Ebola Virus Symptoms | Ebola Virus effects on Human Body

Ebola Virus Symptoms | Ebola Virus effects on Human Body

The Ebola virus infection is systemic, meaning that it attacks every organ and tissue of the human body except the bones and skeletal muscles.

Ebola HF is marked by blood clotting and hemorrhaging. Although it is not known exactly how the virus particles attack cells, it is postulated that one factor that allows them to do so is that they release proteins that dampen down the immune system response. The Ebola virus attacks connective tissue multiplying rapidly in collagen. Collagen is the tissue that helps to keep the organs in place. The tissue is basically digested by this virus. The Ebola virus causes small blood clots to form in the bloodstream of the patient; the blood thickens and the blood flow slows down. Blood clots get stuck into blood vessels forming red spots on the patient skin. These grow in size as the disease progress. Also, blood clots does not allow a proper blood supply to many organs such as the liver, brain, lungs, kidneys, intestines, breast tissue, testicles, etc. Spontaneous bleeding then occurs from body orifices and gaps in the skin, such as needle puncture marks and rips that can suddenly appear. Death is caused by huge loss of blood, renal failure, or shock.

A 1976 photograph of two nurses standing in front of Mayinga N’Seka, a person with Ebola virus disease in the 1976 outbreak in Zaire. N’Seka died a few days later due to severe internal hemorrhaging.

A 1976 photograph of two nurses standing in front of Mayinga N’Seka, a person with Ebola virus disease in the 1976 outbreak in Zaire. N’Seka died a few days later due to severe internal hemorrhaging.

Ebola virus disease (EVD), Ebola hemorrhagic fever (EHF) or simply Ebola is a disease of humans and other mammals caused by an ebolavirus. Symptoms start two days to three weeks after contracting the virus, with a fever, sore throat, muscle pain and headaches. Typically, vomiting, diarrhea and rash follow, along with decreased function of the liver and kidneys. Around this time, affected people may begin to bleed both within the body and externally. Death, if it occurs, is typically 6 to 16 days from the start of symptoms and often due to low blood pressure from fluid loss.

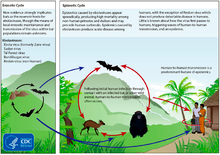

The virus may be acquired upon contact with blood or other bodily fluids of an infected human or other animal. Spreading through the air has not been documented in the natural environment. Fruit bats are believed to be the normal carrier in nature, able to spread the virus without being affected. Humans become infected by contact with the bats or living or dead animals that have been infected by bats. Once human infection occurs, the disease may spread between people as well. Male survivors may be able to transmit the disease via semen for nearly two months. To diagnose EVD, other diseases with similar symptoms such as malaria, cholera and other viral hemorrhagic fevers are first excluded. Blood samples are tested for viral antibodies, viral RNA, or the virus itself to confirm the diagnosis.

Outbreak control requires a coordinated series of medical services, along with a certain level of community engagement. The necessary medical services required include rapid detection and contact tracing, quick access to appropriate laboratory services, proper management of those who are infected, and proper disposal of the dead through cremation or burial. Prevention includes decreasing the spread of disease from infected animals to humans. This may be done by only handling potentially infected bush meat while wearing proper protective clothing and by thoroughly cooking it before consumption. It also includes wearing proper protective clothing and washing hands when around a person with the disease. Samples of bodily fluids and tissues from people with the disease should be handled with special caution.

No specific treatment for the disease is yet available. Efforts to help those who are infected are supportive and include giving either oral rehydration therapy (slightly sweet and salty water to drink) or intravenous fluids. This supportive care improves outcomes. The disease has a high risk of death, killing between 25% and 90% of those infected with the virus (average is 50%). EVD was first identified in an area of Sudan that is now part of South Sudan, as well as in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The disease typically occurs in outbreaks in tropical regions of sub-Saharan Africa. From 1976 (when it was first identified) through 2013, the World Health Organization reported a total of 1,716 cases. The largest outbreak to date is the ongoing 2014 West African Ebola outbreak, which is currently affecting Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia. As of 15 October 2014, 8,998 suspected cases resulting in the deaths of 4,493 have been reported. Efforts are under way to develop a vaccine; however, none yet exists.

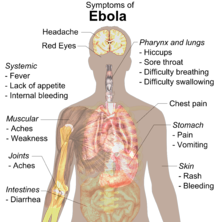

Signs and Symptoms

Signs and symptoms of Ebola virus disease usually begin suddenly with an influenza-like stage characterized by feeling tired, fever, headaches, and pain in the joints, muscles, and abdomen. Vomiting, diarrhea, and loss of appetite are also common. Less common symptoms include sore throat, chest pain, hiccups, shortness of breath, and trouble swallowing. The average time between contracting the infection and the start of symptoms (incubation period) is 8 to 10 days, but it can vary between 2 and 21 days. In about 5-50% of cases, skin manifestations may include a maculopapular rash (a flat, area on the skin that can be red in white skinned people covered with small joined bumps). Early symptoms of EVD may be similar to those of malaria, dengue fever, or other tropical fevers, before the disease progresses to the bleeding phase.

In 40–50% of cases, bleeding from puncture sites and mucous membranes (e.g., gastrointestinal tract, nose, vagina, and gums) has been reported. In the bleeding phase, which typically begins five to seven days after first symptoms, internal and subcutaneous bleeding may present itself in the form of reddened eyes and bloody vomit. Bleeding into the https://valtrexlab.com skin may create petechiae, purpura, ecchymoses, and hematomas (especially around needle injection sites). Sufferers may cough up blood, vomit it, or excrete it in their stool.

Changes on laboratory tests as a result of Ebola virus disease include a low platelet count in the blood, an initially decreased white blood cell count followed by an increase in the white blood cell count, elevated levels of the liver enzymes alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and abnormalities in clotting often consistent with disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) such as a prolonged prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and bleeding time. Heavy bleeding is rare and is usually confined to the gastrointestinal tract. In general, the development of bleeding symptoms often indicates a worse prognosis and this blood loss can result in death. All people infected show some signs of circulatory system involvement, including impaired blood clotting. If the infected person does not recover, death due to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome occurs within 7 to 16 days (usually between days 8 and 9) after first symptoms.

Cause

Main articles: Ebolavirus (taxonomic group) and Ebola virus (specific virus)

Ebola virus disease is caused by four of five viruses classified in the genus Ebolavirus, family Filoviridae, order Mononegavirales. The four disease-causing viruses are Bundibugyo virus (BDBV), Sudan virus (SUDV), Taï Forest virus (TAFV), and one called, simply, Ebola virus (EBOV, formerly Zaire Ebola virus). Ebola virus is the only member of the Zaire ebolavirus species and the most dangerous of the known EVD-causing viruses, as well as being responsible for the largest number of outbreaks. The fifth virus, Reston virus (RESTV), is not thought to be disease-causing in humans. These five viruses are closely related to marburgviruses.

Transmission

Human-to-human transmission occurs only via direct contact with blood or body fluid from an infected person (including embalming of an infected dead body), or by contact with objects contaminated by the virus, particularly needles and syringes. Other body fluids that may transmit ebolaviruses include saliva, mucus, vomit, feces, sweat, tears, breast milk, urine, and semen. Entry points include the nose, mouth, eyes, or open wounds, cuts and abrasions. Transmission from other animals to humans occurs only via contact with, or consumption of, an infected mammal, such as a fruit bat, or ape. The potential for widespread EVD infections in countries with medical systems capable of observing the correct medical isolation procedures where needed is considered low as the disease is only spread by direct contact with the secretions from someone who is showing signs of infection.

A person’s ability to spread the disease is often limited as the individual is often too sick to travel during the infectious stages of the disease. As transmission via air is generally ruled out, the possibility of transmission between non-seat-mate airline passengers is also generally ruled out. Because dead bodies are still infectious, traditional burial rituals may spread the disease. Nearly two thirds of the cases of Ebola infections in Guinea during the 2014 outbreak are believed to have been contracted via unprotected (or unsuitably protected) contact with infected corpses during certain Guinean burial rituals. Semen may be infectious in survivors for up to 7 weeks. It is not entirely clear how an outbreak is initially started. The initial infection is believed to occur after an ebolavirus is transmitted to a human by contact with an infected animal’s body fluids.

One of the primary reasons for spread is that the health systems function poorly in Africa where the disease mostly occurs. Medical workers who do not wear appropriate protective clothing may contract the disease. Hospital-acquired transmission has occurred in the United States and African countries due to the reuse of needles or lack of body substance isolation. Some healthcare centers caring for people with the disease do not have running water.

Airborne transmission has not been documented during EVD outbreaks. They are, however, infectious in rhesus monkeys as breathable 0.8–1.2 μm laboratory-generated droplets.

Reservoir

Bushmeat being prepared for cooking in Ghana, 2013. Human consumption of equatorial animals in Africa in the form of bushmeat has been linked to the transmission of diseases to people, including Ebola.

Bushmeat being prepared for cooking in Ghana, 2013. Human consumption of equatorial animals in Africa in the form of bushmeat has been linked to the transmission of diseases to people, including Ebola.

Bats are considered the most likely natural reservoir of EBOV. Plants, arthropods, and birds were also considered. In the wild, transmission may occur when infected fruit bats drop partially eaten fruits or fruit pulp, then land mammals such as gorillas and duikers may feed on these fallen fruits. This chain of events forms a possible indirect means of transmission from the natural host species to other animal species, which has led to research towards viral shedding in the saliva of fruit bats. Fruit production, animal behavior, and other factors vary at different times and places that may trigger outbreaks among animal populations.

Bats were known to reside in the cotton factory in which the first cases for the 1976 and 1979 outbreaks were observed, and they have also been implicated in Marburg virus infections in 1975 and 1980. Of 24 plant species and 19 vertebrate species experimentally inoculated with EBOV, only bats became infected. The absence of clinical signs in these bats is characteristic of a reservoir species. In a 2002–2003 survey of 1,030 animals including 679 bats from Gabon and the Republic of the Congo, 13 fruit bats were found to contain EBOV RNA fragments. As of 2005, three types of fruit bats (Hypsignathus monstrosus, Epomops franqueti, and Myonycteris torquata) have been identified as being in contact with EBOV. They are now suspected to represent the EBOV reservoir hosts. Antibodies against Zaire and Reston viruses have been found in fruit bats in Bangladesh, thus identifying potential virus hosts and signs of the filoviruses in Asia. Fruit bats are also eaten by people in parts of West Africa where they are smoked, grilled or made into a spicy soup.

Between 1976 and 1998, in 30,000 mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and arthropods sampled from outbreak regions, no Ebola virus was detected apart from some genetic traces found in six rodents (Mus setulosus and Praomys) and one shrew (Sylvisorex ollula) collected from the Central African Republic. Traces of EBOV were detected in the carcasses of gorillas and chimpanzees during outbreaks in 2001 and 2003, which later became the source of human infections. However, the high lethality from infection in these species makes them unlikely as a natural reservoir. Transmission between natural reservoir and humans is rare, and outbreaks are usually traceable to a single case where an individual has handled the carcass of gorilla, chimpanzee or duiker.