#15. St. Paul’s Cathedral

St Paul’s Cathedral in London – 1942 Social Guidance / Educational Documentary

A stately exploration of the history of St Paul’s Cathedral in London, with a focus on the architecture and individuals buried there, and the impact of the Blitz. A picture of St. Paul’s Cathedral, past and present. Old St. Paul’s; St. Paul’s rebuilt by Wren; St. Paul’s the shrine of an Empire’s heroes—- Nelson, Wellington, Roberts, Kitchener, Jellicoe, Beatty. The film shows recent historic occasions, and the great Dome riding high above the blitz of 1940. It ends with a thanksgiving service on the steps of the bomb-scarred Cathedral.’ (Films of Britain – British Council Film Department Catalogue – 1942-43). This film has been made available for non-commercial research and educational purposes courtesy the British Council Film Collection. http://film.britishcouncil.org/britis…

St. Paul’s Cathedral Location: London, UK Architect: Christopher Wren Year: 1710

St. Paul’s Cathedral Location: London, UK Architect: Christopher Wren Year: 1710

Wren was responsible for designing 51 churches after the great fire of 1651 torched London. The most famous is St. Paul’s, which has one of the tallest domes in the world and was London’s single tallest building until 1962.

Cathedral Church of St Paul the Apostle St Paul’s Cathedral

Cathedral Church of St Paul the Apostle St Paul’s Cathedral

London, is a Church of England cathedral, the seat of the Bishop of London and mother church of the Diocese of London. It sits at the top of Ludgate Hill, the highest point in the City of London. Its dedication to Paul the Apostle dates back to the original church on this site, founded in AD 604. The present church, dating from the late 17th century, was designed in the English Baroque style by Sir Christopher Wren. Its construction, completed within Wren’s lifetime, was part of a major rebuilding programme which took place in the city after the Great Fire of London. The cathedral is one of the most famous and most recognisable sights of London, with its dome, framed by the spires of Wren’s City churches, dominating the skyline for 300 years. At 365 feet (111 m) high, it was the tallest building in London from 1710 to 1962, and its dome is also among the highest in the world. In terms of area, St Paul’s is the second largest church building in the United Kingdom after Liverpool Cathedral. St Paul’s Cathedral occupies a significant place in the national identity of the English population. It is the central subject of much promotional material, as well as postcard images of the dome standing tall, surrounded by the smoke and fire of the Blitz. Important services held at St Paul’s include the funerals of Lord Nelson, the Duke of Wellington, Sir Winston Churchill and Margaret Thatcher; Jubilee celebrations for Queen Victoria; peace services marking the end of the First and Second World Wars; the wedding of Charles, Prince of Wales, and Lady Diana Spencer, the launch of the Festival of Britain and the thanksgiving services for the Golden Jubilee, the 80th Birthday and the Diamond Jubilee of Elizabeth II. St Paul’s Cathedral is a busy working church, with hourly prayer and daily services.

History: Pre-Norman cathedrals

There was a late-Roman episcopal see in London, and Bishop Restitutus of London attended the Council of Arles in AD 314. The location of Roman London’s cathedral is unknown, although it has been argued that a large and ornate 4th-century building on Tower Hill, remains of which were excavated in 1989, may have been the cathedral. The Elizabethan antiquarian William Camden argued that a Roman temple dedicated to the goddess Diana had once stood on the site of the medieval St Paul’s cathedral. Christopher Wren reported that he had found no trace of any such temple during the works to build the new cathedral after the Great Fire, and Camden’s hypothesis is not accepted by modern archaeologists. Bede records that in AD 604 St Augustine consecrated Mellitus as the first bishop to the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Saxons and their king, Sæberht. Sæberht’s uncle and overlord, Æthelberht, king of Kent, built a church dedicated to St Paul in London, as the seat of the new bishop. It is assumed, although unproven, that this first Anglo-Saxon cathedral stood on the same site as the later medieval and the present cathedrals. On the death of Sæberht in about 616, his pagan sons expelled Mellitus from London, and the East Saxons reverted to paganism. The fate of the first cathedral building is unknown. Christianity was restored among the East Saxons in the late 7th-century and it is presumed that either the Anglo-Saxon cathedral was restored or a new building erected as the seat of bishops such as Cedd, Wine and Earconwald, the last of whom was buried in the cathedral in 693. This building, or a successor, was destroyed by fire in 962, but rebuilt in the same year. King Æthelred the Unready was buried in the cathedral on his death in 1016. The cathedral was burnt, with much of the city, in a fire in 1087, as recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

Old St Paul’s Cathedral

The fourth St Paul’s, generally referred to as Old St Paul’s, was begun by the Normans after the 1087 fire. A further fire in 1136 disrupted the work, and the new cathedral was not consecrated until 1240. During the period of construction, the style of architecture had changed from Romanesque to Gothic and this was reflected in the pointed arches and larger windows of the upper parts and East End of the building. The Gothic ribbed vault was constructed, like that of York Minster, of wood rather than stone, which affected the ultimate fate of the building.

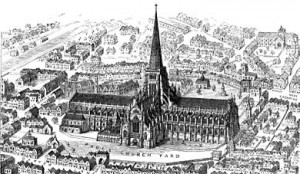

Old St Paul’s prior to 1561, with intact spire

An enlargement program commenced in 1256. This ‘New Work’ was consecrated in 1300 but not complete until 1314. During the later Medieval period St Paul’s was exceeded in length only by the Abbey Church of Cluny and in the height of its spire only by Lincoln Cathedral and St. Mary’s Church, Stralsund. Excavations by Francis Penrose in 1878 showed that it was 585 feet (178 m) long and 100 feet (30 m) wide (290 feet or 87 m across the transepts and crossing). The spire was about 489 feet (149 m). By the 16th century the building was starting to decay. Under Henry VIII and Edward VI, the Dissolution of the Monasteriesand Chantries Acts led to the destruction of interior ornamentation and the cloisters, charnels, crypts, chapels,shrines, chantries and other buildings in St Paul’s Churchyard. Many of these former religious sites in the churchyard, having been seized by the Crown, were sold as shops and rental properties, especially to printers and booksellers, who were often Puritans. In 1561 the spire was destroyed by lightning, an event that was taken by both Protestants and Roman Catholics as a sign of God‘s displeasure at the other faction. In the 1630s a west front was added to the building by England’s first classical architect, Inigo Jones. There was much defacing and mistreatment of the building by Parliamentarian forces during the Civil War, and the old documents and charters were dispersed and destroyed. During the Commonwealth, those churchyard buildings that were razed supplied ready-dressed building material for construction projects, such as the Lord Protector’s city palace, Somerset House. Crowds were drawn to the northeast corner of the churchyard, St Paul’s Cross, where open-air preaching took place. In the Great Fire of London of 1666, Old St Pauls was gutted. While it might have been possible to reconstruct it, a decision was taken to build a new cathedral in a modern style. This course of action had been proposed even before the fire.

Present St Paul’s  An aerial view of St Paul’s

An aerial view of St Paul’s

The task of designing a replacement structure was officially assigned to Sir Christopher Wren on 30 July 1669. He had previously been put in charge of the rebuilding of churches to replace those lost in the Great Fire. More than fifty City churches are attributable to Wren. Concurrent with designing St Paul’s, Wren was enagaged in the production of his five Tractson Architecture. Wren had begun advising on the repair of the Old St Paul’s in 1661, five years before the Great Fire of London in 1666. The proposed work included renovations to both interior and exterior that would complement the Classical facade designed by Inigo Jones in 1630. Wren planned to replace the dilapidated tower with a dome, using the existent structure as a scaffold. He produced a drawing of the proposed dome, showing that it was at this stage at which he conceived the idea that it should span both nave and aisles at the crossing. After the fire, It was at first thought possible to retain a substantial part of the old cathedral, but ultimately the entire structure was demolished in the early 1670’s to start afresh. In July 1668 Dean William Sancroft wrote to Christopher Wren that he was charged by the Archbishop of Canterbury, in agreement with the Bishops of London and Oxford to design a new cathedral that was “handsome and noble to all the ends of it and to the reputation of the City and the nation.” The design process took several years, but a design was finally settled and attached to a royal warrant, with the proviso that Wren was permitted to make any further changes that he deemed necessary. The result was the present St Paul’s Cathedral, still the second largest church in Britain and with a dome proclaimed as the finest in the world. The building was financed by a tax on coal, and was completed within its architect’s lifetime, and with many of the major contractors employed for the duration. The “topping out” of the cathedral (when the final stone was placed on the lantern) took place on 26 October 1708, performed by Wren’s son Christopher Jr and the son of one of the masons. The cathedral was declared officially complete by Parliament on 25 December 1711 (Christmas Day). In fact, construction was to continue for several years after that, with the statues on the roof only being added in the 1720s. In 1716 the total costs amounted to £1,095,556 (£139 million in 2013).

Consecration

On 2 December 1697, only thirty-two years and three months after the Great Fire destroyed Old St Paul’s, the new cathedral was consecrated for use. The Right Reverend Henry Compton, Bishop of London, preached the sermon. It was based on the text of Psalm 122, “I was glad when they said unto me: Let us go into the house of the Lord.” The first regular service was held on the following Sunday. Opinions of Wren’s cathedral differed, with some loving it: Without, within, below, above, the eye / Is filled with unrestrained delight, while others hated it: …There was an air of Popery about the gilded capitals, the heavy arches…They were unfamiliar, un-English...

St. Paul’s, seen across the River Thames, 1850

Since 1900 – War damage

The iconic St Paul’s Survives taken on 29 December 1940 of St Paul’s during The Blitz

The iconic St Paul’s Survives taken on 29 December 1940 of St Paul’s during The Blitz

The cathedral survived despite being targeted during the Blitz — it was struck by bombs on 10 October 1940 and 17 April 1941. On 12 September 1940 a time-delayed bomb that had struck the cathedral was successfully defused and removed by a bomb disposal detachment of Royal Engineers under the command of Temporary Lieutenant Robert Davies. Had this bomb detonated, it would have totally destroyed the cathedral, as it left a 100-foot (30 m) crater when later remotely detonated in a secure location. As a result of this action, Davies and Sapper George Cameron Wylie were both awarded the George Cross. Davies’ George Cross and other medals are on display at the Imperial War Museum, London. One of the best known images of London during the war was a photograph of St Paul’s taken on the 29 December 1940 during the “Second Great Fire of London” by photographer Herbert Mason, from the roof of the Daily Mail in Tudor Street showing the cathedral shrouded in smoke. Lisa Jardine of Queen Mary, University of London, has written:

“Wreathed in billowing smoke, amidst the chaos and destruction of war, the pale dome stands proud and glorious – indomitable. At the height of that air-raid, Sir Winston Churchill telephoned the Guildhall to insist that all fire-fighting resources be directed at St Paul’s. The cathedral must be saved, he said, damage to the fabric would sap the morale of the country.”

Restoration  Extensive copper, lead and slate renovation work on the Dome in 1996 by John B. Chambers. A 15-year restoration project – one of the largest ever undertaken in the UK – was completed on 15 June 2011.

Extensive copper, lead and slate renovation work on the Dome in 1996 by John B. Chambers. A 15-year restoration project – one of the largest ever undertaken in the UK – was completed on 15 June 2011.

Occupy London

In October 2011 an anti-capitalism Occupy London encampment was established in front of the cathedral. The cathedral’s finances came under scrutiny. It was claimed that the cathedral was losing revenue of £20,000 per day. Canon Chancellor Giles Fraser resigned, warning that to evict the anti-capitalist activists would constitute “violence in the name of the Church.” The encampment was evicted at the end of February 2012, after legal action by the City Corporation.

Ministry

St Paul’s Cathedral is a busy church with three or four services every day, including Matins, Eucharist and Evening Prayer or Evensong. In addition, the Cathedral has many special services associated with the City of London, its corporation, guilds and institutions. The cathedral, as the largest church in London, also has a role in many state functions such as the service celebrating the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II. The cathedral is generally open daily to tourists, and has a regular program of organ recitals and other performances. The Bishop of London is The Right Reverend Richard Chartres who was installed in January 1996.

St. Paul’s during a special service in 2008 Dean and Chapter

St. Paul’s during a special service in 2008 Dean and Chapter

The Chapter comprises the Dean and four Residentiary Canons, each with a different responsibility in the running of the cathedral.

- Dean – The Very Revd Dr David Ison (since 25 May 2012)

- Pastor – The Rt Revd Michael Colclough (since 20 April 2008) is responsible for the pastoral needs of the staff and all visitors to the cathedral.

- Chancellor – The Revd Canon Mark Oakley (since 11 January 2013). Previously Treasurer of St Paul’s, Canon Oakley is in charge of the cathedral’s educational outreach to schools and the public.

- Precentor – The Revd Canon Michael Hampel (since 25 March 2011), is responsible for music at the cathedral.

- Treasurer – Revd Preb Philippa Boardman (May 2013) is responsible for finance and for the cathedral building.

College of Minor Canons There are three Minor Canons who co-ordinate many aspects of the daily running of the cathedral, conducting services, arranging liturgy and music, acting as chaplain, and facilitating the needs of visitors and school groups.

- Sacrist – The Revd Jason Rendell (since June 2007), has been appointed as Chaplain to the Bishop of Chichester (June 2013).

- Chaplain – The Revd Sarah Eynstone (since 12 January 2010 installation)

- Succentor – The Revd Jonathan Coore (since 19 September 2012 installation)

Music – List of musicians at English cathedrals

Organ

The organ was commissioned from Bernard Smith in 1694. The current instrument is the third-largest in Great Britain in terms of number of pipes (7,266), with 5 manuals, 189 ranks of pipes and 108 stops, enclosed in an impressive case designed in Wren’s workshop and decorated by Grinling Gibbons.

The organ was commissioned from Bernard Smith in 1694. The current instrument is the third-largest in Great Britain in terms of number of pipes (7,266), with 5 manuals, 189 ranks of pipes and 108 stops, enclosed in an impressive case designed in Wren’s workshop and decorated by Grinling Gibbons.

Details of the organ from the National Pipe Organ Register

Choir

St Paul’s Cathedral has a choir of men and boys to sing regularly at services. The earliest records of the choir date from 1127. The present choir consist of thirty boy choristers, eight probationers, and the Vicars Choral of twelve men who are professional singers. During school terms the choir sings at Evensong six times per week, the service on Thursdays being sung by the Vicars Choral without the boys. On Sundays the choir also sings at Matins and Eucharist. Many distinguished musicians have been organists, choir masters and choristers at St Pauls Cathedral including the composers John Redford, Thomas Morley, John Blow, Jeremiah Clarke and John Stainer, while well known performers have included Alfred Deller, John Shirley-Quirk, Anthony Way and the conductors Charles Groves and Paul Hillier, and the poet Walter de la Mare.