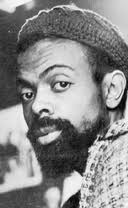

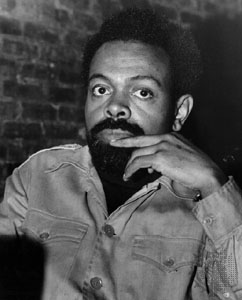

Amiri Baraka

Amiri Baraka (born 1934 – died Jan. 9, 2014): Poet-Playwright-Activist Who Shaped Revolutionary Politics, Black Culture

We’ll spend the hour looking at the life and legacy of Amiri Baraka, the poet, playwright and political organizer who died Thursday at the age of 79. Baraka was a leading force in the Black Arts Movement of the 1960’s and 1970’s. In 1963 he published “Blues People: Negro Music in White America,” known as the first major history of black music to be written by an African American. A year later he published a collection of poetry titled “The Dead Lecturer” and won an Obie Award for his play, “Dutchman.” After the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965, he moved to Harlem and founded the Black Arts Repertory Theatre. In the late 1960’s, Baraka moved back to his hometown of Newark and began focusing more on political organizing, prompting the FBI to identify him as “the person who will probably emerge as the leader of the pan-African movement in the United States.” Baraka continued writing and performing poetry up until his hospitalization late last year, leaving behind a body of work that greatly influenced a younger generation of hip-hop artists and slam poets. We are joined by four of Baraka’s longtime comrades and friends: Sonia Sanchez, a renowned writer, poet, playwright and activist; Felipe Luciano, a poet, activist, journalist and writer who was an original member of the poetry and musical group The Last Poets; Komozi Woodard, a professor of history at Sarah Lawrence College and author of “A Nation Within a Nation: Amiri Baraka and Black Power Politics”; and Larry Hamm, chairman of the People’s Organization for Progress in Newark, New Jersey.

We’ll spend the hour looking at the life and legacy of Amiri Baraka, the poet, playwright and political organizer who died Thursday at the age of 79. Baraka was a leading force in the Black Arts Movement of the 1960’s and 1970’s. In 1963 he published “Blues People: Negro Music in White America,” known as the first major history of black music to be written by an African American. A year later he published a collection of poetry titled “The Dead Lecturer” and won an Obie Award for his play, “Dutchman.” After the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965, he moved to Harlem and founded the Black Arts Repertory Theatre. In the late 1960’s, Baraka moved back to his hometown of Newark and began focusing more on political organizing, prompting the FBI to identify him as “the person who will probably emerge as the leader of the pan-African movement in the United States.” Baraka continued writing and performing poetry up until his hospitalization late last year, leaving behind a body of work that greatly influenced a younger generation of hip-hop artists and slam poets. We are joined by four of Baraka’s longtime comrades and friends: Sonia Sanchez, a renowned writer, poet, playwright and activist; Felipe Luciano, a poet, activist, journalist and writer who was an original member of the poetry and musical group The Last Poets; Komozi Woodard, a professor of history at Sarah Lawrence College and author of “A Nation Within a Nation: Amiri Baraka and Black Power Politics”; and Larry Hamm, chairman of the People’s Organization for Progress in Newark, New Jersey.

TRANSCRIPT: This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: We will spend the rest of the hour remembering the life and legacy of the poet, playwright and political organizer Amiri Baraka. He died on Thursday in Newark, New Jersey, at the age of 79. Baraka was a leading force in the Black Arts Movement of the 1960’s and 1970’s, but he first came to prominence as a Beat Generation poet when he co-founded the journal Yugen and published the works of Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and Gregory Corso.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: We will spend the rest of the hour remembering the life and legacy of the poet, playwright and political organizer Amiri Baraka. He died on Thursday in Newark, New Jersey, at the age of 79. Baraka was a leading force in the Black Arts Movement of the 1960’s and 1970’s, but he first came to prominence as a Beat Generation poet when he co-founded the journal Yugen and published the works of Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and Gregory Corso.

At the time, he was known as LeRoi Jones. In 1963, he publishedBlues People: Negro Music in White America. The book has been called the first major history of black music to be written by an African American. A year later he published a collection of poetry titled The Dead Lecturer and won an Obie Award for his play,Dutchman.

AMY GOODMAN: Dutchman was the last play he published under his birth name, LeRoi Jones. After the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965, he moved to Harlem and founded the Black Arts Repertory Theatre. He soon became a leader of what was known as the Black Arts Movement. In 2007, he appeared on Democracy Now! and talked about his name change.

AMIRI BARAKA: “I was Everett LeRoi Jones. My grandfather’s name was Everett. He was a politician in that town. My family came to Newark in the ’20s. We’ve been there a long, long time. My father’s name was LeRoi, the French-ified aspect of it, because his first name was Coyette, you see. They come from South Carolina. I changed my name when we became aware of the African revolution and the whole question of our African roots. I was named by the man who buried Malcolm X, Hesham Jabbar, who died last week. He named me Amir Barakat. But that’s Arabic. I brought it down into Swahililand, into Tanzania, which is an accent. So it’s Amiri, instead of Amir, and, you know, Baraka, rather than Barakat, you know, which is interesting. If it was Amir Barakat, I would probably have more difficulty flying these days.”

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: In the late 1960’s, Amiri Baraka moved back to his home town of Newark and began focusing more on political organizing. In 1967, he was nearly beaten to death by police during the urban uprising in Newark. The FBI once identified Baraka as, quote, “the person who will probably emerge as the leader of the pan-African movement in the United States.” Three years later, in 1970, he formed the Congress of African People and spoke at the Black Political Convention in Gary, Indiana, two years later.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: In the late 1960’s, Amiri Baraka moved back to his home town of Newark and began focusing more on political organizing. In 1967, he was nearly beaten to death by police during the urban uprising in Newark. The FBI once identified Baraka as, quote, “the person who will probably emerge as the leader of the pan-African movement in the United States.” Three years later, in 1970, he formed the Congress of African People and spoke at the Black Political Convention in Gary, Indiana, two years later.

Amiri Baraka continued writing and performing poetry up until he was hospitalized late last year. In 2002, he was named poet laureate of New Jersey, a post that was eliminated after a poem he wrote about the September 11th attacks turned out to create a firestorm throughout the country and the state.

AMY GOODMAN: Amiri Baraka’s work also greatly influenced a younger generation of hip-hop artists and slam poets. In a moment, we’ll be joined by four guests to talk more about Amiri’s life and legacy, but first let’s turn to a performance of his on the program Def Poetry Jam on HBO.

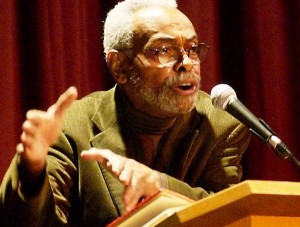

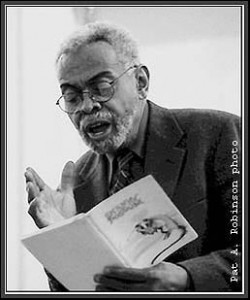

Baraka at the Miami Book Fair International

Baraka at the Miami Book Fair International

Amiri Baraka (born Everett LeRoi Jones; October 7, 1934 – January 9, 2014), formerly known as LeRoi Jones and Imamu Amear Baraka, was an American writer of poetry,drama, fiction, essays and music criticism. He was the author of numerous books of poetry and taught at a number of universities, including the State University of New York at Buffalo and the State University of New York at Stony Brook. He received the PEN Open Book Award, formerly known as the Beyond Margins Award, in 2008 for Tales of the Out and the Gone.

Baraka’s poetry and writing has attracted both extreme praise and condemnation. Within the African-American community, some compare him to James Baldwin and call Baraka one of the most respected and most widely published Black writers of his generation. Others have said his work is an expression of violence, misogyny, homophobia and racism. Baraka’s brief tenure as Poet Laureate of New Jersey (2002–03), involved controversy over a public reading of his poem “Somebody Blew Up America?” and accusations of anti-semitism, and some negative attention from critics, and politicians.

Biography – Early life (1934–65)

Biography – Early life (1934–65)

Baraka was born Everett LeRoi Jones in Newark, New Jersey, where he attended Barringer High School. His father, Coyt Leverette Jones, worked as a postal supervisor and lift operator. His mother, Anna Lois (née Russ), was a social worker. In 1967, he adopted the Muslim name Imamu Amear Baraka, which he later changed to Amiri Baraka.

He won a scholarship to Rutgers University in 1951, but a continuing sense of cultural dislocation prompted him to transfer in 1952 to Howard University, which he left without obtaining a degree. His major fields of study were philosophy and religion. Baraka subsequently studied at Columbia University and the New School for Social Research without obtaining a degree.

In 1954, he joined the US Air Force as a gunner, reaching the rank of sergeant. However, his commanding officer received an anonymous letter accusing Baraka of being a communist, which led to the discovery of Soviet writings, his reassignment to gardening duty and subsequently a dishonorable discharge for violation of his oath of duty.

The same year, he moved to Greenwich Village working initially in a warehouse for music records. His interest in jazz began during this period. At the same time he came into contact with avant-garde Beat Generation, Black Mountain poets and New York School poets. In 1958 he married Hettie Cohen, with whom he had two daughters, Kellie Jones (b. 1959) and Lisa Jones (b.1961). He and Hettie founded Totem Press, which published such Beat icons as Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg. They also jointly founded a quarterly literary magazine Yugen, which ran for eight issues (1958–62). Baraka also worked as editor and critic for the literary and arts journal Kulchur (1960–65). With Diane di Prima he edited the first twenty-five issues (1961–63) of their little magazine The Floating Bear. In the autumn of 1961 he co-founded the New York Poets Theatre with di Prima, choreographers Fred Herko andJames Waring, and actor Alan S. Marlowe. He had an extramarital affair with Diane di Prima for several years; their daughter, Dominique di Prima, was born in June 1962.

Baraka visited Cuba in July 1960 with a Fair Play for Cuba Committee delegation and reported his impressions in his essay “Cuba libre.” In 1961 Baraka co-authored a Declaration of Conscience in support of Fidel Castro‘s regime. Baraka also was a member of the Umbra Poets Workshop of emerging Black Nationalist writers (Ishmael Reed, and Lorenzo Thomas among others) on the Lower East Side (1962–65). In 1961 a first book of poems, Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note, was published. Baraka’s article “The Myth of a ‘Negro Literature'” (1962) stated that “a Negro literature, to be a legitimate product of the Negro experience in America, must get at that experience in exactly the terms America has proposed for it in its most ruthless identity.” He also states in the same work that as an element of American culture, the Negro was entirely misunderstood by Americans. The reason for this misunderstanding and for the lack of black literature of merit was according to Jones:

Baraka visited Cuba in July 1960 with a Fair Play for Cuba Committee delegation and reported his impressions in his essay “Cuba libre.” In 1961 Baraka co-authored a Declaration of Conscience in support of Fidel Castro‘s regime. Baraka also was a member of the Umbra Poets Workshop of emerging Black Nationalist writers (Ishmael Reed, and Lorenzo Thomas among others) on the Lower East Side (1962–65). In 1961 a first book of poems, Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note, was published. Baraka’s article “The Myth of a ‘Negro Literature'” (1962) stated that “a Negro literature, to be a legitimate product of the Negro experience in America, must get at that experience in exactly the terms America has proposed for it in its most ruthless identity.” He also states in the same work that as an element of American culture, the Negro was entirely misunderstood by Americans. The reason for this misunderstanding and for the lack of black literature of merit was according to Jones:

“In most cases the Negroes who found themselves in a position to pursue some art, especially the art of literature, have been members of the Negro middle class, a group that has always gone out of its way to cultivate any mediocrity, as long as that mediocrity was guaranteed to prove to America, and recently to the world at large, that they were not really who they were, i.e., Negroes.”

As long as the black writer was obsessed with being an accepted, middle class, Baraka wrote, he would never be able to speak his mind, and that would always lead to failure. Baraka felt that America only made room for only white obfuscators, not black ones.

In 1963 Baraka (under the name Jones) published Blues People: Negro Music in White America, his account of the significance of blues and jazz in African-American culture. When the work was re-issued in 1999, Baraka wrote in the Introduction that he wished to show: “The music was the score, the actually expressed creative orchestration, reflection of Afro-American life…. That the music was explaining the history as the history was explaining the music. And that both were expressions of and reflections of the people.” Baraka argued that though the slaves had brought their musical traditions from Africa, the blues were an expression of what black people became in America: “The way I have come to think about it, blues could not exist if the African captives had not become American captives.”

Baraka (under the name Jones) authored an acclaimed, controversial play Dutchman, in which a white woman accosts a black man on the New York subway. The play premiered in 1964 and received the Obie Award for Best American Play in the same year. A film of the play, directed by Anthony Harvey, was released in 1967. The play has been revived several times, including a 2013 production staged in the Russian and Turkish Bathhouse in the East Village, New York.

After the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965, Baraka left his wife and their two children and moved to Harlem. Now a “black cultural nationalist,” he broke away from the predominantly white Beats and became very critical of the pacifist and integrationist Civil Rights movement. His revolutionary poetry now became more controversial. A poem such as “Black Art” (1965), according to academic Werner Sollors from Harvard University, expressed his need to commit the violence required to “establish a Black World.” “Black Art” quickly became the major poetic manifesto of the Black Arts Literary Movement and in it, Jones declaimed “we want poems that kill,” which coincided with the rise of armed self-defense and slogans such as “Arm yourself or harm yourself” that promoted confrontation with the white power structure. Rather than use poetry as an escapist mechanism, Baraka saw poetry as a weapon of action. His poetry demanded violence against those he felt were responsible for an unjust society.

After the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965, Baraka left his wife and their two children and moved to Harlem. Now a “black cultural nationalist,” he broke away from the predominantly white Beats and became very critical of the pacifist and integrationist Civil Rights movement. His revolutionary poetry now became more controversial. A poem such as “Black Art” (1965), according to academic Werner Sollors from Harvard University, expressed his need to commit the violence required to “establish a Black World.” “Black Art” quickly became the major poetic manifesto of the Black Arts Literary Movement and in it, Jones declaimed “we want poems that kill,” which coincided with the rise of armed self-defense and slogans such as “Arm yourself or harm yourself” that promoted confrontation with the white power structure. Rather than use poetry as an escapist mechanism, Baraka saw poetry as a weapon of action. His poetry demanded violence against those he felt were responsible for an unjust society.

1966–80

In 1966, Baraka married his second wife, Sylvia Robinson, who later adopted the name Amina Baraka. In 1967, he lectured at San Francisco State University. The year after, he was arrested in Newark for having allegedly carried an illegal weapon and resisting arrest during the 1967 Newark riots, and was subsequently sentenced to three years in prison. Shortly afterward an appeals court reversed the sentence based on his defense by attorney, Raymond A. Brown. Not long after the 1967 riots, Baraka generated controversy when he went on the radio with a Newark police captain and Anthony Imperiale, a Politician and private business owner, and the three of them blamed the riots on “white-led, so-called radical groups” and “Communists and the Trotskyite persons.” That same year his second book of jazz criticism, Black Music, came out, a collection of previously published music journalism, including the seminal Apple Cores columns from Down Beat magazine.

In 1967, Baraka (still Leroi Jones) visited Maulana Karenga in Los Angeles and became an advocate of his philosophy of Kawaida, a multifaceted, categorized activist philosophy that produced the “Nguzo Saba,” Kwanzaa, and an emphasis on African names. It was at this time that he adopted the name Imamu Amear Baraka. Imamu is a Swahili title for “spiritual leader”, derived from the Arabic word Imam (إمام). According to Shaw, he dropped the honorific Imamu and eventually changed Amear (which means “Prince”) to Amiri. Baraka means “blessing, in the sense of divine favor.” In 1970 he strongly supported Kenneth A. Gibson‘s candidacy for mayor of Newark; Gibson was elected the city’s first Afro-American Mayor. In the late 1960’s and early 1970s, Baraka courted controversy by penning some strongly anti-Jewish poems and articles, similar to the stance at that time of the Nation of Islam.

In 1967, Baraka (still Leroi Jones) visited Maulana Karenga in Los Angeles and became an advocate of his philosophy of Kawaida, a multifaceted, categorized activist philosophy that produced the “Nguzo Saba,” Kwanzaa, and an emphasis on African names. It was at this time that he adopted the name Imamu Amear Baraka. Imamu is a Swahili title for “spiritual leader”, derived from the Arabic word Imam (إمام). According to Shaw, he dropped the honorific Imamu and eventually changed Amear (which means “Prince”) to Amiri. Baraka means “blessing, in the sense of divine favor.” In 1970 he strongly supported Kenneth A. Gibson‘s candidacy for mayor of Newark; Gibson was elected the city’s first Afro-American Mayor. In the late 1960’s and early 1970s, Baraka courted controversy by penning some strongly anti-Jewish poems and articles, similar to the stance at that time of the Nation of Islam.

Baraka’s separation from the Black Arts Movement began because he saw certain black writers – capitulationists, as he called them – countering the Black Arts Movement that he created. He believed that the groundbreakers in the Black Arts Movement were doing something that was new, needed, useful, and black, and those who did not want to see a promotion of black expression were “appointed” to the scene to damage the movement. Around 1974, Baraka distanced himself from Black nationalism and became a Marxist and a supporter of third-world liberation movements. In 1979 he became a lecturer in Stony Brook University‘s Africana Studies Department. The same year, after altercations with his wife, he was sentenced to a short period of compulsory community service. Around this time he began writing his autobiography. In 1980 he denounced his former anti-semitic utterances, declaring himself an anti-zionist.

1980–2014

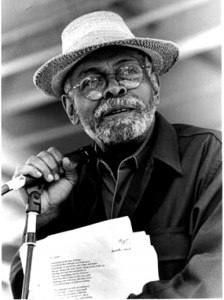

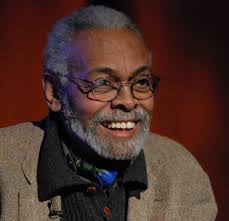

Baraka addressing the Malcolm X Festival from the Black Dot Stage in San Antonio Park, Oakland, California while performing with Marcel Diallo and his Electric Church Band

Baraka addressing the Malcolm X Festival from the Black Dot Stage in San Antonio Park, Oakland, California while performing with Marcel Diallo and his Electric Church Band

During the 1982–83 academic year, Baraka was a visiting professor at Columbia University, where he taught a course entitled “Black Women and Their Fictions.” In 1984 he became a full professor at Rutgers University, but was subsequently denied tenure. In 1985, Baraka returned to Stony Brook, eventually becoming professor emeritus of African Studies. In 1987, together with Maya Angelou and Toni Morrison, he was a speaker at the commemoration ceremony for James Baldwin. In 1989 Baraka won an American Book Award for his works as well as a Langston Hughes Award. In 1990 he co-authored the autobiography of Quincy Jones, and 1998 was a supporting actor in Warren Beatty‘s film Bulworth. In 1996, Baraka contributed to the AIDS benefit album Offbeat: A Red Hot Soundtrip produced by the Red Hot Organization.

In July 2002, Baraka was named Poet Laureate of New Jersey by Governor Jim McGreevey. Baraka held the post for a year mired in controversy and after substantial political pressure and public outrage demanding his resignation. During the Geraldine R. Dodge Poetry Festival in Stanhope, New Jersey, Baraka read his 2001 poem on the September 11th attacks“Somebody Blew Up America?”, which was criticized for anti-Semitism and attacks on public figures. Because there was no mechanism in the law to remove Baraka from the post, the position of state poet laureate was officially abolished by the State Legislature and Governor McGreevey.

Baraka collaborated with hip-hop group The Roots on the song “Something in the Way of Things (In Town)” on their 2002 album Phrenology.

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante included Amiri Baraka on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante included Amiri Baraka on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

In 2003, Baraka’s daughter Shani, aged 31, and her lesbian partner, Rayshon Homes, were murdered in the home of Shani’s sister, Wanda Wilson Pasha, by Pasha’s ex-husband, James Coleman. Prosecutors argued that Coleman shot Shani because she had helped her sister separate from her husband. A New Jersey jury found Coleman (also known as Ibn El-Amin Pasha) guilty of murdering Shani Baraka and Rayshon Holmes, and he was sentenced to 168 years in prison for the 2003 shooting.

Death

Amiri Baraka died on January 9, 2014, at Beth Israel Medical Center in Newark, New Jersey, after being hospitalized in the facility’s intensive care unit for one month prior to his death. The cause of death was not reported, but it is mentioned that Baraka had a long struggle with diabetes.

http://www.democracynow.org/2014/1/10/amiri_baraka_1934_2014_poet_playwright