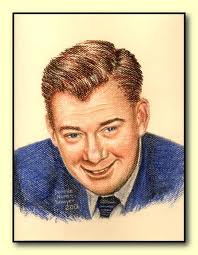

Arthur Godfrey

Arthur Godfrey and Friends

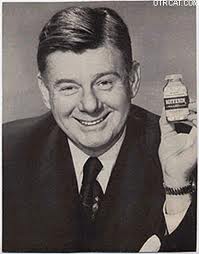

Godfrey spoke directly to his listeners as individuals; he was a foremost pitchman into the TV era

Arthur Morton Godfrey (born August 31, 1903 – died March 16, 1983) was an American radio and television broadcaster and entertainer who was sometimes introduced by his nickname, The Old Redhead. No television personality of the 1950s enjoyed more clout or fame than Godfrey until a famous on-the-air incident undermined his folksy image and triggered a gradual decline; the then-ubiquitous Godfrey helmed two CBS-TV weekly series and a daily 90-minute television mid-morning show through most of the decade, but by the early 1960s found himself reduced to hosting an occasional TV special.

Arguably the most prominent of the medium’s early master commercial pitchmen, he was strongly identified with many of his many sponsors, especially Chesterfield cigarettes and Lipton Tea. After many years of advertising for Chesterfield (during which Godfrey came up with the idea and slogan “Buy ’em by the carton”), he severed the relationship during one of his television programs, when his doctors convinced him that his lung cancer was due to smoking. Subsequently, he became a prominent spokesman for anti-smoking education.

Early life

Godfrey was born in New York City in 1903. His mother, Kathryn Morton Godfrey, was from a well-to-do Oswego, New York, family which disapproved of her marriage to an older Englishman, Arthur Hanbury Godfrey. The senior Godfrey was a sportswriter and considered an expert on surrey and hackney horses, but the advent of the automobile devastated the family’s finances. By 1915, when Arthur was 12, the family had moved to Hasbrouck Heights, New Jersey. Arthur, the eldest of five children, tried to help them survive by working before and after school, but at age 14 left home to ease the financial burden on the family. By 15 he was a civilian typist at Camp Merritt, New Jersey, and enlisted in the Navy (by lying about his age) two years later.

Arthur Godfrey

Godfrey’s father was something of a “free thinker” by the standards of the era. He did not disdain organized religion but insisted that his children explore all faiths before deciding for themselves which to embrace. Their childhood friends included Catholic, Jewish and every kind of Protestant playmates. The senior Godfrey was friends with the Vanderbilts, but was as likely to spend his time talking with the shoeshine man or the hotdog vendor about issues of the day. In the book, Genius in the Family (G.P. Putnam’s Sons, New York, 1962), written about their mother by Godfrey’s youngest sister, Dorothy Gene (who preferred to be called “Jean”), with the help of their sister, Kathy, it was reported that the angriest they ever saw their father was when a man on the ferry declared the Ku Klux Klan a civic organization vital to the good of the community. They rode the ferry back and forth three times, with their father arguing with the man that the Klan was a bunch of “Blasted, bigoted fools, led ’round by the nose!”

Godfrey’s mother, Kathryn, was a gifted artist and composer whose aspirations to fame were laid aside to take care of her family after her husband, Arthur or “Darl,'” died. Her creativity enabled the family to get through some very hard times by playing the piano to accompany silent movies, making jams and jellies and crocheting bedspreads to sell, and even cutting off and selling her floor length hair, as it was extremely difficult for a woman of her “class” to find work without violating social mores of the time. The one household item that was never sold or turned into firewood was the piano, and she believed at least some of her children would succeed in show business. In her later years some of her compositions were performed by symphony orchestras in Canada, which earned her a mention in Time. In 1957, at the age of 78, her sauciness made her a big hit with the audience when she appeared on Groucho Marx‘s quiz show You Bet Your Life. She died of cancer in 1968 at a nursing home in a suburb north of Chicago.

Godfrey served in the United States Navy from 1920 to 1924 as a radio operator on naval destroyers, but returned home to care for the family after his father’s death. Additional radio training came during Godfrey’s service in the Coast Guard from 1927 to 1930. He passed a very stringent qualifying examination and was admitted to the prestigious Radio Materiel School at the Naval Research Laboratory, graduating in 1929. It was during a Coast Guard stint in Baltimore that he appeared on a local talent show and became popular enough to land his own brief weekly program.

Radio

In this CBS publicity photo of Arthur Godfrey Time, vocalist Patti Clayton is seen at the far right and Godfrey sits in the foreground. Clayton, the original 1944 voice of Chiquita Banana, was married to Godfrey’s director, Saul Ochs.

On leaving the Coast Guard, Godfrey became a radio announcer for the Baltimore station WFBR (now WJZ (AM)) and moved the short distance to Washington, D.C. to become a staff announcer for NBC-owned station WRC the same year and remained there until 1934.

Recovering from a near-fatal automobile accident en route to a flying lesson in 1931 (by which time he was already an avid flyer), he decided to listen closely to the radio and realized that the stiff, formal style then used by announcers could not connect with the average radio listener; the announcers spoke in stentorian tones, as if giving a formal speech to a crowd and not communicating on a personal level. Godfrey vowed that when he returned to the airwaves, he would affect a relaxed, informal style as if he were talking to just one person. He also used that style to do his own commercials and became a regional star.

Godfrey at the 1948 ceremony marking the 100th anniversary of the Washington Monument.

In addition to announcing, Godfrey sang and played the ukulele. In 1934 he became a freelance entertainer, but eventually based himself on a daily show titled Sundial on CBS-owned station WJSV (now WFED) in Washington. Godfrey was the station’s morning disc jockey, playing records, delivering commercials (often with tongue in cheek; a classic example had him referring to Bayer Aspirin as “bare ass prin”), interviewing guests, and even reading news reports during his three-hour shift. Godfrey loved to sing, and would frequently sing random verses during the “talk” portions of his program. In 1937, he was a host on Professor Quiz, radio’s first successful quiz program. One surviving broadcast from 1939 has Godfrey unexpectedly turning on his microphone to harmonize with The Foursome’s recording of “There’ll Be Some Changes Made.”

He knew President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who listened to his Washington program, and through Roosevelt’s intercession, he received a commission in the U.S. Naval Reserve before World War II. Godfrey eventually moved his base to the CBS station in New York City, then known as WABC (now WCBS), and was heard on both WJSV and WABC for a time. In the autumn of 1942, he also became the announcer for Fred Allen‘s Texaco Star Theater show on the CBS network, but a personality conflict between Allen and Godfrey led to his early release from the show after only six weeks.

Godfrey became nationally known in April 1945 when, as CBS’s morning-radio man in Washington, he took the microphone for a live, firsthand account of President Roosevelt’s funeral procession. The entire CBS network picked up the broadcast, later preserved in the Edward R. Murrow and Fred W. Friendly record series, I Can Hear it Now. Unlike the tight-lipped news reporters and commentators of the day, who delivered breaking stories in an earnest, businesslike manner, Arthur Godfrey’s tone was sympathetic and neighborly, lending immediacy and intimacy to his words. When describing new President Harry S. Truman‘s car in the procession, Godfrey fervently said, in a choked voice, “God bless him, President Truman.” Godfrey broke down in tears and cued the listeners back to the studio. The entire nation was moved by his emotional outburst.

Godfrey made such an impression on the air that CBS gave him his own morning time slot on the nationwide network. Arthur Godfrey Time was a Monday-Friday show that featured his monologues, interviews with various stars, music from his own in-house combo and regular vocalists. Godfrey’s monologues and discussions were usually unscripted, and went wherever he chose.” Arthur Godfrey Time” remained a late morning staple on the CBS Radio Network schedule until 1972.

However, two pre-written radio monologs proved to be audience favorites and were rebroadcast on several occasions by popular demand, and again later on his television show. They were “What is a Boy?” and a follow-up, “What is a Girl?” With the skilled addition of sentimental music, both monologs captured very well the essence of what made parents love their children, fondly describing the highly varied personality traits of each child as the monolog progressed. Each monolog struck a heartfelt chord with everyone who heard it. “What is a boy?” in particular proved to be so popular that it was released as one of Godfrey’s records, which he issued on Columbia Records (Record no. 39487) in the summer of 1951, with “What is a Girl?” on the b-side of the record. It peaked on the billboard charts in August 1951, one of several successful records Godfrey released between 1947 and 1952.

In 1947, Godfrey had a surprise hit record with the novelty “Too Fat Polka (She’s Too Fat For Me)” written by Ross MacLean and Arthur Richardson. The song’s popularity led to the Andrews Sisters recording a version adapted to the women’s point-of-view.

Publicity still with Bing Crosby and Perry Como in 1950 for Crosby’s radio show.

Godfrey’s morning show was supplemented by a primetime variety show, Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts, broadcasting from the CBS Studio Building at 49 East 52nd Street where he had his main office. This variety show, a showcase for rising young performers, was a slight variation of CBS’s successful Original Amateur Hour. Some of the performers had made public appearances in their home towns and were recommended to Godfrey by friends or colleagues. These “sponsors” would accompany the performers to the broadcast and introduce them to Godfrey on the air. Two acts from the same 1948 broadcast were Wally Cox and The Chordettes. Both were big hits that night, and both were signed to recording contracts. Godfrey took special interest in The Chordettes, who sang his kind of barbershop-quartet harmony, and he soon made them part of his broadcasting and recording “family.”

Performers who appeared on Talent Scouts included Lenny Bruce, Don Adams, Tony Bennett, Patsy Cline, Pat Boone, opera singer Marilyn Horne, Roy Clark, and Irish vocalist Carmel Quinn. Later, he promoted “Little Godfrey” Janette Davis to a management position as the show’s talent coordinator. Three notable acts rejected for the show were Elvis Presley, Sonny Till & The Orioles, and The Four Freshmen. Following his appearances on the Louisiana Hayride, Presley traveled to New York for an unsuccessful Talent Scouts audition in April 1955; after the Talent Scouts staff rejected The Orioles, they went on to have a hit record with “Crying in the Chapel” and kicked off the “bird group” trend of early rock ‘n’ roll.

Godfrey was also an avid amateur radio operator, with the station call sign K4LIB. He was a member of the National Association of Broadcasters Hall of Fame in the radio division.

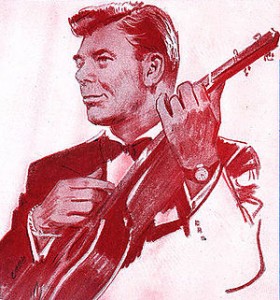

Television – 1953 portrait of Godfrey with ukulele

In 1948 Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts began to be simultaneously broadcast on radio and television, and by 1952, Arthur Godfrey Time also appeared on both media. The radio version ran an hour and a half; the TV version an hour, later expanded to an hour and a half. The Friday shows, however, were heard on radio only, because at the end of the week, Godfrey traditionally broadcast his portion from a studio at his Virginia farm outside of Washington, D.C., and TV cameras were unable to transmit live pictures of him and his New York cast at the same time. Godfrey’s skills as a commercial pitchman brought him a large number of loyal sponsors, including Lipton Tea, Frigidaire, Pillsbury cake mixes and Liggett & Myers‘s Chesterfield cigarettes.

He found that one way to enhance his pitches was to extemporize his commercials, poking fun at the sponsors (while never showing disrespect for the products themselves), the sponsors’ company executives, and advertising agency types who wrote the scripted commercials that he regularly ignored. (If he read them at all, he ridiculed them.) To the surprise of the advertising agencies and sponsors, Godfrey’s kidding of the commercials and products frequently enhanced the sales of those products. His popularity and ability to sell brought a windfall to CBS, accounting for a significant percentage of their corporate profits.

In 1949 Arthur Godfrey and His Friends, a weekly informal variety show, began on CBS-TV in prime time. His affable personality combined warmth, heart, and occasional bits of double entendre repartee, such as his remark when the show went on location: “Well, here we are in Miami Bitch. Hehheh.” Godfrey received adulation from fans who felt that despite his considerable wealth, he was really “one of them,” his personality that of a friendly next-door-neighbor. His ability to sell products, insisting he would not promote any in which he did not personally believe, gave him a level of trust from his audience, a belief that “if Godfrey said it, it must be so.” When he quit smoking after his 1953 hip surgery, he began speaking out against smoking on the air, to the displeasure of longtime sponsor Chesterfield. When he stood his ground, the company withdrew as a sponsor. Godfrey shrugged off their departure since he knew other sponsors would easily fill the vacancy.

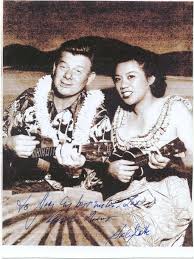

Eventually Godfrey added a weekend “best of” program culled from the week’s Arthur Godfrey Time, known as Arthur Godfrey Digest. He began to veer away from interviewing stars in favor of a small group of regular performers that became known as the “Little Godfreys.” Many of these artists were relatively obscure, but were given colossal national exposure, some of them formerTalent Scouts winners including Hawaiian vocalist Haleloke, veteran Irish tenor Frank Parker, Marian Marlowe and Julius LaRosa, who was in the Navy when Godfrey, doing his annual Naval reserve duty, discovered the young singer and offered him a job upon his discharge.

LaRosa joined the cast in 1951 and became a favorite with Godfrey’s immense audience, who also saw him on the prime-time weekly show Arthur Godfrey and his Friends. Godfrey also had a regular announcer-foil on the show: Tony Marvin. Godfrey preferred his performers not to use personal managers or agents, but often had his staff represent the artists if they were doing personal appearances.

Godfrey was one of the busiest men in the entertainment industry, often presiding over several daytime and evening radio and TV shows simultaneously. (Even busier was Robert Q. Lewis, who hosted Arthur Godfrey Time whenever Godfrey was absent, adding to his own crowded schedule.) Both Godfrey and Lewis made commercial recordings for Columbia Records, often featuring the “Little Godfreys” in various combinations. In addition to the “Too Fat Polka” mentioned above, these included “Candy and Cake”; “Dance Me Loose.” “I’m Looking Over a Four Leaf Clover;” “Slap ‘Er Down Again, Paw;” “Slow Poke“; and “The Thing“. In 1951 Godfrey also narrated a nostalgic movie documentary, Fifty Years Before Your Eyes, produced for Warner Brothers by silent-film anthologist Robert Youngson.

On a memorable evening in 1953, disc jockey Steve Allen was a last-minute replacement for Godfrey on Talent Scouts. When it came time to deliver the live commercial for Lipton tea and soups, Allen impulsively prepared the soup and the tea on camera, and poured both into a ukulele. Shaking the mixture well, he played a few damp notes while reciting the rest of the commercial, to the delight of the studio audience, the viewers, and Godfrey himself. Allen became a national celebrity and within the year he would become the first host of NBC’s Tonight Show.

Godfrey had been in pain since the 1931 car crash that damaged his hip. In 1953, he underwent pioneering hip replacement surgery in Boston using an early plastic artificial hip joint. The operation was successful and he returned to the show to the delight of his vast audience. During his recovery, CBS was so concerned about losing Godfrey’s audience that they encouraged him to broadcast live from his Beacon Hill estate (near Leesburg, Virginia), with the signal carried by microwave towers built on the property.

In his own way, Godfrey was a social pioneer. One of the “Little Godfrey” acts were the Mariners, an integrated vocal quartet of white and black Coast Guard veterans. When the act appeared on his TV show, Southern CBS affiliates and racist Southern politicians complained of their participating in dance sequences with white women and resented their presence on the show at all. Godfrey responded caustically, decrying the racism and refusing to remove them from the cast. At the time, CBS backed him.

Godfrey’s immense popularity and the trust placed in him by audiences was noticed by not just advertisers but also his friend U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower, who asked him to record a number of public service announcements to be played on American television in the case of nuclear war. It was thought that viewers would be reassured by Godfrey’s grandfatherly tone and folksy manner. The existence of the PSA tapes was confirmed in 2004 by former CBS president Dr. Frank Stanton in an exchange with a writer with the Web site CONELRAD.

Aviation

Godfrey (left) with NACA pilot George Cooper and Ames Director Smith DeFrance

Godfrey learned to fly in the 1930s while working in broadcast radio in the Washington, D.C., area, starting out with gliders, then learning to fly airplanes. He was badly injured on his way to a flying lesson one afternoon in 1931 when a truck, coming the other way, lost its left front wheel and hit him head on. Godfrey spent months recuperating, and the injury would keep him from flying on active duty during World War II. He served as a reserve officer in the United States Navy in a public affairs role during the war.

Godfrey used his pervasive fame to advocate a strong anti-Communist stance and to pitch for enhanced strategic air power in the Cold War atmosphere. In addition to his advocacy for civil rights, he became a strong promoter of his middle-class fans vacationing in Hawaii and Miami Beach, Florida, formerly enclaves for the wealthy. He made a television movie in 1953, taking the controls of an Eastern Airlines Lockheed Constellation airliner and flying to Miami, thus showing how safe airline travel had become. As a reserve officer, he used his public position to cajole the Navy into qualifying him as a Naval Aviator, and played that against the United States Air Force, who successfully recruited him into the Air Force Reserve. At one time during the 1950s, Godfrey had flown every active aircraft in the military inventory.

His continued unpaid promotion of Eastern Airlines earned him the undying gratitude of good friend Eddie Rickenbacker, the World War I flying ace who was the President of the airline. He was such a good friend of the airline that Rickenbacker took a retiring Douglas DC-3, fitted it out with an executive interior and DC-4 engines, and presented it to Godfrey, who then used it to commute to the studios in New York City from his huge Leesburg, Virginia, farm every Sunday night.

Later life

In 1959, Godfrey began suffering chest pains. Closer examination by physicians revealed a mass in his chest that could possibly have been lung cancer. Later that same year, Godfrey ended Arthur Godfrey Time and The Arthur Godfrey Show (as the prime-time series was known after the fall of 1956) after revealing his illness.

Surgeons discovered cancer in one lung that spread to his aorta. One lung was removed. Yet, despite the disease’s discouragingly high mortality in that era, it became clear after radiation treatments that Godfrey had beaten the substantial odds against him. He returned to the air on a prime-time special and resumed the daily morning show on radio, reverting to a format featuring guest stars such as ragtime pianist Max Morath and Irish vocalist Carmel Quinn, maintaining a live combo of first-rate Manhattan musicians (under the direction of Sy Mann) as he had done since the beginning. Longtime announcer Tony Marvin, with Godfrey since the late 1940s, did not make the transition to the new program. Marvin was one of the few Godfrey associates who left Godfrey on amicable terms, and went on to a career as a news anchor on the Mutual Broadcasting Network. The Godfrey show was the last daily longform entertainment program on American network radio when Godfrey and CBS agreed to end it in April 1972, when his 20-year contract with the network expired. Godfrey by then was a colonel in the United States Air Force Reserve and still an active pilot.

He appeared in the movies 4 for Texas (1963), The Glass Bottom Boat (1966), and Where Angels Go, Trouble Follows (1968). He briefly co-hosted Candid Camera with creator Allen Funt, but that relationship, like so many others, ended acrimoniously; Godfrey hosted at least one broadcast without Funt. Godfrey also made various guest appearances, and he and Lucille Ball co-hosted the CBS special 50 Years of Television (1978). He also made a cameo appearance in the 1979 B-movie Angel’s Revenge.

The Arthur Godfrey Collection

Toward the end of his life, Godfrey became a major supporter of public broadcasting, and left his large personal archive of papers and programs to public station WNET/Thirteen in New York. Godfrey biographer Art Singer helped to arrange a permanent home for the Godfrey material at the Broadcasting Archives at the University of Maryland in early 1998. The collection contains hundreds of kinescopes of Godfrey television programs, more than 4,000 audiotapes and wire recordings of his various radio shows, videotapes, and transcription discs. The collection also contains Godfrey’s voluminous personal papers and business records, which cover his spectacular rise and precipitous fall in the industry over a period of more than 50 years.

Death

Emphysema, thought to have been caused by decades of smoking and the radiation treatments for Godfrey’s lung cancer, became a problem in the early 1980s. He died of the condition in New York City on March 16, 1983. Godfrey was buried at Union Cemetery in Leesburg, Virginia, not far from his farm in Waterford, Virginia.

Personal life

Godfrey was married twice. He and his first wife, Catherine, had one child. He was then married to the former Mary Bourke from 1938 until their divorce in 1982, a year before his death. They had three children. His granddaughter is Mary Schmidt Amons, a cast member on The Real Housewives of Washington, D.C..

Godfrey was an avid equestrian; he was considered a master at dressage and showed his horses on the American horse show circuit. He was also an aviator.