Happy Birthday Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

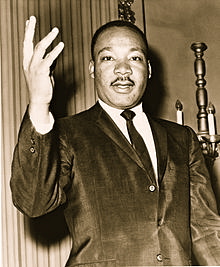

Martin Luther King, Jr.

A short biography of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. He is widely considered the most influential leader of the American civil rights movement. He fought to overturn Jim Crow segregation laws and eliminate social and economic differences between blacks and whites. King’s speeches and famous quotes continue to inspire millions today.

Martin Luther King, Jr., (born January 15, 1929 – died April 4, 1968) was an American pastor, activist, humanitarian, and leader in the African-American Civil Rights Movement. He is best known for his role in the advancement of civil rights using nonviolent civil disobedience based on his Christian beliefs.

He was born Michael King, but his father changed his name in honor of the German reformer Martin Luther. A Baptist minister, King became a civil rights activist early in his career. He led the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott and helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1957, serving as its first president. With the SCLC, King led an unsuccessful struggle against segregation in Albany, Georgia, in 1962, and organized nonviolent protests in Birmingham, Alabama, that attracted national attention following television news coverage of the brutal police response. King also helped to organize the 1963 March on Washington, where he delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. There, he established his reputation as one of the greatest orators in American history.

On October 14, 1964, King received the Nobel Peace Prize for combating racial inequality through nonviolence. In 1965, he and the SCLC helped to organize the Selma to Montgomery marches and the following year, he took the movement north to Chicago to work on segregated housing. In the final years of his life, King expanded his focus to include poverty and speak against the Vietnam War, alienating many of his liberal allies with a 1967 speech titled “Beyond Vietnam.”

In 1968, King was planning a national occupation of Washington, D.C., to be called the Poor People’s Campaign, when he was assassinated on April 4 in Memphis, Tennessee. His death was followed by riots in many U.S. cities. Allegations that James Earl Ray, the man convicted of killing King, had been framed or acted in concert with government agents persisted for decades after the shooting. The jury of a 1999 civil trial found Loyd Jowers to be complicit in a conspiracy against King. The ruling has since been discredited and a sister of Jowers admitted that he had fabricated the story so he could make $300,000 from selling the story, and she in turn corroborated his story in order to get some money to pay her income tax.

In 1968, King was planning a national occupation of Washington, D.C., to be called the Poor People’s Campaign, when he was assassinated on April 4 in Memphis, Tennessee. His death was followed by riots in many U.S. cities. Allegations that James Earl Ray, the man convicted of killing King, had been framed or acted in concert with government agents persisted for decades after the shooting. The jury of a 1999 civil trial found Loyd Jowers to be complicit in a conspiracy against King. The ruling has since been discredited and a sister of Jowers admitted that he had fabricated the story so he could make $300,000 from selling the story, and she in turn corroborated his story in order to get some money to pay her income tax.

King was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Congressional Gold Medal. Martin Luther King, Jr. Day was established as a holiday in numerous cities and states beginning in 1971, and as a U.S. federal holiday in 1986. Hundreds of streets in the U.S. have been renamed in his honor. In addition, a county was rededicated in his honor. A memorial statue on the National Mall was opened to the public in 2011.

Early life and Education

King’s high school alma mater was named after African-American scholar Booker T. Washington

Martin Luther King, Jr., was born on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia, to Reverend Martin Luther King, Sr. and Alberta Williams King. His legal name at birth was Michael King. King’s father was also born Michael King. The father changed his and his son’s names following a 1934 trip to Germany to attend the Fifth Baptist World Alliance Congress in Berlin. It was during this time he chose to be called Martin Luther King in honor of the German reformer Martin Luther. King had Irish ancestry through his paternal great-grandfather.

Martin, Jr., was a middle child, between an older sister, Willie Christine King, and a younger brother, Alfred Daniel Williams King. King sang with his church choir at the 1939 Atlanta premiere of the movie Gone with the Wind. King liked singing and music. King’s mother, an accomplished organist and choir leader, took him to various churches to sing. He received attention for singing “I Want to Be More and More Like Jesus.” King later became a member of the junior choir in his church.

King said his father regularly whipped him until he was fifteen and a neighbor reported hearing the elder King telling his son “he would make something of him even if he had to beat him to death.” King saw his father’s proud and unafraid protests in relation to segregation, such as Martin, Sr. refusing to listen to a traffic policeman after being referred to as “boy” or stalking out of a store with his son when being told by a shoe clerk that they would have to move to the rear to be served.

When King was a child, he befriended a white boy whose father owned a business near his family’s home. When the boys were 6, they attended different schools, with King attending a segregated school for African-Americans. King then lost his friend because the child’s father no longer wanted them to play together.

King suffered from depression throughout much of his life. In his adolescent years, he initially felt some resentment against whites due to the “racial humiliation” that he, his family, and his neighbors often had to endure in the segregated South. At age 12, shortly after his maternal grandmother died, King blamed himself and jumped out of a second story window, but survived.

King was originally skeptical of many of Christianity’s claims. At the age of thirteen, he denied the bodily resurrection of Jesus during Sunday school. From this point, he stated, “doubts began to spring forth unrelentingly.” However, he later concluded that the Bible has “many profound truths which one cannot escape” and decided to enter the seminary.

Growing up in Atlanta, King attended Booker T. Washington High School. He became known for his public speaking ability and was part of the school’s debate team. King became the youngest assistant manager of a newspaper delivery station for the Atlanta Journal in 1942 at age 13. During his junior year, he won first prize in an oratorical contest sponsored by the Negro Elks Club in Dublin, Georgia. Returning home to Atlanta by bus, he and his teacher were ordered by the driver to stand so white passengers could sit down. King refused initially, but complied after his teacher informed him that he would be breaking the law if he did not go along with the order. He later characterized this incident as “the angriest I have ever been in my life.” A precocious student, he skipped both the ninth and the twelfth grades of high school. It was during King’s junior year that Morehouse College announced it would accept any high school juniors who could pass its entrance exam. At that time, most of the students had abandoned their studies to participate in World War II. Due to this, the school became desperate to fill in classrooms. At age 15, King passed the exam and entered Morehouse. The summer before his last year at Morehouse, in 1947, an eighteen-year old King made the choice to enter the ministry after he concluded the church offered the most assuring way to answer “an inner urge to serve humanity”. King’s “inner urge” had begun developing and he made peace with the Baptist Church, as he believed he would be a “rational” minister with sermons that were “a respectful force for ideas, even social protest.”

Growing up in Atlanta, King attended Booker T. Washington High School. He became known for his public speaking ability and was part of the school’s debate team. King became the youngest assistant manager of a newspaper delivery station for the Atlanta Journal in 1942 at age 13. During his junior year, he won first prize in an oratorical contest sponsored by the Negro Elks Club in Dublin, Georgia. Returning home to Atlanta by bus, he and his teacher were ordered by the driver to stand so white passengers could sit down. King refused initially, but complied after his teacher informed him that he would be breaking the law if he did not go along with the order. He later characterized this incident as “the angriest I have ever been in my life.” A precocious student, he skipped both the ninth and the twelfth grades of high school. It was during King’s junior year that Morehouse College announced it would accept any high school juniors who could pass its entrance exam. At that time, most of the students had abandoned their studies to participate in World War II. Due to this, the school became desperate to fill in classrooms. At age 15, King passed the exam and entered Morehouse. The summer before his last year at Morehouse, in 1947, an eighteen-year old King made the choice to enter the ministry after he concluded the church offered the most assuring way to answer “an inner urge to serve humanity”. King’s “inner urge” had begun developing and he made peace with the Baptist Church, as he believed he would be a “rational” minister with sermons that were “a respectful force for ideas, even social protest.”

In 1948, he graduated from Morehouse with a B.A. degree in sociology, and enrolled in Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, from which he graduated with a B.Div. degree in 1951. King’s father fully supported his decision to continue his education. King was joined in attending Crozer by Walter McCall, a former classmate at Morehouse. At Crozer, King was elected president of the student body. The African-American students of Crozer for the most part conducted their social activity on Edwards Street. King was endeared to the street due to a classmate having an aunt that prepared the two collard greens, which they both relished. King once called out a student for keeping beer in his room because of their shared responsibility as African-Americans to bear “the burdens of the Negro race.” For a time, he was interested in Walter Rauschenbusch’s “social gospel.” In his third year there, he became romantically involved with the daughter of an immigrant German woman working as a cook in the cafeteria. The daughter had been involved with a professor prior to her relationship with King. King had plans of marrying her, but was advised not to by friends due to the reaction an interracial relationship would spark from both blacks and whites, as well as the chances of it destroying his chances of ever pastoring a church in the South. King tearfully told a friend that he could not endure his mother’s pain over the marriage and broke the relationship off around six months later. He would continue to have lingering feelings, with one friend being quoted as saying, “He never recovered.”They should be taken only in extreme cases. Learn about it at .

King married Coretta Scott, on June 18, 1953, on the lawn of her parents’ house in her hometown of Heiberger, Alabama. They became the parents of four children: Yolanda King, Martin Luther King III, Dexter Scott King, and Bernice King. During their marriage, King limited Coretta’s role in the civil rights movement and expected her to be a housewife.

Doctoral Studies

Martin Luther King, Jr. authorship issues

King then began doctoral studies in systematic theology at Boston University and received his Ph.D. degree on June 5, 1955, with a dissertation on “A Comparison of the Conceptions of God in the Thinking of Paul Tillich and Henry Nelson Wieman.” An academic inquiry concluded in October 1991 that portions of his dissertation had been plagiarized and he had acted improperly. However, “despite its finding, the committee said that ‘no thought should be given to the revocation of Dr. King’s doctoral degree,’ an action that the panel said would serve no purpose.” The committee also found that the dissertation still “makes an intelligent contribution to scholarship.” However, a letter is now attached to King’s dissertation in the university library, noting that numerous passages were included without the appropriate quotations and citations of sources.

Ideas, influences, and Political Stances – Religion

King became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, when he was twenty-five years old, in 1954. As a Christian minister, his main influence was Jesus Christ and the Christian gospels, which he would almost always quote in his religious meetings, speeches at church, and in public discourses. King’s faith was strongly based in Jesus’ commandment of loving your neighbor as yourself, loving God above all, and loving your enemies, praying for them and blessing them. His non-violent thought was also based in the injuction to turn the other cheek in the Sermon on the Mount, and Jesus’ teaching of putting the sword back into its place (Matthew 26:52). In his famous Letter from Birmingham Jail, King urged action consistent with what he describes as Jesus’ “extremist” love, and also quoted numerous other Christian pacifist authors, which was very usual for him. In another sermon, he stated:

King became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, when he was twenty-five years old, in 1954. As a Christian minister, his main influence was Jesus Christ and the Christian gospels, which he would almost always quote in his religious meetings, speeches at church, and in public discourses. King’s faith was strongly based in Jesus’ commandment of loving your neighbor as yourself, loving God above all, and loving your enemies, praying for them and blessing them. His non-violent thought was also based in the injuction to turn the other cheek in the Sermon on the Mount, and Jesus’ teaching of putting the sword back into its place (Matthew 26:52). In his famous Letter from Birmingham Jail, King urged action consistent with what he describes as Jesus’ “extremist” love, and also quoted numerous other Christian pacifist authors, which was very usual for him. In another sermon, he stated:

“Before I was a civil rights leader, I was a preacher of the Gospel. This was my first calling and it still remains my greatest commitment. You know, actually all that I do in civil rights I do because I consider it a part of my ministry. I have no other ambitions in life but to achieve excellence in the Christian ministry. I don’t plan to run for any political office. I don’t plan to do anything but remain a preacher. And what I’m doing in this struggle, along with many others, grows out of my feeling that the preacher must be concerned about the whole man.”

—King, 1967

In his speech “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop”, he stated that he just wanted to do God’s will.

Non-Violence

King at a Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C.

King at a Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C.

Veteran African-American civil rights activist Bayard Rustin served as King’s main advisor and mentor in the late 1950s. Rustin came from the Christian pacifist tradition; he had also studied Gandhi’s teachings and applied them with the Journey of Reconciliation campaign in the 1940s. King had initially known little about Gandhi and rarely used the term “nonviolence” during his early years of activism in the early 1950’s. King also believed in and practiced self-defense, even obtaining guns in his household as a means of defense against possible attackers. Rustin guided King by showing him the alternative of nonviolent resistance, arguing that this would be a better means to accomplish his goals of civil rights than self-defense. Rustin counseled King to dedicate himself to the principles of non-violence.

Inspired by Mahatma Gandhi’s success with non-violent activism, King had “for a long time…wanted to take a trip to India.” With assistance from the Quaker group the American Friends Service Committee, he was able to make the journey in April 1959. The trip to India affected King, deepening his understanding of non-violent resistance and his commitment to America’s struggle for civil rights. In a radio address made during his final evening in India, King reflected, “Since being in India, I am more convinced than ever before that the method of nonviolent resistance is the most potent weapon available to oppressed people in their struggle for justice and human dignity.”

Bayard Rustin’s open homosexuality, support of democratic socialism, and his former ties to the Communist Party USA caused many white and African-American leaders to demand King distance himself from Rustin, which King agreed to do. However, King agreed that Rustin should be one of the main organizers of the 1963 March on Washington.

King’s admiration of Gandhi’s non-violence did not diminish in later years. He went so far as to hold up his example when receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, hailing the “successful precedent” of using non-violence “in a magnificent way by Mohandas K. Gandhi to challenge the might of the British Empire… He struggled only with the weapons of truth, soul force, non-injury and courage.”

Gandhi seemed to have influenced him with certain moral principles, though Gandhi himself had been influenced by The Kingdom of God Is Within You, a nonviolent classic written by Christian anarchist Leo Tolstoy. In turn, both Gandhi and Martin Luther King had read Tolstoy, and King, Gandhi and Tolstoy had been strongly influenced by Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount. King quoted Tolstoy’s War and Peace in 1959.

Another influence for King’s non-violent method was Thoreau’s essay On Civil Disobedience, which King read in his student days. He was influenced by the idea of refusing to cooperate with an evil system. He also was greatly influenced by the works of Protestant theologians Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich, as well as Walter Rauschenbusch’s Christianity and the Social Crisis. King also sometimes used the concept of “agape” (brotherly Christian love). However, after 1960, he ceased employing it in his writings.

Politics

As the leader of the SCLC, King maintained a policy of not publicly endorsing a U.S. political party or candidate: “I feel someone must remain in the position of non-alignment, so that he can look objectively at both parties and be the conscience of both—not the servant or master of either.” In a 1958 interview, he expressed his view that neither party was perfect, saying, “I don’t think the Republican party is a party full of the almighty God nor is the Democratic party. They both have weaknesses … And I’m not inextricably bound to either party.”

King critiqued both parties’ performance on promoting racial equality:

Actually, the Negro has been betrayed by both the Republican and the Democratic party. The Democrats have betrayed him by capitulating to the whims and caprices of the Southern Dixiecrats. The Republicans have betrayed him by capitulating to the blatant hypocrisy of reactionary right wing northern Republicans. And this coalition of southern Dixiecrats and right wing reactionary northern Republicans defeats every bill and every move towards liberal legislation in the area of civil rights.

Although King never publicly supported a political party or candidate for president, in a letter to a civil rights supporter in October 1956 he said that he was undecided as to whether he would vote for Adlai Stevenson or Dwight Eisenhower, but that “In the past I always voted the Democratic ticket.” In his autobiography, King says that in 1960 he privately voted for Democratic candidate John F. Kennedy: “I felt that Kennedy would make the best president. I never came out with an endorsement. My father did, but I never made one.” King adds that he likely would have made an exception to his non-endorsement policy for a second Kennedy term, saying “Had President Kennedy lived, I would probably have endorsed him in 1964.” King supported the ideals of democratic socialism, although he was reluctant to speak directly of this support due to the anti-communist sentiment being projected throughout America at the time, and the association of socialism with communism. King believed that capitalism could not adequately provide the basic necessities of many American people, particularly the African American community.

Compensation

King stated that black Americans, as well as other disadvantaged Americans, should be compensated for historical wrongs. In an interview conducted for Playboy in 1965, he said that granting black Americans only equality could not realistically close the economic gap between them and whites. King said that he did not seek a full restitution of wages lost to slavery, which he believed impossible, but proposed a government compensatory program of $50 billion over ten years to all disadvantaged groups.

He posited that “the money spent would be more than amply justified by the benefits that would accrue to the nation through a spectacular decline in school dropouts, family breakups, crime rates, illegitimacy, swollen relief rolls, rioting and other social evils.” He presented this idea as an application of the common law regarding settlement of unpaid labor, but clarified that he felt that the money should not be spent exclusively on blacks. He stated, “It should benefit the disadvantaged of all races.”

The lack of attention given to family planning

On being awarded the Planned Parenthood Federation of America’s Margaret Sanger Award on 5th May, 1966, King said:

“Recently, the press has been filled with reports of sightings of flying saucers. While we need not give credence to these stories, they allow our imagination to speculate on how visitors from outer space would judge us. I am afraid they would be stupefied at our conduct. They would observe that for death planning we spend billions to create engines and strategies for war. They would also observe that we spend millions to prevent death by disease and other causes. Finally they would observe that we spend paltry sums for population planning, even though its spontaneous growth is an urgent threat to life on our planet. Our visitors from outer space could be forgiven if they reported home that our planet is inhabited by a race of insane men whose future is bleak and uncertain.”

There is no human circumstance more tragic than the persisting existence of a harmful condition for which a remedy is readily available. Family planning, to relate population to world resources, is possible, practical and necessary. Unlike plagues of the dark ages or contemporary diseases we do not yet understand, the modern plague of overpopulation is soluble by means we have discovered and with resources we possess. What is lacking is not sufficient knowledge of the solution but universal consciousness of the gravity of the problem and education of the billions who are its victims. …

Montgomery Bus Boycott, 1955

Main articles: Montgomery Bus Boycott and Jim Crow laws § Public arena

In March 1955, a fifteen-year-old school girl in Montgomery, Claudette Colvin, refused to give up her bus seat to a white man in compliance with Jim Crow laws, laws in the US South that enforced racial segregation. King was on the committee from the Birmingham African-American community that looked into the case; because Colvin was pregnant and unmarried, E.D. Nixon and Clifford Durr decided to wait for a better case to pursue.

On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat. The Montgomery Bus Boycott, urged and planned by Nixon and led by King, soon followed. The boycott lasted for 385 days, and the situation became so tense that King’s house was bombed. King was arrested during this campaign, which concluded with a United States District Court ruling in Browder v. Gayle that ended racial segregation on all Montgomery public buses. King’s role in the bus boycott transformed him into a national figure and the best-known spokesman of the civil rights movement.

Southern Christian Leadership Conference

In 1957, King, Ralph Abernathy, Fred Shuttlesworth, Joseph Lowery, and other civil rights activists founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The group was created to harness the moral authority and organizing power of black churches to conduct non-violent protests in the service of civil rights reform. King led the SCLC until his death.

On September 20, 1958, while signing copies of his book Stride Toward Freedom in Blumstein’s department store in Harlem, King narrowly escaped death when Izola Curry, a mentally ill black woman who believed he was conspiring against her with communists, stabbed him in the chest with a letter opener. After emergency surgery, King was hospitalized for several weeks, while Curry was found mentally incompetent to stand trial. In 1959, he published a short book called The Measure of A Man, which contained his sermons “What is Man?” and “The Dimensions of a Complete Life.” The sermons argued for man’s need for God’s love and criticized the racial injustices of Western civilization.

Harry Wachtel—who joined King’s legal advisor Clarence B. Jones in defending four ministers of the SCLC in a libel suit over a newspaper advertisement (New York Times Co. v. Sullivan)—founded a tax-exempt fund to cover the expenses of the suit and to assist the nonviolent civil rights movement through a more effective means of fundraising. This organization was named the “Gandhi Society for Human Rights”. King served as honorary president for the group. Displeased with the pace of President Kennedy’s addressing the issue of segregation, King and the Gandhi Society produced a document in 1962 calling on the President to follow in the footsteps of Abraham Lincoln and use an Executive Order to deliver a blow for Civil Rights as a kind of Second Emancipation Proclamation – Kennedy did not execute the order.

Lyndon Johnson and Robert Kennedy with Civil Rights leaders, June 22, 1963

Lyndon Johnson and Robert Kennedy with Civil Rights leaders, June 22, 1963

The FBI, under written directive from Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, began tapping King’s telephone in the fall of 1963. Concerned that allegations of communists in the SCLC, if made public, would derail the administration’s civil rights initiatives, Kennedy warned King to discontinue the suspect associations, and later felt compelled to issue the written directive authorizing the FBI to wiretap King and other SCLC leaders. J. Edgar Hoover feared Communists were trying to infiltrate the Civil Rights movement, but when no such evidence emerged, the bureau used the incidental details caught on tape over the next five years in attempts to force King out of the preeminent leadership position.

King believed that organized, nonviolent protest against the system of southern segregation known as Jim Crow laws would lead to extensive media coverage of the struggle for black equality and voting rights. Journalistic accounts and televised footage of the daily deprivation and indignities suffered by southern blacks, and of segregationist violence and harassment of civil rights workers and marchers, produced a wave of sympathetic public opinion that convinced the majority of Americans that the Civil Rights Movement was the most important issue in American politics in the early 1960’s.

King organized and led marches for blacks’ right to vote, desegregation, labor rights and other basic civil rights. The SCLC’s 1957 Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom was the first time King addressed a national audience. Most of these rights were successfully enacted into the law of the United States with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

King and the SCLC put into practice many of the principles of the Christian Left and applied the tactics of nonviolent protest with great success by strategically choosing the method of protest and the places in which protests were carried out. There were often dramatic stand-offs with segregationist authorities. Sometimes these confrontations turned violent.

King and the SCLC put into practice many of the principles of the Christian Left and applied the tactics of nonviolent protest with great success by strategically choosing the method of protest and the places in which protests were carried out. There were often dramatic stand-offs with segregationist authorities. Sometimes these confrontations turned violent.

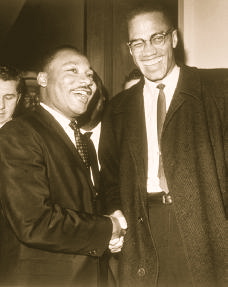

Throughout his participation in the civil rights movement, King was criticized by many groups. This included opposition by more militant blacks such as Nation of Islam member Malcolm X. Stokely Carmichael was a separatist and disagreed with King’s plea for racial integration because he considered it an insult to a uniquely African-American culture. Omali Yeshitela urged Africans to remember the history of violent European colonization and how power was not secured by Europeans through integration, but by violence and force.