Their relationship was troubled. When McKinley first began his relationship with Milk in late 1964, he was 16 years old, and therefore legally underage, though Milk recorded him as 18 in his address book. He was prone to depression and sometimes threatened to commit suicide if Milk did not show him enough attention. To make a point to McKinley, Milk took him to the hospital where Milk’s ex-lover, Joe Campbell, was himself recuperating from a suicide attempt, after his lover—a man named Billy Sipple—left him. Milk had remained friendly with Campbell, who had entered the avant-garde art scene in Greenwich Village, but Milk did not understand why Campbell’s despondency was sufficient cause to consider suicide as an option.

Rise of Castro Street

The Eureka Valley of San Francisco, where Market and Castro Streets intersect, had for decades been a blue-collar Irish Catholic neighborhood synonymous with the Most Holy Redeemer Parish (a few Lutherans of Scandinavian ancestry also lived in the neighborhood). Beginning in the late 1960’s, however, young families left the neighborhood and moved to Bay Area suburbs, and the city’s economic base eroded as factories moved to cheaper locations nearby and blue-collar port jobs relocated to Oakland. Mayor Joseph Alioto, proud of his working-class background and supporters, based his political career on welcoming developers to provide construction jobs and attracting a Roman Catholic Cardinal to the city. Many blue-collar workers—often Alioto supporters—lost their jobs as large corporations with service industry positions replaced factory and dry dock jobs. San Francisco, which had been “a city of villages,” a decentralized city with ethnic enclaves that each surrounded its own main street, began a demographic change.

The Eureka Valley of San Francisco, where Market and Castro Streets intersect, had for decades been a blue-collar Irish Catholic neighborhood synonymous with the Most Holy Redeemer Parish (a few Lutherans of Scandinavian ancestry also lived in the neighborhood). Beginning in the late 1960’s, however, young families left the neighborhood and moved to Bay Area suburbs, and the city’s economic base eroded as factories moved to cheaper locations nearby and blue-collar port jobs relocated to Oakland. Mayor Joseph Alioto, proud of his working-class background and supporters, based his political career on welcoming developers to provide construction jobs and attracting a Roman Catholic Cardinal to the city. Many blue-collar workers—often Alioto supporters—lost their jobs as large corporations with service industry positions replaced factory and dry dock jobs. San Francisco, which had been “a city of villages,” a decentralized city with ethnic enclaves that each surrounded its own main street, began a demographic change.

As the downtown area developed, neighborhoods suffered, including Castro Street. The Most Holy Redeemer Parish shops shut down, and houses were abandoned and shuttered. In 1963, real estate prices plummeted when most of the working-class families tried to sell their houses quickly after a gay bar opened in the neighborhood. Hippies, attracted to the free love ideals of the Haight-Ashbury area but repulsed by its crime rate, bought some of the cheap Victorian houses. Beginning in the late 1960’s, many San Francisco gays who were affluent began to move from the small apartments of the Polk Gulch area, San Francisco’s primary gayborhood since the end of World War II, to the large cheap Victorians in the Castro neighborhood.

Since the end of World War II, the major port city of San Francisco had been home to a sizable number of gay men expelled from the military who had decided to stay rather than return to their hometowns and face ostracism. By 1969 San Francisco had more gay people per capita than any other American city; when the National Institute of Mental Health asked the Kinsey Institute to survey homosexuals, the Institute chose San Francisco as its focus. Milk and McKinley were among the thousands of gay men attracted to San Francisco. McKinley was a stage manager for Tom O’Horgan, a director who started his career in experimental theater, but soon graduated to much larger Broadway productions. They arrived in 1969 with the Broadway touring company of Hair. McKinley was offered a job in the New York City production of Jesus Christ Superstar, and their tempestuous relationship came to an end. The city appealed to Milk so much that he decided to stay, working at an investment firm. In 1970, increasingly frustrated with the political climate after the U.S. invasion of Cambodia, Milk let his hair grow long. When told to cut it, he refused and was fired.

Milk drifted from California to Texas to New York, without a steady job or plan. In New York City he became involved with O’Horgan’s theater company as a “general aide,” signing on as associate producer for Lenny and for Eve Merriam’s Inner City. The time he had spent with the cast of flower children wore away much of Milk’s conservatism. A contemporary New York Times story about O’Horgan described Milk as “a sad eyed man—another aging hippie with long, long hair, wearing faded jeans and pretty beads.” Craig Rodwell read the description of the formerly uptight man and wondered if it could be the same person. One of Milk’s Wall Street friends worried that he seemed to have no plan or future, but remembered Milk’s attitude: “I think he was happier than at any time I had ever seen him in his entire life.”

Milk met Scott Smith, 18 years his junior, and began another relationship. Milk and Smith returned to San Francisco, where they lived on money they had saved. In March 1973, after a roll of film Milk left at a local shop was ruined, he and Smith opened a camera store on Castro Street with their last $1,000.

Changing Politics

In the late 1960’s, the Society for Individual Rights (SIR) and the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB) began to work against police persecution of gay bars and entrapment in San Francisco. Oral sex was still a felony, and in 1970, nearly 90 people in the city were arrested for it. Facing eviction if caught having homosexual sex in a rented apartment, and unwilling to face arrest in gay bars, some men turned to having sex in public parks at night. Mayor Alioto asked the police to target the parks, hoping the decision would appeal to the Archdiocese and his Catholic supporters. In 1971, 2,800 gay men were arrested for public sex in San Francisco. By comparison, New York City recorded only 63 arrests for the same offense that year. Any arrest for a morals charge required registration as a sex offender.

Congressman Phillip Burton, Assemblyman Willie Brown, and other California politicians recognized the growing clout and organization of homosexuals in the city, and courted their votes by attending meetings of gay and lesbian organizations. Brown pushed for legalization of sex between consenting adults in 1969 but failed. SIR was also pursued by popular moderate Supervisor Dianne Feinstein in her bid to become mayor, opposing Alioto. Ex-policeman Richard Hongisto worked for ten years to change the conservative views of the San Francisco Police Department, and also actively appealed to the gay community, which responded by raising significant funds for his campaign for sheriff. Though Feinstein was unsuccessful, Hongisto’s win in 1971 showed the political clout of the gay community.

SIR had become powerful enough for political maneuvering. In 1971 SIR members Jim Foster, Rick Stokes, and Advocate publisher David Goodstein formed the Alice B. Toklas Memorial Democratic Club, known as simply “Alice.” Alice befriended liberal politicians to persuade them to sponsor bills, proving successful in 1972 when Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon obtained Feinstein’s support for an ordinance outlawing employment discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. Alice chose Stokes to run for a relatively unimportant seat on the community college board. Though Stokes received 45,000 votes, he was quiet, unassuming, and did not win. Foster, however, shot to national prominence by being the first openly gay man to address a political convention. His speech at the 1972 Democratic National Convention ensured that his voice, according to San Francisco politicians, was the one to be heard when they wanted the opinions, and especially the votes, of the gay community.

Milk became more interested in political and civic matters when he was faced with civic problems and policies he disliked. One day in 1973, a state bureaucrat entered Milk’s shop Castro Camera and informed him that he owed $100 as a deposit against state sales tax. Milk was incredulous and traded shouts with the man about the rights of business owners; after he complained for weeks at state offices, the deposit was reduced to $30. Milk fumed about government priorities when a teacher came into his store to borrow a projector because the equipment in the schools did not function. Friends also remember around the same time having to restrain him from kicking the television while Attorney General John N. Mitchell gave consistent “I don’t recall” replies during the Watergate hearings. Milk decided that the time had come to run for city supervisor. He said later, “I finally reached the point where I knew I had to become involved or shut up.”

Campaigns

A color photograph of Milk with long hair and handlebar mustache with his arm around his sister-in-law, both smiling and standing in front of a storefront window showing a portion of a campaign poster with Milk’s photo and name

Milk, here with his sister-in-law in front of Castro Camera in 1973, had been changed by his experience with the counterculture of the 1960s. Dianne Feinstein, who first met him in 1973, did not recognize him when she met him again in 1978.

Milk, here with his sister-in-law in front of Castro Camera in 1973, had been changed by his experience with the counterculture of the 1960s. Dianne Feinstein, who first met him in 1973, did not recognize him when she met him again in 1978.

Milk’s reception by the gay political establishment in San Francisco was icy. Jim Foster, who had by then been active in gay politics for ten years, resented the newcomer’s asking for his endorsement for a position as prestigious as city supervisor. Foster told Milk, “There’s an old saying in the Democratic Party. You don’t get to dance unless you put up the chairs. I’ve never seen you put up the chairs.” Milk was furious at the patronizing snub, and the conversation marked the beginning of an antagonistic relationship between the “Alice” Club and Harvey Milk. Some gay bar owners, still battling police harassment and unhappy with what they saw as a timid approach by Alice to established authority in the city, decided to endorse him.

Though he had drifted through his life thus far, Milk found his vocation, according to journalist Frances FitzGerald, who called him a “born politician.” At first, his inexperience showed. He tried to do without money, support, or staff, and instead relied on his message of sound financial management, promoting individuals over large corporations and government. He supported the reorganization of supervisor elections from a city-wide ballot to district ballots, which was intended to reduce the influence of money and give neighborhoods more control over their representatives in city government. He also ran on a socially liberal platform, opposing government interference in private sexual matters and favoring the legalization of marijuana. Milk’s fiery, flamboyant speeches and savvy media skills earned him a significant amount of press during the 1973 election. He earned 16,900 votes—sweeping the Castro District and other liberal neighborhoods and coming in 10th place out of 32 candidates. Had the elections been reorganized to allow districts to elect their own supervisors, he would have won.

Mayor of Castro Street

Milk displayed an affinity for building coalitions from early in his political career. The Teamsters wanted to strike against beer distributors—Coors in particular — who refused to sign the union contract. An organizer asked Milk for assistance with gay bars; in return, Milk asked the union to hire more gay drivers. A few days later, Milk canvassed the gay bars in and surrounding the Castro District, urging them to refuse to sell the beer. With the help of a coalition of Arab and Chinese grocers the Teamsters had also recruited, the boycott was successful. Milk found a strong political ally in organized labor, and it was around this time that he began to style himself “The Mayor of Castro Street.” As Castro Street’s presence grew, so did Milk’s reputation. Tom O’Horgan remarked, “Harvey spent most of his life looking for a stage. On Castro Street he finally found it.”

Milk displayed an affinity for building coalitions from early in his political career. The Teamsters wanted to strike against beer distributors—Coors in particular — who refused to sign the union contract. An organizer asked Milk for assistance with gay bars; in return, Milk asked the union to hire more gay drivers. A few days later, Milk canvassed the gay bars in and surrounding the Castro District, urging them to refuse to sell the beer. With the help of a coalition of Arab and Chinese grocers the Teamsters had also recruited, the boycott was successful. Milk found a strong political ally in organized labor, and it was around this time that he began to style himself “The Mayor of Castro Street.” As Castro Street’s presence grew, so did Milk’s reputation. Tom O’Horgan remarked, “Harvey spent most of his life looking for a stage. On Castro Street he finally found it.”

Tensions between the older citizens of the Most Holy Redeemer Parish and the gays entering the Castro District were growing, however, and in 1973, when two gay men tried to open an antique shop, the Eureka Valley Merchants Association (EVMA) attempted to prevent them from receiving a business license. Milk and a few other gay business owners founded the Castro Village Association, with Milk as the president. He often repeated his philosophy that gays should buy from gay businesses. Milk organized the Castro Street Fair in 1974 to attract more customers to the area. More than 5,000 attended, and some of the EVMA members were stunned; they did more business at the Castro Street Fair than on any previous day.

Serious Candidate

Although he was a newcomer to the Castro District, Milk had shown leadership in the small community. He was starting to be taken seriously as a candidate and decided to run again for supervisor in 1975. He reconsidered his approach and cut his long hair, swore off marijuana, and vowed never to visit another gay bathhouse again. Milk’s campaigning earned the support of the teamsters, firefighters, and construction unions. Castro Camera became the center of activity in the neighborhood. Milk would often pull people off the street to work his campaigns for him—many discovered later that they just happened to be the type of men Milk found attractive.

Although he was a newcomer to the Castro District, Milk had shown leadership in the small community. He was starting to be taken seriously as a candidate and decided to run again for supervisor in 1975. He reconsidered his approach and cut his long hair, swore off marijuana, and vowed never to visit another gay bathhouse again. Milk’s campaigning earned the support of the teamsters, firefighters, and construction unions. Castro Camera became the center of activity in the neighborhood. Milk would often pull people off the street to work his campaigns for him—many discovered later that they just happened to be the type of men Milk found attractive.

Milk favored support for small businesses and the growth of neighborhoods. Since 1968, Mayor Alioto had been luring large corporations to the city despite what critics labeled “the Manhattanization of San Francisco.” As blue-collar jobs were replaced by the service industry, Alioto’s weakened political base allowed for new leadership to be voted into office in the city. George Moscone was elected mayor. Moscone had been instrumental in repealing the sodomy law earlier that year in the California State Legislature. He acknowledged Milk’s influence in his election by visiting Milk’s election night headquarters, thanking Milk personally, and offering him a position as a city commissioner. Milk came in seventh place in the election, only one position away from earning a supervisor seat. Liberal politicians held the offices of the mayor, district attorney, and sheriff.

Despite the new leadership in the city, there were still conservative strongholds. One of Moscone’s first acts as mayor was appointing a police chief to the embattled San Francisco Police Department (SFPD). He chose Charles Gain, against the wishes of the SFPD. Most of the force disliked Gain for criticizing the police in the press for racial insensitivity and alcohol abuse on the job, instead of working within the command structure to change attitudes. By request of the mayor, Gain made it clear that gay police officers would be welcomed in the department; this became national news. Police under Gain expressed their hatred of him, and of the mayor for betraying them.

Assassination – Moscone and Milk Assassinations

Assassination – Moscone and Milk Assassinations

On November 10, 1978, 10 months after being sworn in, White resigned his position on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, claiming that his annual salary of $9,600 was not enough to support his family. Milk was also feeling the pinch of the decrease in income when he and Scott Smith were forced to close Castro Camera a month before. Within days, White requested that his resignation be withdrawn and he be reinstated, and Mayor Moscone initially agreed. However, further consideration—and intervention by other supervisors—convinced the mayor to appoint someone more in line with the growing ethnic diversity of White’s district and the liberal leanings of the Board of Supervisors. On November 18, news broke of the murder of California Representative Leo Ryan, who was in Jonestown, Guyana to check on the remote community built by members of the Peoples Temple who had relocated from San Francisco. The next day came news of the mass suicide of members of the Peoples Temple. Horror came in degrees as San Franciscans learned more than 400 Jonestown residents were dead. Dan White remarked to two aides who were working for his reinstatement, “You see that? One day I’m on the front page and the next I’m swept right off.” Soon the number of dead in Guyana topped 900.

Moscone planned to announce White’s replacement days later, on November 27, 1978. A half hour before the press conference, White entered City Hall through a basement window to avoid metal detectors, and made his way to Moscone’s office. Witnesses heard shouting between White and Moscone, then gunshots. White shot the mayor in the shoulder and chest, then twice in the head after Moscone had fallen on the floor. White then quickly walked to his former office, reloading his police-issue revolver with hollow-point bullets along the way, and intercepted Milk, asking him to step inside for a moment. Dianne Feinstein heard gunshots and called the police. She found Milk face down on the floor, shot five times, including twice in the head at close range. After identifying both bodies, Feinstein was shaking so badly she required support from the police chief. It was she who announced to the press, “Today San Francisco has experienced a double tragedy of immense proportions. As President of the Board of Supervisors, it is my duty to inform you that both Mayor Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk have been shot and killed,” then adding after being drowned out by shouts of disbelief, “and the suspect is Supervisor Dan White.” Milk was 48 years old. Moscone was 49.

Within an hour, White called his wife from a nearby diner; she met him at a church and escorted him to the police, where White turned himself in. Many residents left flowers on the steps of City Hall. That evening, a spontaneous gathering began to form on Castro Street, moving toward City Hall in a candlelight vigil. Their numbers were estimated between 25,000 and 40,000, spanning the width of Market Street, extending the mile and a half (2.4 km) from Castro Street. The next day, the bodies of Moscone and Milk were brought to the City Hall rotunda where mourners paid their respects. Six thousand mourners attended a service for Mayor Moscone at St. Mary’s Cathedral. Two memorials were held for Milk; a small one at Temple Emanu-El and a more boisterous one at the Opera House.

“City in agony”

A reproduction of the top front page of the San Francisco Examiner on November 28, 1978. At the top is a black banner with white lettering reading “A city in agony: Full story of the City Hall murders.” Below that the large headline reads “White Charged—Faces Death,” then the banner of the name of the newspaper

The headline of The San Francisco Examiner on November 28, 1978 announced Dan White was charged with first-degree murder, and eligible for the death penalty.

The headline of The San Francisco Examiner on November 28, 1978 announced Dan White was charged with first-degree murder, and eligible for the death penalty.

Moscone had recently increased security at City Hall in the wake of the Jonestown suicides. Survivors from Guyana recounted drills for suicide preparations that Jones called “White Nights.” Rumors about Moscone’s and Milk’s murders were fueled by the coincidence of Dan White’s name and Jones’ suicide preparations. A stunned District Attorney called the assassinations so close to the news about Jonestown “incomprehensible,” but denied any connection. Governor Jerry Brown ordered all flags in California to be flown at half staff, and called Milk a “hard-working and dedicated supervisor, a leader of San Francisco’s gay community, who kept his promise to represent all his constituents.” President Jimmy Carter expressed his shock at both murders and sent his condolences. Speaker of the California Assembly Leo McCarthy called it “an insane tragedy.” “A City in Agony” topped the headlines in The San Francisco Examiner the day after the murders; inside the paper stories of the assassinations under the headline “Black Monday” were printed back to back with updates of bodies being shipped home from Guyana. An editorial describing “A city with more sadness and despair in its heart than any city should have to bear” went on to ask how such tragedies could occur, particularly to “men of such warmth and vision and great energies.” Dan White was charged with two counts of murder and held without bail, eligible for the death penalty owing to the recent passage of a statewide proposition that allowed death or life in prison for the murder of a public official. One analysis of the months surrounding the murders called 1978 and 1979 “the most emotionally devastating years in San Francisco’s fabulously spotted history.”

The 32-year-old White, who had been in the Army during the Vietnam War, had run on a tough anti-crime platform in his district. Colleagues declared him a high-achieving “all-American boy.” He was to have received an award the next week for rescuing a woman and child from a 17-story burning building when he was a firefighter in 1977. Though he was the only supervisor to vote against Milk’s gay rights ordinance earlier that year, he had been quoted as saying, “I respect the rights of all people, including gays.” Milk and White at first got along well. One of White’s political aides (who was gay) remembered, “Dan had more in common with Harvey than he did with anyone else on the board.” White had voted to support a center for gay seniors, and to honor Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin’s 25th anniversary and pioneering work.

“The plaque covering Milk’s ashes reads, in part: [Harvey Milk’s] camera store and campaign headquarters at 575 Castro Street and his apartment upstairs were centers of community activism for a wide range of human rights, environmental, labor, and neighborhood issues. Harvey Milk’s hard work and accomplishments on behalf of all San Franciscans earned him widespread respect and support. His life is an inspiration to all people committed to equal opportunity and an end to bigotry.”

After Milk’s vote for the mental health facility in White’s district, however, White refused to speak with Milk and only communicated with one of Milk’s aides. Other acquaintances remembered White as very intense. “He was impulsive … He was an extremely competitive man, obsessively so … I think he could not take defeat,” San Francisco’s assistant fire chief told reporters. White’s first campaign manager quit in the middle of the campaign, and told a reporter that White was an egotist and it was clear that he was antigay, though he denied it in the press. White’s associates and supporters described him “as a man with a pugilistic temper and an impressive capacity for nurturing a grudge.” The aide who had handled communications between White and Milk remembered, “Talking to him, I realized that he saw Harvey Milk and George Moscone as representing all that was wrong with the world.”

When Milk’s friends looked in his closet for a suit for his casket, they learned how much he had been affected by the recent decrease in his income as a supervisor. All of his clothes were coming apart; all of his socks had holes. He was cremated and his ashes were split, most of them scattered in San Francisco Bay by his closest friends. Some of them were encapsulated and buried beneath the sidewalk in front of 575 Castro Street, where Castro Camera had been located. Harry Britt, one of four people Milk listed on his tape as an acceptable replacement should he be assassinated, was chosen to fill that position by the city’s acting mayor, Dianne Feinstein.

Trial – Further information: Dan White and Twinkie defense

Dan White’s arrest and trial caused a sensation, and illustrated severe tensions between the liberal population and the city police. The San Francisco Police were mostly working-class Irish descendants who intensely disliked the growing gay immigration, as well as the liberal direction of the city government. After White turned himself in and confessed, he sat in his cell while his former colleagues on the police force told Harvey Milk jokes; police openly wore “Free Dan White” T-shirts in the days after the murder. An undersheriff for San Francisco later stated: “The more I observed what went on at the jail, the more I began to stop seeing what Dan White did as the act of an individual and began to see it as a political act in a political movement.” White showed no remorse for his actions, and only exhibited vulnerability during an eight-minute call to his mother from jail.

The seated jury for White’s trial consisted of white middle-class San Franciscans who were mostly Catholic; gays and ethnic minorities were excused from the jury pool. The jury was clearly sympathetic to the defendant: some of the members cried when they heard White’s tearful recorded confession, at the end of which the interrogator thanked White for his honesty. White’s defense attorney, Doug Schmidt, argued that he was not responsible for his actions, using the legal defense known as diminished capacity: “Good people, fine people, with fine backgrounds, simply don’t kill people in cold blood.” Schmidt tried to prove that White’s anguished mental state was a result of manipulation by the politicos in City Hall who had consistently disappointed and confounded him, finally promising to give his job back only to refuse him again. Schmidt said that White’s mental deterioration was demonstrated and exacerbated by his junk food binge the night before the murders, since he was usually known to have been health-food conscious. Area newspapers quickly dubbed it the Twinkie defense. White was acquitted of the first degree murder charge on May 21, 1979, but found guilty of voluntary manslaughter of both victims, and he was sentenced to serve seven and two-thirds years. With the sentence reduced for time served and good behavior, he would be released in five. He cried when he heard the verdict.