East St. Louis Riot

East St. Louis Race Riots

From KETC, Living St. Louis Producer Jim Kirchherr looks back at the ethnic, political and social conflicts taking place in East St. Louis in the early 1900’s. These tensions erupted into violence on July 1, 1917, after police officers were shot.

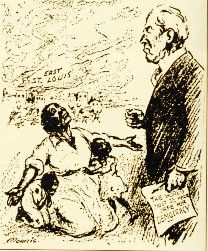

Political cartoon about the East St. Louis massacres of 1917. The caption reads, “Mr. President, why not make America safe for democracy?”, referring to Wilson’s phrase “the world must be made safe for democracy” (portrayed on the document he holds)

Political cartoon about the East St. Louis massacres of 1917. The caption reads, “Mr. President, why not make America safe for democracy?”, referring to Wilson’s phrase “the world must be made safe for democracy” (portrayed on the document he holds)

The East St. Louis Riot (May and July 1917) was an outbreak of labor- and race-related violence that caused between 40 and 200 deaths and extensive property damage. The incident took place in East St. Louis, Illinois, an industrial city on the east bank of the Mississippi River across from St. Louis, Missouri. It has been described as the worst incident of labor-related violence in 20th-century American history, and one of the worst race riots in U.S. history. The local Chamber of Commerce called for the resignation of the police chief. At the end of the month, ten thousand people marched in silent protest in New York City in condemnation of the riots.

Background – East St. Louis riot is located in Illinois East St. Louis Riot

Location of East St. Louis in Illinois.

Location of East St. Louis in Illinois.

In 1917 the United States had an active economy boosted by World War I. With many would-be workers absent for active service in the war, industries were in need of labor. Seeking better work and living opportunities, as well as an escape from harsh conditions, the Great Migration out of the South toward industrial centers across the northern and midwestern United States was well underway. For example, blacks were arriving in St. Louis during Spring 1917 at the rate of 2,000 per week. When industries became embroiled in labor strikes, traditionally white unions sought to strengthen their bargaining position by hindering or excluding black workers, while industry owners utilizing blacks as replacements or strikebreakers added to the deep existing societal divisions.

While in New Orleans on a lecture tour, Marcus Garvey became aware that Louisiana farmers and the Board of Trade were worried about losing their labor force, and had requested East St. Louis Mayor Mollman’s assistance during his New Orleans visit that same week to help discourage black migration.

With many African Americans finding work at the Aluminum Ore Company and the American Steel Company in East St. Louis, some whites feared job and wage security due to this new competition; they further resented newcomers arriving from a rural and very different culture. Tensions between the groups escalated, including rumors of black men and white women fraternizing at a labor meeting on May 28.

Riot

In May, three thousand white men gathered in downtown East St. Louis and attacks on blacks began. With mobs destroying buildings and beating people, the Illinois governor called in the National Guard to prevent further rioting. Although rumors circulated about organized retribution attacks from African Americans, conditions eased somewhat for a few weeks.

In May, three thousand white men gathered in downtown East St. Louis and attacks on blacks began. With mobs destroying buildings and beating people, the Illinois governor called in the National Guard to prevent further rioting. Although rumors circulated about organized retribution attacks from African Americans, conditions eased somewhat for a few weeks.

On July 2, a car occupied by white males drove through a black area of the city and fired several shots into a standing group. An hour later, a car containing four people, including a journalist and two police officers (Detective Sergeant Samuel Coppedge and Detective Frank Wadley) was passing through the same area. Black residents, possibly assuming they were the original suspects, opened fire on their car, killing one officer instantly and mortally wounding another. Later that day, thousands of white spectators who assembled to view the detectives’ bloodstained automobile marched into the black section of town and started rioting. After cutting the water hoses of the fire department, the rioters burned entire sections of the city and shot inhabitants as they escaped the flames. Claiming that “Southern negros deserved a genuine lynching,” they lynched several blacks. Guardsmen were called in but accounts exist that they joined in the rioting rather than stopping it. More joined in, including allegedly “ten or fifteen young girls about 18 years old, who chased a negro woman at the Relay Depot at about 5 o’clock. The girls were brandishing clubs and calling upon the men to kill the woman.”

Aftermath – Death Toll

After the riot, varying estimates of the death toll circulated. The police chief estimated that 100 blacks had been killed. The renowned journalist Ida B. Wells reported in The Chicago Defender that 40-150 black people were killed during July in the rioting in East St. Louis. The N.A.A.C.P. estimated deaths at 100-200. Six thousand blacks were left homeless after their neighborhood was burned. A Congressional Investigating Committee concluded that no precise death toll could be determined, but reported that at least 8 whites and 39 blacks died. While the coroner specified 9 white deaths, the deaths of black victims were less clearly recorded. Activists who disputed the Committee’s conclusion, argued that the true number of deaths would never be known because many corpses were not recovered, or did not pass through the hands of undertakers.

After the riot, varying estimates of the death toll circulated. The police chief estimated that 100 blacks had been killed. The renowned journalist Ida B. Wells reported in The Chicago Defender that 40-150 black people were killed during July in the rioting in East St. Louis. The N.A.A.C.P. estimated deaths at 100-200. Six thousand blacks were left homeless after their neighborhood was burned. A Congressional Investigating Committee concluded that no precise death toll could be determined, but reported that at least 8 whites and 39 blacks died. While the coroner specified 9 white deaths, the deaths of black victims were less clearly recorded. Activists who disputed the Committee’s conclusion, argued that the true number of deaths would never be known because many corpses were not recovered, or did not pass through the hands of undertakers.

Response of Black Community

The ferocious brutality of the attacks and the failure of the authorities to protect innocent lives contributed to the radicalization of many blacks in St. Louis and the nation. Marcus Garvey declared in an inflammatory speech that the riot was “one of the bloodiest outrages against mankind” and a “wholesale massacre of our people”, insisting that “This is no time for fine words, but a time to lift one’s voice against the savagery of a people who claim to be the dispensers of democracy.”

The ferocious brutality of the attacks and the failure of the authorities to protect innocent lives contributed to the radicalization of many blacks in St. Louis and the nation. Marcus Garvey declared in an inflammatory speech that the riot was “one of the bloodiest outrages against mankind” and a “wholesale massacre of our people”, insisting that “This is no time for fine words, but a time to lift one’s voice against the savagery of a people who claim to be the dispensers of democracy.”

In New York City on July 28, ten thousand black people marched down Fifth Avenue in a Silent Parade, protesting the East St. Louis riots. They carried signs that highlighted protests about the riots. The march was organized by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), W. E. B. Du Bois, and groups in Harlem. Women and children were dressed in white; the men were dressed in black.

Response of Business Community

On July 6 representatives of the Chamber of Commerce met with the mayor to demand the resignation of the Police Chief and Night Police Chief, or radical reform. They were outraged about the rioting and accused the mayor of having allowed a “reign of lawlessness.” In addition to the riots taking the lives of too many innocent people, mobs had caused extensive property damage. The Southern Railway Company’s warehouse was burned, with over 100 car loads of merchandise, at a loss to the company of over $525,000; a white theatre valued at over $100,000 was also destroyed.