English Country Dance

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_country_dance

English Country Dance Documentary

A very brief introduction to English country dancing. For more information about this lively form of folk dance, please visit: www.englishcountrydancing.net.

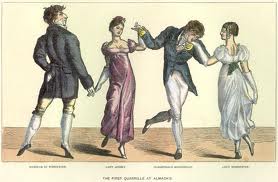

English Country Dance is a form of social folk dance which originated in Renaissance England, and was popular until the early 19th century in parts of Europe, the American colonies and the United States. It is the ancestor of several other folk dances, including contra and square dance. English country dance was revived in the early 20th century as a part of the larger English folk revival, and is practiced today primarily in North America and Britain. In Britain, this form is often referred to as “Playford,” while “country dance” is applied to a range of English folk dances.

English Country Dance is a form of social folk dance which originated in Renaissance England, and was popular until the early 19th century in parts of Europe, the American colonies and the United States. It is the ancestor of several other folk dances, including contra and square dance. English country dance was revived in the early 20th century as a part of the larger English folk revival, and is practiced today primarily in North America and Britain. In Britain, this form is often referred to as “Playford,” while “country dance” is applied to a range of English folk dances.

Form

The choreography dictates the interactions between partners and between couples in a set. A set is a group of couples, most commonly two or three, but sometimes four, that interact during a single progression. Rarely, dances call for five or six couples in a set. Most commonly, English country dances are longways and progressive. Multiple sets of couples form two long lines, along which couples travel at the end of each iteration of figures, meeting new couples and repeating the series of figures many times. Alternately, dances can be finite, a set forming an independent unit within which the series of figures are repeated a limited number of times. These dances are often non-progressive, each couple retaining their original positions in decades they are performed.

The origins of English country dance are a matter of some debate. Shared features with other English folk dances, such as morris and sword dancing, suggest a true ‘country’ origin; however, other aspects resemble the courtly dances of Continental Europe, especially those of Renaissance Italy. It is probable that English country dance is the result of some synthesis of these dance forms. While many references to ‘country dancing’ and titles shared with known 17th-century dances appear from the reign of Elizabeth I forward, few of these can conclusively be demonstrated to refer to English country dance. Little of substance, therefore, is positively known of the form before the mid-17th century.

Published instructions for English country dances first appear in The English Dancing Master of 1651, issued by John Playford, aLondon music publisher. These dances, like most dances of the period, are unattributed. Playford and his successors had a practical monopoly on the publication of dance manuals until 1711, and ceased publishing around 1728. During this period, English country dances took a variety of forms, including finite sets for two, three and four couples as well as circles and squares. By the 1720s, these had been almost entirely supplanted by longways sets for three and two couples, which would remain normative until English country dance’s eclipse.

English country dance traveled outside Britain, and enjoyed particular popularity in France. André Lorin visited the English court in the late 17th century and after returning to France he presented a manuscript of dances in the English manner to Louis XIV. In 1706 Raoul Auger Feuillet published his Recüeil de Contredances, a collection of “contredanse anglais” presented in a simplified form of Beauchamp-Feuillet notation and including some dances invented by the author as well as authentic English dances. This was subsequently translated into English by John Essex and published in England as For the Further Improvement of Dancing. Copies of these books may be found online.

By the early 19th century, new dance forms from the Continent had begun to reach England and America. As the quadrille and waltz became increasingly popular, English country dance declined, and by 1830 had almost entirely vanished from society ballrooms.

In the early 20th century, historical English country dances were revived in England, first by suffragist Mary Neal, but most famously by folklorist Cecil Sharp, who also reintroduced English country dance to the United States. The English country dance revivalists were obliged to reconstruct the historical dances, as no source clearly defined the historical dance terms. Sharp’s definitions of English country dance figures became the standard interpretation, with certain exceptions. Sharp and the other revivalists of the early 20th century were wholly concerned with reconstructing and teaching dances from the historical dance manuals. It was not until the 1930’s that the first new English country dances were composed. The publication of Maggot Pie, the first collection of modern English country dances, in 1932 was controversial in the English country dance community; only in the late 20th century did modern compositions become fully accepted. Reconstructions of historical dances and new compositions continue to be produced and danced today. Interpreters and composers of the 20th century include Douglas and Helen Kennedy, Pat Shaw, Tom Cook, Ken Sheffield, Charles Bolton, Michael Barraclough, Colin Hume, Gary Roodman, and Andrew Shaw.

English country dance was the progenitor of several other dance forms. The French contredanse, arriving independently in the American colonies, became the New England contra dance, which also experienced a resurgence in the mid-20th century. The French expression of English country dance may also have contributed to the development of the quadrille, though this is debated. The square-eight form of English country dance had fallen from favour by the time the French received it, and the earliest French works contain only the longways form. The quadrille evolved into square dance in the United States, while in Ireland, it contributed to the development of modern Irish dance. English country dance in Scotland developed its own flavour and became the separate Scottish country dance. English Ceilidh is a special case, being a convergence of English, Irish and Scottish forms. In addition, certain English country dances survived independently in the popular repertoire. One such is the Virginia Reel, which is almost exactly the same as the English country dance ‘Sir Roger de Coverly’. English country dance can therefore be seen as the ancestor of a whole family of social folk dances in the Anglosphere.

Some (modern) English Country Dance terms

Some (modern) English Country Dance terms

Active Couple – for long-ways sets with more than one couple dancing, the active couple is the couple doing the more complicated movement during any given portion of the dance. For duple dances, that is every other couple, and for triple dances, or every third couple is the active couple. The term is applicable to triplet dances, where typically the active couple is the only couple that is active. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, only the active couple—the “1st couple”—initiated the action, other couples supporting their movements and joining in as needed, until they also took their turn as leading couples.

Arm right (or left) – couples link right (or left) arms and move forward in a circle, returning to their starting positions.

Back to back – facing another person, move forward passing right shoulders and fall back to place passing left. May also start by passing left and falling back right. Called a do si do in other dance forms (and dos-à-dos in France).

Balance back – a single backward.

Both hands – two dancers face each other and give hands right to left and left to right.

Cast off – turn outward and dance outside the set.

Cast up (or down) – turn outward and dance up (or down) outside the set.

Changes (starting right or left) – like the circular hey, but dancers give hands as they pass (handing hey). The number of changes is given first (e.g. two changes, three changes, etc.).

Chassé – slipping step to right or left as directed.

Chassé – slipping step to right or left as directed.

Circular hey – dancers face partners or along the line and pass right and left alternating a stated number of changes. Usually done without hands, the circular hey may also be done by more than two couples facing alternately and moving in opposite directions – usually to their original places. This name for the figure was invented by Cecil Sharp and does not appear in sources pre-1900. Nonetheless, some early country dances calling for heys have been interpreted in modern times using circular heys. In early dances, where the hey is called a “double hey”, it works to interpret this as an oval hey, like the modern circular hey but adapted to the straight sides of a longways formation.

Clockwise – in a ring, move to one’s left. In a turn single turn to the right.

Contrary – your contrary is not your partner. In Playford’s original notation, this term meant the same thing that Corner (or sometimes Opposite) means today.

Corner – in a two-couple set, the dancer diagonally opposite, i.e., the first man and the second woman, first woman and second man.

Counter-clockwise – the opposite of clockwise – in a ring, move right. In a turn single, turn to the left.

Cross hands – face and give left to left and right to right.

Cross over – cross with another dancer passing right.

Cross and go below – cross as above and go outside below one couple, ending improper.

Double – four steps forward or back, closing the feet on the 4th step (see “Single” below).

Fall (back) – dance backwards.

Fall (back) – dance backwards.

Figure of 8 – a weaving figure in which dancers pass between two standing people and move around them in a figure 8 pattern. A Full Figure of 8 returns the dancer to original position; a Half Figure of 8 leaves the dancer on the opposite side of the set from original position. In doing this figure, the man lets his partner pass in front of him in some communities; others prefer the rule of “the dancer coming from the left-hand side has right of way”. A double figure of 8 involves four dancers tracing a whole figure of eight around the (now unocccupied) positions of the other couple; half the dancers typically start going around the outside first.

Forward – lead or move in the direction you are facing.

Gypsy – two dancers move around each other in a circular path while facing each other.

Hands across – right or left hands are given to corners, and dancers move in the direction they face.

Hands three, four etc.. – the designated number of dancers form a ring and move around in the direction indicated, usually first to the left and back to the right.

Hey – a weaving figure in which two groups of dancers move in single file and in opposite directions (see circular hey and straight hey).

Honour – couples step forward and right, close, shift weight, and curtsey or bow, then repeat to their left. In the time of Playford’s original manual, a woman’s curtsey was similar to the modern one, but a man’s honour (or reverence) kept the upper body upright and involved sliding the left leg forward while bending the right knee.

Lead – couples join inside hands and walk up or down the set.

“Mad Robin” figure – a back to back with your neighbor while maintaining eye-contact with your partner across the set. Men take one step forward and then slide to the right passing in front of their neighbour, then step backwards and slide left behind their neighbour. Conversely women take one step backwards and then slide to the left passing behind of their neighbour, then step forwards and slide right in front of their neighbour. In some versions, the dancer who is going outside the set at the moment casts out to begin that motion. The term Mad Robin comes from the name of a dance which has the move and was adopted into contra dancing (as a move for all four dancers, unlike the original English dance, where only one couple does it a time) before being readmitted as an all-four figure into English in modern dances.

“Mad Robin” figure – a back to back with your neighbor while maintaining eye-contact with your partner across the set. Men take one step forward and then slide to the right passing in front of their neighbour, then step backwards and slide left behind their neighbour. Conversely women take one step backwards and then slide to the left passing behind of their neighbour, then step forwards and slide right in front of their neighbour. In some versions, the dancer who is going outside the set at the moment casts out to begin that motion. The term Mad Robin comes from the name of a dance which has the move and was adopted into contra dancing (as a move for all four dancers, unlike the original English dance, where only one couple does it a time) before being readmitted as an all-four figure into English in modern dances.

Neighbour – the person you are standing beside, but not your partner.

Opposite – the person you are facing.

Pass – change places with another dancer moving forward and passing by the right shoulder, unless otherwise directed.

Pousette – two dancers face, give both hands and change places as a couple with two adjacent dancers. One pair moves adouble toward one wall, the other toward the other wall. In this half-pousette, couples pass around each other diagonally. To complete the pousette, move in the opposite direction. Dancers end in their original places. In a similar movement, the Draw Pousette, the dancing pairs move on a U-shaped track with one dancer of the pair always moving forwards.

Proper – with the man on the left and the woman on the right, from the perspective of someone facing the music. Improper is the opposite.

Right & left – like the circular hey, but dancers give hands as they pass (handing hey).

Set – a dancer steps right, closes with left foot and shifts weight to it, then steps back to the right foot (right-together-step); then repeats the process mirror-image (left-together-step). In some areas it is done starting to the left. It may be done in place or advancing. Often followed by a turn single.

Siding – two dancers, partners by default if not otherwise specified, go forward in four counts to meet side by side, then back in four counts to where they started the figure. As depicted by Feuillet, this is done right side by right side the first time, left by left the second time.

Single – two steps in any direction closing feet on the second step (the second step tends to be interpreted as a closing action in which weight usually stays on the same foot as before, consistent with descriptions from Renaissance sources).

Slipping circle (left or right) – dancers take hands in a circle (facing in) and chassé left or right.

Hands across or Star – some number of dancers (usually four) join right or left hands in the middle of their circle (facing either CW or CCW). The dancers circle in the direction they face.

Straight hey for four – dancers face alternately, the two in the middle facing out. Dancers pass right shoulders on either end and weave to the end opposite. If the last pass at the end is by the right. the dancer turns right and reenters the line by the same shoulder; vice versa if the last pass was to the left. Dancers end in their original places.

Straight hey for three – the first dancer faces the other two and passes right shoulders with the second dancer, left shoulder with the third – the other dancers moving and passing the indicated shoulder. On making the last pass, each dancer makes a whole turn on the end, bearing right if the last pass was by the right shoulder or left if last pass was by the left, and reenters the figure returning to place. Each dancer describes a figure of eight pattern.

Swing – a turn with two hands, but moving faster and making more than one revolution.

Turn – face, give both hands, and make a complete circular, clockwise turn to place.

Turn by right or left – dancers join right (or left) hands and turn around, separate, and fall to places.

Turn single – dancers turn around in four steps. ‘Turn single right shoulder’ is a clockwise turn; ‘turn single left shoulder’ is a counterclockwise turn.

Up a double and back – common combination in which dancers (usually having linked hands in a line) advance a double and then retire another double.